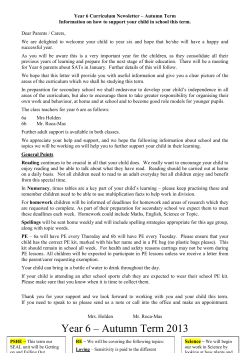

Document 240564