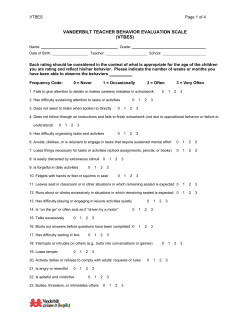

2 Traits and Individual Difference Variables Scales Related to Interpersonal Orientation,