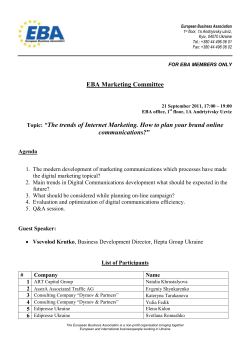

Why the EU keeps its door half – open for...