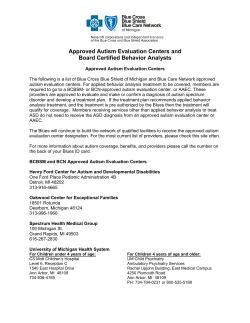

A Needs Assessment of Parents on How to