Why Thai SMEs do not register for IPRs?: Piriya Pholphirul

Why Thai SMEs do not register for IPRs?: A Cost-Benefit Comparison and Public Policies Piriya Pholphirul* and Veera Bhatiasevi** Abstract Intellectual property (IP) refers to an intellectual creation of human beings which are manifested in any form or manner. Intellectual property right is the rights to reap economic benefits from inventions, technologies, products and services constructed based on a producer’s intellect and ability. Nevertheless, the Thai business sector, especially small and medium enterprises (SMEs) usually lack the understanding of how intellectual property constitutes competitive advantage. It has been found that SMEs are threatened to lose their stand in the international trade platform. As witnessed, a large number of Thai SMEs do not apply for intellectual property protection. In order to clarify why the Thai SME do not register intellectual property, our analysis is categorized by cost and benefit. Based on the findings, policy recommendation proposed here will touch upon strategic management of intellectual property, how to drive performance at a policy level, and the role of other agencies relevant to SME intellectual property Keywords: Intellectual Property Rights, Small and Medium Enterprises, Thailand * School of Development Economics, National Institute of Development Administration (NIDA). Corresponding Address: Serithai Road, Klong-Chan, Bangkapi, Bangkok 10240, Thailand. Email: piriya.p@nida.ac.th ** Business Administration Division, Mahidol University International College (MUIC). Corresponding Address: Buddhamonthon, Salaya, Nakhon Pathom, 73170, Thailand. Email: icveera@mahidol.ac.th This research paper was funded by the Mahidol University International College (MUIC) SEED Grant program. All mistakes appearing in this paper are the authors’ responsibility. I. Introduction Intellectual property (IP) refers to an intellectual creation of human beings which are manifested in any form or manner. Such creation may be abstract work including skills, theories and methods of production or can be materialized into concrete products including inventions and handicrafts. Both forms previously mentioned incorporate the value of knowledge, discovery and creative thinking that are infused into particular products. In law, intellectual property denotes legal entitlement that is prescribed in relation to intellectual production. A composer, for instance, possesses the rights to prohibit a further non-permitted reproduction of his/her work. Endowed with similar legal rights, a recording company can also prevent the sale of pirated records and copyright infringement. Intellectual property right, therefore, is the rights to reap economic benefits from inventions, technologies, products and services constructed based on a producer’s intellect and ability. Such benefits comprise 1) monetary benefits that might occur in forms of profit accompanying with the sale of products 2) benefits that arise in transferring and allowing others to practice the rights. With a license, the transferees are able to produce, reproduce, adapt, copy and exhibit particular work or products to the public. In general, the rights conferred are regarded as exclusive to the proprietors. The right holders are protected by public and private legal rules with the rights to claim compensation, put an end to the proprietors’ actions e.g. the sale of IP infringed products, or pursue public legal procedures. Intellectual property offences are punishable with fine and imprisonment. Intellectual property protection also plays an essential role in preventing others except the inventors from practicing or making use of the inventions. The protection is classified into several categories based on legal procedures, as well as administrative measures in preventing intellectual property infringement. Previous studies on intellectual property generally focus on IP rules and regulation highlighting IP laws as a subject of analysis. This research, however, places an emphasis on cost-benefit analysis under an economic point of view with a purpose to broaden the understanding on intellectual property. The discrepancy between the legal and economic perspectives on intellectual property lies on the notion that the latter pays attention to the private benefit that the producers will gain and the public benefit that may go further to what the country may obtain in terms of consequences and national development. Cost-benefit analysis on intellectual property would contribute to an appropriate level of protection with a due consideration to market competitive structure and other relevant aspects Nevertheless, the Thai business sector, especially small and medium enterprises (SMEs) usually lack the understanding of how intellectual property constitutes competitive advantage. It has been found that SMEs are threatened to lose their stand in the international trade platform. As witnessed, a large number of Thai SMEs do not apply for intellectual property protection. One potential factor is perhaps an unawareness of intellectual value of their ideas or products. Another case is that SMEs, by carelessness and negligence, fall as defendants for putting on sale products with copied trademarks (yet, certain SMEs may have an intention to do so). However, in consideration of their significance, SMEs are regarded as a mechanism that has driven the Thai economy. This is due to the very fact that SMEs’ performance accounts for 42 percent of Thailand’s Gross Domestic Products (GDP); their number is equivalent to 99 percent of domestic registered companies. Thus, to achieve economic development and increase public welfare, SMEs must be encouraged to learn and be aware of intellectual property with an enforcement of appropriate protection and support for research and development (R&D) within 2 SMEs. This would strengthen the potential of Thai businesses and SMEs’ capacity to compete domestically and internationally. The objective and contribution of this paper is in understanding why Thai SMEs do not register for intellectual property rights and how Thai’s policymakers should implement such appropriate IPR policies. In the next section, we will explain the importance of SMEs to the Thai economy and how the IPRs are very important for determining the competitiveness of the Thai SMEs. Section III explains how the Thai SMEs manage their IPRs. Section IV will analyze the methodology from in-dept interviews and find why Thai SMEs do not want to register for IPR by using a cost-benefit comparison from their registration of the IPRs. Finally, Section V explains policy recommendations and concludes. II. Importance of SMEs to the Thai Economy SMEs are a major group of enterprises that take a crucial part in economic and social development, especially in developing countries like Thailand. SMEs have maintained a steady growth and performed an essential role in stimulating domestic investment as the business is initially operated by new entrepreneurs and potentially developed into a large-sized enterprise. In addition, SMEs account for a significant rate of employment in both formal and informal sector at a national level, as well as vocational training. SMEs heighten value-added production, establish a competitive atmosphere that helps reduce the monopolistic power of large-size enterprises and pave way towards a more effective allocation of resources. A classification of SMEs is determined by the criteria that vary across countries. Some adopt registered capital, capital expenditures or turnover as a standard, while Thailand’s definition of SMEs is based on the number of employees, fixed asset or paid up capital labeled in ministerial regulations. According to the 2002 Business Trade and Service census conducted by the National Statistical Office on every enterprise except hawkers and vender stalls, Thailand had in total 1,641,250 large, medium and small-sized enterprises in 2001 with 99 percent or 1,624,840 being medium and small enterprises.1 Under a classification of the enterprises based on whether they were located in municipal or Tumbol Administration Organization areas, 828,305 SMEs were found within Tumbol Administration Organization areas.2 A closer look into the 1999 employment statistics reveals that SMEs shed some light on the growth dynamics of overall employment in Thailand with approximately 6.6 million persons engaged in comparison to the number of 5.2 million in 1994. The employment rate of SMEs maintains a 4 percent annual growth on the average. In terms of employment figures, there were 0.88 million people (10.6 percent of gross national employment) and 5.7 million (68.6 percent of gross national employment) engaged in medium and small-sized enterprises respectively. The 1 The figure can be divided into 358,925 in manufacturing sector (22 percent), 783,001 in commercial sector (48 percent), and 499,324 in service sector (30 percent). Within the service sector, the enterprises fall into the domain of hotels and restaurants (11 percent), recreation (8 percent) and transportation (5 percent) respectively. The percentages are calculated based on the number of enterprises in the sector. 2 There are still other small-sized and community enterprises that are not listed in the census. Their number can be estimated based upon the Household Industry Survey conducted by the National Statistical Office. Data are collected from the establishments that are engaged in production intended for sale and confined to the precincts of the house with less than 10 workers participating. In 2001, household industry is conducted in 1.174 million households with 482,180 in the North-East (41 percent), 325,604 in the South (27.7 percent) and the rest scattering all over the country. 3 remaining 1.7 million people or 20.7 percent remains with large-sized enterprises. The SME employment figure can be broken down into 1.9 million persons in manufacturing sector, 2.5 million in business and trade sector, and 2.2 million in service sector. SMEs contribution to the country’s GDP is equal to 2.1 million baht or 42 percent out of 4.9 million baht GDP3. Nevertheless, the present world economic and political environment and their future trends are crucial factors that form an inextricably linkage with the operation of SMEs, especially in the age of Information and Communication Technology (ICT). With a widespread of computers, information system advances positive effects on every enterprise and organization in facilitating creation, production and administrative efficiency. For instance, electronic commerce helps distribute goods and commodity in a more effective manner resulting in a shorter product life cycle. In this scenario, an entrepreneur is required to launch new products into the market. The consequences can be both opportunity and threat. Without an ability to adapt itself in a timely manner, an organization may encounter strategic challenge and crisis. Therefore, SMEs are needed to enhance their competitiveness and competitive advantage in such aspects as entrepreneurship, technological development, production, marketing and financial management. One of the major approaches leading to higher competitiveness is to encourage innovation and intellectual capital within the organizations. SMEs must develop an understanding on knowledge management (KM). KM encompasses the notions of information management, knowledge and skill development and data collection. The concept also touches upon intellectual properties invented or designed by SMEs, and innovation that enables higher-quality products and unique methods of production. Without efficiency of production, SMEs under a presence of other limitations are rendered the inability to compete with large-sized enterprise4. Moreover, in light of the present situation where organizations must adapt to structural change of the domestic industry and government policies on trade, service and investment liberalization, SMEs are likely to face an even more condensed competitive rivalry. Thus, SME supporting strategic plans are demanded to place an emphasis on how the organizations could achieve competitiveness through the exploitation of intellectual property. Policymakers must provide support in raising the understanding of intellectual property and its correspondence to organizational value to which SMEs could contribute as inventors or legal licensees in certain cases where intellectual property belongs to large-sized enterprises. This would maximize the competitiveness of Thai entrepreneurs and establish a road to national development5. III. The Intellectual Property Management of the Thai SMEs 3 However, it is not speculated whether the employment is subsumed under the formal sector or has included the informal sector into it. If the latter assumption holds true, the employment in small and medium-sized enterprises must be exceedingly higher. 4 The production efficiency might mean the ability of production or service with lower average cost. Generally, the large enterprise will have more advantage than the small and medium enterprises on the economies of scale. 5 Under the Small and Medium Enterprises Act B.E. 2543 (2000), Section 43, it established “the small and medium enterprises support fund” monitored and controlled by Office of Small and medium Enterprises Promotion (OSMEP) in order to financially support the loan of small and medium enterprises for launching, establishing, improving, and developing efficiently the business of small and medium enterprises. 4 Regarding a study by Schumpeter (1912), large business units have the ability to create more innovation than the small business units because the large business units always gain utility from the intellectual property in the amount of profit they make. These units will also gain profit from the research and development investments6. Besides, innovation is also developed for the overall benefit of the society as a whole. Many studies that followed and supported Schumpeter are concepts that intellectual property development will be successful because of the investment potential of the large companies. Large companies can access more finance and human resources. Large companies can also control the production costs and lines in order to learn newer and more effective innovations. However, there are the some studies that rejected Schumpeter’s hypothesis. They explained that the small business units might be able to create innovation far more than the large business units. Although the large business units gain more benefit from production than the small companies, there is no evidence to directly support the relationship between the amount of production and the efficiency of innovation creation (Symeondis, 1996). In the meantime, the capability of innovation creation might be prescribed not only by the size of the business unit or its financial capability but also on other significant factors7. Although their factors support the view that small business units might be efficient enough in creating new innovations to the market, the main problem is that the small business unit might not be able to gain the benefits completely because they are not able to utilize the intellectual property commercially8. Because there are not as many small companies when compared to larger companies, they cannot distribute the product to the market and make as much from the intellectual property. Therefore, the problem of small companies, with regard to intellectual property is not the capability of innovation creation; however, it is the problem of intellectual property. The formulation of proper competition policy by the government is essential for utilizing intellectual property to the benefit of the society as a whole. Although Schumpeter’s hypothesis states that large enterprises have a higher chance in creating innovation than the smaller enterprises, this hypothesis however excludes intellectual property, which emphasizes on creative products more than high technology or investments. The computational intelligence may not require the high cost of R&D when it is compared with the technological-based production such as drugs or computers. Therefore, SMEs can produce creative products of their own for capacity building and for elevating the competitiveness of the organization. Moreover inventions that are concerned with creation depend on the number of entrepreneurs within the SMEs. If there are many entrepreneurs, creation increases because each small business produces different products and services using computational intelligence. As a result of the studies, we will attempt to explain the intellectual property management of Thai SMEs. They are categorized into the following topics: 3.1. The Capability in Using Technology 6 The concept has been called “the hypothesis of Schumpeter” or the “Schumpeterian Hypotheses” (Symeonidis, 1996). That hypothesis has 2 arguments. 1) The large business organizations have created more innovation and intellectual property than the small business. 2) The organizations that create the innovation always gain the advantage from the innovation. Moreover, it initiates the monopoly power of their business. 7 Schumpeter (1942) explains the concept of “Creative Destruction” as follows, that “although the new innovation has created utility for the society, that innovation might destroy other innovations. Therefore, the concept of “Creative Destruction” suggests that there are gainers and losers for the new innovations. 8 As shown by the examples from the studies of Scherer (1992), Geroski (1994), Gambardella (1995), Cohen (1995), Gruber (1992, 1995), and Sutton (1998). 5 Intellectual property can be provided in the form of new technology or innovation for the creation and effectiveness of production. The problem mostly is that SMEs have not realized the significance of new innovation for product creation; also, they have not perceived lack of the relevance of innovation and the IP system. The capability in using technology by Thai SMEs is limited to the use of Computer Aided Design (CAD), Computer Aided Manufacturing (CAM) and Computer Aided Engineering (CAE). That is why the SMEs are not efficient enough in creating new products for the market9. Thai SMEs usually perceive technology as the information of the arrival of new machinery and production technology within their industry. That information comes from customers, magazines, equipment sales representatives, material manufacturers, and exhibitions. In this regard, the capability of information perception of SMEs is significant for the development of innovation of the organization. Being technology driven is essential to SMEs (service business) because it provides the opportunity for sustainable competition. The service business always emphasizes on value creation rather than the function of products; thus, SMEs recognize the significance of electronic commerce for launching a business. However a survey done by the Office of Small and Enterprises Promotion, found that computers are not used for electronic commerce purposes as much as they should. Generally, Thai SMEs tend to only use computer software in relation to accounting and financial aspects. Besides that they also use (slightly) other programs for production and product selling such as Electronic Data Interchange (EDI), which is a program that is used in increasing the effectiveness of production. 3.2. The Capability of Innovative Creation From the Schumpeter’s point of view, SMEs cannot create innovation because they lack investments, especially innovations that require high technology. Besides, some kinds of innovation are complex; therefore, SME personnel’s have to spend a lot of time and effort in learning the new innovation which leads to high cost and complexity. Many Thai SMEs have the ability in applying the product to the market demand or in slightly adjusting the marketing process to be effective. Some SMEs also have the ability to improve the production process to be more efficient. SMEs usually produce parts based on the design of the customers including the sketch and design followed by the characteristics that customers require. However, not many enterprises are able to design high level products such as prototype parts. Moreover, it was found that most SMEs do not have an R&D department of their own. That is why they lack the ability to develop research for supporting and standardizing product developments. A survey conducted by the National Science and Development Agency (NSTDA), found that Thai SMEs hardly create innovation. It was found that only 7.3 percent of Thai SMEs created innovation while, only 14.4 percent of large enterprises in Thailand created innovation. In comparison the proportion is less than the innovation creation of the Korean entrepreneurs which stands at 41 percent for SMEs and 78 percent for large enterprises. Table 1: Percentage of Innovative Organization in Thailand Enterprise Small and Medium Enterprise Thailand (%) 7.3 South Korea (%) 41.0 9 As the survey of Office of Small and Enterprises Promotion, it found that the electricity and electronic industry imports the most CAE. However, the proportion is only 19percent when comparing with the whole in that industry. 6 Large Enterprise 14.4 78.0 Source: Thailand’s National Science and Development Agency. 3.3 The Potential/Capability of Laborers and Lack of Human Resource The potential/capability of laborers and human resource for Thai SMEs is still limited. The effectiveness of personnel development, unmotivated wages, salary and welfare including the profession or specialist shortage are critical for the intellectual property development such as product design and product research. Moreover, not many SMEs realize the significance of intellectual property utilization in terms of commerce. The lack of potential technicians is a major problem for the human resource sector of Thai SMEs. The average Thai laborer is poorly educated and lacks the necessary development and training that is required in creating new products. Also, the technicians do not have a vision in designing and developing products for the future market. This has been a problem for entrepreneurs who seek continuous development. Currently there is also the opportunity of further education for students such as the technicians. Once they graduate in vocational education, they will choose to study at a university to further their education because they can earn higher salaries with a university degree. Generally speaking, the labor productivity in SMEs is lower than that of the large enterprise. It should be noted that, the efficiency of labor in the larger enterprises has itself decreased after the economic crisis of 199610. 3.4 . The Benefits and Costs of the Intellectual Property Patent SMEs mostly have not patented their own intellectual property because they do not realize the value of intellectual property; many do not know how or by which method they should estimate the value11. Generally, entrepreneurs can estimate the value of intellectual property as the reflection of profit from the high investment of intellectual property. Especially, when SMEs are the holder of all rights reserved. The profit stream increases substantially when it is compared with the organization without the previously mentioned criteria. SMEs also benefit from intellectual property rights when transferring the license to others who also receive the benefit of intellectual property at the price. The income of license transferring shows the willingness to pay of the purchaser, and is the market value of the intellectual property12. It is also to the mutual benefit of both organizations. 10 A study by Pholphirul (2005), found that the economic crisis in 1996 impacted labor productivity, decreasing it from 75,000 Baht per person in 1996 to 65,000 Baht per person in 1998, a drop of 13 percent in 2 years. 11 From Poltorak and Lerner (2002), Economists have come up with guidelines of intellectual property value estimation, which can be categorized as follows: • The Cost Approach: The R&D cost of intellectual property is the key to indicate its value. Thus, the value will be high if the owners have spent a lot on R&D. • The Productivity Approach: evaluates the future return of intellectual property: If the intellectual property can generate income in the future for a long period, the intellectual property will have a high value. • The Market Value Approach: the value of intellectual property will be based on the market price. 12 The intellectual property value estimation is the measurement as indicated by customer. It is different from other properties that focus on the costs of production. Some products take a long time to produce, and have high costs; however, they cannot be sold at high prices. Construction materials are an example of this. Compare this to intellectual property on music cassette tapes, which have low costs but can be sold at higher prices. There is also a high demand from the consumer. As such, the latter’s intellectual value is much higher than other properties. 7 One indirect benefit of intellectual property can be the positive image of the brand or trademark, which ensures the customer, the joint venture, and the stakeholder’s loyalty. The utilization of trademark and product design is an important key to the market success of SMEs, and it builds up their own capability to compete in the market. Although the entrepreneurs will gain the benefit from the patent, it will come at a cost for the entrepreneurs. That cost can be categorized into: 1. Monetary Cost: the entrepreneurs have to pay all the expenditure for patenting and other costs such as the lawyer’s expenses. 2. Non-Monetary Cost: this cost would include the time that the entrepreneurs need to spend on learning the law etc. and launching the patent. The Thailand’s Department of Intellectual Property lay out the costs that the entrepreneurs have to pay, namely a fixed cost for requesting the license and other steps of permission (as shown in the Table 1). The fee depends on the number of requests they make. For the patent, the entrepreneurs have to pay the expenditure annually for extending the time of the intellectual property. The extension fee will be higher year by year, especially the license fee of an invention where its cost is higher than that of other licenses. Table 2 Intellectual Property Patent Fee Fee Convention Patent Product Design Patent Convention Petty Patent Amendment Patent Announcement Petty Patent and Advertisement Convention Audit (in case of invention) Patent and Patent Legislation Objection Appeal Right Conversion Baht 500 250 250 50 250 500 250 500 250 500 100 Source: Thailand’s Department of Intellectual Property, Ministry of Commerce For the fees of the other kinds of intellectual property patents, the expenditure will be fixed. The trademark patent request will be separated into two parts. First is the requesting fee of 500 Baht per each request. After receiving approval, the requester will pay the fee and the registration of the product and service, amounting to a 300 Baht per request. At the same time, the fee of the geographical location is 500 Baht per request. The time frame of protection is limited. Therefore, entrepreneurs have to compare the costs and benefits of intellectual property patents. Some will choose a more informal method instead, such as keeping the secret of their own intellectual property or improving the production quality13. 13 Moore (1996) explains that the small and medium enterprise entrepreneurs may choose the way to get into the market before others to try to get the benefits from the intellectual property before it is copied. Ultimately, other entrepreneurs come into the market and split the market by fostering the relations with the customers and focusing on high-trust relationships (Dickson, 1996). 8 3.5. The level of Intellectual Property Protection Thailand is a member of the Order of International Agreements under conventions concerning intellectual property law. Intellectual property infringement often happens as copyright14, trademark15, and patent infringements16. Nonetheless, the level of intellectual property protection development in Thailand is not that high comparing to international standards. Thai SMEs cannot benefit or gain advantage from their own intellectual property as is the case in more developed countries. Entrepreneurs do not fully provide patent information on compulsory license, or support the data for the patent. Patent information here, means the knowledge of techniques, law and the value of the intellectual property to the organization and the stakeholders (in easy to understand language). Patent information should cover all mass media such as books and the Internet. Numbers of studies have found that the intellectual property law is complex and difficult to understand for most people. Thai entrepreneurs undeniably have infringed intellectual property by downloading images or cartoons from the Internet for their products. This often happens with SME entrepreneurs, who do not see the need for sufficient patent information, or try to economize on the cost of creating a patent. Hence there is a perceived gap for infringing patents17. In the case of a law suit, the cost of court fees, lawyers and investigation expenses are higher18. The fundamental element of almost all intellectual property lies in research and development, including invention for the purpose of creation. In the past, investment in R&D, especially science technology, was for the most part the responsibility of the government19. However, increased competition in business has seen an increase in the role played by the private sector in R&D. An overall analysis reveals a great disparity in levels of R&D, not just between developed and developing countries, but also among developing nations as well. In the case of Thailand, investment in research and development is minimal, no matter what other developing 14 Copyright infringement can be separated into 2 steps. 1) Primary copyright infringement under Section 27 of the law. It prescribes that the copyright infringement is copying, adjusting or extending the copyright product to the public. 2) Secondary copyright infringement is the act after the primary copyright infringement; it is the supporting and illegal copying and, importing and distributing to the public in such a way that might cause damage to the copyright owner (Section 31). 15 Trademark infringement happens when a person uses the trademark registered in Thailand, with an unregistered product without getting permission. It leads to the presumption that the trademark owner is the source of product. This is an infringement. 16 The Patent Act does not prescribe the infringement clearly. However, it explains that a person who acts under the exclusive right of the rights holder without any consent from the rights holder shall be subject to criminal penalty. the Patent Act B.E. 2542 Section 86). 17 Vandewage (2003) explains that the complexity of intellectual property leads to loopholes. Intellectual property law cannot be fully applied, and protect from infringements effectively. Inapplicable law becomes unenforceable law. 18 The study of Valimaki (2002), found that the value of intellectual property is higher than the value in the knowledge based industry such as the software and science equipment industry, etc. 19 An example of a state agency with the greatest role in R&D in Thailand is the National Science and Technology Development Agency (NSTDA), which has four affiliated institutes: (1) National Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (BIOTEC); (2) National Metal and Materials Technology Center (MTEC); (3) National Electronics and Computer Technology Center (NECTEC); (4) National Nanotechnology Center (NANOTEC). In addition to this, there are also other research institutes attached to various ministries and universities. 9 country is used for comparison. In 2002, Thailand invested approximately US$328 million or the equivalent of US$5.20 per person per year in research and development, amounting to only about 0.26 percent of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The majority of developed nations invest a far greater amount. For example, in 2002, the US invested a total of US$270 billion in R&D and was the world’s largest investor, followed by Japan, Germany and France. When we compare the level of investment in R&D between developed and developing countries, it is apparent that developed nations, together with newly industrialized countries (e.g. Taiwan, Korea, and Singapore) on average invest more than 2-3 percent of their GDP, while developing countries (such as Thailand) invest less than 1% of GDP in R&D. If we compare Thailand with other ASEAN nations, we discover that Singapore has the highest regional level of expenditure for R&D, equal to 2.2 percent of the country’s GDP, followed by Malaysia (0.71 percent) and Thailand (0.26 percent) respectively. In addition, in terms of R&D personnel, most developed countries have a large number of people employed or involved in the field. In Japan, for instance, there are approximately 892,000 people or 7 in every 1000 involved in R&D, followed by Germany, where the ratio is 5.8 in every 1000 people. Newly industrialized nations, such as Singapore, Taiwan or South Korea, also have a somewhat high number of people involved in R&D, equivalent to 4-5 in every 1000 people. In the case of Thailand, there are only 32,000 people or 0.51 in every 1000 people involved, comprising of 17,710 researchers, 7,110 technicians and 7,919 support staff. Approximately 70% of these people are employed by the government. A closer look at Thailand’s 2005 current account data for expenditure on foreign intellectual property rights reveals that Thailand paid a total of 67.167 billion baht to foreign countries in royalties and license fees, but received only 681 million baht from such fees. These figures are evidence of the fact that Thailand has a somewhat low level of technological invention and research because different forms of technology are depended by importing from developed countries. This also reflects the imbalance Thailand faces in terms of the royalties and license fees the country has to incur. These fees have increased dramatically in recent years, from 28.308 billion baht in 2000 to approximately 67.167 billion in 2005 and are liable to continue increasing each year20. Although Thai business operators might possess considerable less R&D than other developed countries, they continue to conduct R&D in a variety of forms that increases annually as can be observed from the number of applications for intellectual asset registration. Categorization of each type reveals that “Trademarks” are the most commonly registered intellectual asset wherein a total of 122,631 trademarks were registered in Thailand from 1999 to the first quarter of 2005, which can be categorized into 72,829 items (59.4 percent) registered by Thais and 49,802 items (40.6 percent) registered by foreigners in Thailand. Therefore, it is evident that Thais register only a few more intellectual assets in Thailand than foreigners. 20 Royalties and license fees refers to revenue (export) and expenditure (import) of residents and non-residents for permission to use intangible assets and non-financial assets, including permission to use original items, such as technical trademarks and design rights in the production and franchise, distribution of original documents and films produced in accordance with the copyright agreement, etc. 10 Figure 1: Royalties and license fees received from and paid to foreign countries by Thailand Million Baht 70,000 67,167 63,732 Royalties and License Fees by Thailand Received from Foreign Countries 60,000 Royalties and License Fees Paid by Thailand to Foreign Countries 52,734 50,000 47,427 40,000 35,507 28,308 30,000 24,857 22,064 21,339 20,000 15,691 10,806 18,169 11,364 10,000 0 67 103 115 637 1993 1994 1995 1996 1,214 1997 292 729 336 393 317 313 574 681 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 Source: Bank of Thailand Table 3: Numbers of IPR Registrations Compared between Thais and Foreigners Types of IPRs Thais Trademark Percent Invention Patent Percent Design Patent Percent Petty Patent Percent 72,829 (59.4) 291 (6.4) 2,859 (52.9) 1,672 (93.3) Foreigners 49,802 (40.6) 4,257 (93.6) 2,540 (47.1) 120 (6.7) Total 122,631 (100) 4,548 (100) 5,399 (100) 1,792 (100) Source: Thailand’s Department of Intellectual Property Right Note: 1) January 1999-March 2005 for Trademark, Invention Patent, and Design Patent 2) January 1999-December 2005 for Petty Patent 11 Consideration of the number of invention patent registrations in Thailand reveals that approximately 93.6 percent are registrations by foreigners while more than 93.3 percent of the petty patent registrations were filed by Thais. The reason for the aforementioned differences is likely to be due to the fact that most Thai inventors continue to lack sufficiently advanced inventions for registration as invention patents and are more suitably registered as petty patents because petty patent registrations do not require high levels of advancement, but call only for the inventions to be new. As for design patents, we find that only a few more Thai apply for registration than foreigners. Of a total of 5,399 items registered, 2,859 items (52.9 percent) were registered by Thais and 2,540 items (47.1 percent) were registered by foreigners. In conclusion, this section reviews how SMEs manage intellectual property and why they do not value the importance of registering for intellectual property. The next section provides further detail from data that was collected through an in-depth interview with Thai SME entrepreneurs about their decisions to register their IPRs. The cost-benefit comparison will be analyzed based on out in-depth interview’s results. IV. Qualitative Assessment: A Cost-Benefit Comparison We collect a number of in-depth interviews with the Thai entrepreneurs classified by three industries, since these three industries are largely involved with creations of the mind including invention patents, design patents and petty patents. 1. Handicrafts and original products 2. Certain One-Tambon-One-Product (OTOP) goods 3. Furniture and home decoration Moreover, certain OTOP products are associated with other forms of intellectual property beyond patents. Examples that may be cited include local wisdom and geographical indication of sources21. The data then will be assessed through cost-benefit analysis. In order to clarify why the Thai SME do not register intellectual property, our analysis is categorized by cost perspective and benefit perspective as follow: 4.1. Cost Analysis In respect to cost analysis, it is found that some of the entrepreneurs feel that hiring the service of lawyers produces excessive cost leading small business entrepreneurs to be deterred from legal consultancy and not to register their intellectual property According to the initial explanation, there are two types of cost accompanying with intellectual property registration: Financial cost and Non-financial cost 21 OTOP is a brand of product under One Tambon One Product Project, a nationwide sustainable development initiative launched by the Thai government in 2001. It aims to promote the unique products made by a local communities (called Tambon in Thailand), by utilizing their indigenous skills and craftsmanship combined with available natural resources and raw materials. The Thai government provides communities with assistance with regard to product development and market access in a global arena. 12 The interview shows that each entrepreneur weights these two costs differently depending on the types of product and nature of business. Usually, what has been taken into account is the average cost analysis. Provided that the business enterprises have low sale figure, the financial cost will be weighted heavily. On the other hand, for those that operate on trend and fashion, the non-financial (such as time) assumes precedence over the financial cost. Another reason that links with a denial to intellectual property registration is the length of time that the overall process might take. With a limited number of personnel to carry out checks and deal with the issue, the entrepreneurs relinquish their attempt to register the intellectual property based on a perception that the invented patterns and innovation will have already been infringed by the time they are transformed into the right holders. We interviewed authorities involved in the intellectual property registration and discovered that the duration from patenting to issuing legal authorization will take at least 19 months. Nevertheless, after analyzing the benefits of registering the intellectual property, we discovered that a majority of SME entrepreneurs pay attention to the profit in terms of marketing and market access, rather than the exploitation of intellectual property. Lower level of importance is assigned to the merit of innovation and invention. In the entrepreneurs’ view, marketing will improve sales and profit whereas design and innovation will have little direct impact to the business. Beyond that, small enterprises often face the difficulties in reaching capital funds. The restriction profoundly affects the entrepreneurs’ ability to expand their business and invest into new technology. Apart from this, Thai entrepreneurs do not appreciate government initiatives in intellectual property and support. Rather, small-sized enterprises prioritize marketing and market penetration as the matters of immediate need. In addition, according to the in-depth interview, a majority of the sampled entrepreneurs have not registered a patent for a variety of reasons. There are certain limitations with the products themselves; the quality may not satisfy the standards prescribed by the Intellectual Property Department of Thailand. Or, in other cases, the entrepreneurs are devoid of trust in legal protection of intellectual property. A scarcity of information and government education constitutes public misunderstanding in government proceedings and self-registration 4.2. Benefits Analysis First and foremost, creative products are easily to be adapted. In other words, registered innovation and patterns are not unlikely to be copied. Judicial litigation of intellectual infringement undergoes a long period of inspection and might not even help in such circumstances. In addition, some entrepreneurs juxtapose the concept of intellectual property with public possession. The inventors are unconditionally willing to transfer their knowledge to others in community. The idea is congruent with the sharing culture of Thai society, whereby intellectual property is perceived as community rather than individual asset The entrepreneurs do not recognize the value of intellectual property. Even with such recognition, SME entrepreneurs usually perceive that a public register entails a disclosure of manufacturing procedures, which is what the entrepreneurs are unwilling to do. In addition, the entrepreneurs do not trust the effectiveness of legal protection. According to those who have applied for a public register, there exists a gap in legal protection of intellectual property with a possibility that their products are subjected to copy and adaptation. A slight manipulation of registered products is not counted as an infringement by law. 13 The entrepreneurs lack the understanding in legal protection of intellectual property, proper advice and education from government agencies. An application for public transfer and expenditures on legal consultants may elevate the operational cost especially for SMEs as newly established businesses. SME entrepreneurs, therefore, have to consider the competing alternatives between the revenue that the companies might be deprived due to future imitation and the financial and non-financial cost vested in intellectual property registration. In this perspective, the entrepreneurs may hesitate to take action, but adopt other indirect alternatives to protect intellectual property. For instance, essential information is kept as secret within industry household. A majority of SMEs are concentrated on product design and embrace design, rather than invention patents. Others explain that registration process consumes a long period of time. Under the Department of Intellectual Property, the authorities have to undertake a careful consideration, which results in the out datedness of products even before the approval is notified. Despite the approval, benefits of public register are not visible. Apart from that certain entrepreneurs have a strong belief that their products are intertwined with sophisticated skills and manufacturing process. SME entrepreneurs are committed to made-to-order production without a requirement to be creative and constructive. A public register of patterns and design is treated as redundant. Certain SME entrepreneurs do have an intention to register for patents. But, there products are not subsumed under intellectual property or fall behind the criteria. With the above restrictions, the entrepreneurs in some cases choose to register for a standard in respect of local wisdom and subsequently develop their products into higher quality with unique patterns and designs. However, a decision to register their products is determined by whether the enterprises receive government advice upon the issue. Those who undertake registration regard intellectual property as critical component in establishing competitiveness in foreign and international market. Copy and imitation provokes detrimental effects to the business. Cases might arise in terms of sale reduction or a public register of the copies. Within the circumstance, original inventors could be transverse into a perpetrator of intellectual property. In conclusion, once the cost and benefits are analyzed and rated, we discovered that, in the entrepreneurs’ view, “benefits from registering are not worth the cost”. The cost is manifested as financial cost associated with the products and other resources required for learning about the registration procedures. Furthermore, a lag time between registration and authorization is interpreted as equivalent to cost that hampers the business from acquiring further market share. Based on the findings, policy recommendation proposed here will touch upon strategic management of intellectual property, how to drive performance at a policy level, and the role of other agencies relevant to SME intellectual property. V. Policy Recommendations and Conclusion Intellectual property policy performs a significant role in driving macro economy through an increase of commercial assets and micro economy through business capacity building. However, intellectual property protection yields both positive and negative impacts on society as 14 previously discussed. Intellectual property should therefore be formalized with due regard to optimal balance and fair competition within the national economic and social context. National public policy on intellectual property National Public policy on intellectual property should be boiled down into four key aspects 1. 2. 3. 4. IPR Protection IPR Enforcement Innovation Commercialization of IPR In general, Thai IPR policy focuses merely on the first and second. IPR protection is enacted by means of law and legal enforcement, but neglects the last three aspects (Item3-4). For the whole IPR system to work, all of these 4 keys must by “balanced” with the consistently supported with financial incentives. Therefore, in this regard, we deem it expedient to propose the following policy recommendations: First, Thai government should be emphasized that the Thai IPR protection must be congruent with global standard. However, the policy and measures should undergo an incremental change in relation to the level of national development: As a member country, Thailand should support intellectual property protection under the mandate of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), and benefit-sharing regulations under TRIPS Agreement. However, in the bilateral Free Trade Agreement between Thailand and the United States, Thailand is demanded to exert a higher level of protection beyond what has been listed in TRIPS22. The so-called TRIP-Plus requires an extension of IPR protection from 50 to 70 years. Stiffened IPR protection especially in pharmaceutical products might soaringly increase production cost and, thus, affect a majority of patients and their families. In this sense, IPR protection must be compatible with the level of national development. Excessive protection might slacken economic growth and end up with negative impact. In principle, Thailand as a developing country had better assert TRIPS standard. Tighter level of protection beyond TRIPS has to be satisfactorily proved that long-termed benefits will fall on Thai entrepreneurs at a macro level. Second, the Thai government should aim to enhance investment potentialities in intellectual property and innovation, as well as the commercialization of the property. Despite an increase of R&D, the investment of Thailand in R&D is still lag behind other developed countries. The government should establish an incentive for intellectual property and invention. In action, research and development should be set forth as a national agenda and incorporated into the National Economic and Social Development plan, as well as other related government strategies. Incentives may be either monetary or non-monetary. In non-monetary incentives, invention and intellectual property may be calculated as a component in Key Performance Indicator (KPI) of an organization or a petition for academic title. In the private sector, an inventor should be credited with tax incentives and marketing support. Government however had better generate social, rather than private returns through reasonable period of IPR protection and public-private transfer of knowledge. 22 Among all the countries, the US is known for its most-tightened IPR protection 15 Third, Thai government should aims to foster linkage between government intellectual property and the exploitation of such property under a business sector. Owing to the fact that research, development and intellectual property usually take place in government sector, the government might consider the demand-pull initiatives to fill the missing link between public and private arena. The initiatives include budget allocation to research institutes and public universities on their contribution to knowledge transfer. Tax incentives may be introduced to private agents that take part in IPR investment. Figure 2: Four Key Aspects of Intellectual Property Right System IPR Protection Commercialization IPR Enforcement Innovation 5.2 Policy Recommendations for Thai SMEs According to the present research, SMEs have encountered challenges in IPR management. Key issues of concern are the lack of IPR manpower, R&D personnel and awareness of intellectual property value. Amidst competitive environment today, invention and exploitation determine the competitiveness of Thai SMEs. As the responsible agencies, Small and Medium Size Enterprise Agency in cooperation with the Department of Intellectual Property should take charge in leading to the direction through the following: First, Thai government should encourage SMEs more awareness and understanding of intellectual property. Most of the Thai SMEs adopt moderate-level technology. Those that rely on high technology do not have the well-grounded understanding of IPR legal protection. Some do not apply for patent, while others disclose their innovation to the public before patent registration. SME Agency’s can assist the Department of Intellectual Property in documenting and publishing handbooks on IPR implementation for SMEs. Education may be promoted along with awareness campaign, explanation of facts with an emphasis on how intellectual property could be transformed into capital asset, and training on customer evaluation. The evaluation helps companies align production activities with customer demands and obtain the utmost value from their R&D efforts. 16 Second, Thai government should identify the scope of support. To create the intellectual property, the entrepreneurs require an extensive amount of capital, time and intensive labor skills. It is hence not surprising that research-based enterprises are among those that exceed SME requirement with respect to the number of employment. Small and Medium Size Enterprise Agency might consider extending their support to IPR industry that do not fit into the official definition of SMEs, especially the ones that tackle with value-added intellectual products. Third, Thai government should encourage SMEs to register and preserve their rights. Compared to design and petty patents, invention patents and preservation of rights demand much higher registration fee. In compatible with international trade agreement, the paper would call for government subsidy in patent registration and preservation of rights. In America, independent inventors, small-sized enterprises and non-profit organization are subject to acquire 50 percent deducted registration fee. Similar examples can also be drawn from Canada with the same 50 percent deduction basis for SMEs. Thai SMEs should cooperate with relevant agencies in launching intellectual property education ranging from patent and trademark registration to intellectual property rights. The entrepreneurs are recommended to use legal software of high quality and reasonable price including open source software. Forth, Thai government should increasing efficiency in patent checking. Patent checking should be conducted in consistent with the definition of subjects entitled to patent protection under Article 5 of the 1979 Patent Act. Nevertheless, a rigid checking system is the doubleedged sword in that it might reduce the number of unqualified application, but at the same time hamper new products from entering into the market. A panel of committees consisting of experts from government and higher educational institutions should compile a patent-checking guideline with a clear identification of subjects entitled to patent registration. Special task force may be set up to undertake the patent checking in the fields that highly affect public safety and wellbeing, such as medicine. At last, Thai government should increase the number of IPR personnel and payment. Quality of services in long term is dependent on the capacity of IPR personnel, especially those who perform patent checking. At the present, there are only 26 government officials and temporary employees who deal with the checking. The ratio of patent registration requests to the number of IPR personnel suggests concentrated workload situation with 322 requests per staff in 2002, while there are 81 and 86 requests per staff in USPTO and EPO respectively. The Department of Intellectual Property, thus, has to consider increasing patent-checking officers, especially in the fields where registration number is high. Moreover, to retain the IPR personnel and experts, payment should be restructured in accordance with the standard of private companies. Since patent checking requires special skills and expertise, comparatively low level of payment in government units might result in staff turnover. Generally, The Department of Export Promotion is entrusted with the duty to promote and expand the market for small and medium-sized enterprises by penetrating into new markets, organizing road show, seminars and training, as well as distributing news and useful information. To prevent intellectual property infringement abroad, the Department of Export Promotion in cooperation with the Department of Export Promotion should provide education and assistance in filing international patent application. This will also help in creating additional value and advancing competitiveness of Thai entrepreneurs in international market. In conclusion, intellectual property is a main driver of Thai economy. However, without sufficient information, financial resources and personnel, SME products and inventions can only take place in forms of design patents, petty patents and other trivial creations. SMEs, as a result, 17 may fail to reap desirable benefits and neglect the commercialization value of intellectual property. It is recommended that the Department of Intellectual Property, the Small and Medium Size Enterprise Agency as well as other relevant policymaking units should collaborate in segmenting the market and identifying appropriate strategic path with an emphasis on efficiency, incentives and innovation to invoke value-added and product differentiation. Table 4: The number of patent-checking officers in 2005 Countries JPO Thailand EPO USPTO Number of Requests 480,926 7,726 271,596 284,077 Number of patent-checking officers 1,105 24 3,157 3,489 Number of requests per officer 435.23 321.92 86.03 81.42 Source: Thailand’s Department of Intellectual Property, Ministry of Commerce. References Cohen, W. (1995) ‘Empirical studies of innovative activity’ in P. Stoneman (Ed.) Handbook of the Economics of Innovation and Technological Change. Oxford, Blackwell. Gambardella, A. (1995) Science and Innovation: The U.S. Pharmaceutical Industry During the 1980s. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Geroski, P. (1994) Market Structure, Corporate Performance and Innovative Activity. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Gruber, H. (1992) ' Persistence of leadership in product innovation' , Journal of Industrial Economics, Vol 40, No 4, pp.359-375. Gruber, H. (1995) ' Market structure, learning and product innovation: The EPROM market' , The International Journal of the Economics of Business, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp.87-101. Moore, B. (1996) “Sources of Innovation, Technology Transfer, and Diffusion” in A. Cosh and A. Hughes (eds) The Changing State of British Enterprise, ESRI Centre of Business Research, Cambridge. Pholphirul, P. (2005) Competitiveness, Income Distribution, and Growth in Thailand: What Does the Long Run Evidence Show?, Research Paper No. I24, Bangkok: Thailand Development Research Institute. Poltorak, A.I. and Lerner, P.J. (2002) Essentials of Intellectual Property, New York: John Wiley & Sons. Schumpeter, J (1942) Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy. London: Routledge (1992 version). 18 Scherer, F.M. (1992) ‘Schumpeter and Plausible Capitalism’ Journal of Economic Literature Vol. 30, pp.1416-1433. Sutton, J. (1998) Technology and market structure: Theory and history. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. Symeonidis, G. (1996) ‘Innovation, Firm Size and Market Structure: Schumpeterian Hypotheses and Some New Themes’ OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 161. Symeonidis, G. (2002). The Effects of Competition: Cartel Policy and the Evolution of Strategy and Structure in British Industry. Harvard, MIT Press. Valimaki, M. (2002) “Strategic Use of Intellectual Property Rights in Digital Economy: Case of Software Markets”, Finland: Helsinki Institute for Information Technology, mimeo. Vandewege, W (2003) The Sustainability of Copyright, Science Policy Research, University of Sussex, United Kingdom: Sussex. 19

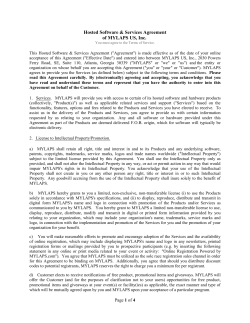

© Copyright 2025