Know What Works and Why English Edition, October 2013

Know What Works and Why English Edition, October 2013 ENG 2 0 Academic journal about the benefits and impact of ICT in education 1 3 Publication details Know What Works and Why is an editorially independent Dutch journal about the benefits and impact of ICT in education. The print edition is published quarterly. Subscribe to this free Dutch journal Editors WWW: 4W.Kennisnet.nl Alfons ten Brummelhuis, Head of Research Department, Kennisnet Adress: 4W@Kennisnet.nl Melissa van Amerongen, Researcher, Kennisnet ©Kennisnet, Zoetermeer, the Netherlands English edition, October 2013 ISSN: 2213-8757 Sylvia Peters, Researcher, Kennisnet Text editing Jacqueline Kuijpers, MareCom Breda, the Netherlands Published by Anneleen Post, Meer dan Letters & Papier, Utrecht, the Kennisnet Foundation, Zoetermeer, the Netherlands Netherlands Kennisnet is the Dutch Expertise Center on ICT and Education Contributors to this issue Adriana G. Bus (Leiden University, the Netherlands), Hedderik van Rijn (University of Groningen, the Netherlands), Menno Nijboer (University of Groningen, the Netherlands), Ruben Vanderlinde (Ghent University, Belgium), Johan van Braak (Ghent University, Know What Works and Why English Edition, 2013 Illustrations Flos Vingerhoets Illustratie, Haarlem, the Netherlands Layout Tappan Communicatie, The Hague, the Netherlands Fabrique, Rotterdam, the Netherlands Belgium), Jolien Francken (Donders Institute for Brain, Cognition Translation and Behavior, Radboud University Nijmegen, the Netherlands), Balance Translations, Maastricht/Amsterdam, the Netherlands Jo Tondeur (Ghent University, Belgium), Natalie Pareja Roblin (Ghent University, Belgium), Petra Fisser (Institute for Curriculum Development, the Netherlands ), Joke Voogt (University of Twente, the Netherlands). Attribution – Non-commercial – No Derivatives 2.5 Nederland. The user may: • Copy, distribute, show, and openly implement the work subject to the following conditions: Attribution. The user must attribute the work to Kennisnet. Non-commercial. The user may only use the work for non-commercial purposes. No derivative works. The user may not create derivative work using the work. • When reusing or distributing the work, the user must notify third parties of the conditions of the license for this work. • The user may only waive one or more of these conditions with the prior permission of Kennisnet. The foregoing shall have no effect on the statutory restrictions on intellectual property rights. (www.creativecommons.org/licenses) This is a publication of the Kennisnet Foundation. Academic journal about the benefits and impact of ICT in education Contents 1. Using ICT to optimize the memorization of facts Hedderik van Rijn & Menno Nijboer Editorial 6 The journal Know What Works and Why [Dutch title: 4W, Weten Wat Werkt en Waarom] addresses the benefits and impact of ICT in education. 2. Educational software for young children Adriana G. Bus 14 3. What makes an ICT policy plan so effective? Ruben Vanderlinde & Johan van Braak 22 The Netherlands has a relatively solid basis for using ICT in education. Virtually all schools have high-speed Internet access, many pupils have access to computers, most schools are equipped with interactive whiteboards, etc. Despite this, the use of ICT is lagging behind teachers’ and principals’ expectations and ambitions, and opportunities are not being utilized to their full potential. Teachers indicate that they find it difficult to fully embed ICT into their lessons. They are critical and first want to know how much value ICT will add to their teaching and when. 4. Handwriting versus typing: What does neuroscience have to say? Jolien C. Francken 30 5. Practical examples as a resource for professional development Jo Tondeur, Natalie Pareja Roblin, Johan van Braak, Petra Fisser & Joke Voogt 38 We are convinced that scientific insights can be helpful when making professional choices regarding the use of ICT in education. Unfortunately, scientific articles are not readily accessible to teachers and are not written for the purpose of providing them with professional support. In publishing 4W, a journal intended for researchers but also for teachers, pre-service teachers, and principals, we make the results of research available in order to give them the professional support they need. The philosophy underlying the journal is that teachers need to know not only what works, but why it works. Teachers who have a thorough understanding of what makes a particular application work can make better decisions about what type of ICT can help them achieve their goals and when. We take a broad view of ICT, covering its use for didactic, organizational, and professional development purposes. The articles we publish are written by experts in the relevant field and are reviewed externally when necessary. They are accompanied by a limited selection of peer-reviewed reference articles. The journal is published quarterly both in print and online. This English-language edition is meant to introduce the journal to an international audience. We would be delighted to have you contact the editorial staff if you would like to contribute an article. Alfons ten Brummelhuis Sylvia Peters Melissa van Amerongen Editors 4W | 4w.kennisnet.nl 4 5 1 Using ICT to optimize the memorization of facts Hedderik van Rijn and Menno Nijboer University of Groningen Facts are best learned by constantly repeating them in a way that allows for the facts you already know and the ones you do not. Thanks to computer programs based on human memory models, this customized learning method can now be supplied by computers. The result: impressive Knowledge that has been passively acquired is not retained as well as information that has been actively retrieved from memory improvements in learning performance. It is impossible to appreciate the beauty of Rilke’s ming. ‘Cramming’ is repeating the material to be poetry unless one has studied German. It is learned as often as possible, often on the day, or impossible to understand many historical trends even in the hours, before an exam. Cramming unless one knows the years in which significant often consists of nothing more than reading and events occurred. It is impossible to place articles re-reading lines of words to be learned. The long- from quality newspapers in context unless one term inefficiency of this method, however, has knows the names of capital cities. been recognized for over a century: the person Although few students are fond of doing so, studying may retain the knowledge for the dura- learning a basic amount of factual knowledge is tion of the exam, but it is quickly forgotten once inevitable and often simply comes down to cram- the exam is over (Ebbinghaus, 1885). 6 Know What Works and Why • 4W • English Edition, October 2013 7 excellent moderate poor Level of activation/knowledge excellent Figure 1: More widely spaced learning (the dotted line) results in better mastery of a fact than closely spaced repetition One of the reasons that re-reading is so ineffec- (Pashler, et al., 2007). moderate Time Figure 2: Individual differences mean that an easy fact (the solid line) requires only two repetitions to be mastered at the same level as a difficult fact (the dotted line), which requires six such repetitions. not more frequently applied in a classroom setting acquired is not retained as well as information that Learning methods has been actively retrieved from memory. This Over the years, however, a variety of learning testing effect results from the fact that actively systems have been developed to facilitate the retrieved information is stored more securely in use of the spacing and testing effects, including our memories, which means that, as a learning the Leitner system and the Pimsleur method. The method, a quiz or test is much more effective Pimsleur method involves repeating the informa- preparation for an exam than re-reading the mate- tion at intervals that gradually become longer. This rial to be learned. method encompasses both the spacing and test- The spacing effect also positively influences ing effects, but the intervals between repetitions knowledge retention. As many people know from are not tailored to individual learners – the system experience, it is better to spread the job of learn- is based on a supposed average learner. ing something out over several days rather than While the Pimsleur method is the same for cramming everything in the evening before an everyone, the Leitner system is governed entirely exam. But this effect demonstrates benefits even by the learner’s answers. Although this method within a single learning session: it is better to learn meets most of the criteria for optimal learning, a fact by spacing out repetitions rather than to it does not respond well to ‘tentative’ answers – memorize the same fact again and again without what if the learner knows the answer but gives it a break. five minutes’ thought before providing it? Pupils who help each other learn facts, and poor Level of activation/knowledge apply in the absence of a tester and why they are tive is that knowledge that has been passively Time 8 The spacing effect and the testing effect parents who help their children do so, often use Memory models the testing method. Although the learner may Fortunately, modern theories of human memory not realize it, the testing effect results in better can help us develop an optimal method for learn- knowledge retention. Moreover a good tester will ing facts (Pavlik & Anderson, 2005; Taatgen, automatically take the spacing effect into account, 2009). According to these theories, the knowledge repeating questions that cause the learner to level of each fact can be expressed as a figure hesitate or stumble more frequently than those indicating how ‘active’ that fact is in our memory. for which the learner has a ready answer. A good This is determined by the number of earlier prac- tester thus fulfills the two most important criteria tice sessions and the dates/times when the fact for learning facts successfully: the spacing effect was practiced. Figure 1 illustrates two different and the testing effect. situations: the solid line indicates the activation It will be clear to the reader that this method of a ‘crammed’ fact that was practiced four times only works when the facts are presented in a way in closely spaced sessions, while the dotted line that is tailored to the learner’s abilities. This is one represents a fact that was practiced the same of the reasons that these principles are difficult to number of times but in more widely spaced ses9 sions. The peaks indicate the times of the practice tween easy facts and difficult ones. The model Because it is tailored to the individual learner, this This paper originally appeared in Dutch in 4W sessions. As the graph shows, activation declines can then be used to predict how mastery of optimized learning method is also highly motiva 2012(1) as Optimaal feiten leren met ict (pp. 6-11). rapidly after a practice session, but the decline these facts will decline over the course of time. ting for them. Translation: Balance Translation, Maastricht. becomes less sharp over time. The most interesting observation from a learning perspective is that ICT-supported learning the ‘crammed’ fact is more active after the last The ideas described above can be applied in a time it is presented, but that it is forgotten more learning-optimization system comprising a com- quickly, showing that presenting facts over widely puter simulation of human memory function that Hedderik van Rijn Menno Nijboer spaced sessions ultimately leads to a higher level can estimate how well each fact is mastered at any Main author Author of knowledge. This is because the speed at which given time. This system would present facts that hedderik@van-rijn.org a fact is forgotten depends on how active the fact have a low level of activation at the moment they was when it was presented again. When pres- are learned. Repetition will prevent these facts from entations are spaced, activation is lower when being forgotten and, because the fact will have a the new presentation is made, which means less low level of activation, that repetition will be very Hedderik van Rijn is an Associate Professor Menno Nijboer is part of the Artificial Intel- forgetting. Spaced presentations therefore result effective. In this way, the system smoothly imple- of Cognitive Psychology at the University of ligence Department and is working on a dis- in better knowledge retention. ments the principles of both spacing and testing: Groningen, where he is involved in the Artificial sertation on optimal multitasking. His graduate The model illustrated in Figure 1 is based on difficult facts are quickly forgotten and so they Intelligence and Computational Neuroscience research has demonstrated that the Clever an idealized situation in which all facts are forgot- are repeated more often. Easy facts elicit quick programs. His work focuses on the role time Cramming method delivers the best results if ten at the same rate. A more realistic situation is responses and are therefore repeated less often. plays in cognition, such as the best time for information is repeated multiple times. illustrated in Figure 2, with one easy fact (the solid In recent years, students at the University of offering information to be learned. line) and one difficult fact (the dotted line). As this Groningen have used and tested this system figure shows, the difficult fact will have to be re- extensively at secondary schools and in the first peated six times before achieving the same level few years of university courses. This optimized of mastery as the easy fact. This is exactly why method produced final grades that in some cases human testers are so effective – they can easily were more than a full point higher in comparison anticipate and meet this need. with ordinary ‘cramming’ or various forms of ‘im- According to this type of memory model, the proved cramming’ (Van Rijn, 2010). activation of a fact is linked directly to the time This method has been improved and tested in it takes to retrieve that fact: a fact that has a the Kennisnet Clever Cramming projects involving very low level of activation will be more difficult lessons in Dutch as a second language. Clever and thus take longer to retrieve, if it has not Cramming has proved to be an ideal system in already been forgotten. This means that the these lessons: because the system automati- time it takes to give an answer can be a factor cally adapts to the learner’s level, it can be used in assessing how well someone knows a certain with equal success with students with extremely fact. Based on this, internal activation can be limited language skills and students who have adjusted so that the model distinguishes be- completed advanced degrees. 10 11 What we know about ICT-based memorization Want to know more? Ebbinghaus, H. (1885). Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology. Teachers College, Columbia University, translated by Henry A. Ruger and Clara E. Bussenius (1913). Available at: http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Ebbinghaus/ ● In order to optimize learning, the learning schedule must be tailored index.htm. to the individual learner’s knowledge and ability. The learning method must also take into account the spacing effect (breaks Pashler, H., Bain, P., Bottge, B. , Graesser, A., Koedinger, K., McDaniel, M., between learning sessions) and the testing effect (active retrieval of and Metcalfe, J. (2007). Organizing Instruction and Study to Improve Student facts through testing results in better retention). Learning (NCER 2007-2004). Washington, D.C.: National Center for Education Research, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. ● Thanks to computer programs based on human memory models, this customized learning method can now be supplied by computers. Pavlik, P. I. and Anderson, J. R. (2005). Practice and forgetting effects on vocabulary memory: An activation-based model of the spacing effect. Cognitive ● These computer models’ capacity for adaptation provides students Science, 29(4), 559-586. with a learning program tailored to their individual learning capacity. This improves both learning results and learner motivation. Taatgen, N.A. (2009). Kennisopslag, vergeten en geheugen (English: Knowledge storage, forgetting, and memory). In R. Klarus and R.J. Simons (Eds.), Wat is goed onderwijs? Bijdragen uit de psychologie (English: What is good education? Contributions from psychology) (pp. 33-46). The Hague: Lemma. Van Rijn, H. (2010). SlimStampen. Optimaal leren door kalibratie op kennis en vaardigheid (English: Clever Cramming. Optimal learning by calibration according to knowledge and skills). http://onderzoek.kennisnet.nl/onderzoeken-totaal/ slimstampen. 12 13 2 Educational software for young children Adriana G. Bus Leiden University The number of educational computer programs available for pre-schoolers and kindergartners is growing exponentially. But do children learn from them? More than a decade of research is providing increasingly clear evidence of which programs can teach young children. The mid-90s saw the emergence of ‘edutain- language and reading skills, but also games that ment’: computer programs that combined educa- promote alphabetic knowledge (Living Letters) tion and entertainment and allowed children to and numeracy (Number Race). learn while they played. It was quite a revelation getting to know Just Grandma and Me, Kid Pix, Three vital principles Dr. Brain, and other fascinating programs that The question, of course, was and is whether became available at the dawn of educational children actually learn from these programs. software (Ito, 2009). Since then, an enormous The initial euphoria about the educational pos- number of educational software programs have sibilities these programs offered was quickly been launched. These include not only picture tempered when results lagged behind expec book apps that stimulate the development of tations (De Jong and Bus, 2002). But was that 14 Know What Works and Why • 4W • English Edition, October 2013 15 assessment correct? As experiments continue, it (“the bear is blushing, he is shy”). Multiple choice is becoming increasingly clear that edutainment questions are even more effective (“Where is the offers unique possibilities. The programs can even bear shy?”), with the child being offered three transform at-risk children into high performers images and choosing the one that best illustrates (Kegel, 2011 and Van der Kooy-Hofland, 2011). ‘shy’. ‘Making meaning’ works better than “taking What kinds of programs produce such results? meaning”. Experimental studies have revealed three vital Many parents do not like the fact that interac- features edutainment programs must have for tive computer programs make it impossible for children to benefit from them without teacher as- them to contribute. One frequent complaint heard sistance: interactivity, functionality, and feedback. about picture book apps is “As a parent you just 1. Interactivity In particular kindergarten children with a genetic predisposition for attention disorders benefit from the feedback of a computer tutor sit there and look at it”. A study by the Joan Ganz Cooney Center (2012) showed, predictably, that Interaction has long been considered an im- both parents and children become irritated when portant ingredient in adult-child book reading. parents attempt to read their child interactive Children get more out of being read to if the stories on an iPad, iPod, or laptop. adult intersperses questions about the story or For children aged three and older, picture book explains difficult words while reading. Electronic apps are just as effective as interactive reading picture books, sometimes referred to as nook (De Jong, 2003). For under-threes, however, it books (Barnes & Noble) or vooks (‘e-books’ is important that caregivers stress the words, with video), are also more effective when their images, and sounds that engage the child’s at- reading aloud is accompanied by questions or tention. The current generation of apps do not explanations (Smeets & Bus, 2012). Hotspots provide for such possibilities. The first app that are embedded in images so that clicking on them allows a choice of interactive moments has yet to or touching the screen provides the child with be released. an explanation of what he or she is looking at 16 17 2. Functionality in the computer group had heard the entire The fact that computer programs are better This paper originally appeared in Dutch in 4W A good balance between text and animation may story, and that child did not hear it in the correct than parents or teachers at providing consistent 2012(1) as Educatieve software voor jonge kin- increase learners’ arousal level (their interest in a order. Despite all of its possibilities, therefore, feedback may explain why they can also be more deren (pp. 12-17). Translation: Balance Translation, story), making it possible to read the same books this program never put the children in a reading effective than studying under teacher supervision Maastricht. more often to pupils and increase the intensity of mood. Earlier computer experience with games (Saine, et al., 2011). their reading experience. Research shows that significantly impacted the children’s approach to children are bored less quickly by living picture the new program (De Jong and Bus, 2002). books than by print books. Using skin resistance as an indicator, arousal drops sharply after 3. Adaptive performance feedback repeated readings of an ordinary print book, but Offering continuous performance feedback may Adriana Bus remains at a high level with a living book on the encourage children’s continued, positive engage- Author computer even after the book has been ‘read’ ment in computer programs. Although many bus@fsw.leidenuniv.nl four times (Verhallen & Bus, 2009). believe that computers are inferior to teachers But books may include too many attractive ani- in this area, computer programs that incorporate mations. Children sitting at a computer are quick a computer tutor may actually make substantial to adopt a game-playing attitude that causes contributions to the program’s effect (Kegel & Adriana Bus is a Professor of Education and educational goals to suffer. In particular, when kin- Bus, 2011). Child Studies at Leiden University, concentra dergartners are accustomed to using computers For example, one study has shown that a ting on emergent literacy. to play games, there is a good chance that they computer program is only effective (the effect in will overlook the story in the app in favor of seek- this case being a first step towards alphabetic ing out the more iconic elements of the program. knowledge) if the computer tutor continuously This became apparent during an experiment encourages children to respond, prompts them to involving electronic picture books that contained think carefully, gives them tips to arrive at the cor- a large number of hyperlinks. Each screen rect answer, and explains why their answer was presented the children with links that would correct. In particular kindergarten children with activate films in static illustrations or start an a genetic predisposition for attention disorders animation intended to clarify individual words. (about 35%) benefit from the feedback (Kegel, They could listen to the text being read aloud et al., 2011). They even learn significantly more and repeat it if desired. than their peers who are not predisposed to such The results? Most kindergartners immedi- disorders – an unexpected but understandable ately became playful, jumping randomly through result, since the increased sensitivity to stimuli the book looking for entertaining animated experienced by children with attention disorders features. The games were also a significant works to their advantage if the program’s conti draw, taking up approximately half of their al- nuous feedback keeps their approach to the lotted time. After playing with the hypertext for assignment on the right track. six 15-minute periods, only 1 of the 16 children 18 19 What we know about educational programs for young children Want to know more? Chiong, C., Ree, J., Takeuchi, L. & Erickson, I. (2012). Print Books vs. E-books. Comparing parent-child co-reading on print, basic, and enhanced e-book platforms. New York, NY: The Joan Ganz Cooney Center. Retrieved from http://www.joanganzcooneycenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/jgcc_ebooks_quickreport.pdf Picture book apps and other computer programs for young chil- Ito, M. (2009). Engineering play. A cultural history of children’s software. dren are livened up with countless multimedia additions. These can Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. increase computer activity effectiveness, provided that they possess three key features: De Jong, M.T. & Bus, A.G. (2002). Quality of book-reading matters for emergent readers: An experiment with the same book in a regular or electronic format. ● The first is interactivity. In this respect, making meaning is more Journal of Educational Psychology, 94, 145-155. effective than taking meaning. Kegel, C.A.T. & Bus, A.G. (2011). Feedback as a pivotal quality of a web-based ● The second is functionality. If a program contains too many ‘foreign’ elements, children will approach it as a game and will not engage in early literacy computer program. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104, 182192. Doi: 10.1037/a0025849. the activity for which the program is actually intended. Kegel, C.A.T., Bus, A.G. & Van IJzendoorn, M.H. (2011). Differential susceptibility ● The third is feedback. Continuous performance feedback helps children, and at-risk children in particular, work to their full potential. in early literacy instruction through computer games: The role of the Dopamine D4 Receptor Gene (DRD4). Mind, Brain, and Education, 5, 71-78. Saine, N.L., Lerkkanen, M.-J., Ahonen, T., Tolvanen, A. & Lyytinen, H. (2011). Computer-assisted remedial reading intervention for school beginners at risk for reading disability. Child Development, 82, 1013-1028. Smeets, D.J.H. & Bus, A.G. (2012). Interactive electronic storybooks for kindergartners to promote vocabulary growth. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 112, 36–55. Doi:10.1016/j. jecp.2011.12.003 Verhallen, M.J.A.J., and Bus, A.G. (2009). Video storybook reading as a remedy. Journal for Educational Research Online, 1, 11-19. Dissertations by De Jong (2003), Kegel (2011), Smeets (2012), Van der KooyHofland (2011), and Verhallen (2009) (https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/ handle/1887/9744/search). A demo version of ‘Living Letters’ [‘Letters in beweging’], an educational game for kindergartners that provides continuous performance feedback, can be found at 20 http://www.bereslim.nl/lettersinbeweging.htm (in Dutch). 21 3 What makes an ICT policy plan so effective? Cyclical process Interaction and cooperation ICT Coordinator 1. School’s vision of ‘good education’ 2. Overview of current ICT activities Comprehensive content 3. Set priorities Ruben Vanderlinde & Johan van Braak Ghent University 1. Vision development regarding ICT Teachers t 5. Prepare action plan 2. Financial aspects of ICT 4. Develop new ICT activities 3. ICT policy on infrastructure ICT can be used in schools in many different ways. The 4. ICT-related professional development policy question, of course, is when and how it can be used to yield 5. ICT’s role in the curriculum the best results. When school teams give this question their Teacher Teams considered thought, develop an ICT policy plan, and turn their ideas into reality, their school is bound to make more effective use of ICT. Developing an ICT policy plan in a team context is more important than simply having such a plan. School Principal Co or Te a m ICT researchers all over the world are work- are more successful at integrating ICT into their ing to identify the conditions that best support teaching and learning activities. the integration of ICT into school education. In their research, they generally make a distinction What is an ICT policy plan? between teacher-related conditions (e.g., compe- ICT policy plans can address issues at various tencies and ICT experience) and school-related levels. For example, national education authori- conditions (e.g., management and infrastructure). ties prepare ICT policy plans that present their One crucial school-related condition is to de- vision of ICT to schools and teachers. This article velop a school-based ICT policy plan. This article discusses the ICT policy plans formulated by discusses why schools with ICT policy plans schools themselves. According to the literature, 22 Know What Works and Why • 4W • English Edition, October 2013 in di na Local Community p vo tio n lve m Support aspects Electronic environments • pICTos omgevingen Elektronische • Four-inpICTos Balance en t Continuing education Data use Proces van Process of policy plan development ICT policy plan - Vier in Balans k Self-evaluation Result 23 school-based plans are documents defining the it more for educational purposes (Vanderlinde different school-related elements of ICT integra- & Van Braak, 2010). Obviously, successfully tion in education. These include a description of integrating ICT requires more from a school than the current use of ICT in education, as well as simply having an ICT policy plan on paper. The what the school wishes to achieve in this area. success enjoyed by schools with an ICT policy An ICT policy plan thus contains both strategic plan has more to do with the processes that elements (‘What are our ambitions as a school?’) precede the formulation of that plan. In order to and operational elements (‘Which steps should emphasize these processes, more and more re- be taken to achieve these ambitions?’). searchers are referring to the ‘school-based ICT Developed by the school, for the school Schools that develop an ICT policy plan use ICT more frequently during the school year and use it more for educational purposes al., 2012; Vanderlinde, Van Braak, et al., 2012), which stresses the underlying processes of an Published research shows that a school-based ICT policy plan. ICT policy plan is essential for the successful inte- Based on the various studies, we know that gration of ICT in education. This is the case in all there are a number of factors that can contribute sectors: primary and secondary education, as well to an ICT policy plan’s role as an impetus for as vocational training and higher education. The successful ICT integration in schools. schools that succeed in integrating ICT in their curricula are usually those that have developed a 1. Team involvement and coordination comprehensive ICT policy plan. Studies have also Successful schools involve the whole school identified a close link between ICT policy plans team in developing their ICT policy plans. An and both classroom innovation and changes to individual teacher or ICT coordinator will never pupils’ learning activities (Baylor & Ritchie, 2002). be able to develop an effective and efficient ICT Other researchers argue that ICT policy plans can policy plan on their own. The schools that use contribute to the sustainability of ICT as a specific ICT successfully are those whose ICT policy plan form of educational innovation (Jones, 2003). In is drawn up and developed by the entire school other words, an ICT policy plan can help schools team. All of the teachers are closely involved in incorporate ICT as a classroom innovation. the development process, and they are encour- The ICT policy plan: impetus for development 24 policy planning’ concept (Vanderlinde, Dexter, et aged to think about the plan’s content and to relate it to their classroom activities. In other words, the process of developing an ICT policy Our conclusion is that schools that develop an plan motivates the entire school team to think ICT policy plan are more successful than their about ICT’s place in the school and in the class- non-plan counterparts at integrating ICT, and that room. Research (Vanderlinde, Van Braak, et al., they develop better methods for doing so (Baylor 2012) shows, however, that this process must be & Ritchie, 2002). Not only do these schools led by a ‘visible’ coordinator, such as the school use ICT more frequently during the school year principal or the ICT coordinator. This person then (Tondeur, et al., 2008), but they also clearly use structures the policy plan development process 25 and monitors the progress made. depending on each school’s individual situation Ruben Vanderlinde Johan van Braak Author Research also shows that schools differ and context. Generally speaking, the ICT policy Main author significantly in the way they structure this process. plans of successful schools include five elements ruben.vanderlinde@ugent.be As a result, ICT policy plans can vary consider- (see Vanderlinde, Van Braak, et al., 2012): ably, depending on the situation of the individual • A vision of ICT’s place in education school. • An outline of ICT-related costs • An ICT policy relating to infrastructure 2. Cyclical process We know that working together on an ICT policy plan creates a certain dynamic within a school team (Vanderlinde, Van Braak, et al., 2012). An (hardware and software) • Policy concerning teachers’ development of their ICT skills • ICT’s role in the curriculum Ruben Vanderlinde works in the Department Johan van Braak also works in the Department of Educational Studies at Ghent University. He of Educational Studies Department at Ghent received his Ph.D. in 2011 for his dissertation University, where he researches ICT integra- on ICT policy planning in primary schools. tion in education. He was Ruben Vanderlinde’s supervising professor during the dissertation phase of Vanderlinde’s Ph.D. studies. effective ICT policy plan provides teachers with specific guidelines. It lets them know what is Because ICT policy plans can contain so many expected of them. This implies that an effective different elements, they give schools a powerful ICT policy plan is always a ‘work in progress’ tool in their efforts to integrate ICT successfully. (Fishman & Zhang, 2003). In other words, it is Moreover, an effective ICT policy plan contains not a one-time exercise, but a process that con- more than just specific guidelines for teachers tinuously changes and evolves. It is a long-term – it also addresses particular issues the school endeavor, and should be updated and amended faces as an organization. In other words, ICT at regular intervals, for example in order to inte- policy plans encompass elements touching on grate new technologies into the plan. both didactics and school management. 3. Starting from a clear vision of good education This paper originally appeared in Dutch in 4W The most successful ICT policy plans are those 2013(1) as Wat maakt een beleidsplan zo effec- that are grounded in a clear vision of the nature tief? (pp. 30-37). Translation: Balance Translation, of ‘good’ education that is supported by the staff Maastricht. (Fishman & Zhang, 2003; Vanderlinde & Van Braak, 2012). In other words, a school must first formulate its vision of ‘good’ education before considering the role of ICT in that context. When a school takes the time to develop that particular vision, it has a better chance of finding out how ICT can support teaching and learning in the classroom. 4. Comprehensive content As noted earlier, we know that school-based ICT policy plans can contain a variety of elements, 26 27 What we know about ICT policy plans Want to know more? Baylor, A.L. & Ritchie, D. (2002). What factors facilitate teacher skill, teacher morale, perceived student learning in technology-using classrooms? Computers & Education, 39, 395-414. ● Schools that successfully integrate ICT have an ICT policy plan that is developed and supported by the school’s entire staff. Schools with effective Fishman, B.J. & Zhang, B.H. (2003). Planning for technology: The link between ICT policy plans involve their teachers in the plan’s development and allow intentions and use. Educational Technology, 43, 14-18. teachers to determine its content. The plan offers teachers guidelines for integrating ICT into their teaching. Jones, R.M. (2003). Local and national ICT policies. In R.B. Kozma (Ed.), Technology, innovation and educational change: A global perspective (pp. 163- ● Effective ICT policy plans are always premised on the school’s vision of 194). Eugene, OR: International Society for Technology in Education. education. The school must define what it means by a ‘good education’ before exploring the role of ICT in that context. Tondeur, J., Van Keer, H., Van Braak, J. & Valcke, M. (2008). ICT integration in the classroom: Challenging the potential of a school policy. Computers & ● The process of developing an ICT policy plan is much more important Education, 51, 212-223. than merely having such a document. ICT policy plan development is a cyclical process, and plans must be updated and amended at regular Vanderlinde, R. & Van Braak, J. (2010). Implementing an ICT curriculum in intervals. a decentralised policy context: Description of ICT practices in three Flemish primary schools. British Journal of Educational Technology, 41, 139-141. Vanderlinde, R., Van Braak, J. & Dexter, S. (2012). ICT policy planning in a context of curriculum reform: Disentanglements of ICT policy domains and artifacts. Computers & Education, 58, 1139-1350. Vanderlinde, R., Dexter, S. & Van Braak, J. (2012). School-based ICT policy plans in primary education: Elements, typologies, and underlying processes. British Journal of Educational Technology, 43, 505-519. 28 29 4 Handwriting versus typing: What does neuroscience have to say? Jolien C. Francken (MSc, MA) Donders Institute for Brain, Cognition and Behavior, Center for Cognitive Neuroimaging, Radboud University, Nijmegen ‘Steve Jobs’ schools, iPad apps for babies and a school laptop for every child: computers are an indispensable part of education for the current generation of children. In the media, experts lock horns with one another in their efforts to prove or disprove that this is progress. One of the opponents of computer use by children is Manfred Spitzer, a German psychiatrist. In his book, Digital Dementia, he contends that children learn from human contact, from genuine experiences – and not from computer screens. One of Spitzer’s claims is that handwriting is es- Paradoxically enough, digital tools can actually sential to the development of children’s reading provide support for handwriting. The ‘abc Pocket skills: “Young Chinese children who learn and write Phonics’ app is only one of many computer characters on the computer do not retain them as programs designed to help children improve their well. You have to draw them, with your own hands. handwriting skills on a computer, tablet, or interac- That’s how you remember them! That’s how our tive whiteboard. brain works” (NRC Next, June 25, 2013). 30 Know What Works and Why • 4W • English Edition, October 2013 31 But what effect does typing have on reading and from one another even when they are presented writing skills? And do people who rarely write by in different sizes and typefaces, you have to pay hand lose certain motor or cognitive skills? Are specific attention to certain characteristics of the there differences in brain activity between hand- letters while ignoring others. writing and typing? Little proper scientific research Researchers believe that children learn to has been done regarding these questions, in make this distinction by handwriting letters. Their part because it is difficult to find two groups to handwriting is not particularly stable at first, and compare: very few people refrain completely the resulting variation in the letters they write is from using computers. Despite this, a number essential to that process. The very fact that they of studies are trying to answer these questions. both write and see differing versions of a letter Effect of typing on motor skills Figuur 1: The characters that adults had to learn to recognize as part of the study conducted by Longcamp, et al., 2008 teaches them its crucial, fixed characteristics. The researchers tested this hypothesis by there were differences in the development of If you write by hand infrequently, your penman- teaching letters to a group of children who had the ‘reading area’ of the brain. Handwriting and the learning of new motor programs ship skills will deteriorate and you will probably not yet learned to read, either by having them In a follow-up study, the researchers specifi- In addition to the hypothesis that writing by write slower – this will not come as a surprise to write the letters by hand or by simply showing cally examined the difference between typing hand results in more variation and thus to im- anyone. But do your fine motor skills in general them the letters. Both groups learned to recognize and writing by hand. The outcome was the proved performance in learning letters, there is also suffer if you type more than you handwrite? the letters, but only the group that learned them same: the left fusiform gyrus area was more another, complementary explanation. There is a One study compared two groups of adults: a by handwriting them had higher levels of brain active when viewing letters learned by hand- strong link between observing and acting: you ‘computer’ group (that primarily used a computer activity in the left fusiform gyrus area (an area of writing them than it was when viewing letters learn observation skills better when you perform for word processing), and a ‘handwriting’ group. the brain that is engaged when adults read letters) learned by typing them or following their shape the related action. The same is true for reading Both groups were asked to complete a number of when viewing the letters (James, 2010). with a finger. That means that it is the act of and writing. But how does that work, exactly? tests designed to test their fine motor skills. What do differences in brain activity matter if writing the letters by hand that activates this area When a person learns to write a letter by On one of the tests, in which the participants both groups of children learned to recognize the of the brain (James & Engelhardt, 2012). hand, a specific motor program is stored in their were asked to use a pen to follow a line without letters? Children are not born with specialized In other words, even in children who have not brain: a kind of description of the precise move- going off the line, the computer group completed ‘reading’ or ‘writing’ areas in their brain: these yet learned to read, handwriting activates the ments that must be performed in order to write the task much more slowly than the handwriting are areas they develop in childhood through same area of the brain that is activated in adult a certain letter. This motor program is activated group (Sulzenbruck et al., 2011). This implies that their experience with language. Child develop- readers when they see a letter. This does not when you want to write the same letter again. typing more and handwriting less affects not just ment researchers often study adults first to see happen if children learn letters by typing them. Neuroscientists believe that the same motor pro- penmanship, but other related basic motor skills how the brain functions once development is One explanation for this is that there is a wider gram is also activated when you see that letter. as well. complete. They then compare this with the brain variety produced in letters that are written by When you learn a new letter by typing it, you activity of children – in this case children who hand. If that were the only difference children do not create the unique motor program that had not yet learned to read. The brain activ- would also be able to better remember them accompanies the handwriting of that letter. This ity of the group of children who learned letters when being shown the letters in different type- is because the action of typing has no intrinsic Letter recognition is an early phase of learning by writing them by hand demonstrated more faces. This has not yet been studied, but there relationship with the shape of the letters – you to read fluently. The speed and accuracy with ‘adult’ brain activity than the group of children seems to be yet another important difference make the same movement regardless of which which kindergartners can identify letters is a good who learned letters simply by looking at them. between handwriting and typing. key you press. The link that is created by typing predictor of their future reading skills (James & In other words: both groups of children could Engelhardt, 2012). In order to distinguish letters recognize the letters after being trained, but The effect of handwriting on reading skills 32 does nothing to teach you to recognize letters. 33 Figure 2: Areas of the brain that are more active when test subjects observe letters they learned by writing rather than by typing (Longcamp, et al., 2008). MidFG IFG 4 PCL 0 IPL z = 19 z = 37 z = 61 Handwriting versus typing adults when they are reading are also activated in These studies show that writing by hand has a children who learn letters by handwriting. substantially different effect on various cognitive functions than typing on a keyboard. Researchers Although these studies point to a single conclu- believe that this difference is attributable to the sion – that handwriting is different from typing motor activity – the act of handwriting itself. First, – there is no evidence that children who do not handwriting instills better fine motor skills. Sec- have the motor skills acquired by handwriting are ond, reading (observing and recognizing letters) unable to learn to read. The studies simply show uses information from the motor programs you that a motor component in reading education use to write letters, and children do not develop makes learning to read easier. those motor skills, or develop them as well, when they learn letters by typing. Moreover, the varia- This paper originally appeared in Dutch in 4W tion in children’s letter production is essential to 2013(3) as Schrijven versus typen: wat zegt de their learning the fixed characteristics of letters, neurowetenschap? (pp. 6-13). Translation: which contributes to their ability to recognize Balance Translation, Maastricht. letters and distinguish them from one another. Finally, the areas of the brain that are active in Does that mean you will be less able to remem- performing, imagining, and observing actions ber the letter? (Longcamp et al., 2008). One study involved adults who had to learn A similar study, in which the subjects were Jolien Francken new letters, either by writing them by hand or by children who had not yet learned to read, also Author j.francken@donders.ru.nl using a keyboard. The researchers then admin- showed that the subjects recognized the letters istered a test to determine whether the subjects they had learned by writing them by hand better recognized the orientation of the new letters (as than they did the letters they had learned on the a reader does when identifying a ‘b’ versus a computer (Longcamp et al., 2005). ‘d’) while simultaneously measuring their brain Learning letters by writing them by hand activity with an fMRI scanner. results in better recognition of the new letters, Jolien Francken is a Ph.D. candidate at the The subjects recognized the letters better both by adults and by children who have not yet Donders Institute for Brain, Cognition and and for a longer period of time if they had writ- learned to read. When subjects are shown the Behavior, Center for Cognitive Neuroimaging ten them by hand. These subjects’ brain activity newly learned letters, the areas of the brain in- at Radboud University in Nijmegen, the was greater in a number of areas when a volved with motor activity are activated, but only Netherlands. She works in the research groups comparison was made between letters learned if they learned those letters by handwriting them. headed by Peter Hagoort and Floris de Lange by handwriting and those learned by typing: This shows that letter-specific motor programs and is investigating the influence of language on Broca’s area (IFG) and the left and right parietal are involved in reading as well as in writing. perception. areas (IPL). We know from earlier research that these areas of the brain are involved in 34 35 What we know about writing versus typing Want to know more? James, K.H. (2010). Sensori-motor experience leads to changes in visual processing in the developing brain. Developmental Science, 13(2), 279-288. Learning letters and writing them by hand results in four differences in compa- James, K.H., & Engelhardt, L. (2012). The effects of handwriting experience on rison to typing: functional brain development in pre-literate children. Trends in Neuroscience and Education, 1(1), 32-42. ● Handwriting creates a unique motor program for the letter in the motor areas of the brain, which contributes to letter recognition. Longcamp, M., Boucard, C., Gilhodes, J.C., Anton, J.L., Roth, M., Nazarian, B., & Velay, J.L. (2008). Learning through hand- or typewriting influences ● Handwriting produces more variation. This promotes abstraction, which is important in letter recognition. ● Children who have not yet learned to read activate the adult ‘reading’ visual recognition of new graphic shapes: behavioral and functional imaging evidence. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 20(5), 802-815. Longcamp, M., Zerbato-Poudou, M.T., & Velay, J.L. (2005). The influence area of the brain more when they see a letter they learned by hand- of writing practice on letter recognition in preschool children: a comparison writing than when they see a letter they learned by typing. between handwriting and typing. Acta Psychologica, 119(1), 67-79. ● People who frequently write by hand have better basic motor skills. Sulzenbruck, S., Hegele, M., Rinkenauer, G., & Heuer, H. (2011). The death of handwriting: secondary effects of frequent computer use on basic motor skills. Journal of Motor Behavior, 43(3), 247-251. 36 37 5 Practical examples as a resource for professional development Jo Tondeur, Natalie Pareja Roblin, Johan van Braak Ghent University Figure 1: Model for using practical examples as a resource for professional development IMPACT ON THINKING • Affirmation • Broadening • Strategic thinking CAREFUL AND COMPLETE PRESENTATION Petra Fisser Netherlands Institute for Curriculum Development (SLO) Joke Voogt INNOVATIVE CONTENT USABLE IN TEACHER’S OWN PRACTICE EXAMPLES OF EDUCATIONAL PRACTICE University of Twente Seeing how colleagues use ICT in their classrooms can be inspiring – “I’m going to do it that way, too!” – but simply copying someone else’s example is not a fundamental change in behavior. To achieve that, one’s personal views must also evolve. Examples of educational practice that SPECIFIC DIRECTIONS FITS INTO POLICY AND ICT INFRASTRUCTURE promote such evolution contribute to teachers’ professional development. We’ve all seen the short ‘educational and enter- cusses such examples of educational practice (in taining’ films shown on study days for teachers; short: practical examples) because, if they meet the ones that show practical, real-world classroom certain conditions, they can inspire teachers to examples, such as teachers demonstrating how integrate ICT into their daily classroom teaching. IMPACT ON ACTIONS • Superficial use • Adoption/Imitation • Adaptation to use a new ICT application. This article dis- 38 Know What Works and Why • 4W • English Edition, October 2013 39 How do practical examples promote professional development? cal example to fit his or her specific context, The use of practical examples to support teach- as the available ICT infrastructure or stu- ers’ professional development presumes that dents’ ICT skills. making adjustments for such circumstances people are inclined to follow a good example. Good practical examples can forge the link between doing and thinking, thereby promoting professional development That presumption is sometimes borne out. The second is the impact on how someone thinks: Kelchtermans and his colleagues (2008) write that • Affirmation of the individual’s own views. If observing practical examples does ‘something’ to a teacher can identify with the practical ICT the respondents. That ‘something’ ranges from in- example and the underlying educational vision, spiring them to think about their practice differently he feels as though his own views have been to getting them to make far-reaching changes affirmed. The same thing can happen if the in classroom and school practices. The fact that experience contrasts strikingly with his own teachers respond to practical examples in differ- approach: formulating grounds for rejecting a ent ways relates in part to the quality of the those practical example is also a type of professional examples, a topic we address again below. We development. first present the various responses that practical • Broadening of existing views. For many teach- examples may provoke. For the sake of complete- ers, observing practical examples provides ness, we note that the findings of Kelchtermans an opportunity to examine their own teaching and his colleagues refer to practical examples practices from another perspective and thus to in general, while this article focuses on practical broaden their views about using ICT. They put examples relating to ICT integration in education. their own knowledge and views about the role The first aspect is the impact on actions, of ICT in educational processes to the test, as meaning the specific changes that teachers make it were, increasing their ability to take well- to their behavior. Kelchtermans identifies three types of change: • Superficial use. The teacher follows tips or reasoned decisions. • Development of strategic thinking. The question of how a practical example can be ap- uses materials provided in the example, such plied in one’s own situation prompts teachers as educational software, without making to think about how they can persuade their any comprehensive changes. This was the colleagues/principal to work together on ICT type of change most frequently observed by integration. Kelchtermans and his colleagues. It results in very little professional development. • Adoption and/or imitation. The teacher adopts identified a third effect: the immediate rejection of the practical example in its entirety. Because the practical example. They observed this effect substantive knowledge of the example is lack- primarily when the respondents were unable to ing, this often leads to superficial ICT use. identify with anything in the example shown. • Adaptation. The teacher adapts the practi- 40 Finally, Kelchtermans and his colleagues also Although observing practical examples can result 41 in a wide variety of responses from teachers, using ICT, making it clear what the effects preparation and implementation. In short, The circumstances under which the practical they can only be viewed as having contributed will be in terms of efficiency, effectiveness, the teacher learns about the conditions and examples are presented to them also play a role. to the professional development of teachers if and motivation. equipment on which the example is based Simply having the teachers watch them is not and can use that knowledge to make a com- sufficient (Van den Berg, et al., 2008). Practical parison with his own situation. examples must always be seen in relation to the concrete actions (‘doing’) go hand in hand with a change in their personal views (‘thinking’). The link between thinking and doing is the key. If that 2) Usability: the example can be adopted and integrated A practical example inherently involves a 5) Presentation: careful and complete specific situation from which they originate and It is essential that the practical example must be interpreted (or reinterpreted) to suit the link is missing, there is a risk that the teacher will specific situation, making it a difficult source simply opt to superficially apply tips and tricks from which to draw general lessons. For should provide the observer with a careful teacher’s own teaching situation. Finally, collec- using the latest gadgets (Sang, et al., 2012). In the teacher, it is important that the practical and complete impression of the application. tive interpretation and analysis by the teacher’s short, professional development consists of two example answer the question of how he or This means that, in addition to the result, the colleagues acts as a validating filter for accepting elements: hands-on development and minds-on she can use it in his or her teaching. A good example should also show the goals and pro- the practical example as a useful tool for his own development. In this case, that means acting practical example shows why the ICT applica- cess that led to the result, including the ‘chal- teaching practice (Simons, et al., 2003). and thinking differently when it comes to ICT in tion in question would work in that situation by lenges’ involved, such as technical difficulties Teachers do not need to learn how to put exam- education. Good practical examples can forge devoting attention to the specific context. The and how the people involved dealt with them. ples into practice; instead, they must learn to in- the link between doing and thinking, thereby same is true for the degree to which the ICT If a practical example only presents success terpret inspiring examples from the vantage point promoting professional development (Van den application in the example can be integrated stories, it will quickly be dismissed as overly of their own context and to apply those examples Berg, et al., 2008). into multiple fields of learning and/or used idealistic and untrustworthy (Tondeur, et al., in their own teaching practice. That will enable with pupils in different grade levels. 2012). Multimedia presentations of practical them to develop new lesson plans that include examples (such as video case studies) offer the use of ICT (Tondeur, et al., 2013) and to test good opportunities for highlighting elements those lesson plans in an authentic setting. Based such as context, theory, and didactic infor- on evaluation and feedback, a practical example What makes a practical example a ‘good’ practical example? 3) Instructions for use: specific instructions The question, therefore, is what features a A good practical example specifically shows for didactic practice practical example must have to bring about this teachers how the ICT application can mation (see the article about TPACK in 4W may thus result in a new ICT application being dual effect (i.e., changing what the teacher does promote learning. It outlines what the ICT 2013:2). Good practical examples can thus introduced to the classroom. and how he thinks). In other words, what makes application will demand from the teachers: present ICT as both an end and a means. a practical example a “good” practical example? the roles they will be expected to play, the If we put ourselves in the teacher’s place, we activities they will be able to offer, and how realize that an example must answer all the they can determine whether the material was From observing examples to integrating ICT in the classroom questions he might pose: “What is innovative successfully learned (Van den Akker, 1988; If a practical example meets the above criteria, about the ICT application?” “How can I use it in Voogt, 2010). it will likely be a source of inspiration for profes- my teaching?” “What does this mean for me in terms of my teaching methodology?” “Do we as a school already have everything we need to 4) Organization: fits into ICT school policy and infrastructure In addition to answering substantive, practical example also addresses organi- the teachers to whom the example is provided. 1) Content: it is innovative and zational questions: what infrastructure will This is influenced by their personal background be needed, what software will be used, how (their experience and expectations) and the well does the example fit in the school’s ICT school context. new and demonstrates opportunities for 42 Translation, Maastricht. example does not depend exclusively on its fea- five different features: adds value to teaching practice fessionalisering (pp. 22-30). Translation: Balance in this respect is that the impact of a practical tures, but also on what those features mean to A good practical example offers something 2013(3) as Praktijkvoorbeelden als bron voor pro- sional development. An important side note pedagogical, and didactic questions, a good follow this example?” We distinguish between This paper originally appeared in Dutch in 4W policy, how much time will be needed for 43 Jo Tondeur Main author Johan van Braak, Natalie Pareja Roblin, Petra Fisser & Joke Voogt jo.tondeur@ugent.be Authors Jo Tondeur is post-doctoral researcher at Johan van Braak and Joke Voogt are senior Ghent University (FWO, Research Foundation - lecturers at Ghent University and the University Flanders). He researches school development, of Twente, respectively. They are both involved educational innovation, and instructional design. in studying ICT integration in education. His current line of research focuses on ICT integration in teacher training programs. Natalie Pareja Roblin is a post-doctoral researcher at Ghent University. She is studying the interaction between educational research and practice. Petra Fisser is a curriculum developer at SLO. She promotes continuing professional development in the field of ICT in education. 44 45 What we know about practical examples Want to know more? Kelchtermans, G., Ballet, K., Peeters, E., Piot, L. & Verckens, A. (2008). OBPWO 04.04. Goede praktijkvoorbeelden als hefboom voor schoolontwikkeling. Identificatie van determinanten en kritische kenmerken. kenmerken (English: ● Good practical examples of new ICT applications can bring about a change in how teachers act and think. Good practical examples as an impetus for school development. Identification of determinants and critical remarks). Koepelrapport (English: Linkage Report), 56 pp. Leuven: KU Leuven, Centre for Education Policy and Innovation. ● To achieve this change, a practical example must meet three conditions: it must present a specific, innovative ICT practice (example), Sang, G., Valcke, M., Van Braak, J., Tondeur, J., Zhu, C. & Yu, K. (2012). Challeng- demonstrate what it actually does (description), and explain why it ing science teachers’ beliefs and practices through a video-case-based interven- does what it does (explanation). tion in China’s primary schools, Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 40(4), 363-378. ● Simply having teachers watch practical examples of ICT applications is not enough. In order to put examples into practice, teachers Simons, H., Kushner, S. H., Jones, K. & James, D. (2003). From evidence-based must be able to interpret (or reinterpret) them to suit their own teach- practice to practice-based evidence: the idea of situated generalization. Research ing situation. Papers in Education, 18(4), 303-311. Tondeur, J., Hacquaert, J., Thys, J., Vandeput, L. & Hustinx, W. (2012). iTeacher Education: Wat leren we uit praktijkvoorbeelden? (English: iTeacher Education: What do we learn from practical examples?). Velon/Velov-conferentie 2012. Antwerp, Belgium. Tondeur, J., Van Braak, J., Sang, G., Voogt, J., Fisser, P. & Ottenbreit-Leftwich, A. (2012). Preparing pre-service teachers to integrate technology in education: A synthesis of qualitative evidence. Computers & Education, 59(1), 134-144. Van den Akker, J. (1988). The teacher as learner in curriculum implementation. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 20(1), 47-55. Van den Berg, E., Wallace, J. & Pedretti, E. (2008). Multimedia cases, teacher education and teacher learning. In J. Voogt & G. Knezek (Eds.), International Handbook of Information Technology in Primary and Secondary Education (pp. 475-487). New York: Springer. Voogt, J. (2010). A Blended In-service Arrangement for Supporting Science Teachers in Technology Integration. Journal of Technology in Teacher Education, 18(1), 83-109. 46 47 In this issue: 1. Using ICT to optimize the memorization of facts Know What Works and Why Know What Works and Why is a scientific publication of Kennisnet. Hedderik van Rijn & Menno Nijboer 2. Educational software for young children Adriana G. Bus ‘Know What Works and Why’ [Weten Wat Werkt en 3. What makes an ICT policy plan so effective? Waarom] publishes articles regarding the benefits and Ruben Vanderlinde & Johan van Braak effect of ICT applications in education. It covers ICT applications applied not only for didactic purposes, 4. Handwriting versus typing: What does but also in the school organization and in professional neuroscience have to say? development. The articles help education professionals Jolien Francken to assess whether a particular ICT application would be appropriate for them and likely to succeed in their context. English Edition, October 2013 5. Practical examples as a resource for professional development Jo Tondeur, Natalie Pareja Roblin, Johan van Braak, Petra Fisser & Joke Voogt

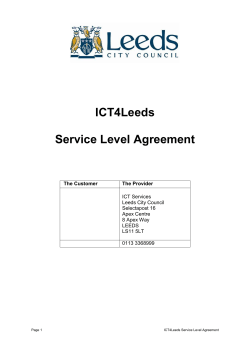

© Copyright 2025