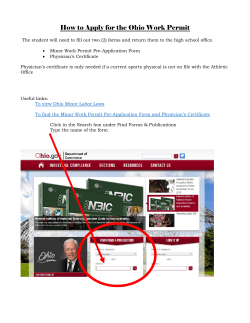

C S O