Child Abuse & Neglect

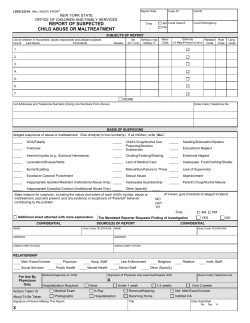

Child Abuse & Neglect 37 (2013) 14–21 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Child Abuse & Neglect Child physical and sexual abuse in a community sample of young adults: Results from the Ontario Child Health Study夽,夽夽 Harriet L. MacMillan a,b,∗ , Masako Tanaka a , Eric Duku a , Tracy Vaillancourt a,c , Michael H. Boyle a a Department of Psychiatry and Behavioural Neurosciences, McMaster University, 1280 Main Street West, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada L8S 4K1 Department of Pediatrics, McMaster University, 1280 Main Street West, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada L8S 4K1 Faculty of Education and School of Psychology, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Ottawa, Lamoureux Hall (LMX) 145, Jean-Jacques-Lussier Private, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada K1N 6N5 b c a r t i c l e i n f o Article history: Received 5 May 2012 Received in revised form 16 June 2012 Accepted 21 June 2012 Available online 3 January 2013 Keywords: Child physical abuse Child sexual abuse Prevalence Risk a b s t r a c t Objectives: Exposure to child maltreatment is associated with physical, emotional, and social impairment, yet in Canada there is a paucity of community-based information about the extent of this problem and its determinants. We examined the prevalence of child physical and sexual abuse and the associations of child abuse with early contextual, family, and individual factors using a community-based sample in Ontario. Methods: The Ontario Child Health Study is a province-wide health survey of children aged 4 through 16 years. Conducted in 1983, a second wave was undertaken in 1987 and a third in 2000–2001. The third wave (N = 1,928) included questions about exposure to physical and sexual abuse in childhood. Results: Males reported significantly more child physical abuse (33.7%), but not severe physical abuse (21.5%), than females (28.2% and 18.3%, respectively). Females reported significantly more child sexual abuse (22.1%) than males (8.3%). Growing up in an urban area, young maternal age at the time of the first child’s birth, and living in poverty, predicted child physical abuse (and the severe category), and sexual abuse. Childhood psychiatric disorder was associated with child physical abuse (and the severe category), while parental adversity was associated with child sexual abuse and severe physical abuse. Siblings of those who experienced either physical abuse or sexual abuse in childhood were at increased risk for the same abuse exposure; the risk was highest for physical abuse. Conclusions: These findings highlight important similarities and differences in risk factors for physical and sexual abuse in childhood. Such information is useful in considering approaches to prevention and early detection of child maltreatment. Clinicians who identify physical abuse or sexual abuse in children should be alert to the need to assess whether siblings have experienced similar exposures. This has important implications for assessment of other children in the home at the time of identification with the overall goal of reducing further occurrence of abuse. © 2012 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. 夽 This work was carried out at the Offord Centre for Child Studies, McMaster University. 夽夽 This study was funded by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). The research was also supported by the CIHR Institutes of Gender and Health; Aging; Human Development, Child and Youth Health; Neurosciences, Mental Health and Addiction; and Population and Public Health. Harriet MacMillan is supported by the David R. (Dan) Offord Chair in Child Studies. Michael Boyle is supported by a Canada Research Chair in the Social Determinants of Child Health. ∗ Corresponding author at: Offord Centre for Child Studies, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioural Neurosciences, McMaster University, 1280 Main Street West, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada L8S 4K1. 0145-2134/$ – see front matter © 2012 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.06.005 H.L. MacMillan et al. / Child Abuse & Neglect 37 (2013) 14–21 15 Introduction Despite increasing recognition that child maltreatment is a major public health problem, there continues to be relatively little community-based information available about the distribution and determinants of child abuse in Canada. The Canadian Incidence Study (CIS) provides important data about official reports of maltreatment (PHAC, 2010; Trocmé et al., 2005), but only a small proportion of child abuse victims come to the attention of child protection agencies (MacMillan, Jamieson, & Walsh, 2003). The Ontario Health Supplement, a 1990–1991 province-wide survey, examined the prevalence and correlates of mental health in a probability sample of residents 15 years of age and older and included questions about exposure to child physical and sexual abuse (Boyle et al., 1996; MacMillan et al., 1997; Offord et al., 1996). Although this information served to quantify the extent of the problem, it was collected retrospectively from a predominantly adult population at a single point in time. Furthermore, the Supplement was conducted more than 20 years ago. It is important to examine more recent information about the prevalence of maltreatment, and predictors of its occurrence from longitudinal studies. Based on the ecological approach, risk factors for abuse can be divided into four categories: demographic, familial, parental, and child (Belsky & Vondra, 1989). Of the longitudinal studies examining these factors, three involve general population samples. In two, exposure to child maltreatment was measured through retrospective self-reports and official agency reports, and in one study it was measured by retrospective self-report. The first study involved 644 families who were part of a larger sample of families randomly selected in 1975 from two upstate New York counties who were re-interviewed in 1983, 1986, and 1991–1993. Brown, Cohen, Johnson, and Salzinger (1998) identified variables linked to physical abuse, including low religious attendance, poor marital quality, single parent status, welfare, low parental involvement and other maternal factors such as serious illness, low education, youth and perinatal complications. The factors associated with child sexual abuse included being female, presence of disability in a child, harsh punishment, negative life events experienced by a child, parental death, presence of a stepfather, maternal youth, maternal sociopathy, and unwanted pregnancy. The second study, the Christchurch Health and Development Study, involved a birth cohort of 1,265 children in the Christchurch, New Zealand region recruited during mid-1977 and followed at four months and then annually until age 16 and then at 18 years followed by further assessments in adulthood. The following risk factors for child sexual abuse were identified: being female, marital conflict, low parental attachment, a high level of overprotection, and parental alcohol problems (Fergusson, Lynskey, & Horwood, 1996). The third study, the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health) followed by a US national sample of 20,745 adolescents (grades 7 through 12) into young adulthood (ages 18–26 years). Hussey, Chang, and Kotch (2006) identified the associations between lower parental education and physical neglect and physical assault, and the associations between lower family income and neglect and contact sexual abuse. In this study, child maltreatment experienced by the start of the 6th grade was measured. In general, risk factors for physical abuse include those associated with psychosocial disadvantage while risk factors for sexual abuse in childhood included family dysfunction, parental absence, and/or economic disadvantage. The Ontario Child Health Study (OCHS), a province-wide longitudinal study, included self-report questions regarding childhood abuse in the third wave when the original participants were young adults (Boyle et al., 1987; Boyle, Georgiades, Racine, & Mustard, 2007). The OCHS provides data about exposure to child abuse within a time frame closer to its occurrence than the earlier Ontario Health Supplement for most participants (more than 70% of Supplement respondents were over age 35 at the time of the survey), and prospective information on correlates. Additionally, the OCHS offers the opportunity to study childhood abuse within families. This study summarizes results from the OCHS regarding the prevalence of and risk factors for physical and sexual abuse in childhood. Methods The OCHS was conducted in 1983 to investigate the distribution and determinants of health status in children aged 4–16 years (Offord et al., 1987); a second wave in 1987 assessed continuity and change in health status (Offord et al., 1992); and a third wave in 2000–2001 investigated functional outcomes in young adulthood. Information was collected about children who were 4–16 years of age in 1983 for the first wave, and about the same children when they were four years older in 1987 for the second wave. By the time of the third wave, the children from the original sample were adults between the ages of 21–35 years. The target population in 1983 included all children born from January 1966 through January 1979 who resided in a household dwelling in the province of Ontario. The sampling frame was the 1981 Census; selection was made by stratified, clustered and random sampling. In 1983 and 1987, the “person most knowledgeable” (usually the mother) reported on the child. In 2000–2001, the children, now young adults, were respondents, and attempts were made to include all children who participated in 1983. Tracing, enlistment and data collection were completed by Statistics Canada. Participants gave verbal consent prior to the interview, and written consent to share the data with researchers at McMaster University. The study was approved by the Hamilton Health Sciences/McMaster University Research Ethics Board. Participants In the 1983 OCHS, there were 2,052 households with eligible children; 1,869 (91.1%) of these households including 3,294 children participated in the original study. Of these 3,294 children, 2,355 (71.5%) provided some information to the study 16 H.L. MacMillan et al. / Child Abuse & Neglect 37 (2013) 14–21 Items Minimum required frequency for: Physical abuse 1. How many times before age 16 did an adult slap you Severe physical abuse 3-5 times >10 times 3-5 times >10 times 1-2 times 1-2 times on the face, head or ears or hit or spank you with something like a belt, wooden spoon or something hard? 2. Before age 16 did an adult push, grab, shove or throw something at you to hurt you? 3. Before age 16 how many times did an adult kick, bite, punch, choke, burn you, or physically attack you in some way? Sexual abuse 1.Before age 16 when you were growing up, did anyone 1-2 times ever do any of the following things when you didn't want them to: touch the private parts of your body or make you touch their private parts, threaten or try to have sex with you or sexually force themselves on you? Note. Endorsing one or more items at or above the minimum required frequency was deemed abuse. Fig. 1. Definition of physical and severe physical abuse, and sexual abuse for the short form of the Childhood Experiences of Violence Questionnaire. in 2000–2001, while a sub-group of 1,928 (58.5%) were full participants. Fourteen key variables from 1983 were used to model the effects of attrition in both groups: these variables represented child health status, health service use and child functioning, parental health, and family structure, functioning and disadvantage. Several of these variables were significantly related to attrition; with the two strongest being rental housing and the child’s mental health/social service use. Attrition weights were developed separately for each group. When these attrition weights were applied to each group (N = 2,355 and N = 1,928), the original 1983 sample characteristics (N = 3,294) were re-captured accurately (Boyle et al., 2006, 2007). Measures Childhood physical and sexual abuse. Exposure to childhood physical abuse and sexual abuse before the age of 16 years was measured retrospectively in 2000-2001 with a modified version (Tanaka et al., 2012) of the Childhood Experiences of Violence Questionnaire (CEVQ; Walsh, MacMillan, Trocmé, Jamieson, & Boyle, 2008). In a sample of 179 adolescents aged 12–18 years from clinical and community settings, the original CEVQ showed good two-week test–retest reliability, with kappas of 0.85, 0.77, 0.92 and 0.87 for physical abuse, severe physical abuse, sexual abuse, and severe sexual abuse, respectively, and good criterion validity when measured against clinical assessment, with kappas of 0.67 and 0.70 for physical and sexual abuse, respectively. The CEVQ has demonstrated content and construct validity (Walsh et al., 2008). To reduce respondent burden, the CEVQ was shortened for the OCHS by the authors (HM, MB), mainly by combining items from the original; for example, the two items “kicked, bit, or punched you to hurt you?” and “choked, burned or physically attacked you in some other way?” became one: “kick, bite, punch, choke, burn you, or physically attack you in some way?”. Similarly, the one sexual abuse item is three items in the original CEVQ. As in the original, the response categories were “never”, “1 or 2 times”, “3 to 5 times”, “6 to 10 times” and “more than 10 times”. Fig. 1 shows the items in the short version and the frequency thresholds for severe and non-severe physical abuse and sexual abuse (with no severity classification based on one item that includes several abusive acts varying in severity). The shorter form of the CEVQ is comparable to the original CEVQ in the two-week test–retest reliability, criterion validity, and construct validity (Tanaka et al., 2012). The CEVQ was self-completed; most of the survey was administered face-to-face. H.L. MacMillan et al. / Child Abuse & Neglect 37 (2013) 14–21 17 Sociodemographic status. The socioeconomic status (SES) of each child’s family was determined from 1983 data, based on a composite measure derived from five variables which were standardized, added together and transformed to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one. These variables were the natural log of household income, years of education of the mother and her spouse/partner (if present in the home), and the prestige associated with the occupation of the mother and her spouse/partner (if present in the home and working) measured by the Blishen scale (Blishen, Carroll, & Moore, 1987). A variable classifying family income below Statistics Canada low income cut-offs (taking into account family size and area of residence) was included to represent extreme economic disadvantage. Urban/rural residence was also taken from 1983 data; urban was defined as a census area with a population over 25,000. Family characteristics. Other 1983 variables examined included parental and family characteristics: young mother status (20 years or younger) at time of first child’s birth; parental adversity which included being hospitalized for nerves and/or ever being arrested; family dysfunction, measured by maternal report on a twelve-item general dysfunction subscale of the McMaster Family Assessment Device (FAD; Byles, Byrne, Boyle, & Offord, 1988; Epstein, Baldwin, & Bishop, 1983). The scale includes 12 statements that describe family behavior and relationships in each of the dimensions, with response options that include the following: strongly agree (=1), agree (=2), disagree (=3), strongly disagree (=4). After recoding negativelyoriented items, a total score was obtained, which could range from 12 to 48, with lower scores indicating better functioning. For this analysis, responses were dichotomized as follows: at risk for family dysfunction (score of 27 and above) and not at risk (value below 27). Child characteristics. Child characteristics included presence of psychiatric disorder (defined as one or more of conduct disorder, emotional disorder and attention deficit disorder), based on the OCHS scales parent report (Boyle et al., 1987, 1993) and functional limitation as indicated by the child’s mother. A functional limitation was defined as a condition lasting six months or more and consisting of one or more restrictions in physical activity, mobility or self care due to an illness, injury or medical condition and/or a limitation in role performance (kind or amount of ordinary play or schoolwork) due to physical, emotional or learning problems. Analyses Because of the relatively high overlap of exposure to different types of abuse and small sample sizes associated with ‘pure’ categories, studies of child maltreatment rarely subdivide abuse into mutually exclusive types. Accordingly, respondents who reported both physical and sexual abuse in this study were included in both categories. OCHS data were weighted to compensate for differential sample loss (Boyle et al., 2007). Respondents with missing covariates were assigned mean (quantitative variables) or modal (qualitative variables) values, were classified as missing some information, and retained in the analysis. Prevalence estimates and between-sibling associations for child abuse came from weighted data using SPSS version 11.0.1. To estimate between-sibling associations for different types of abuse, we created a separate file of households that had information on the experience of child abuse from two or more siblings. Households with three or more siblings were subdivided so that the information collected on all combinations of two siblings could be analyzed. The resulting 2 × 2 tables were used to estimate conditional risk (i.e., chance of one sibling being exposed to abuse conditional on another sibling being exposed to the same type of abuse) as well as the relative odds and agreement on exposure to the same type of abuse within families. Sample weights were rescaled to sum to the total number of households to avoid generating unrealistically precise confidence intervals. To test the accuracy of these estimates, we modeled the strength of association between siblings in the occurrence of abuse using logistic regression, controlling for the number of paired comparisons in families with 3 or more siblings. The estimated odds ratios were almost identical to the estimates obtained in the simple analyses described above. Multilevel logistic regressions using weighted data with MLwiN (Rasbash et al., 2000) tested models for three outcomes: child physical abuse, sexual abuse, and severe physical abuse (see Fig. 1 for definitions). This study uses a two-level logistic regression with simultaneous consideration of i children, nested in j families. In models with two or more levels, each level is associated with its own, unexplained residual error. Residual error at the individual level is constrained to 1; each successive level is associated with its own error term e −N (0, ˚2 ) where ˚2 estimates the residual between-group variation (Snijders & Bosker, 1999). Final models are presented in which all of the covariates under consideration are included. Results Twenty-one (1.1%) respondents out of 1,928 did not have sufficient data to make a determination of child physical abuse; a further 14 (0.7%) did not answer the child sexual abuse item; 69 respondents were missing covariate data and were retained in the analysis. The final unweighted analysis sample was 1,893 (98.2% of 1,928). These 1,893 respondents came from 1,253 families; 757 individuals (40.0%) were the sole respondent in their family and 748 respondents (39.5%) were from two-respondent families. The remaining respondents were from three, four and five-respondent families. Respondent characteristics are described in Table 1. Of particular note, more than one-fifth of respondents (21.4%) were living in poverty as a child in 1983. Table 2 shows the prevalence of child abuse by sex for the OCHS sample. More males 18 H.L. MacMillan et al. / Child Abuse & Neglect 37 (2013) 14–21 Table 1 Characteristics of OCHS respondents by sex. Characteristic Males % (SE) N = 924a Married/cohabiting Childhood urban residence Living in poverty in childhood Maternal young age at first birth Family dysfunction Parental adversity Childhood psychiatric disorder Childhood functional limitation 49.1 (.02) 67.7 (.01) 21.9 (.01) 9.2 (.01) 11.1 (.01) 8.4 (.01) 14.4 (.01) 5.0 (.01) Characteristic Total % (SE) N = 1893a 58.6 (.02) 67.6 (.01) 21.0 (.01) 11.2 (.01) 10.6 (.10) 10.0 (.01) 8.2 (.01) 3.9 (.01) 53.7 (.01) 67.7 (.01) 21.4 (.01) 10.2 (.01) 10.8 (.01) 9.1 (.01) 11.4 (.01) 4.4 (.00) Females Mean (SE) Males Mean (SE) Childhood SES Age a Females % (SE) N = 969a 0.0 (1.00) 27.1 (.12) Total Mean (SE) 0.0 (1.00) 27.1 (.12) 0.0 (1.00) 27.1 (.09) Unweighted N; estimates based on weighted data. Table 2 Prevalence of self-reported childhood abuse by sex. Physical abuse Sexual abuse Severe physical abuse Physical and/or sexual abuse Both physical and sexual abuse a Total N = 1,893a % (SE) Males N = 924a % (SE) Females N = 969a % (SE) Rao-Scott 2 statistic p-value 31.0 (.01) 15.0 (.01) 19.9 (.01) 37.9 (.01) 8.1 (.01) 33.7 (.01) 8.3 (.01) 21.5 (.01) 37.1 (.01) 4.9 (.01) 28.2 (.01) 22.1 (.01) 18.3 (.01) 38.8 (.02) 11.6 (.01) 4.81 50.68 2.16 0.46 19.18 .03 <.0001 .14 .50 <.0001 Unweighted N; estimates based on weighted data. Table 3 Physical and sexual abuse occurring within families. Physical abuse Percentage of sibling pairs where both reported same type of abuse among families where at least one respondent reported abusea Risk: OR (95% CI) Agreement: Kappa (SE) Severe physical abuse Sexual abuse 50.0, 54.6 32.3, 32.6 23.4, 24.3 3.8 (2.5–5.7) .30 (.05) 2.5 (1.5–4.1) .16 (.05) 2.0 (1.1–3.6) .10 (.05) Number (unweighted) of 2+ respondent families N = 496. Number (unweighted) of within family pairs N = 809 (from 374 in 2 respondent households; 103 in 3 respondent households; 16 in 4 respondent households; 3 in 5 respondent households). a Two percentages for each abuse type represent conditional risk related to each sibling in the pair. than females reported exposure to physical abuse in childhood, while child sexual abuse was substantially higher among females than males. Within multiple-child households, there was increased risk of another child being exposed to physical abuse (odds ratio (OR) = 3.8, 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.5–5.7) as well as severe physical abuse (OR = 2.5, 95% CI = 1.5–4.1) and sexual abuse (OR = 2.0, 95% CI = 1.1–3.6) if one child reported such experiences; the risk was highest for physical abuse (Table 3). Also shown in Table 3 are the percentages of sibling pairs where both respondents reported exposure to the same type of abuse among families in which at least one reported abuse as well as the level of agreement based on Cohen’s Kappa. Table 4 shows the results of multilevel logistic regressions for the three abuse outcomes. Child physical abuse and severe physical abuse were both associated with living in poverty, urban residence, child psychiatric disorder and young maternal age at the time of the first child’s birth. Age (older) and sex (male) were significant predictors of child physical abuse only and not the severe category. Of particular note, parental adversity was a significant predictor of severe child physical abuse. The significant predictors for child sexual abuse included being female, presence of parental adversity, age (older), urban residence, living in poverty and young maternal age at the time of the first child’s birth. Discussion The OCHS provides population-based information about the prevalence of exposure to child physical and sexual abuse. Although the measures and timing of retrospective reports are somewhat different, some comparison is warranted with the H.L. MacMillan et al. / Child Abuse & Neglect 37 (2013) 14–21 19 Table 4 Models of physical and sexual abuse: estimated odds ratios (ORs) and confidence intervals. Variable Demographic Male Age Childhood urban residence Childhood SES Living in poverty in childhood Parent/family Young maternal age at first birth Parent adversity (hospitalized for nerves/arrested) Family dysfunction Child Psychiatric disorder Functional limitation Missing data Random effects Level 2 (family) (SE) Level 1 (individual) * Physical abuse OR (95% CI) Severe physical abuse OR (95% CI) Sexual abuse OR (95% CI) 1.3 (1.0–1.5)* 1.0 (1.0–1.1)* 1.3 (1.0–1.6)* 1.0 (0.8–1.1) 1.4 (1.1–2.0)* 1.1 (0.9–1.4) 1.0 (1.0–1.0) 1.3 (1.0–1.7)* 1.0 (0.8–1.1) 1.6 (1.1–2.3)* 0.3 (0.2–0.4)* 1.1 (1.0–1.1)* 1.6 (1.2–2.1)* 0.9 (0.8–1.1) 1.5 (1.0–2.1)* 1.6 (1.1–2.3)* 1.3 (0.9–1.9) 1.2 (0.8–1.7) 1.6 (1.1–2.3)* 1.6 (1.1–2.4)* 1.4 (1.0–2.1) 2.0 (1.3–2.8)* 2.2 (1.5–3.3)* 1.4 (0.9–2.2) 1.9 (1.4–2.6)* 1.5 (0.9–2.5) 1.1 (0.6–2.0) 1.7 (1.1–2.4)* 1.4 (0.8–2.5) 0.7 (0.3–1.4) 1.4 (0.9–2.1) 1.6 (0.9–2.9) 0.7 (0.3–1.7) 0.52 (0.12)* 1.00 0.51 (0.21)* 1.00 0.16 (0.26) 1.00 p < .05. earlier Ontario community data from the Ontario Health Supplement discussed in the Introduction. In the Supplement, the Child Maltreatment History Self-Report (CMHSR) assessed physical abuse (6 items) and sexual abuse (4 items) by an adult while the respondent was “growing up”; the OCHS CEVQ physical abuse item stems are similar “before age 16, did an adult. . .”. Comparing the sample aged 21–35 from the Supplement, rates of physical abuse are similar: 30.0% of Supplement males and 22.9% Supplement females report child physical abuse. However, the OCHS shows higher rates of child sexual abuse for males and females: 22.1% of OCHS females compared with 14.1% in the Supplement females; 8.3% of OCHS males compared with 3.3% of Supplement males. Both questionnaires ask about events occurring to the respondent during childhood; however, the OCHS CEVQ sexual abuse stem inquires about “anyone” whereas the CMHSR specified “an adult”. This could account for the higher rates of child sexual abuse in the OCHS sample as it is now recognized that the perpetrators of sexual abuse in childhood are often younger than 18 (Finkelhor, 1994; Finkelhor, Ormrod, Turner, & Hamby, 2005). The OCHS findings with regard to sex differences are consistent with the Supplement findings (MacMillan et al., 1997). The OCHS has some important advantages over the Supplement; information on risk factors for abuse was gathered prospectively from informants other than the respondents. The study by Brown et al. (1998) and the Christchurch Health and Development Study (Fergusson et al., 1996) have the advantage of access to official child protection agency reports available for comparison with self-reports; this was not possible for the OCHS because of concerns about confidentiality. The child maltreatment questions asked in the study by Brown and colleagues were quite limited with one question for each of physical abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect. In the case of the Christchurch Health and Development Study, respondents were asked about a series of 15 sexual acts. In the study by Hussey et al. (2006), maltreatment measures were modified versions of previous studies with one question for each of supervision neglect, physical neglect, physical assault, and contact sexual abuse. The OCHS has the advantage of using a child maltreatment measure that has been evaluated for its reliability and validity. Despite such wide variability in the measures used to ask retrospectively about exposure to maltreatment, it is useful to compare the risk factors identified by the OCHS with the US and New Zealand-based studies. It is difficult to interpret the finding of increased risk for exposure to physical (and severe physical) and sexual abuse for those who resided during childhood in communities with populations of over 25,000 residents. In the Supplement, child physical abuse was reported more commonly among females raised in rural areas compared to those who grew up in urban areas; no such association was found for males (MacMillan et al., 1997). Rural for the Supplement was defined as a community with fewer than three thousand residents, so a direct comparison is not possible. To our knowledge, urban residence in childhood has not been identified previously as a risk indicator for maltreatment. Of particular note is the OCHS finding that a general measure of SES was not a significant predictor of either child physical or severe physical abuse, but living in poverty in childhood – a measure of extreme disadvantage – was associated with an increased risk of physical (and severe physical) and sexual abuse. The association between living in poverty and child sexual abuse differs from some reports in the literature (Finkelhor et al., 2005; Finkelhor, 1994; MacMillan et al., 1997). Although official reports of victimization have shown an association between low SES and child sexual abuse, this has been considered a reporting bias, whereby suspicions of maltreatment in low-income families are more likely to be reported (Hampton & Newberger, 1985). In the study by Brown et al. (1998), child physical abuse but not sexual abuse was predicted by welfare dependence. Similarly in the Christchurch Health and Development Study, there were no significant associations between child sexual abuse and family socioeconomic status, although lower levels of maternal education were associated with increasing rates of child sexual abuse. Although Hussey et al. (2006) found a significant association between family income 20 H.L. MacMillan et al. / Child Abuse & Neglect 37 (2013) 14–21 below the federal poverty level and child sexual abuse, their measurement of child abuse (by 6th grade) does not capture child sexual abuse that occurred during adolescence. One of the most important findings in the OCHS is the consistency with which the first child being born to a young mother predicted child physical abuse (and the severe category), and sexual abuse. This risk factor was associated with abuse after controlling for family SES and poverty. Maternal youth was associated with both child physical and sexual abuse in the New York study, but does not appear to have been measured in the Christchurch Health and Development Study and Add Health. Parental adversity was a predictor of child sexual abuse in the OCHS; this was also the case for both the New York (maternal sociopathy) and New Zealand-based studies, especially parental alcoholism in the latter. Finkelhor et al. (2005) have suggested that the unavailability of a parental figure may place a child at risk for exposure to child sexual abuse. These studies support this hypothesis. The findings about risk of exposure to abuse among siblings are particularly notable: this information highlights the importance of considering risk to other siblings in a household where one child is identified as a victim of physical abuse (including the severe category), as well as sexual abuse. Given that parents are most commonly the perpetrators of child physical abuse, but this is not the case for child sexual abuse (Gilbert et al., 2009), it is not surprising that the risk for the same exposure among siblings is higher for physical than sexual abuse. However, a two-fold risk of sexual abuse in siblings is important; in this sample, among sibling pairs where one respondent reported exposure to sexual abuse in childhood, in almost 25% of those pairs, both siblings reported such exposure, emphasizing the need to consider the risk to siblings in clinical evaluations. Strengths and limitations The validity of the findings of the present study is strengthened by the fact that information about predictors was collected in 1983 and from informants other than those providing information about exposure to maltreatment. It is possible to identify young maternal age at time of first birth as a risk factor, since it clearly preceded the child’s exposure to maltreatment, and the potential confounding effects of low socioeconomic status at the point of assessment in 1983 are taken into account. Other predictors can, at most, be described as risk indicators, since it is unknown whether the other significant parent/family variables preceded or followed abuse. This is particularly the case for child variables such as presence of child psychiatric disorder, which was associated with child physical and severe physical abuse, but not exposure to sexual abuse. Some authors criticize the retrospective approach to asking about exposure to child maltreatment (Widom, Raphael, & Dumont, 2004). But as others emphasize, to measure this contemporaneously requires identification of maltreated children in the community with all the legal and ethical challenges inherent in doing so (Kendall-Tackett & Becker-Blease, 2004). Focusing exclusively on maltreated children involved with the child protection system is also not the answer: prospective designs with such samples would likely miss a large proportion of those abused. Data from the Supplement suggest that only 5% of those who reported either child physical or sexual abuse or both, reported contact with the child protection system (MacMillan et al., 2003). In a study by Kendall-Tackett (1991), 82% of those who disclosed sexual abuse indicated that they had never reported this to a child protection or legal agency. She suggests that participants in prospective and retrospective studies of child maltreatment may be two distinct sub-groups, and it is important to have information from both samples. The OCHS did not include questions about exposure to neglect because of the challenges in measuring its occurrence, especially retrospectively, in large community-based surveys. It is one of the most common and serious forms of child maltreatment (Trocmé et al., 2005), and developing reliable and accurate approaches to measure it should be a priority (Sullivan, 2000). As progress is made in defining neglect (Dubowitz et al., 2005), we hope it will be possible to incorporate psychometrically sound questions in future Canadian surveys. Much less research is available to inform approaches to measuring emotional abuse within the context of a community-based survey (Tonmyr, Draca, Crain, & MacMillan, 2011). Ideally a survey would include questions about all major categories: child physical, sexual, emotional abuse, neglect and exposure to intimate partner violence. The third wave of the OCHS was conducted when the respondents were young adults; it would be preferable for information about exposure to maltreatment to be first collected in adolescence. Such information collected from population-based samples of youths, combined with surveillance data about the incidence of reported child maltreatment using the CIS would provide the most comprehensive knowledge about child maltreatment, one of the major public health problems affecting Canadian children and youths. Conclusions The OCHS provides important information about the high prevalence of exposure to child physical and sexual abuse. Noteworthy is the strong evidence for the association between young maternal age at the time of first birth, living in poverty in childhood and urban residence, and both types of abuse. This is new information for health care providers and child protection workers, as previous studies have suggested that these factors were associated primarily with child physical abuse, but not sexual abuse. Our findings suggest that children with these characteristics should be considered at risk of experiencing both child physical and sexual abuse. Furthermore, identification of these factors lends additional support to the recommendation by Olds and Kitzman (1990) to target interventions to communities where there are high rates of teenage parenthood and poverty. Given the commonalities in risk indicators for both child physical and sexual abuse, H.L. MacMillan et al. / Child Abuse & Neglect 37 (2013) 14–21 21 it would be important to determine if implementation of effective programs such as the Nurse Family Partnership (Olds, Sadler, & Kitzman, 2007), which has been shown to reduce official reports of child maltreatment, results in reductions in specific subtypes of child maltreatment, such as physical and sexual abuse. Our results also emphasize the importance of child protection workers and health care providers assessing the siblings of children exposed to child physical and sexual abuse. The fact that the co-occurrence of sexual abuse and even more so physical abuse (as well as the severe category) in childhood is so high among siblings, gives strong rationale to implementing policies that ensure all children in a household where one child is identified as physically or sexually abused, are also assessed for such exposure. References Belsky, J., & Vondra, J. (1989). Lessons from child abuse: The determinants of parenting. In D. Cicchetti, & V. Carlson (Eds.), Current research and theoretical advances in child maltreatment (pp. 153–202). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. Blishen, B. R., Carroll, W. K., & Moore, C. (1987). The 1981 socioeconomic index for occupations in Canada. Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology, 24, 465–488. Boyle, M. H., Georgiades, K., Racine, Y., & Mustard, C. (2007). Neighborhood and family influences on educational attainment: Results from the Ontario Child Health Study follow-up 2001. Child Development, 78, 168–189. Boyle, M. H., Hong, S., Georgiades, K., Duku, E., Racine, Y., & Mustard, C. (2006). Ontario Child Health Study Follow-up 2001: Evaluation of sample loss. Hamilton, Ontario: Offord Centre for Child Studies. Boyle, M. H., Offord, D. R., Campbell, D., Catlin, G., Goering, P., Lin, E., & Racine, Y. A. (1996). Mental health supplement to the Ontario Health Survey: Methodology. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 41, 549–558. Boyle, M. H., Offord, D. R., Hofmann, H. G., Catlin, G. P., Byles, J. A., Cadman, D. T., Crawford, J. W., Links, P. S., Rae-Grant, N. I., & Szatmari, P. (1987). Ontario Child Health Study. I. Methodology. Archives of General Psychiatry, 44, 826–831. Boyle, M. H., Offord, D. R., Racine, Y., Sanford, M., Szatmari, P., & Fleming, J. E. (1993). Evaluation of the original Ontario Child Health Study scales. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 38, 397–405. Brown, J., Cohen, P., Johnson, J. G., & Salzinger, S. (1998). A longitudinal analysis of risk factors for child maltreatment: Findings of a 17-year prospective study of officially recorded and self-reported child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse & Neglect, 22, 1065–1078. Byles, J., Byrne, C., Boyle, M. H., & Offord, D. R. (1988). Ontario Child Health Study: Reliability and validity of the general functioning subscale of the McMaster Family Assessment Device. Family Process, 27, 97–104. Dubowitz, H., Newton, R. R., Litrownik, A. J., Lewis, T., Briggs, E. C., Thompson, R., English, D., Lee, L. C., & Feerick, M. M. (2005). Examination of a conceptual model of child neglect. Child Maltreatment, 10, 173–189. Epstein, N. B., Baldwin, L. M., & Bishop, D. S. (1983). The McMaster Family Assessment Device. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 9, 171–180. Fergusson, D. M., Lynskey, M. T., & Horwood, L. J. (1996). Childhood sexual abuse and psychiatric disorder in young adulthood: I. Prevalence of sexual abuse and factors associated with sexual abuse. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 35, 1355–1364. Finkelhor, D. (1994). Current information on the scope and nature of child sexual abuse. The Future of Children, 4, 31–53. Finkelhor, D., Ormrod, R., Turner, H., & Hamby, S. L. (2005). The victimization of children and youth: A comprehensive, national survey. Child Maltreatment, 10, 5–25. Gilbert, R., Widom, C. S., Brown, K., Fergusson, D., Webb, E., & Janson, S. (2009). Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet, 373, 68–81. Hampton, R. L., & Newberger, E. H. (1985). Child abuse incidence and reporting by hospitals: Significance of severity, class, and race. American Journal of Public Health, 75, 56–60. Hussey, J. M., Chang, J. J., & Kotch, J. B. (2006). Child maltreatment in the United States: Prevalence, risk factors, and adolescent health consequences. Pediatrics, 118, 933–942. Kendall-Tackett, K. A. (1991). Characteristics of abuse that influence when adults molested as children seek treatment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 6, 486–493. Kendall-Tackett, K., & Becker-Blease, K. (2004). The importance of retrospective findings in child maltreatment research. Child Abuse & Neglect, 28, 723–727. MacMillan, H. L., Fleming, J. E., Trocmé, N., Boyle, M. H., Wong, M., Racine, Y. A., Beardslee, W. R., & Offord, D. R. (1997). Prevalence of child physical and sexual abuse in the community. Results from the Ontario Health Supplement. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 278, 131–135. MacMillan, H. L., Jamieson, E., & Walsh, C. A. (2003). Reported contact with child protection services among those reporting child physical and sexual abuse: Results from a community survey. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27, 1397–1408. Offord, D. R., Boyle, M. H., Racine, Y. A., Fleming, J. E., Cadman, D. T., Blum, H. M., Byrne, C., Links, P., Lipman, E. L., MacMillan, H. L., Sanford, M. N., Szatmari, P., Thomas, H., & Woodward, C. A. (1992). Outcome, prognosis and risk in a longitudinal follow-up study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 31, 916–923. Offord, D. R., Boyle, M. H., Campbell, D., Goering, P., Lin, E., Wong, M., & Racine, Y. A. (1996). One-year prevalence of psychiatric disorder in Ontarians 15 to 64 years of age. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 41, 559–563. Offord, D. R., Boyle, M. H., Szatmari, P., Rae-Grant, N. I., Links, P. S., Cadman, D. T., Byles, J. A., Crawford, J. W., Blum, H. M., Byrne, C., Thomas, H., & Woodward, C. A. (1987). Ontario Child Health Study. II. Six-month prevalence of disorder and rates of service utilization. Archives of General Psychiatry, 44, 832–836. Olds, D. L., & Kitzman, H. (1990). Can home visitation improve the health of women and children at environmental risk? Pediatrics, 86, 108–116. Olds, D. L., Sadler, L., & Kitzman, H. (2007). Programs for parents of infants and toddlers: Recent evidence from randomized trials. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48, 355–391. Public Health Agency of Canada. (2010). Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect – 2008: Major Findings. Ottawa. Rasbash, J., Browne, W. J., Goldstein, H., Yang, M., Plewis, I., Healy, M., Woodhouse, G., Draper, D., Langford, I., & Lewis, T. (2000). A user’s guide to MLwiN, Version 2.1d. London: Institute of Education, University of London. Snijders, T., & Bosker, R. (1999). Multilevel analysis: An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. London: SAGE Publications. Sullivan, S., & for the Family Violence Prevention Unit, Health Canada. (2000). Child Neglect: Current definitions and models—A review of child neglect research 1993–1998. Ottawa, Canada: The National Clearinghouse on Family Violence. Cat. H72-21/171-2000E. Tanaka, M., Wekerle, C., Leung, E., Waechter, R., Gonzalez, A., Jamieson, E., & MacMillan, H. L. (2012). Preliminary Evaluation of the Childhood Experiences of Violence Questionnaire Short Form. Brief Note. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27(2), 396–407. Tonmyr, L., Draca, J., Crain, J., & MacMillan, H. L. (2011). Measurement of emotional/psychological child maltreatment: A review. Child Abuse and Neglect, 35, 767–782. Trocmé, N., Fallon, B., MacLaurin, B., Daciuk, J., Felstiner, C., Black, T., Tonmyr, L., Blackstock, C., Barter, K., Turcotte, D., & Cloutier, R. (2005). Canadian incidence study of reported child abuse and neglect: Major findings – 2003. Ottawa, Canada: Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada. Walsh, C. A., MacMillan, H. L., Trocmé, N., Jamieson, E., & Boyle, M. H. (2008). Measurement of victimization in adolescence: Development and validation of the Childhood Experiences of Violence Questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32, 1037–1057. Widom, C. S., Raphael, K. G., & DuMont, K. A. (2004). The case for prospective longitudinal studies in child maltreatment research: Commentary on Dube, Williamson, Thompson, Felitti, and Anda (2004). Child Abuse & Neglect, 28, 715–722.

© Copyright 2025