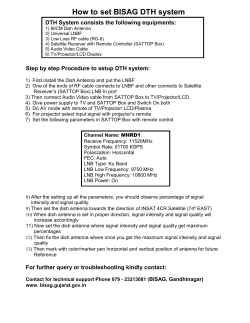

CNet how to sell yourself