Document 282872

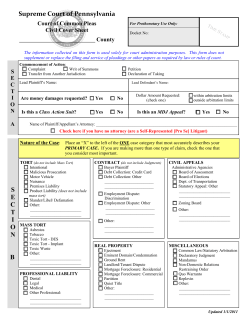

This is a sample of the instructor resources for The Law of Healthcare Administration, Fifth Edition by J. Stuart Showalter. This sample contains the instructor notes and PowerPoint slides for chapter 3. This complete instructor resources consist of 129 pages of instructor notes, 102 PowerPoint Slides, and access to a test bank. If you adopt this text you will be given access to the complete materials. To obtain access, e-mail your request to hap1@ache.org and include the following information in your message. • • • • • • Book title Your name and institution name Title of the course for which the book was adopted and season course is taught Course level (graduate, undergraduate, or continuing education) and expected enrollment The use of the text (primary, supplemental, or recommended reading) A contact name and phone number/e-mail address we can use to verify your employment as an instructor You will receive an e-mail containing access information after we have verified your instructor status. Thank you for your interest in this text and the accompanying instructor resources. CHAPTER 3 Negligence I. Overview I began an earlier iteration of these materials with a bit of an essay, which is reproduced here (for what it’s worth). Beneath the extraordinary complexity of modern U.S. law lies an equally extraordinary simplicity, “as clear and orderly as anatomy.”1 People have certain obligations toward each other; these obligations may be in the form of criminal laws, standards of ordinary prudence, or duties voluntarily assumed, but wherever they are found, their breach can be remedied through legal action rather than self-help and personal conflict. Nowhere else is this basic simplicity of the law more evident than in the field of negligence, the most common form of litigation and the field that probably owes more to our common-law roots than any other. Negligence is a branch of torts. A tort, simply put, is a kind of wrong. Crimes and breaches of contract are wrongs as well, of course, but negligence is a civil wrong that is neither criminal nor contractual and involves the violation of an instinctual rule of behavior— one of those basic obligations we owe each other—the obligation to be careful and prudent in our relationships. This concept seems self-evident, but until the late nineteenth century it was caught in a hopeless tangle of behavioral rules that had no “underlying principle to explain their diversity.”2 But in the summer of 1880, the giant of American jurisprudence, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., saw a simple principle that seemed to bring order into the jumble: The organizing principle of the law was not found in the rules themselves, which were hopelessly diverse, as disparate and varied as the circumstances of human behavior. People came into court because they had been injured in some way and not because someone had violated a rule of behavior. Was the injury being complained of an accident—of which the law took no notice—or was it someone’s fault? Under the skin of modern law lay not rules of behavior but a primitive impulse: blame. “Even a dog distinguishes between being stumbled over and being kicked.”3 The law of torts was simply the line drawn between accidental and blameworthy injuries. The line had not been drawn all at once, but by cautious decisions in one case after another. The concept of blame had evolved from an instinctive impulse for retribution to a modern notion of fairness. People were now held accountable only for injuries they might have foreseen and forestalled. What a person of ordinary intelligence and foresight could not foresee was accidental and therefore blameless. Holmes developed these insights, never before understood or explained, as much like a philosopher as a legal scholar. In a series of 12 masterful lectures he explained how the law Photocopying and distributing this PDF of the Instructor's Manual is prohibited without the permission of Health Administration Press, Chicago, Illinois. For permission, please fax your request to (312) 424-0014 or e-mail hap1@ache.org. 1 had developed through “the force of [society’s] collective instinct,”4 and he set the stage for the twentieth century’s emphasis on substantive fairness. The lectures were then published as a book entitled The Common Law, perhaps the most important single volume in American jurisprudence before or since. The Common Law begins with an oft-quoted paragraph that summarizes in a few eloquent words the reasons why so many respect and revere our legal system: The life of the law has not been logic; it has been experience. The felt necessities of the time, the prevalent moral and political theories, institutions of public policy, avowed or unconscious, even the prejudices which judges share with their fellow men, have had a good deal more to do than the syllogism in determining the rules by which men should be governed. The law embodies the story of a nation’s development through many centuries, and it cannot be dealt with as if it contained only the axioms and corollaries of a book of mathematics.5 Experience, the “life of the law,” teaches that negligence embodies four simple concepts: duty, breach, injury, and causation. These are the subjects of Chapter 3 and its accompanying case materials. II. Main Topics • The general principles of negligence • Proving the standard of care • Distinctions among causes of action • Tort-reform proposals • Alternatives to the tort system III. Questions, Answers, and Talking Points Page 54—Legal Brief. Students will be incredulous to learn that if the glaucoma test is 95 percent accurate and the incidence is 1 in 25,000, only about one of every six people who get a positive test result actually has the disease. You might ask students to do some research on other conditions and the relative accuracy of their tests. The public policy issues suggested in the last paragraph of the box would make for good classroom discussion or a research project. Photocopying and distributing this PDF of the Instructor's Manual is prohibited without the permission of Health Administration Press, Chicago, Illinois. For permission, please fax your request to (312) 424-0014 or e-mail hap1@ache.org. 2 Page 68—Legal DecisionPoint. This call-out box and the related text present a couple of classic “what if” scenarios for discussion. If you wish, you can get into a Cardozo-like discussion of causation; remember the famous Palsgraf case? In the Navy case mentioned in the textbook (page 68), the government was held liable, although the Department of Justice and the Navy (in the person of a certain young Judge Advocate General officer) vigorously objected. I still believe the case was wrongly decided, but “deep pockets” come into play when the U.S. Government is the defendant. The lab courier hypothetical could go either way depending on such facts as the length of the permitted lunch hour, whether these kinds of “detours” had been tolerated in the past, whether the driver was back on his regular route at the time of the accident, etc. Page 72—Legal Brief. The physician’s typical reaction to a favorable verdict is to seek revenge. “Now let’s sue the patient and the lawyers!” is the typical rallying cry. I even had one come to me wanting to sue the judge! (I had to give him a mini lesson in judicial immunity.) Learned Hand’s admonition is good to remember. Page 77—Figure 3.1. This was an interesting settlement and, I believe, the Navy’s first medical malpractice settlement involving a reversionary trust. Economists and actuaries helped me calculate what amount of corpus would be necessary to fund the patient’s treatment for a possible 70-plus-year life span. I carried the trust document and settlement agreement to the Department of Justice, personally got the signature of the Deputy Attorney General, and hand delivered the $1 million check to the trust company. This was in the fall of 1979, and I have often wondered what happened to Marianne H., who would now be a little over 30 years old. Page 77—Chapter Discussion Questions. The answers to the first five of these should be self-explanatory. As to question 6, I think the various tort-reform efforts have had strikingly mixed results. In my humble opinion, they are highly politicized “Band-Aid” approaches to a recurring problem. The fact is that we have a malpractice insurance “crisis” every couple of decades, and it just so happens to coincide with a downturn in the stock market. When the amount of investment income falls, insurance companies start Photocopying and distributing this PDF of the Instructor's Manual is prohibited without the permission of Health Administration Press, Chicago, Illinois. For permission, please fax your request to (312) 424-0014 or e-mail hap1@ache.org. 3 raising premiums and blaming the tort system. But the problem is not essentially the system or even plaintiffs’ attorneys (although each can share some of the blame); instead, the problem stems from bad medical outcomes, bad doctor–patient rapport, and a broken healthcare system that dehumanizes people. Page 84—Helling v. Carey Discussion Questions 1. Personally, I think Helling was much ado about very little. The physicians were in a snit because lawyers and judges were telling them what to do, but the facts were so unusual that they were unlikely to recur. The net effect, however, was to send the medical profession a wake-up call and make them think twice before blindly following the “we’ve always done it this way” approach. 2. Yes, it’s “judge-made law,” and there’s nothing wrong with that. It’s what judges do: they judge. 3. See the answer to question 1—Doctors have wised up, and the situation is no longer much of an issue. 4. See the discussion above. Page 88—Perin v. Hayne Discussion Questions 1. This question involves a nuance: due care does not need to be proven; the plaintiff must prove a lack of due care. The trial court found that the injury could occur even if proper techniques were used. 2. The injury wouldn’t happen without negligence. The usual res ipsa loquitur case involves circumstances that any layperson could tell resulted from negligence— barrels of flour don’t fall out of warehouses unless someone was negligent, for example. But in surgery, a layperson is not qualified to tell if negligence was involved. The court says it doesn’t matter; the principle still applies. 3. This is another philosophical question of where to draw the line. You can make up some interesting scenarios: switching body parts (left versus right ear, for example); using a second incision; removing the appendix while repairing a hernia because “we were in the neighborhood”; doing blepharoplasty on both the upper and lower eyelids when only one or the other was desired. Using an “objective patient” test is essential. Photocopying and distributing this PDF of the Instructor's Manual is prohibited without the permission of Health Administration Press, Chicago, Illinois. For permission, please fax your request to (312) 424-0014 or e-mail hap1@ache.org. 4 4. Probably because the plaintiff did not raise the issue. It might have been interesting, however, if she had come into court saying, “If I had only known, I would not have consented.” IV. PowerPoint Slides and Lecture Notes These slides and notes are presented here for your use in preparing for your classroom sessions. You may download the full slide presentation at www.ache.org/pubs/classroom/showalter/show5power.ppt • General Principles of Negligence • What is a “tort”? • A civil wrong not based on contract • • – Usually based on “fault” – Strict liability uncommon in healthcare – Intentional torts in Chapter 2 See the taxonomy in the first slide for Chapter 2 IM. A tort is a civil wrong that is not based on contract. To prove liability, the plaintiff must prove each of the four elements: duty, breach, injury, and causation. • Elements – – – – Duty Breach Injury Causation • Elements of Negligent Tort • Duty – How to establish? – Published standard of care – “Due care in the circumstances” • foreseeability • reasonable person • Breach of duty • Injury • Causation • The duty is often proven by showing a “standard of care” through written evidence (a Joint Commission standard or hospital policy, for example) or expert testimony. If a published standard of care or expert testimony cannot be obtained, “due care under the circumstances” will be used as the standard. Photocopying and distributing this PDF of the Instructor's Manual is prohibited without the permission of Health Administration Press, Chicago, Illinois. For permission, please fax your request to (312) 424-0014 or e-mail hap1@ache.org. 5 • Misc. Thoughts • “Locality rule” • “Respected minority” rule • Respondeat superior vs. independent contractor • Tort reform • • • The “locality rule”—which required expert witnesses to be from or at least familiar with the practice of medicine in the locality where the defendant practices—has pretty much been discredited. We are generally considered to have a national standard of care. A “structured settlement” $1 million Annual cost Reversionary trust $$ 0 • • Age 72 Example of a periodic payment settlement. The graph is an example of a case I had in the Navy. On my The “respected minority rule” recognizes that there may be multiple standards because medicine is practiced differently by people with different schools of thought. The defense that a member of a hospital’s medical staff is an “independent contractor” whose negligence cannot render the hospital liable has been weakened in recent years. Various types of tort reform have been considered in recent years due to malpractice insurance crises. These proposals are discussed in the text. —Caps on noneconomic damages (pain and suffering) —Arbitration —Periodic payments —Shorter statute of limitations recommendation, the government set up a reversionary trust for the benefit of an infant with profound cerebral palsy and a life expectancy of 72 years. We did an analysis of the costs of caring for this person 24/7 for her entire life, reduced the cost to present value, then determined what amount of money would be needed to provide for her. With accumulated interest for the life of the child, we determined that $1 million of principal would be enough to fund the trust. Should the child die prematurely, the remaining principal and interest would revert to the government. Photocopying and distributing this PDF of the Instructor's Manual is prohibited without the permission of Health Administration Press, Chicago, Illinois. For permission, please fax your request to (312) 424-0014 or e-mail hap1@ache.org. 6 V. Additional Material The following opinion is provided for your use, if desired. You might want to make copies and assign it as additional reading. Discussion Questions and Suggested Answers are also provided at the end of the case. Marshall v. Yale Podiatry Group 5 Conn. App. 5, 496 A.2d 529 (1985) Dupont, C. J. This case presents the question of whether an orthopedic surgeon is qualified to testify as an expert as to the standard of care required in connection with the performance of foot surgery by a licensed podiatrist certified in the field of surgery. This is a medical malpractice action arising out of surgery performed by the defendant Jeffrey Yale, a licensed podiatrist in Connecticut, on the plaintiff’s right and left feet. Yale is an agent and employee of the defendant Yale Podiatry Group, P.C. His examination of the plaintiff disclosed a hallux limitus of the right foot (restricted, painful range of big toe motion) and a tailor’s bunion of the left foot. To alleviate the plaintiff’s condition, Yale operated on the plaintiff implanting an artificial joint in the plaintiff’s right, big toe and removing a portion of the plaintiff’s left small toe. At trial, the plaintiff called Urelich Weil, an orthopedic surgeon, to testify to the applicable standard of care for such surgery. The defendants objected to Weil’s testifying, claiming that he was not qualified to testify as to the applicable standard of care. The trial court sustained the defendants’ objection and the plaintiff excepted. Weil was the plaintiff’s only expert witness and therefore the plaintiff rested since without his testimony the plaintiff could not prevail. The defendants moved for a directed verdict, which the trial court granted. The plaintiff moved to set aside the verdict, which the trial court denied and the plaintiff appealed. The standard of care to which physicians and surgeons are held is “that which physicians and surgeons in the same general neighborhood and in the same general line of practice ordinarily have and exercise in like cases.” When the court formulated that test, the “same general neighborhood” was interpreted as a territorial limitation restricted to the confines of the community in which the doctor practiced. In [a 1932 case], the “general neighborhood” was considered the state of Connecticut. It has now been broadened to include the entire nation. These cases reveal a trend towards the liberalization of the rules involving the qualifications of medical experts. Although the issue of this case does not involve the geographical limitation on medical expert testimony, but rather the “general line of practice” limitation on expert medical testimony offered in a medical malpractice action, the liberalization of the evidentiary rules regarding the former limitation are relevant in analyzing the latter limitation. Our analysis of cases starts with [a 1975 decision] where the court found that the trial court erred in excluding the plaintiff’s expert, a practicing surgeon specializing in breast cancer surgery, from testifying as to the proper medical standards of practice among obstetriciangynecologists pertaining to breast examinations. In that case, the testimony was “that breast lump examinations are performed in exactly the same manner by obstetrician-gynecologists and surgeons; and that these two specialties are identical with respect to breast lump examination and diagnosis.” The threshold question of admissibility is governed by the scope of the witness’ knowledge and not the artificial classification of the witness by title. Photocopying and distributing this PDF of the Instructor's Manual is prohibited without the permission of Health Administration Press, Chicago, Illinois. For permission, please fax your request to (312) 424-0014 or e-mail hap1@ache.org. 7 Our appellate courts have had occasion to address this issue since that case.... The common thread tying these decisions together is that where the evidence indicates that the specialties overlap and the applicable standard of care is common to each, a medical expert from either of the overlapping groups who is familiar with that common standard is competent to testify as to the standard of care. Connecticut has not previously considered whether an orthopedic surgeon can testify as an expert against a podiatrist in a malpractice action. Other jurisdictions, however, have addressed this issue, reaching varying decisional results. The Ohio Supreme Court, citing a Connecticut case, held that the plaintiff’s medical expert, a podiatrist, was competent to testify as to the alleged malpractice, applying and failing to remove a cast which was too tight, by the defendant orthopedic surgeon. The record disclosed that the application and removal of casts is an area where these fields of medicine overlap. The court, therefore, concluded that the podiatrist was qualified to testify as an expert. The Georgia Court of Appeals addressed this issue, holding that where the evidence indicates the fields overlap and the methods of treatment are the same for the schools involved, an orthopedic surgeon can testify as an expert as to the standard of care which must be exercised by a podiatrist. The California Court of Appeals has addressed the analogous issue of whether a podiatrist can testify as to the applicable standard of care of an orthopedic surgeon performing foot surgery, holding that he can. The record revealed a familiarity with the surgery and contained testimony that the fields overlapped. There is, however, a line of authority excluding such testimony. The South Carolina Court of Appeals has held that an orthopedic surgeon was not competent to testify as to the applicable standard of care in a malpractice action against a podiatrist. The record there revealed that the orthopedic surgeon had never performed ambulatory foot surgery nor was he familiar with the surgical procedure performed. Likewise, the North Carolina Court of Appeals has excluded the testimony of an orthopedic surgeon on the applicable standard of care in a malpractice action against a podiatrist. The record also revealed an unfamiliarity with the field of practice. The Illinois Supreme Court has considered whether “a plaintiff may establish the standard of care a podiatrist owes a patient by offering the testimony of a physician or surgeon, or another expert other than a podiatrist.” The court held that “in order to testify as an expert on the standard of care in a given school of medicine, the witness must be licensed therein.” The dissent casts this as a mechanical and formalistic resolution of the issue. The decisions allowing and excluding expert testimony in this area generally focus on the expert’s familiarity with the school of medicine and the procedures involved. To resolve this issue in the context of this case requires an examination of the testimony proffered to qualify Weil as an expert, in order to determine whether he possessed a sufficient familiarity with the school of medicine and the procedures involved. In the absence of the jury, Weil was extensively examined regarding his qualifications to testify as an expert. He testified that he has performed hundreds of operations on the feet, that he was familiar with the surgical procedure performed on the plaintiff’s feet, and that he was familiar with the treatment, both conservatively and surgically, of keratosis and calluses upon the feet. Further, he testified that he had worked with almost all of the podiatrists in the New Haven area. They had referred patients to him for treatment and he had referred patients to them, generally for conservative treatment, but occasionally for surgical procedures performed in a hospital. He had observed and performed operations where more than one head and neck of a metatarsal was removed for neurological disorders of the feet. Here, the defendant podiatrist removed the fifth metatarsal of the plaintiff’s left foot. In addition, the doctor testified that he had performed implant operations and was familiar with implants into the foot and toes, but had never performed an implant operation on the toes. He stated that he was familiar with the standard of care applicable to the treatment of keratosis and bunions and that the standard of care did not change simply because a podiatrist rather than an orthopedic surgeon treated the patient. Photocopying and distributing this PDF of the Instructor's Manual is prohibited without the permission of Health Administration Press, Chicago, Illinois. For permission, please fax your request to (312) 424-0014 or e-mail hap1@ache.org. 8 The defendant podiatrist testified that, in terms of foot surgery, orthopedic surgeons and podiatric surgeons generally performed the same procedures. He admitted that a certain medical text on surgery on the feet was authoritative. Weil expressed a familiarity with that text insofar as it pertains to the plaintiff’s preoperative condition and the surgical and conservative nonsurgical techniques for the treatment of the plaintiff’s condition. Although Weil had never performed or assisted in the surgical procedures involved in the treatment of the plaintiff’s malady, this was so because he questioned the use of such procedures. The extensive offer of proof discloses that the plaintiff’s expert had the requisite familiarity with the particular school of medicine and the procedure involved to substantiate that he had the necessary qualifications to give his opinion as to the standard of care. There is error, the judgment is set aside and a new trial is ordered. Discussion Questions 1. What might have been the practical effect for the practice of podiatry if the decision in Marshall had been the opposite? 2. Do you believe it is fair to allied health professionals that they be judged by the standards of MDs? Suggested Answers 1. It would be hard for them to lose a malpractice case because plaintiffs would have to find other podiatrists as expert witnesses, which would be unlikely. 2. Sure. It’s the same part of my anatomy, regardless of who’s working on it or what school of medicine they ascribe to. Notes 1. S. Novak, Honorable Justice: The Life of Oliver Wendell Holmes 148 (1989). 2. Id., p. 157. 3. Id. The quote in the first full paragraph is from a Holmes law review article written earlier that year. 4. Id., p. 159. 5. O. Holmes, The Common Law 1 (1881). Photocopying and distributing this PDF of the Instructor's Manual is prohibited without the permission of Health Administration Press, Chicago, Illinois. For permission, please fax your request to (312) 424-0014 or e-mail hap1@ache.org. 9 Chapter 3: Negligence 1 General Principles of Negligence • What is a “tort”? • A civil wrong not based on contract – Usually based on “fault” – Strict liability uncommon in healthcare – Intentional torts in Chapter 2 • Elements El t – – – – Duty Breach Injury Causation 2 Elements of Negligent Tort • Duty – How to establish? – Published standard of care – “Due care in the circumstances” • foreseeability • reasonable person • Breach of duty • Injury j y • Causation 3 Misc. Thoughts • “Locality rule” • “Respected Respected minority” minority rule • Respondeat superior vs. independent contractor • Tort reform 4 A “structured settlement” $1 million Annual cost Reversionary trust $$ 0 Age 72 5

© Copyright 2025