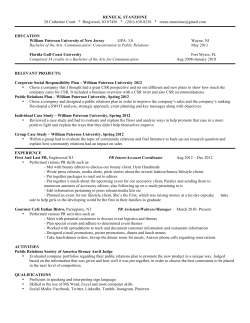

Document 237988