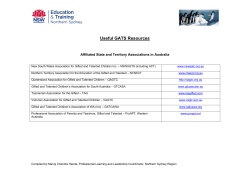

Document 245640