Why Should Vancomycin-resistant Enterococci (VRE) be under Control in the

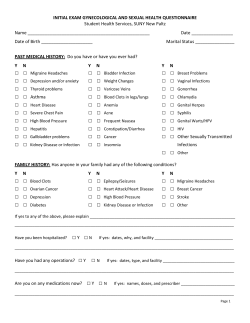

VOL.16 NO.4 APRIL 2011 Medical Bulletin Why Should Vancomycin-resistant Enterococci (VRE) be under Control in the HKSAR since the First Importation in 1997? Dr. Vincent CC CHENG MBBS, MRCP, FRCPath, FHKAM(Pathology) Clinical Microbiologist & Infection Control Officer, Queen Mary Hospital Dr. Vincent CC CHENG Introduction screened was found to harbour VRE in the stool 12. Enterococcus is a facultative anaerobic gram positive coccus which normally colonises our gastrointestinal tract. Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis may cause serious infections, including endocarditis, urinary tract infections, intra-abdominal and pelvic infections, especially in patients with indwelling devices and immunocompromised states. Vancomycin-resistant E. faecium and E. faecalis (VRE) were first reported in France and the United Kingdom in 1986 1,2. Since then, VRE have spread throughout the world and have become an important agent causing nosocomial infections. During the 1990s, a significant increase of VRE was observed in the United States from 0.3% of all isolates in 1989 to over 28% in 20043,4. Reported risk factors for gastrointestinal colonisation of VRE include hospitalisation, residence in long-term care facilities, use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, renal replacement therapy, and admission to high risk clinical areas5-7. The outbreak of VRE in Europe was mainly related to the widespread use of avoparcin, a vancomycin analogue, in the farm animal industry, while the outbreak in the United States was mostly attributed to the consumption of vancomycin in the healthcare setting8. Avoparcin was banned in livestock industry by European Union in 1997, the prevalence of VRE in healthy persons decreased in several European countries 9 . Inappropriate use of vancomycin not only poses a threat to the emergence of VRE, but also vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (VRSA), involving the in-vivo transfer of vanA genes from VRE to S. aureus isolates as has been reported previously10. As methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) has been endemic in our locality in the past two decades and control of its nosocomial transmission has been difficult, infection control professionals have learnt the importance to combat against the potential outbreaks of VRE and VRSA during the non-endemic phase in Hong Kong. Since VRE have not yet disseminated in the community and hospitals in Hong Kong, we are able to focus our resources on the promotion of strategic infection control measures to prevent the nosocomial transmission and outbreak of VRE (Table 1). As enterococci constitute part of the normal gut flora, eradication after their colonisation in the gastrointestinal tract is very difficult and the shedding of VRE can be up to 2 years 13 . Therefore, when there is a sporadic case of VRE being identified in a hospitalised patient, the infection control team will immediately isolate the index case in a single room with strict contact precautions, conduct extensive investigations to find out the source, perform contact tracing of the potential secondary cases, and carry out environmental surveillance and disinfection to control the spread of VRE in our hospitals14. Epidemiology and Control of VRE in Hong Kong VRE are uncommon in Hong Kong. Since the importation of VRE in 1997, there have been sporadic cases of VRE colonisation or infections and outbreaks of a limited scale in renal, medicine, and orthopaedic units. In a prospective screening programme of all patients admitted to ten intensive care units between August and November 1999, 2 (0.12%) out of 1697 strains of enterococci were found to be VRE 11. In an active surveillance study in a regional hospital between 2001 and 2002, only 1 out of almost 1800 patients being Table 1. Infection control measures in prevention of nosocomial transmission of vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) at Queen Mary Hospital General measures 1) Education of infection control practice to healthcare workers (i) Mandatory infection control training course for all healthcare workers (ii) Collaboration with infection control linked nurses 2) Enhanced infection control practice (i) Enforcement of standard and transmission based precaution in clinical area and provision of alcohol based hand rub in every bed, all ward entrances and corridors (ii) Regular environmental cleaning per protocol 3) Audit of infection control compliance and antibiotic consumption (i) Unobtrusive hand hygiene observation and monitoring the consumption of alcohol based hand rub in the hospital (ii) Antibiotic stewardship programme to reduce the inappropriate use of vancomycin Specific measures 1) Active surveillance culture for high risk patients (i) Patients who had history of hospitalisation or received operation outside Hong Kong in the past 12 months (ii) Implementation of rapid diagnostic test to shorten the turn around time and immediately inform Infection Control Team for positive result 2) Intervention for sporadic case of VRE (i) Single room isolation with contact precautions (ii) Extensive environmental cleaning sodium hypochlorite 1000 ppm, especially in the toilet (iii)“Just-in-time” education session for ward staff (iv)Contact tracing for secondary case by VRE screening to all exposed persons in the same ward within a defined period (v) Labelling of VRE status at hospital computer system (CMS) and alert Infection Control Team upon patient’s readmission Illustrated Example of an Outbreak Investigation and Control of VRE On 28 March 2009, VRE was isolated from the catheterised urine in a 77-year-old man (patient 1) hospitalised in the neurosurgical unit of hospital A. The patient was immediately transferred into an isolation room with contact precautions and screening of 28 other patients in the same unit was performed. The VRE 26 VOL.16 NO.4 APRIL 2011 Medical Bulletin were detected in the stool samples of two other patients including a 62-year-old lady (patient 2) and a 75-year-old man (patient 3). The starting date of the outbreak period was thus defined as 3 March 2009, on which day patient 3 was admitted. Further contact tracing was performed which included 58 patients who had been transferred to the 4 convalescent hospitals since 3 March 2009 and remained hospitalised at the time of investigation. VRE were isolated from the stool of another 89-year-old man (patient 4) who was transferred to hospital B on 16 March 2009. Seventy-one out of 89 patients discharged from hospital A and another 35 patients staying with patient 4 in hospital B were traced and screened for VRE. A total of 192 patients were screened with 3 (1.6%) of them being colonised with VRE. All patients confirmed to be VRE positive were cared for in isolation rooms with contact precautions, and hand hygiene was enforced with an emphasis on directly observed hand hygiene practice. Seven specimens of 7 household members (one specimen each) from patients 1, 2 and 3 were negative for VRE by voluntary screening. A total of 440 and 66 environmental samples were collected in hospital A and hospital B respectively, and two of them taken in hospital B (bedside table and milk container) were positive for VRE. Our epidemiological investigation showed that patient 4 could be the possible index case of this outbreak. He was directly transferred from a hospital in China and admitted to the neurosurgical intensive care unit for management of chronic subdural haematoma on 3 March 2009, and treated with broad spectrum antibiotics for nosocomial pneumonia. The use of antibiotics may increase the microbial load of VRE and facilitates the nosocomial transmission of VRE to patient 1, 2, and 3. Our case-control study has identified advanced age, presence of indwelling nasogastric tube and endotracheal tube, and the use of beta-lactams antibiotics and vancomycin as the significant risk factors for nosocomial acquisition of VRE. All index and secondary cases were labelled as “VRE carrier” in the hospital information system in order for the infection control team to implement appropriate measures when these patients are re-admitted to the hospital. Active Surveillance Culture – a Model of “Whom TO Screen” VRE have recently emerged in Asian countries such as Singapore, Japan, Korea and China15-18, it has become more difficult to maintain Hong Kong free of VRE. In addition to the ongoing antibiotic stewardship programme to minimise the antibiotic selection pressure19, we are the first hospital cluster to introduce the active surveillance culture programme to detect the presence of multiple drug resistant organisms among the high risk patients upon admission since December 2009. Basically, it is a model of “whom TO screen”. T means “travel” as in medical tourists and O stands for “operation outside Hong Kong”. Triage personnel in the emergency room or admission ward will enquire on whether the patient had a history of medical tourism or operation outside Hong Kong in the past 12 months (Figure 1). For patients fulfilling the criteria of TO, the infection control team will follow them up by collecting relevant clinical specimens and coordinate with the laboratory for rapid identification of a panel of resistant 27 pathogens including MRSA, community-acquiredMRSA, VRE, and the recently identified carbapenemresistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) carrying NDM-120. Once the colonisation or infection status of multiple drug resistant organisms is confirmed, appropriate infection control practices will be implemented. Figure 1. Active surveillance culture for early detection of multiple drug resistant organisms at Queen Mary Hospital Acknowledgment We thank our frontline healthcare workers for their active participation in the infection control measures to prevent the nosocomial transmission of multiple drug resistant organisms. The description of the VRE outbreak has been published and permission to reproduce the portion of published material has been obtained from the editorial office of Emerging Health Threats Journal. References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. Leclercq R, Derlot E, Duval J, Courvalin P. Plasmid-mediated resistance to vancomycin and teicoplanin in Enterococcus faecium. N Engl J Med 1988;319:157-61. Uttley AH, Collins CH, Naidoo J, George RC. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Lancet 1988;1:57-8. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) system report, data summary from January 1992-April 2000, issued June 2000. Am J Infect Control 2000;28:429-48. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) System Report, data summary from January 1992 through June 2004, issued October 2004. Am J Infect Control 2004;32:470-85. Rao GG, Ojo F, Kolokithas D. Vancomycin-resistant gram-positive cocci: risk factors for faecal carriage. J Hosp Infect 1997;35:63-9. Dever LL, China C, Eng RH, O'Donovan C, Johanson WG Jr. Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium in a Veterans Affairs Medical Center: association with antibiotic usage. Am J Infect Control 1998;26:40-6. Brown AR, Amyes SG, Paton R, Plant WD, Stevenson GM, Winney RJ, Miles RS. Epidemiology and control of vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) in a renal unit. J Hosp Infect 1998;40:115-24. Tacconelli E, Cataldo MA. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE): transmission and control. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008 Feb;31(2):99-106. van den Bogaard AE, Bruinsma N, Stobberingh EE. The effect of banning avoparcin on VRE carriage in The Netherlands. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000 Jul;46(1):146-8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vancomycinresistant Staphylococcus aureus--Pennsylvania, 2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51:902. Ho PL; Hong Kong intensive care unit antimicrobial resistance study (HK-ICARE) Group. Carriage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, ceftazidime-resistant Gram-negative bacilli, and vancomycin-resistant enterococci before and after intensive care unit admission. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1175-82. VOL.16 NO.4 APRIL 2011 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. Chuang VW, Tsang DN, Lam JK, Lam RK, Ng WH. An active surveillance study of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus in Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 2005;11:463-71. Mascini EM, Jalink KP, Kamp-Hopmans TE, Blok HE, Verhoef J, Bonten MJ, Troelstra A. Acquisition and duration of vancomycinresistant enterococcal carriage in relation to strain type. J Clin Microbiol 2003;41:5377-83. Cheng VC, Chan JF, Tai JW, Ho YY, IWS Li, To KK, Ho PL, Yuen KY. Successful control of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium outbreak in a neurosurgical unit at non-endemic region. Emerging Health Threats Journal 2010, 2: e9. Yang KS, Fong YT, Lee HY, Kurup A, Koh TH, Koh D, Lim MK. Predictors of vancomycin-resistant enterococcus (VRE) carriage in the first major VRE outbreak in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2007;36:379-83. Hosh u ya m a T, M o r i g u c h i H , M u r a t a n i T, M a t s u m o t o T. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) outbreak at a university hospital in Kitakyushu, Japan: case-control studies. J Infect Chemother 2008;14:354-60. Oh HS, Kim EC, Oh MD, Choe KW. Outbreak of vancomycin resistant enterococcus in a hematology/oncology unit in a Korean University Hospital, and risk factors related to patients, staff, hospital care and facilities. Scand J Infect Dis 2004;36:790-4. Zheng B, Tomita H, Xiao YH, Wang S, Li Y, Ike Y. Molecular characterization of vancomycin-resistant enterococcus faecium isolates from mainland China. J Clin Microbiol 2007;45:2813-8. Medical Bulletin 19. 20. Cheng VC, To KK, Li IW, Tang BS, Chan JF, Kwan S, Mak R, Tai J, Ching P, Ho PL, Seto WH. Antimicrobial stewardship program directed at broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics prescription in a tertiary hospital. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;28:1447-56. Kumarasamy KK, Toleman MA, Walsh TR, Bagaria J, Butt F, Balakrishnan R, Chaudhary U, Doumith M, Giske CG, Irfan S, Krishnan P, Kumar AV, Maharjan S, Mushtaq S, Noorie T, Paterson DL, Pearson A, Perry C, Pike R, Rao B, Ray U, Sarma JB, Sharma M, Sheridan E, Thirunarayan MA, Turton J, Upadhyay S, Warner M, Welfare W, Livermore DM, Woodford N. Emergence of a new antibiotic resistance mechanism in India, Pakistan, and the UK: a molecular, biological, and epidemiological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:597-602. 28

© Copyright 2025