PROOF COVER SHEET

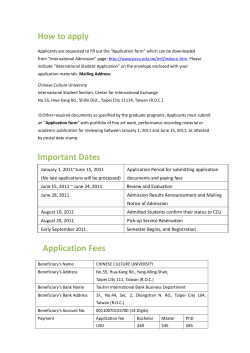

RJAP_A_694711 style2.cls (JAP) May 31, 2012 21:12 PROOF COVER SHEET Author(s): Tony Cavoli, Victor Pontines, and Ramkishen S. Rajan Article title: Managed floating by stealth: the case of Taiwan Article no: 694711 Enclosures: 1) Query sheet 2) Article proofs Dear Author, 1. Please check these proofs carefully. It is the responsibility of the corresponding author to check these and approve or amend them. A second proof is not normally provided. Taylor & Francis cannot be held responsible for uncorrected errors, even if introduced during the production process. Once your corrections have been added to the article, it will be considered ready for publication. Please limit changes at this stage to the correction of errors. You should not make insignificant changes, improve prose style, add new material, or delete existing material at this stage. Making a large number of small, non-essential corrections can lead to errors being introduced. We therefore reserve the right not to make such corrections. For detailed guidance on how to check your proofs, please see http://journalauthors.tandf.co.uk/production/checkingproofs.asp. 2. Please review the table of contributors below and confirm that the first and last names are structured correctly and that the authors are listed in the correct order of contribution. This check is to ensure that your name will appear correctly online and when the article is indexed. Sequence Prefix Given name(s) Surname 1 Tony Cavoli 2 Victor Pontines 3 Ramkishen S. Rajan 0 Suffix RJAP_A_694711 style2.cls (JAP) May 31, 2012 21:12 Queries are marked in the margins of the proofs. AUTHOR QUERIES General query: You have warranted that you have secured the necessary written permission from the appropriate copyright owner for the reproduction of any text, illustration, or other material in your article. (Please see http://journalauthors.tandf.co.uk/preparation/permission.asp.) Please check that any required acknowledgements have been included to reflect this. Q1. Au: Please check if authors’ affiliations are ok as set and also provide City, State, Country names for affiliation [c]. Q2. Au: Ref. “Ouyang and Rajan 2000” has been changed to “Ouyang and Rajan 2009”. Please check. ¨ Q3. Au: Please provide publisher’s name and location in ref. “Bubula and Otker-Robe, 2002”. Q4. Au: Please provide volume no. for “Cavoli and Rajan, 2008”. Q5. Au: Please provide location of publisher in ref. “Cavoli and Rajan, 2009”. Q6. Au: Please provide complete ref. details for “Cavoli and Rajan, 2010”. Q7. Au: Please provide page range in ref. “Frankel and Wei, 1994”. Q8. Au: Please provide location of publisher in ref. “Ghosh et al. 1995”. Q9. Au: Please provide page range in ref. “Glick et al. 1999”. Q10. Au: Please provide location of publisher in ref. “IMF, 1997”. Q11. Au: Please provide publisher’s name and location in ref. “Levy-Yeyati et al. 2007”. Q12. Au: Please update page range and volume no. in ref. “Ouyang and Rajan, 2009”. Q13. Au: Please provide publisher’s name and location in ref. “Pontines et al., 2010”. Q14. Au: Please cite ref. “Rajan, 2009” in the text. Q15. Au: Please provide missing volume no. in ref. “Srinivasan et al., 2008”. Q16. Au: Please cite ref. “Subramanian, 2010” in the text. 0 RJAP_A_694711 style2.cls (JAP) May 31, 2012 21:12 How to make corrections to your proofs using Adobe Acrobat Taylor & Francis now offer you a choice of options to help you make corrections to your proofs. Your PDF proof file has been enabled so that you can edit the proof directly using Adobe Acrobat. This is the simplest and best way for you to ensure that your corrections will be incorporated. If you wish to do this, please follow these instructions: 1. Save the file to your hard disk. 2. Check which version of Adobe Acrobat you have on your computer. You can do this by clicking on the “Help” tab, and then “About.” If Adobe Reader is not installed, you can get the latest version free from http://get.adobe.com/reader/. • If you have Adobe Reader 8 (or a later version), go to “Tools”/ “Comments & Markup”/ “Show Comments & Markup.” • If you have Acrobat Professional 7, go to “Tools”/ “Commenting”/ “Show Commenting Toolbar.” 3. Click “Text Edits.” You can then select any text and delete it, replace it, or insert new text as you need to. If you need to include new sections of text, it is also possible to add a comment to the proofs. To do this, use the Sticky Note tool in the task bar. Please also see our FAQs here: http://journalauthors.tandf.co.uk/production/index.asp. 4. Make sure that you save the file when you close the document before uploading it to CATS using the “Upload File” button on the online correction form. A full list of the comments and edits you have made can be viewed by clicking on the “Comments” tab in the bottom left-hand corner of the PDF. If you prefer, you can make your corrections using the CATS online correction form. 0 RJAP_A_694711 style2.cls (JAP) May 31, 2012 21:12 CE: RKM QA: APJ Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy Vol. 17, No. 3, August 2012, 514–526 Managed floating by stealth: the case of Taiwan Tony Cavoli,a∗ Victor Pontinesb,c and Ramkishen S. Rajand,e a 5 Q1 School of Commerce and Centre for Asian Business, University of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia; bFlinders Business School, Flinders University, Adelaide, Australia; cThe Southeast Asian Central Banks (SEACEN) Research and Training Centre; dLKY School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore; eSchool of Public Policy, George Mason University, Virginia, USA Taiwan is among the world’s largest holders of international reserves, having accumulated US $350 billion of foreign exchange as of end 2009. Despite its significance, since it is not a member of the IMF, Taiwan has been relatively under-studied compared to many of its other Asian counterparts. As such, the aim of this paper is to shed a little light on Taiwan’s exchange rate policies and strategies. Our results reveal a regime that can be characterized as involving some degree of management of the New Taiwanese dollar (NTD). More significantly, we can confirm the existence of an asymmetry in central bank foreign exchange intervention responses to currency appreciations versus depreciations in Taiwan, particularly in the case of nominal effective exchange rates (NEERs). This in turn rationalizes the relative exchange rate stability as well as the sustained reserve accumulation in Taiwan. 10 15 Keywords: exchange rates; foreign exchange intervention; reaction function; reserves; Taiwan 20 JEL classifications: F31, F33, F40 1. Introduction A number of high-growth Asian economies have adopted a variety of intermediate regimes (currency baskets, crawling bands, adjustable pegs and such). Two notable ones about 25 which much has been written in recent times have been India and Singapore. According to the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), India ‘monitors and manages the exchange rates with flexibility without a fixed target or a pre-announced target or a band, coupled with the ability to intervene if and when necessary’. Singapore officially manages its currency against a basket of currencies, with the trade-weighted exchange rate used as an intermediate target 30 to ensure that the inflation target is attained.1 While Singapore’s currency basket regime follows a more strategic orientation, both China and Malaysia in July 2005 officially shifted to what may be best referred to as a more mechanical version of a currency basket regime (i.e. keeping the trade-weighted exchange rate within a certain band as a goal in and of itself) where currency stability appears to be of first-order concern. In Singapore, by 35 contrast, currency stability is important in the attainment of an inflation objective. Another economy that many have argued is a managed floater and a relatively successful one at that is Taiwan. Despite this, Taiwan’s central bank, the Central Bank of China (CBC), ∗ Corresponding author. Email: tony.cavoli@unisa.edu.au ISSN: 1354-7860 print / 1469-9648 online C 2012 Taylor & Francis http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13547860.2012.694711 http://www.tandfonline.com RJAP_A_694711 style2.cls (JAP) May 31, 2012 21:12 Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy 515 B/w in print, colour online Figure 1. International reserve accumulation in Taiwan (excluding gold), 1995:q1–2009:q2 (US$ millions). Note: Data for 2009 are up to 2009:m9. Source: CEIC database and CBC. characterizes the exchange rate as follows: ‘Following the establishment of the Taipei Foreign Exchange Market in February 1979, a flexible exchange rate system was formally implemented. Since then, the NT dollar exchange rate has been determined by the market. However, when the market is disrupted by seasonal or irregular factors, the Bank will step in’.2 Clearly, the CBC has been doing more than just intermittent intervention to smooth out fluctuations as evident from the massive reserve build-up (Figures 1 and 2). In fact Taiwan is among the world’s largest holders of international reserves, having accumulated US $350 billion of foreign exchange as of end 2005. Despite its significance, not being a member of the IMF, Taiwan has been relatively under-studied compared to many of its other Asian counterparts. The aim of this paper is to shed a little light on Taiwan’s exchange rate policies and strategies. The paper is organized as follows. The next section presents, by way of context, a brief discussion of the measurement of de jure exchange rate regimes. The underlying difference between de jure regimes and the de facto regimes (two such measures are employed in this B/w in print, colour online Figure 2. NTD exchange rate (bilateral per USD and nominal effective exchange rate), 2000:m1–2009:m9. Source: BIS and CBC. 40 45 50 RJAP_A_694711 style2.cls (JAP) 516 55 60 65 70 75 85 90 95 21:12 T. Cavoli et al. paper) is that the former relies on central banks’ claims and statements, while the latter attempts to uncover the revealed preferences of central banks through models and data. Section 3 offers a simple estimation of the degree of influence of the G3 currencies on the New Taiwanese dollar (NTD) to understand the degree of exchange rate flexibility over the last decade. To preview the main conclusion, although there are signs of gradual movement toward somewhat greater exchange rate flexibility in many of the regional countries, the propensity for foreign exchange intervention and exchange rate management remains fairly high, particularly in terms of managing against a currency basket. So does there still exist a ‘fear of floating’ in Taiwan a la Calvo and Reinhart (2002)? The sustained stockpiling of reserves in Taiwan since 2000 suggests that it is more sensitive to exchange rate appreciations than to depreciations. Section 4 explores in more depth this particular issue of asymmetry in exchange rate intervention in Taiwan through a simple model of optimal central bank behavior which derives a simple central bank intervention reaction function. The results suggest the existence of an asymmetry in central bank foreign exchange intervention responses to currency appreciations versus depreciations especially for nominal effective exchange rates (NEERs). This in many respects rationalizes the relative exchange rate stability as well as the sustained reserve accumulation in Taiwan. It is crucial to point out at here that the reason for choosing two methods of measuring de facto regime choice is because no single measure is able to capture the essential characteristics of a currency regime. By employing more than one measure at least enables us to assess regimes across multiple dimensions – thereby allowing a richer set of policy conclusions to be drawn. Section 5 concludes the paper with a discussion of the macroeconomic challenges facing a small and open economy like Taiwan. 2. 80 May 31, 2012 De jure exchange rate regimes and the IMF classification As mentioned above, the basic difference between de jure regimes and the de facto regimes is that the former relies on central banks’ claims and statements, while the latter uses many and various methods to attempt to uncover the underlying behavior of central banks. Until 1998 it was fairly easy to obtain de jure exchange rate classifications as these data were compiled from national sources by the IMF. Specifically, between 1975 and 1998 the IMF’s Annual Report on Exchange Arrangements and Exchange Restrictions was based on self-reporting of national policies by various governments with revisions in 1977 and 1982. Since 1998 – and in response to criticisms that there can be significant divergences between de facto and de jure policies – the IMF’s exchange rate classification methodology has shifted to compiling unofficial policies of countries as determined by Fund staff.3 While the change in IMF exchange rate coding is welcome for many reasons (including the fact that the new set of categories is more detailed than the older one), the IMF is no longer compiling the de jure regimes. The way that this is typically done is by referring to the website of each central bank or other national sources individually and wading through relevant materials.4 As noted, the IMF has replaced its compilation of the de jure exchange rate regimes with the behavioral classification of exchange rates. The new IMF coding is based on various sources, including information from IMF staff, press reports, other relevant papers, as well as the behavior of bilateral nominal exchange rates and reserves.5 In the sections that follow, we employ two methods of establishing the de facto regime for Taiwan. The first is based on combining two commonly used techniques, the regression of the local currency RJAP_A_694711 style2.cls (JAP) May 31, 2012 21:12 Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy 517 on major currencies and a simplified application of exchange market pressure as measured by an intervention index.6 The second method uses a central bank loss function to make 100 inferences more directly about central bank behavior in order to uncover the possibilities of asymmetries. 3. Degree of influence of G3 currencies on the NTD Recognizing that there may be a discrepancy between the de facto and de jure exchange rate regimes, this section presents an analysis of the degree of de facto exchange rate 105 flexibility of the NTD. To this end, this section outlines a measure that has been recently used in Frankel and Wei (2007) as a way of incorporating exchange rate regime flexibility (or fixity) into the original Frankel–Wei methodology (Frankel and Wei 1994). Basically, Frankel and Wei (1994) present a regression of the local currency on a number of major currencies as a way of inferring implicit basket weights for the local currency. The method 110 presents a very simple way of establishing the connection between a local currency and the major ones. This measure, however, reveals very little about the underlying flexibility (or conversely, fixity) of the local currency. Frankel and Wei (2007) find a simple solution by specifying a simple flexibility term. 115 Consider the following: Intervention Index = e + r,7 (1) where e is defined as the local currency per some independent numeraire – here we use the SDR8, and r is the monthly change in international reserves less gold.9 The index itself is supposed to be representative of the degree of exchange market pressure. If the exchange rate floats then e is high relative to r. However, under managed exchange rate regimes, exchange market pressure is maintained through r being relatively higher by 120 virtue of the manipulation of foreign reserves by central banks to keep the exchange rate stable. To see how it relates to the choice of exchange rate regime, we need to now use the Intervention Index to augment the original Frankel–Wei method as follows: et = α0 + α1 US t + α2 JPt + α3 EU t + γ Intervention Index + µt . (2) The α coefficients in Equation (2) are often interpreted as implicit currency weights. The 125 G3 currencies of USD, euro and the yen (all per the SDR) are chosen as they represent world currencies deemed to exert sufficient influence on the local currency such that it is worthy of consideration in our estimates. It is tempting to also include other currencies that may influence the NTD, such as the Singapore dollar, the Yuan and the Indian Rupee. However, these currencies are highly correlated with the USD (see Cavoli and Rajan 2009), 130 their inclusion will result in high levels of multicollinearity in the model and will also present difficulties in interpreting the coefficient values. Furthermore, while it is tempting to interpret these coefficients as potential basket weights, it is probably more prudent for them to be interpreted as ‘degrees of influence’. The reason for this is that it is very difficult to say whether a high and significant coefficient value implies a basket currency, or merely 135 market-driven correlations.10 We turn now to the coefficient for Intervention Index, γ . As γ → 1, the exchange rate per local currency becomes more flexible as Equation (2) converges to the dependent RJAP_A_694711 style2.cls (JAP) 518 May 31, 2012 21:12 T. Cavoli et al. variable and e and the α coefficients should be close to zero and/or statistically insignificant. As γ → 0, the exchange rate becomes more fixed as the situation where reserve movements overshadow exchange rate movements is reflective of a sustained exchange rate intervention, and the extent of fixity to various major currencies is captured by the α coefficients.11,12 We use monthly data for the period for two sample periods. The first is the period 145 2000:m3–2009:m9 and the second is truncated at 2000m3–2007m12. The reason is to ascertain whether there is any material difference in the results if one excludes the global crisis period (broadly defined as 2008–2009). Keep in mind that reserve values could change because of currency fluctuations.13 Ideally, we should exclude these effects before estimation but are not able to do so since we lack data on the currency composition of 150 reserves. This may impact the precision of the results in some cases. 140 3.1. Static estimates of the degree of influence on the NTD Equation (2) is estimated using OLS and we take an autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) approach to the estimation to soak up any as much serial correlation and omitted variable bias as we can. Table 1 presents the results. The USD coefficient is an important variable as 155 it reveals something about the degree of influence of that currency on the NTD. We can see that the degree of influence, although highly significant statistically, is reasonably low at around 0.45 and 0.49 for the full sample and truncated sample, respectively. Those countries known to peg closely to the USD return figures much closer to unity for this coefficient (Cavoli and Rajan 2010). The interpretation there is that the USD is the predominant, 160 and for the most part, the only currency to influence the local currency, thus presenting considerable evidence of the existence of a USD peg. Further, those countries known to have more flexible regimes tend to return coefficients that are often less statistically significant – suggestive of greater noise around the movement of the local currency in response to movements in the world currencies (see Cavoli and Rajan 2010). From Table 1, it can also 165 be seen that in the case of Taiwan that there is no evidence to suggest that the euro or yen have any material influence on the NTD in the sample periods reported though we should make the point that the yen coefficient is almost significant at the 10% level (11%) and the euro is less statistically insignificant when the crisis period is included in the sample. We Table 1. Degree of influence of G3 currencies for Taiwan. Const USD Yen Euro Intervention Index Adj R2 DW Sample Taiwan 1 Taiwan 2 −0.32 (0.001) 0.45 (0.00) 0.06 (0.11) 0.04 (0.48) 0.10 (0.00) 0.52 1.45 99m3:09m9 −0.30 (0.005) 0.49 (0.00) 0.08 (0.19) 0.002 (0.97) 0.10 (0.00) 0.53 1.49 99m3:07m12 Note: Dependent variable: NTD per SDR. Figures in parentheses are p-values (generated using Newey–West robust standard errors) and those parameters significant at 10% or better are in bold. The full sample is 1999m3–2009m9. Any deviation from this reflects the availability of data at the time of its acquisition. A one-month lagged dependent variable is included in all regressions and a one-month lag term for the USD per SDR if its inclusion helps to reduce serial correlation. Source: Authors. RJAP_A_694711 style2.cls (JAP) May 31, 2012 21:12 Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy 519 conjecture here that the crisis period may have increased the extent of influence of both the 170 yen and euro on the TWD, but this effect is not strong. The Intervention index is also highly statistically significant and while the coefficient value (0.10) appears low, it is actually quite high in comparison with many Asian countries (see Cavoli and Rajan 2010) but not high enough to categorically suggest a flexible exchange rate regime. What appears to be the case here is that Taiwan allowed relatively greater exchange rate flexibility in the NTD than has been observed in other countries in the region 175 (even if by a small margin). As mentioned above, the pertinent question here is to what extent are these weights market-driven versus policy targets? We can attempt to answer this by summarizing the interaction between the currency weights and the Intervention index. Taiwan has reasonably low and statistically significant Intervention indices coupled with lower (in relative terms) 180 USD weights and some positive but statistically insignificant weight to other currencies. This is indicative of some degree of management of the currency with respect to the USD but with some freedom of movement left in the system to adjust to shocks and to allow some monetary autonomy. 185 3.2. Recursive LS estimates As a further check to investigate whether there has been a change in the degree of intervention/flexibility in Taiwan over time, Figure 3 presents the recursive least squares estimates for the USD coefficient, α 1 .14 The recursive estimates are generated by running the regression for Equation (2) iteratively – beginning with k observations (usually the number of regressors, see footnote 14) and recording the coefficient values until we reach the full 190 sample as follows15: et = α0 + α1t US t + α2 JPt + α3 EU t + γt Intervention Index + µt for t = k, . . . , T , 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 B/w in print, colour online 0.2 0.1 0.0 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 Figure 3. Recursive least squares estimates for the USD weight for the NTD. Source: Authors. (3) RJAP_A_694711 style2.cls (JAP) May 31, 2012 520 21:12 T. Cavoli et al. where α 1t and γ t are the time-varying coefficients for the USD and the intervention index, respectively, and T is the full sample under consideration for each equation. They are derived by running the regressions as in Table 1 – but to avoid cluttering up the diagrams 195 and to highlight any possible influence of the recent global crisis, only the sample from 2005 is shown. At a broad level, the results reveal that there appears to be a general trend downwards in the recursive series for the USD. This is suggestive of a lowering of the degree of influence of the USD for each local currency and a possible increase in flexibility of the NTD vis-`a-vis 200 the dollar. The NTD’s USD peg declined somewhat between mid 2008 and early 2009 with the onset of the global financial crisis and reversal in capital flows (from NTD 30.5 per US$ as of end 2008 to 34.3 per US$ in first quarter of 2009). Similar results are obtained when we estimated the point estimates for the subperiod ending before the crisis.16 There appears to be no trend at all in the recursive series for the Intervention index. This is indicative 205 of a consistent policy stance, viz. reserves management. This occurs despite the lower degree of influence of the USD, suggesting the likelihood that the degree of exchange rate influence (induced by policy) to currencies other than the USD may have increased (i.e. possible management against a broader currency basket) but not to the extent that it has been emphatically picked up in the time invariant estimates in the previous section. 210 4. Asymmetry in Asian exchange rate policies The foregoing analysis makes apparent that the NTD appears to have been managed somewhat against the USD mainly but there is a possibility that, in the latter part of the sample, the NTD might be influenced increasingly against a basket of currencies. Further evidence of this is provided by Figure 4 which highlights the standard deviations of the NTD per 215 USD to be greater than the NEER. The additional fact that Taiwan has rapidly built up reserves implies that the currencies are effectively undervalued, presumably in order to sustain export-led growth. Therefore, whereas Calvo and Reinhart (2002) noted that exchange rate policy in the 1990s in emerging economies is best characterized as ‘a fear of floating’, we conjecture that like its Asian counterparts, the NTD in the 2000s can be more 220 precisely described as being a ‘fear of appreciation’. Somewhat surprisingly, there has been 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 B/w in print, colour online 0.2 0.1 0.0 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 Figure 4. Recursive least squares estimates for the Intervention Index for the NTD. Source: Authors. RJAP_A_694711 style2.cls (JAP) May 31, 2012 21:12 Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy 521 B/w in print, colour online Figure 5. Standard deviation of Taiwan’s bilateral and effective exchange rates, 2000:m1–2009:m9. Note: SD – Standard deviation. Source: Authors based on data from BIS and CBC. scant discussion of this possible asymmetry in foreign exchange market intervention in the debate of de facto exchange rate regimes (Pontines and Rajan 2010). 4.1. Central bank intervention reaction function17 We first outline a simple model of optimal central bank behavior which derives a simple central bank intervention reaction function which is our estimating equation. More for- 225 mally, the central bank is assumed to have full and direct control over a proxy measure of intervention defined as the percent changes in foreign exchange reserves (rt ). The central bank intervenes in the foreign exchange market to minimize the following intertemporal criterion18: min Et−1 (Rt ) ∞ δ τ Lt+τ , (4) τ =0 where δ is the discount factor and Lt is the period loss function. We follow Surico (2008) 230 and Srinivasan et al. (2008) in specifying the loss function in linear-exponential form: Lt = 1 λ γ (rt − r ∗ )2 + (e˜t − e∗ )2 + (e˜t − e∗ )3 , 2 2 3 (5) where λ > 0 is the relative weight and γ is the asymmetric preference parameter on exchange rate stabilization. e˜t denotes the percent change in the exchange rate (et ) (where et is the foreign currency price of one unit of domestic currency and the NEER, respectively), r∗ is the optimal level of reserves and e∗ is the central bank’s target exchange rate which is 235 assumed zero in this case. If γ > 0, deviations of the same size but opposite sign yield different losses and, thus, the rate of appreciation is weighted more heavily than the rate of depreciation, i.e. ∂Lt /∂(e˜t ) = λ[e˜t + (γ /2)(e˜t )2 ] > 0, for e˜t > 0. In other words, a rise in the exchange rate (appreciation) increases the policymaker’s loss (Figure 5). RJAP_A_694711 style2.cls (JAP) May 31, 2012 21:12 522 T. Cavoli et al. Table 2. Intervention reaction function and policy preference estimates, for Taiwan, 2000:m1– 2009:m9a,b. Row (1) Row (2) c α β γ = 2β/α J-test 0.640∗∗∗ (0.094) 1.436∗∗∗ (0.115) −0.249∗∗∗ (0.056) −0.582∗∗∗ (0.223) −0.158∗∗∗ (0.028) −0.699∗∗∗ (0.130) 1.226∗∗∗ (0.405) 2.377∗∗∗ (0.678) 14.91 15.86 Notes: aSpecification: r = c + α e˜ + β(e˜ )2 + v . t t t t bStandard errors using a four-lag Newey–West covariance matrix are reported in parentheses. Row (1) denotes that e˜t is measured using the nominal exchange rate of the USD per local currency, while Row (2) denotes that e˜t is measured using the NEER. J -test refers to the Hansen’s test of overidentifying restrictions, which is distributed as a χ 2(m) under the null hypothesis of valid overidentifying restrictions. A constant, lagged values (15 and 10 months) of rt , e˜t as well as current and lagged values (eight and nine months) of the US federal funds rate are used as instruments. Superscript ∗∗∗ denote rejection of the null hypothesis that the true coefficient is zero at the 1% significance level. The standard errors of γ are obtained using the delta method. Source: Authors. 240 It is assumed that interventions can reduce the rate of change (depreciation/appreciation) in the exchange rate. Accordingly e˜t − e∗ = a0 + a1 rt + εt , (6) where a1 > 0 and the error term, εt , is independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) with zero mean and variance σε2 . Minimizing Equation (5) by choosing rt subject to the constraint (6) leads to the following intervention reaction function of the central bank: γ rt = r ∗ − λa1 Et−1 e˜t + (e˜t )2 . 2 245 (7) Replacing the expected values with actual values, the empirical version of the intervention reaction function can be simplified as follows: rt = c + α e˜t + β(e˜t )2 + vt , (8) where α = −λa1 , β = −λa1 γ /2. The reduced form parameters [α, β] allow us to identify the asymmetric preference on exchange rate stabilization, γ . It can be shown that the asymmetric preference parameter is γ = 2β/α. This parameter is the main concern of our 250 empirical exercise in the next section (Srinivasan et al. 2008, Surico 2008). 4.2. Empirical results Our estimation is based on monthly data for the sample period between 2000:m1 and 2009:m9. The variables used in the estimation are as follows: the US federal funds rate, rt = (log Reservest )∗ 100 and e˜t = (log et )∗ 100 with et being the nominal exchange rate 255 (USD per domestic currency) and the NEER, respectively, such that a rise in each of these two alternative definitions of the nominal exchange rate denotes a currency appreciation and vice versa. As noted, the data are sourced from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) and the Central Bank of Taiwan (CBC). As earlier implied, Equation (8) is the main equation of interest in the empirical test.19 260 Table 2 reports the estimates of the intervention reaction function as well as the asymmetric preference parameter. For each country, we present two sets of results – Row (1) using the RJAP_A_694711 style2.cls (JAP) May 31, 2012 21:12 Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy 523 nominal bilateral exchange rate (USD per domestic currency) and Row (2) presents those using the NEER. The J test indicates that the hypothesis of valid overidentifying restrictions is never rejected. The parameters on e˜t and α are statistically different from zero in all cases. Of primary interest to us is the parameter on the squared e˜t the β coefficient. This is because testing the restriction that H 0 : β = 0 is akin to testing H 0 : γ = 0. β is significant in all countries. What are our prior expectations of the γ (in this instance, γ is the asymmetric preference parameter)? As noted in Section 3.1, a rise in the nominal bilateral exchange rate or NEER denotes an appreciation, implying γ should be positive. Results are summarized in Table 2. The asymmetric preference parameter is significantly positive when either the nominal USD per domestic currency exchange rate or the NEER is used as the measure of the exchange rate (rise implies appreciation). This implies that the CBC appears to react differently to appreciation and depreciation pressures. More to the point, the responses of CBC to rates of appreciation are much stronger than to rates of depreciations of the same value.20 The estimated asymmetric parameter is also much higher in the case of the NEER than the nominal bilateral exchange rate for the NTD. The asymmetric preference parameter, γ , is 1.27 when the nominal bilateral exchange rate is used and almost double that at 2.38 when the NEER is used. This in turn implies that the Taiwanese central bank tends to pay more attention to managing their effective exchange rate than the USD rates. 5. Conclusion Levy-Yeyati and Sturzenegger (2007) conjectured that exchange rate policies in emerging economies have evolved toward an apparent ‘fear of floating in reverse’ or ‘fear of appreciation’, whereby interventions have been aimed at limiting appreciations rather than depreciations. Our results show a moderate degree of fixity of the NTD and confirm the existence of an asymmetry in central bank foreign exchange intervention responses to currency appreciations versus depreciations in Taiwan, particularly in the case of NEERs. This in turn rationalizes the relative exchange rate stability as well as the sustained reserve accumulation Taiwan, a conclusion that can be rationalized for many other emerging Asian economies (see Pontines and Rajan 2010). Like many other emerging Asian economies, Taiwan has experienced a surge in speculative funds in 2009. This capital inflow surge has put renewed pressures on the NTD and domestic liquidity growth. It is likely that fast-growing emerging Asian economies like Taiwan will continue to use a combination of gradual currency appreciations, foreign exchange intervention and countervailing – monetary sterilization – measures to manage domestic liquidity to minimize the risks of asset bubbles while still maintaining export competitiveness (Ouyang and Rajan 2009). However, sterilization tends to become more and more costly over time, leading many to argue that the capital inflows ought to be curtailed more directly (as opposed to merely managing their liquidity effects). Taiwan has experienced particularly intense inflows, possibly motivated by greater domestic political stability and intensified economic ties with the fast-growing Mainland Chinese economy. In response to these pressures, the Taiwanese authorities have imposed soft capital controls in the form of a ban on overseas investors from placing funds in time deposits to help counter currency speculation with a possibility of more such controls to follow if balance of payments and concomitant currency pressures become more extreme. However, going forward there are a number of reasons to allow a greater degree of exchange rate flexibility. But why? 265 270 275 280 285 290 295 Q2 300 305 RJAP_A_694711 style2.cls (JAP) 524 310 315 320 325 330 335 May 31, 2012 21:12 T. Cavoli et al. First, small and open economies like Taiwan are highly susceptible to large external shocks, such as changes in foreign interest rates, terms of trade, regional contagion effects and the like. Received theory tells us that a greater degree of exchange rate flexibility is called for in the presence of external or domestic real shocks. By acting as a safety valve, flexible exchange regimes provide a less costly adjustment mechanism by which relative prices can be altered in response to such shocks as opposed to fixed rate regimes. The latter relies on gradual reductions in relative costs through deflation and productivity increases vis-`a-vis trade partners to restore internal balance. This can prove to be prolonged and costly, as the Argentine example illustrates. Second, it is often suggested that a rigid basket peg may operate as a nominal anchor for monetary policy and be a way of introducing some degree of financial discipline domestically and breaking inflationary inertia. While there are some studies that point to such findings, they are instructive (for instance, see Ghosh et al. 1995, IMF 1997), they are by no means conclusive, as they do not account for the possibility of endogeneity of the choice of exchange rate regimes. Specifically, we cannot be sure as to whether a fixed exchange rate actually leads to lower inflation or whether countries which experience low inflation rates adopt such a regime. Glick et al. (1999) have argued that policies of pegging exchange rates in East Asia were of little benefit in terms of acting as a counterinflationary device, this goal having been attained primarily due to other factors such as relative autonomy of the monetary authorities. In their view, the use of exchange rates as nominal anchors may have actually acted as a liability as it prevented the necessary nominal currency adjustments in response to external shocks from taking place. In addition, both theory and lessons of experience with nominal anchors have shown that such pegging loses credibility over time and induces booms followed by inevitable busts and crises episodes. Pegging the exchange rate also constrains monetary independence; if unrestrained monetary policy has been a facet of the country’s past, imposing exchange rate fixity may be an advantage as it constrains the active use of monetary policy. If, however, monetary and fiscal policies have proved effective in the past, governments may be reluctant to constrain their ability to use them in the future by targeting a particular exchange rate. Acknowledgement Valuable research assistance from Sasidaran Gopalan is gratefully acknowledged. The usual disclaimer applies. 340 345 350 Notes 1. See Cavoli and Rajan (2007 , 2008) for analyses of India’s and Singapore’s exchange rate regime, respectively (also see Cavoli and Rajan 2010). 2. See http://www.cbc.gov.tw/ct.asp?xItem=856&CtNode=480&mp=2. 3. The data have since been applied retroactively to 1990. 4. See Cavoli and Rajan (2010) for some further details. ¨ 5. Also see Bubula and Otker-Robe (2002) which appears to be the intellectual basis for the IMF de facto regimes. 6. Exchange market pressure (EMP) is the most common way of measuring de facto regime choice. At its simplest, these models observe movements (first or second moment) in the exchange rates in comparison to those other variables which may act as instruments of exchange rate policy designed to limit the movement of exchange rates. Whether the currency itself, or one or more the other variables, move is referred to as ‘exchange marker pressure’. The relative activity of these variables defines whether EMP occurs due to currency movements in a flexible regime, or due RJAP_A_694711 style2.cls (JAP) May 31, 2012 21:12 Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 525 to changes in reserves or interest rates that may be being employed to keep the currency fixed. See Calvo and Reinhart (2002) and Levy-Yeyati and Struzenegger (2007) for more information. This is the same index used by Frankel and Wei. However, they use the term ‘EMP index’ as opposed to ‘Intervention index’. The use of the first term can be confusing as the index used is not the conventional EMP index commonly used in the literature. The idea behind using the SDR revolves around finding a currency that is not excessively related to any of the currencies used in this study. A common choice in this literature has been the Swiss franc, but there are concerns that its strong correlation with the euro may bias parameter estimates. Some might quibble that the SDR may be not a completely independent numeraire, however, it remains the best of all possible choices. Reserve differences are scaled by lagged domestic monetary base in order to compare the magnitude of the reserve change in relation to the stock of money base in the system. The result is an index that is more easily interpretable than if absolute values are taken. Data for Taiwan are from BIS and the central bank. It is also for this reason that we did not impose the restriction that all the currency weights should add up to one or for that matter why we do not just restrict the parameters to take values in between 0 and 1 (as there may be more complex correlations that we might know about a priori). For practical purposes, a negative coefficient should be interpreted as effectively being zero. Note that the Frankel–Wei constructed the EMP (recall, we are referring to it as the Intervention Index) so that a high correlation tells you that there is exchange rate flexibility (if r = 0 then the two exchange rates on the left and right hand sides equal each other which implies a floating exchange rate). In our sample, there is sufficient noise in the r to make the Intervention index nowhere near unity. In our estimations, we do not impose any constraints on the γ coefficient, thus it could exceed one or be negative. We prefer lower frequency data in terms of month-to-month changes as there is too much noise in high frequency data (day-to-day or month-to-month). High frequency data tend to tell us more about ad hoc interventions to minimize volatilities as opposed to degrees of influence of G3 currencies. In addition, the data on reserves are only available on a monthly basis so there is a practical dimension to our choice as well. The recursive estimates are generated by running the regression for Equation (2) iteratively – beginning with a few observations, and recording the coefficient values until we reach the full sample. Due to insufficient degrees of freedom, we discard the first 18 coefficient values. Recursive OLS is a special case of the Kalman Filter modeling strategy with time-varying coefficients. These results are typically consistent with the rolling fixed window regressions where one would drop the oldest observation before incorporating the most recent. k is the number of regressors. Due to insufficient degrees of freedom, we discard the first few coefficient values – about three years worth. Recursive OLS is a special case of the Kalman Filter modeling strategy with time-varying coefficients. These results are typically consistent with the rolling fixed window regressions where one would drop the oldest observation before incorporating the most recent. Chow Breakpoint tests were employed on the OLS estimates in Table 1 on the basis of the recursive results for the USD (Figure 3). We were especially interested from Figure 3 whether 2007m7 and 2008m7 are breaks and the results did not reject the null of no breaks for both periods. This section is based on Pontines and Rajan (2010). As was the case in the previous section, data on actual central bank intervention are not available for Taiwan. The orthogonality conditions implied by the intertemporal optimization-rational expectations paradigm make the generalized method of moments (GMM) the appropriate method of estimating Equation (7). We follow Hansen (1982) and use an optimal weighting estimate of the covariance matrix that accounts for both serial correlation and heteroscedasticity in the error terms. Hence, we report robust standard errors. For the most part, a constant, lagged values (15 and 10 months) of rt , e˜t as well as current and lagged values (eight and nine months) of the US federal funds rate are used as instruments. We have also tried the estimations for smaller subperiods, i.e. preglobal financial crisis (i.e. until early or mid 2008), and the results remain intact. 355 360 365 370 375 380 385 390 395 400 405 410 RJAP_A_694711 style2.cls (JAP) 526 May 31, 2012 21:12 T. Cavoli et al. References Q3 415 Q4 420 Q5 Q6 425 Q7 430 Q8 Q9 435 Q10 Q11 440 Q12 Q13 Q14445 Q15 Q16 ¨ Bubula, A. and Otker-Robe, I., 2002. The evolution of exchange rate regimes since 1990: evidence from de facto policies. Working Paper No.02/155, IMF. Calvo, G. and Reinhart, C., 2002. Fear of floating. Quarterly journal of economics, 117, 379–408. Cavoli, T. and Rajan, R.S., 2007. Managing in the middle: characterizing Singapore’s exchange rate policy. Asian economic journal, 21, 321–342. Cavoli, T. and Rajan, R.S., 2008. Extent of exchange rate flexibility in India. India macroeconomics annual 2007, 125–140. Cavoli, T. and Rajan, R.S., 2009. Exchange rate regimes and macroeconomic management in Asia. Hong Kong University Press. Cavoli, T. and Rajan, R.S., 2010. How flexible have Asian exchange rate regimes become in the post-crisis era? mimeo. Frankel, J. and Wei, S.J., 1994. Yen bloc or dollar bloc? Exchange rate in the East Asian economies. In: T. Ito and A. Krueger, eds. Macroeconomic linkage: savings, exchange rates, and capital flows. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Frankel, J. and Wei, S.J., 2007. Estimation of de facto exchange rate regimes: synthesis of the techniques for inferring flexibility and basket weights. IMF Annual Research Conference, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC, November 16. Ghosh, A., Gulde, A., Ostry, J., and Wolf, H., 1995. Does the nominal exchange rate regime matter? Working Paper No.95/121. IMF. Glick, R., Hutchison, M., and Moreno, R., 1999. Is pegging the exchange rate a cure for inflation? In: T.D. Willett, ed. Exchange-rate policies for emerging market economies. Boulder: Westview Press. Hansen, P., 1982. Large sample properties of generalized method of moments estimators. Econometrica, 50, 1029–1054. IMF (International Monetary Fund), 1997. World economic outlook. IMF. Levy-Yeyati, E.L. and Struzenegger, F., 2007. Fear of floating in reverse: exchange rate policy in the 2000s. mimeo. Ouyang, A.Y. and Rajan, R.S., 2009. Reserve accumulation and monetary sterilization in Singapore and Taiwan. Applied economics, forthcoming. Pontines, V. and Rajan, R.S., 2010. Foreign exchange market intervention and reserve accumulation in emerging Asia: is there evidence of “fear of appreciation? mimeo (January). Rajan, R.S., 2009. Asia and the global financial crisis. ISAS Insights No.76, Institute of South Asian Studies, National University of Singapore, July. Srinivasan, N., Mahambare, V., and Ramachandran, M., 2008. Preference asymmetry and international reserve accretion in India. Applied economics letters, 1–14. Subramanian, A., 2010. Who pays for the weak renminbi? Vox-EU, 11 February 2010. Surico, P., 2008. Measuring the time inconsistency of US monetary policy. Economica, 75, 22–38.

© Copyright 2025