ESP TECHNICAL MANUAL WWW.EMERGENETICS.COM ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014

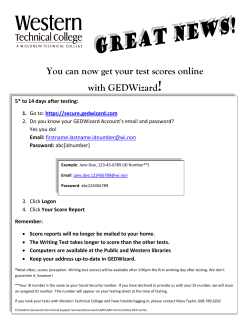

ESP TECHNICAL MANUAL WWW.EMERGENETICS.COM ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 Introduction to the Motivators This manual outlines the process followed to ensure the sound and ethical use of tests whether used for development, hiring, promotion, or placement. The manual has two sections: • Section 1 includes a summary of best-practices as published in the 1999 Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing.* • Section 2 outlines specific processes and procedures that were followed in developing the survey of Attitudes, Interests and Motivations. *1999, American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association & National Council on Measurement in Education American, Educational Research Association: Publisher, Washington, DC. Section 1 The (1999) Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing The Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing were developed to assure the fair and equitable use of tests. It outlines best-practice standards for testing, starting with the rationale for developing a test and ending with recommendations for its proper use. The major provisions include: • Establishing Validity…a test developer should accumulate scientific evidence to support the recommended use of test scores. In essence, the test should accurately measure what it is purported to measure. • Types of validity may include: » Content-related … the themes, wording and format of the items, tasks or questions closely resemble activities on the job » Face … the test-taker agrees the test themes, wording and format of the items, tasks or questions are appropriate for the job » Criterion-related …test scores correlate with job performance of jobholders » Concurrent design… a study comparing test scores to current jobholder performance » Predictive design…a study comparing test scores to future jobholder performance » Generalization….when validity data gathered from one position is applied to another highly similar position • Determining Reliability…a test developer should demonstrate test items are related to their associated factors and that test scores are consistent over time. In essence, the test should deliver repeatable results from one administration to the next. • Types of reliability may include » Inter-item…the statistical relationship between a specific test item and the factor it is supposed tomeasure » Test-retest…the consistency of the test score from one time to the next PAGE 1 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 • Recommended Documentation…the “Standards” recommend the following documentation: » The intention and rationale for the test » A discussion of procedures used in development and revision » Explanation of the statistical processes used in development » Discussion of how scales, norms and scores were determined » Statistical studies showing relationships between test scores and job performance » Demographic composition of subjects when available » Explanations of test interpretation and use » Guidelines, recommendations and cautions for administering the test Section 2 Development of the Motivators Most organizations invest more time and effort choosing a $5,000 copier than choosing a $50,000 employee... I. QUICK FACTS 1. How long is it? 55 items, 8th grade reading level, about 15-20 minutes to complete. 2. What kind of items does it have? Depending on the version, short business-type statements that are answered using a 1 (never agree) to 4 (always agree) Likert scale, a 1 to 7 continuous scale, or a 1 to 6 Likert scale. 3. Why use this Likert scale? The scale was chosen to maximize stability and accuracy. The clearer the scale, the more accurate the test. For example, it is easier for a test taker to choose between “always agree” and “sometimes agree” than it is to choose between “always agree”, “usually agree”, “frequently agree” and “sometimes agree”. 4. How many factors does it measure? 10 factors, each having five questions (10 Motivators)…six factors address job fit, four address job attitude and the remaining five questions consist of a lie scale which is not scored or presented. PAGE 2 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 5. How were items developed? By gathering data from about 30,000 people in business, factor- analyzing their responses into “clusters”, examining which items best measured each cluster, giving the revised test to current jobholders, and statistically comparing test scores with on-the-job performance ratings. 6. How is the Motivators administered? Administrator sets up candidate with a test link, candidate clicks link to open and complete test, administrator views and prints scores. 7. How is it scored? Candidate scores are automatically compared against a normative sample of typical job applicants. Results are calculated into percentiles and then ranked from highest to lowest. 8. What are “good” scores? There is no “magic set” of correct answers. Good Motivators depends on each job; that is, the specific Motivators associated with high and low job performance. 9. Does a high Motivator score mean the candidate has job skills? No. Only an INTEREST IN USING the skills he or she has. For example, both Cliff Clavin (the TV character) and Albert Einstein might score high in Frequent Problem Solving, but only one has the skills to be a theoretical physicist. Contact us about other tools that measure skills. 10. How are “ideal profiles” set? I. A group of job experts discuss each Motivator item and decide whether scores should be low, medium or high. II. Performance ratings are collected from supervisors of current jobholders (not performance appraisals), jobholders complete a Motivators test, and ratings are statistically compared to Motivator scores. 11. Is it legally credible? Yes, assuming you set profiles as indicated above. 12. Is it accurate? Yes. The test combines applicants’ responses to questions and compares the tally to a normative population. Simply put, if the applicant provides high answers to five different questions about liking to solve problems, we could conclude they like to solve problems. (Assuming you have not told them that problem solving is important) PAGE 3 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 13. Can an applicant fake the test? Almost any test can be faked. The test is normed on an applicant database, meaning that it takes into account the fact that applicants tend to try to make themselves look better. 14. How should I use the Motivators? • NEVER show an applicant the test scores. That would be unprofessional and take too long to explain. • • ONLY compare the applicant’s scores to the targets you identified with the job experts • DECIDE whether the answer would help or hinder the applicants’ predicted job performance. VERIFY disparate scores by using “extreme-type” questions like, “There are jobs that range from requiring considerable problem solving to ones that are fairly routine. Which types of jobs do you prefer and why?” 15. Is it EEOC “Compliant”? Trick question. The EEOC does not “certify” tests or test use. Every test user is encouraged to ensure his or her tests are job related and that scores accurately predict job performance. Contact us is you need assistance with this. 16. Can the Motivators be used for training? We don’t recommend it. The Motivators were developed to predict job performance as part of a comprehensive hiring system. It is not a training test. 17. How many people are in the current Motivators data base? The number varies. Feelings about work and work values tend to change over time. Norms are continually adjusted every few years to account for gradual social shifts in the way the applicants respond. 18. How many people are in the entire Motivators development base? Somewhere around 30,000 to 40,000. However, we only use the most recent scores to build norms. PAGE 4 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 II. ATTITUDES, INTERESTS AND MOTIVATIONS In spite of the need for high performance, research shows that there are still major differences in productivity among employees. Adrian Furnham wrote that variance in productivity across workers averages about two to one: that is, good workers produce about twice the output of poor workers. In the weaving industry, for example, good workers produce 130 picks per minute compared to poor workers’ rate of 62 picks per minute (the same ratio was found among hosiery workers, knitting machine operators and taxi drivers). As the work becomes more complex, the productivity ratio becomes even higher, so that a good physicist produces much more than twice the output of a poor one (Furnham, 1992). In the selling profession, good sales people are estimated to be more than twice as productive as poor ones (Schwartz, 1983); and, about one-half of sales people have no ability to sell at all (Greenberg and Greenberg, 1983). Among American managers, the estimated incompetence rate ranges between 60% and 70% (Hogan, 1990). In the insurance industry, the agent failure rate averages about 50% the first year and about 80% over three years. In retailing, good store managers have lower staff turnover, less inventory shrinkage and greater profitability than poor managers. In our own studies, approximately 80% of the safety engineers in a major public utility showed significant need for improvement in their ability to analyze problems. If the impact of selecting good people is so obvious, why are there are still major differences in performance among workers in so many positions and organizations? We believe critical areas of performance are overlooked when candidates are assessed for either internal or external positions. High Performance For years, selection experts have maintained that productivity improves when an applicant’s personality fits the organization’s style, culture, values, and strategies. For example, if a teamcentered organization were faced with a choice between two equally qualified applicants, common sense would dictate that the person who enjoyed working in a team environment would generally out-perform someone who liked working alone. Likewise, if an upscale bank wanted to deliver above average customer service to high-income customers, it would make sense for the bank to pick friendly service-oriented people. In fact, selection research confirms that when an individual’s task skills (i.e., knowledge, skills and abilities or “Aptitudes”) are combined with contextual skills (i.e., personality-based attitudes, interests, and motivations or “Motivators”) the quality of the selection process is significantly enhanced. For example: • When compared to selection based only on Aptitudes, adding Motivators such as Innovation and Creativity and Frequent Problem Solving improve the validity of hiring decisions (Kinder & Robertson, 1994). • In a meta analysis of 25 years of personality and performance research drawn from 117 studies of managers, professionals, sales people, skilled, and semi skilled workers, researchers concluded that extroversion predicted success in management and sales; openness to experience predicted training ability; and, conscientiousness correlated with success in sales, management, professional, skilled and semi-skilled positions (Barrick and Mount, 1991). • Adding personality items to the selection decision provides a more valid and enduring measurement of learning, development, and future performance (van Zwanenberg & Wilkinson, 1993). PAGE 5 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 • People perform better when an organization’s situational norms and values meet those they believe are important (Diener, Larsen, & Emmons, 1984). • The result of good “fit” between job and person increases the chances of high productivity, increased satisfaction, and positive attitudes that can contribute to organizational success (Ostroff, 1993). • People with the right personality fit tend to be more rewarded by the organization (Furnham & Stringfield, 1993). Stability Attitude, interest and motivational factors are stable and slow to change. Their endurance has been verified over periods ranging from 16 months to five years regardless of employer or occupation. Even adolescent pre-dispositions predict job satisfaction years later (George, 1992). Furthermore, in a study of single-egg twins reared apart, psychologists concluded that approximately 30% of the observed variance in job satisfaction was due to genetic factors (Arvey, Bouchard, Segal, & Abraham, 1989). The stability of Motivator factors makes them exceptionally difficult to change and extremely important to measure before making a hiring decision. Job and Task Motivation What Motivator personality factors are best? It depends. There is not one single set of Motivators that work for all organizations, tasks, and positions. Cultures vary from organization to organization, jobs vary from one department to the next, and management practices tend to vary with the manager (Furnham, & Stringfield, 1993; Ostroff, 1993). In addition, our own research shows that different combinations of Motivators affect different tasks. For example, the Motivators associated with teamwork are different from Motivators associated with overall performance. The most accurate Motivators are based on specific jobs, tasks, and organizations. Defining Attitudes, Interests and Motivations Motivators cannot be modeled only on high performers. High performance Motivators are only part of the selection puzzle. The real value of Motivators includes their ability to predict both high and low performance among equally skilled people. Building a Motivator model based exclusively on high performers ignores Motivator factors potentially associated with low performance – a major oversight that can lead to frequent hiring errors. Because specific aspects of an organization’s culture, values and strategies affects selection of applicants, prospective employees should be carefully chosen to achieve an optimal “range” of productivity that maximize organizational performance while minimizing dissension or motivation problems (Graham, 1986). Once a baseline set of Motivators is established, slight tailoring will avoid hiring “cloned” associates who may be unable to adapt to changing conditions. When the right Motivator personality factors are matched with the right Aptitudes in the right jobs, everyone benefits. PAGE 6 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 III. DEVELOPMENT Early development of the basic Motivator factors began with collecting a wide range of data from tens of thousands of male and female subjects employed in positions ranging from truck drivers to presidents. This research resulted in a generalized set of seven factors that could easily be understood and applied without a lot of technical explanation. We classified these factors into four thinking styles (information processing) and three behavioral styles (interactions). The early survey was not intended to be a complete theory of personality, but to explain a normal range of business behaviors. They included: • • • • • • • Conceptual unconventional, creative, unique, innovative Analytical problem solving, analysis, mathematical, investigative Structural rule following, administrative, structured Social social, concerned, friendly, interactive Assertiveness risk taking, driven, assertive, forceful Expressiveness social, outgoing, gregarious, extroverted Flexible easy, accommodating, easy going, cooperative The original model avoided complex psychological terminology, was simple to use, and easy to apply. Over succeeding years, the utility of the original profile Motivators was confirmed in advertising research, creativity workshops, team membership, selecting focus group members, communications workshops, and employment counseling. However, while the profile worked well as a tool for understanding thinking and behaving, it was not designed to predict job performance. To become a valid and reliable performance measurement tool, the profile needed significant revisions to measure traits associated with job effectiveness. To this end, a thorough search of the selection literature was conducted to determine how the original factors should be modified. Major sources of research that captured the redesign goals included work done by Williams (Williams, 1989; Holland (Holland, 1985); Hogan, Raskin and Fazzini (Hogan, Raskin & Fazzini 1990); and Barrick and Mount (Barrick & Mount, 1991). Holland’s work is well respected for its merger of job characteristics with personality types and is among the most widely accepted and used occupational counseling in the United States. Holland proposed jobs and the personalities of people performing those jobs could be clustered into six different personality areas. He called these areas Realistic, Investigative, Artistic, Social, Enterprising, and Conventional. Realistic jobs and realistic personalities included risky, practical, conservative, frank, and tangible factors. Investigative jobs included exploration, understanding, scientific, and research. Artistic jobs included creativity, openness to experience, intellectual, and innovative interests. Social jobs included helping, teaching, agreeableness, and empathy. Enterprising jobs included status, persuasion, directing, and gregariousness. Conventional types included routine, standards, practical, and orderly procedures (Gottfredson & Holland, 1991). PAGE 7 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 Table 1 shows correlations between the seven profile factors and Holland’s RIASEC taxonomy of job and personality combinations (N=37). Table 1 Profile Factors and Holland Factors Although the seven original factors fit Holland’s RIASEC taxonomy, there was little evidence that indicated Holland’s job-fit model predicted job performance. Further literature review showed that a different series of traits were associated with performance. For example: • Barrick et al., examined 117 studies of personality and performance to show that conscientiousness consistently predicted performance • Hogan et al. reported that researchers at both the Center For Creative Leadership and Personnel Decisions, Inc. found that failed or failing managers were often perceived as vindictive, selfish, and untrustworthy (Hogan, Curphy & Hogan, 1994) • Williams verified that risk taking and dominance was substantially correlated with performance in some sales positions (Williams, 1989) • Furnham linked a wide body of related personality factors to selection (Furnham, 1992). The following tables (N=97) show the convergent and discriminant correlations between the Motivator factors and the “Big 5” factors as measured by the NEO-FFI. The NE-FFI was developed by Paul Costa and Robert McCrae based personality research conducted in the 1950’s showing that all personality factors tend to cluster into five general factors. The B-5 model is well-respected, widely researched and extensively used for vocational counseling, mental illness and behavior, defining coping systems, and the like. Development, reliability and validity of the NEO-FFI is discussed in the NEO-PI Professional Manual. Convergent and discriminant correlation analysis with a well-established instrument purporting to measure similar constructs is often used to establish construct validity for a new instrument. That is, the seven EP factors and the NEO-FFI factors should have statistically significant correlations between similar personality constructs and discriminant (i.e., small, insignificant, or nonexistent) correlations between dissimilar constructs. Correlations shown in Tables 1 through 6 are significant at the .05 level or better. Correlations in Tables 7 through 18 are significant as noted. PAGE 8 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 Table 2 Analytical Factor Table 3 Structural Factor Table 4 Extraversion Factor Table 5 Conceptual Factor PAGE 9 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 Table 6 Social Factor Table 7 Assertiveness Factor Table 8 Willingness to Change Factor Table 9 EP and NEO-FFI Factors PAGE 10 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 As can be observed from these tables, the Emergenetics Profile shows strong convergent and discriminant correlations with both the NEO-FFI sub-factors and the main factors. This pattern provides evidence of construct validity. Additional tables are shown below. Table 10 EP and NEO-FFI Neuroticism Sub-Factors Table 11 EP and NEO-FFI Extraversion Sub-Factors Table 12 EP and NEO-FFI Openness Sub-Factors PAGE 11 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 Table 13 EP and NEO-FFI Agreeableness Sub-Factors Table 14 EP and NEO-FFI Conscientiousness Sub Factors After several iterations using approximately 150 subjects chosen from different organizational settings, factor-analytic results showed the seven revised profile scales remained robust while three new performance factors emerged. The resulting ten factors were validated using inter-item analysis and organized into ten homogenous-item composite (HIC) scales that, in various combinations, could be associated with both job fit and job performance. Each HIC contained seven distinct responses written to an eighth grade level and scored on a Likert scale. Anchor descriptions on the Likert scale were chosen based on the Bass, Cascio and O’Connor research to minimize the percentage of response overlap (Bass, Cascio & O’Connor, 1974). PAGE 12 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 IV. INTER-ITEM RELIABILITY AND FACTOR CORRELATIONS Overall split-half and inter-item reliability analysis was conducted on the test content. Correlations ranged from .72 to .91 as measured by Cronbach’s Alpha. Results are shown in Table 3. Table 15 Inter-Item Alpha Scores Convergent and discriminate relationships between the factors were also examined. Results are shown in Table 4. Table 16 Convergent and Discriminate N=579 ** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (1-tailed). * Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (1-tailed). PAGE 13 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 The ten Motivator factors should be considered “building blocks” suitable for screening applicants based on personal work preferences; however, on-the-job behavior is seldom that pure. More often than not, job-specific behavior is comprised of many behavioral elements. This can be shown when the basic ten Motivator factors are factor-analyzed and individual elements rationally organized into homogenous item composites. The compound factors are only reported in some versions of the Motivators to help clients better understand how the individual Motivator factors might be observed in job performance. The following table shows how the basic ten Motivator factors combine into job-related behaviors: Table 17 Compound Factor Combinations DESCRIPTION OF THE BASIC 10 MOTIVATOR FACTORS Frequent Problem Solving (FPS) This factor provides information about a person’s attitude toward solving complicated problems. People with high scores tend to prefer jobs that require a mental challenge and enjoy using their minds to solve complex problems. Positions that do not provide a mental challenge may prove boring to people who score high on this factor, while mentally challenging positions may intimidate people with low scores. Sample Item: I enjoy the challenge of solving a logical problem. Innovation and Creativity (IC) Not everyone likes jobs that require freethinking and creativity. Some people just want to produce a steady stream of traditional work. On the other hand, some organizations expect their people to continually generate new and better ways of producing work. It would be de-motivating to put a person with high creativity interests in a position requiring repetitive, unchanging work. Sample Item: I’m known for my unconventional solutions to problems. Desire for Structure (DfS) There are many jobs that require methodical administration and follow through to see that tasks are accomplished on time and on schedule. The traditional middle management position requires maintenance and oversight of systems. Other jobs require a more freewheeling style such as sales or positions that require making up rules as you go. Sample Item: I like to play it safe and go by the book. PAGE 14 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 Willingness to Change (WtC) Some jobs are steady while others change from day to day. People who thrive on fast pace and change enjoy jobs that challenge them to keep pace, while people who prefer stability would burn out with the pressure. This factor indicates a person’s adaptability to change. Sample Item: I don’t like jobs where there is a lot of pressure. Compete and Win (CW) Being self-centered can be very damaging for both the organization and co-worker relationships. Self-centered people spend much of their time thinking about themselves and the impact of decisions on them personally instead of worrying about out producing and outsmarting the competition. People with high scores on this scale indicate that they focus more on themselves than others. Sample Item: I’m not above using people to get my way if I feel I’m right. Close Personal Relationships (CPR) Teamwork has been linked to success in many organizations; however, managers are often surprised to find that some people prefer to work by themselves. People who enjoy working in teams are naturally more productive and satisfied when working closely with other people. People who like working alone are more productive working by themselves. Sample Item: I prefer jobs with close teamwork and cooperation. Expressive and Outgoing (EO) There are many jobs that require outgoing personalities, such as selling, management, public relations, or jobs that require positive public contact. People who score high on expressiveness label themselves as outgoing and having many social contacts. Low scores indicate the person may not have the interest or willingness to stand out in social settings. Sample Item: It is easy for me to start a conversation with a stranger. Quick Decisions (QD) Jobs that require fast decisions and quick actions require people who enjoy that type of environment. Too much impulsiveness, however, can lead to the “ready, fire, aim” syndrome. Some people are driven to knee jerk reactions that get them into trouble because they did not think through the consequences of their actions. Sample Item: Getting a job done is more important than how it is done. Need to be Perfect (NtbP) A small amount of perfectionism goes a long way. People with high perfection scores may never be satisfied enough with the final product causing unnecessary delays and reductions in output. People with too little perfectionism may be sloppy and unconcerned with quality. Sample Item: I insist on taking time to perfect a project. Priority of Job (P) For some people, the office is a battleground between good (the employees) and evil (the management). These people are either unable or unwilling to pull together for the common good or focus on the primary importance of the customer. Their attitudes sap energy and become destructive to both morale and productivity. Sample Item: It is OK to take long lunches and breaks if you are underpaid. In addition to the ten personality factors listed above, an imbedded lie scale was added to help assure reliable responses. PAGE 15 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 V. VALIDATION STUDIES Traditional Predictive Criterion Validation Studies Study 1 Position: Outbound Market Research Raters: Supervisors using an overall three-point scale (low, average, high) Test: Motivators Level Two (10 factor scores + consistency scale) Number: 139 people Correlation type: Spearman’s Rho Table 18 Study 1 Study 2 Position: Inbound order taking Raters: Supervisors using a ten-point scale for skill acquisition, a two-point scale for summary performance and a three point scale for overall performance Test: Motivators Level Two (10 factor scores + consistency scale) Number: 45 people Correlation type: Spearman’s Rho Table 19 Study 2 PAGE 16 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 Combined Studies The next table is a compilation of about 5000 surveys from several different companies comparing Motivator scores with performance ratings. It shows the uncorrected correlations between different Motivator factors and people already on the job. All numbers reported here are statistically significant at the P<.05 or p<.01 level. Non-significant data is blanked. Table 20 Combined Studies PAGE 17 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 Demographic Differences The next three tables show Motivator average scores when “filtered” by demographics. The tables below show demographic differences in average scores for age, race and gender. Table 21 Demographic Differences PAGE 18 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 VI. GUIDELINES AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR USE Guide to Setting Motivator Scores Motivators help scientifically identify people who prefer to think and act in certain ways. If two applicants have equal skills, the person whose thinking and acting preferences meets job requirements will generally outperform the other. Although the Motivators measure a broad range of attitudes, interests and motivations, you could think it as simply being a “motivation measure.” Motivators Vary With Job and Task What Motivator personality factors are best? It depends. There is not one single pattern of Motivators that work for all organizations, tasks, and positions. Cultures vary from organization to organization, jobs vary from one department to the next, and management practices tend to vary with the manager. In addition, our own research shows that different combinations of Motivators affect different tasks. For example, the Motivators associated with teamwork are different from Motivators associated with overall performance. The “best” Motivators scores are based on specific jobs, tasks, and organizations. Motivators Are Not Just Based on High Producers It is major mistake to model Motivators on only high performers. High performance Motivators are only part of the selection puzzle. The real value of Motivators includes their ability to predict both high and low performance. Building a Motivator model based exclusively on high performers ignores the Motivator factors potentially associated with low performance – a major oversight that can lead to major hiring errors. Because specific aspects of an organization’s culture, values and strategies affects selection of applicants, prospective employees should be carefully chosen to achieve an optimal “range” of productivity that maximize organizational performance while minimizing dissension or motivation problems. Once a baseline set of Motivators is established, slight tailoring will avoid hiring “cloned” associates who may be unable to adapt to changing conditions. When the right Motivator personality factors are matched with the right Aptitudes in the right jobs, everyone benefits. Motivators are NOT Skills Motivator scores are self-report. Although we make every effort to minimize faking, a Motivators score only has about a 2% to 8% relationship with “ability”. For example, both Albert Einstein (a famous physicist) and Cliff Clavin (a Cheers TV character) may both have high problem solving interests, but we know that Cliff has neither the education nor the skills to be a theoretical physicist – that takes a separate kind of test. Managers should remember that high performance only happens when a person’s job skill and job motivation are equal to job requirements. So, then, how do you go about setting Motivators scores? Step One: Discuss with job holders (not managers) the definition of each Motivator factor. Job holders know the most about the job. Collectively decide if the Motivator score should be low, middle or high. Remember, “good” is not high or low –“good” is what fits the job. Use the chart below to guide the discussion. Circle the target scores described by the job experts. PAGE 19 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 Table 22 Which Factors Match the Job? Now determine if these factors make any difference in performance. For example, if Low Quick Decisions was associated with the job, do high performers tend to be slow and precise (e.g., have low impulsiveness) and are low performers fast and impulsive? Review the last table and ask the group which factors make the difference between high and low performance. Use the Table below and circle the “job-critical” Motivators with a red pen and circle the “nice to have” Motivators with a blue pen. PAGE 20 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 Table 23 “Job-Critical” versus “Nice to Have” Motivators Interpreting Scores • The ten Motivator factors are directly related to job performance. Independent research shows these factors are highly stable over time. They are not intended to be “training” or “coaching” guides…The priorities you see in Motivators results are generally the priorities you get on the job. • Motivators are not skills. They are applicant’s attitudes, interests and motivations about whether to use the skills they have… Think of them as the “will do” part of the job. • Every factor score is calculated from responses to 5 statistically-related individual questions. This reduces the effect of any single question on an overall factor score. • Each factor score is normed based on an applicant data base. This both minimizes applicant attempts to “look good” and allows employers to compare an individual applicant to a population norm. Ignore raw scores…the information is in the norms! • Individual Motivators factors are not-position specific. For example, our research shows applicants for a highly technical position generally have the same score range of Frequent Problem Solving as applicants for an executive or customer service position. • The Motivators are hard to fake. The applicant would have to know which questions load on each factor, the norms for each factor, which items were in the reliability scale, and the overall pattern required for the job. • The patterns and strength of the applicant’s Motivator factors provide the most critical information. PAGE 21 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 Priorities Score The Priorities score evaluates applicants’ willingness to put job goals ahead of personal goals. A person with high “Work Primacy” is willing to work overtime, work weekends, and make sacrifices for the job. Because these items are “transparent”, we expect applicants to score high. In general, all scores should be above 50%. Scores above 50% are indicated by a green check mark in candidate results. Work scores below 50% indicate a low job priority and are indicated in candidate results by a yellow exclamation mark. We advise extreme caution with these scores. Patterns Now, it’s time to examine patterns. Common sense tells us high job performance requires two things: 1) an ability to do the job; and 2) willingness. Ability without willingness leads to underperforming employees. Willingness without ability leads to employees who make mistakes. Motivator patterns show employers something applicants are reluctant to share in an interview: job willingness. Now that we have excluded Reliability and Work scores, look at the top three Motivator scores. These are things the applicant really “likes to do”; the bottom three Motivators as things they really dislike; and ones in the middle as “take it or leave it”. • • • Top 1/3 = Strong Preference Middle 1/3 = “Take it or Leave it” Bottom 1/3 = Don’t like it The following five examples are “stereotypical profiles” intended to give clients ideas about how the Motivators work together to predict behavior. In our experience, there can be substantial differences between one job and the next, even though they might have the same title. Therefore, we encourage every organization to set specific internal standards. If you need help setting standards, we will be glad to work with you. PAGE 22 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 This pattern tells us the position requires a great deal of emphasis on details and quality work. The applicant will need to go by the book and follow (or implement) defined procedures. They will be asked to address various problems throughout the day. This position will very much be an individual effort, with little to no team or social contact. It also requires that the applicant be fairly inflexible--in combination with the Desire for Structure at the top, this means always stick to the rules. This position requires a high level of extraversion and competitive spirit. The applicant needs to enjoy finding solutions to problems in order to reach goals. Winning is critical to this position. The applicant need not get caught up with details and will not be working in a particularly structured environment. It’s helpful if they are reasonably inflexible--in combination with Compete and Win, they need to make the sale, but not give away the farm in doing so. PAGE 23 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 For the Sales Farmer position, we’re looking for someone to build and maintain relationships with clients. The applicant must enjoy helping the client solve problems and should have a flexible attitude in meeting those needs. The position needs someone who won’t get too caught up with nit-picky details and who can work in an unstructured environment. Lastly, we aren’t looking for someone to make snap decisions, but rather, to work thoroughly through problems with the clients. Note that even though this is more of a relational sales role, Compete and Win is still fairly high. This Manager position requires that an applicant to be very team oriented; devoted to building relationships with co-workers. This is someone who thrives in a structured environment where they are asked to deal with numerous problems on a daily basis. The position requires deliberate decision making and is not one that encourages a competitive drive. The applicant need not be focused on small details as this position asks for a “big picture” perspective. PAGE 24 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 This Inbound Customer Service role needs to be filled by someone who really enjoys problem solving as well as constant contact with clients. The applicant needs to be flexible in dealing with client needs, and does need to have a reasonable level of interest in building and maintaining relationships (Close Personal Relationships is ranked 4th). The applicant shouldn’t “speak first, think second”--they should take their time with customers and think thoroughly through decisions. With Need to be Perfect ranked 9th, the job-holder should not be overly concerned with minute details that could hold up the service process. Conflicts Experience shows some factors tend to cluster together while others are dramatically polarized. For example, here are the factors that usually “avoid” each other (i.e., as one score goes up, the other score goes down). “Weak”, “Mod”, or “Strong” refers to the strength of the avoidance. Caution is advised when these scores fall “near” each other. For example, a high score in Compete and Win and a high score in Willingness to Change is very unusual, as is a low score in Quick Decisions and a low score in Close Personal Relationships. Conflicting factor patterns may either indicate the applicant is internally conflicted or trying to fake the survey. In either case, we advise caution. Be careful not to confuse a Motivators score with ability. A Motivators score is a personal preference of how the person describes himself or herself compared to the norm of the general population. Research shows the correlation between being able to solve complicated business problems and a motivation for problem solving is only around 2%. The correlation between being interpersonally skilled and teamwork is only about 8%. PAGE 25 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 GUIDELINES FOR PROBING APPLICANT MOTIVATORS Motivators identify “hidden” areas an applicant may be reluctant to admit during an interview. They are not like the bathroom scale. The scale does not have a personal agenda. Motivators are always selfreports. We try to stabilize Motivators data by using five items to measure each factor, converting the score into a percentile that compares applicant’s scores with job applicants from a general population, telling applicants we will be verifying answers, and using rating words that minimize reporting error. High and Low Frequent Problem Solving Jobs fall into a wide spectrum. Some require ongoing mental challenge and never-ending problemsolving. Others are fairly routine and predictable. What have your past jobs been like? Which did you like best? Why? High and Low Innovation and Creativity Some jobs require some really off-the-wall thinking and creativity. Others are straightforward and no-nonsense. What have your past jobs been like? Which did you like best? Why? High and Low Desire for Structure Some jobs have a great deal of rules and regulations to follow, while others expect employees to be independent and take risks. What have your past jobs been like? Which did you like best? Why? High and Low Willingness to Change Some jobs seem to change from day to day, while others tend to remain constant over long periods of time. What have your past jobs been like? Which did you like best? Why? High and Low Close Personal Relationships Some jobs require you to work very closely with team members, even doing each others’ work; while others require working alone with minimal interaction with co-workers. What have your past jobs been like? Which did you like best? Why? High and Low Expressive and Outgoing Some jobs require you to be constantly outgoing and friendly with all kinds of people. Other jobs expect you to be reserved and controlled. What have your past jobs been like? Which did you like best? Why? High and Low Quick Decisions Some jobs require you move quickly and make decisions without much thought or preparation. Other jobs expect you to think through your actions carefully before taking action. What have your past jobs been like? Which did you like best? Why? High and Low Need to be Perfect Some jobs require you to be totally focused on details and produce perfect work all the time. Other jobs require high productivity regardless of the quality. What have your past jobs been like? Which did you like best? Why? High and Low Compete and Win Some jobs require you to be highly assertive, driven and competitive. Other jobs have a collaborative atmosphere where the team is more important than the individual. What have your past jobs been like? Which did you like best? Why? PAGE 26 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 VII. CORRELATION WITH HOMOGENOUS ITEM COMPOSITES (HICS) The basic Motivators survey provides basic motivation data at the 10-factor level, but not all motivation factors occur independently. For example, factor-analytical examination shows some factors naturally cluster together forming homogenous item composites (HICs). HICs are clusters of dissimilar factors that naturally tend to occur together. For example, the Frequent Problem Solving Motivator might represent a preference for engaging in challenging problems. In practice, however, a person might actually use a combination of Creativity to generate new ideas, Problem Solving to analyze them and Planning toassure effective implementation. This would represent a homogenous item composite that we might term “comprehensive thinking”. Data were collected from approximately 839 applicants and factor-analyzed to identify HICs that empirically and rationally clustered together. The data were varimax-rotated, scree plots were examined for eigenvalues greater than 1 and items were rationally extracted. The results are shown as follows: Table 24 Motivator Correlations with HICs Validity and reliability data is being gathered. PAGE 27 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 INTRODUCTION TO THE APTITUDES Emerging Job Complexity Many jobs in an emerging global economy are multiple-dimensioned. That is, employees are expected to perform jobs that require a broad range of skills such as written documentation, oral communication, identifying and managing details, solving problems, receiving voicemail, reading and responding to email messages, and quickly learning and applying new information. The dynamic nature of these jobs generated a major problem for organizations that wanted to quickly and efficiently measure applicant skills. Few, if any written tests are able to capture these activities and stand-alone computer simulations seldom deliver more than realistic job previews for a few specific positions. In response to the need for better pre-hire tools, data from hundreds of job analyses covering thousands of positions were examined for common activities associated with either success of failure. This review identified three major clusters of job competencies. 1. Communication…The ability to communicate and respond to principles, ideas and thoughts expressed by co-workers, managers and customers This is an essential element of performance that required employees to understand and spell common business-related words normally learned in contemporary high school English classes; to read and respond to emails; and, to review and retain information contained in voicemail messages. 2. Attention to Detail…The ability to quickly identify errors in numeric data. This skill is often associated with error checking, editing, proof reading, and order entry accuracy. It often involves working with numbers such as stocking units, inventory, accounting numbers and business reports. These numbers are often presented to the employee on a computer or automated workstation. 3. Problem Solving…As organizations increasingly shift toward automation and expanded job roles, problem solving and critical thinking has become a greater component of job performance. Employees are increasingly expected to learn on the job and make many decisions that were previously done by managers. Computer-Based Administration The worldwide proliferation of the internet has made computer-based operations an every day part of office work. Computerized test administration has also been shown to be an effective prehire testing methodology. Computers can simulate situations similar to those encountered in a typical organization: reading email, listening to voice mail and performing basic keyboard and screen navigation tasks to solve typical business problems. Computerized test administration provides a dynamic pre-hire testing environment that presents a candidate with series of carefully administered active and interactive exercises that measure major dimensions of performance. PAGE 28 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 SECTION 1 Overview of Aptitudes The Aptitudes battery includes five exercises that present the candidate with content and criterion validated items in a timed format. Three of the tests are delivered in typical question and answer format. The fourth and fifth tests are delivered concurrently to evaluate the candidate’s ability to multi-task. Attention to Detail Exercise The candidate has two minutes to examine 20 sets of three numbers and identify duplicates. This exercise is content valid for jobs that require comparing numbers, completing forms accurately, examining written data for inaccuracies, and other tasks requiring an ability to recognize subtle differences in information. Item example: A company assigns SKU codes to each of their products. A valid code should contain three, different 7-digit numbers (i.e., numbers cannot be duplicated). Examine the following SKU numbers and identify which ones contain duplicates: Business Vocabulary Exercise (Part of the Communication Section) The candidate has 5 minutes to read and decide which of 40 words are misspelled. If a word is misspelled, the candidate is asked to spell the word correctly in the blank space provided. Words were chosen from commonly misspelled business-related, high school vocabulary lists. This exercise is appropriate for jobs that require correct spelling. Example: PAGE 29 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 Understanding Communication Exercise (Part of the Communication Section) The candidate has 5 minutes to review 22 business-related statements and decide what they mean. Words were chosen from high school vocabulary lists. This section is appropriate when it is important for employees to have a broad vocabulary. Example: Mary’s boss told her to be discreet about the plan. That means Mary: 1. Should be cautious 2. Must tell others 3. Should volunteer her thoughts 4. Could make a decision 5. None of the above Multi-Tasking Section The candidate is given a total of 30 minutes to complete two separate tests delivered concurrently on the same computer screen. On one side of the screen, the candidate is asked to solve as many of 20 business-related problems as possible in the time allowed. Concurrently, on the right side of the screen, they receive 20 notifications announcing the arrival of email messages. Interspersed between the email items are 20 questions about information contained in prior emails. The multi-tasking section evaluates the candidate’s ability to effectively solve problems in an active multi-tasking environment. Problem Solving Example: You take an inventory of office supplies every week. You noticed that 60 memo pads were used during the first week of August. On the average, how many memo pads were used each day that week? 1. 60 2. 50 3. 15 4. 12 5. none of the above PAGE 30 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 DEVELOPMENT OF THE ITEMS The Aptitudes items were developed over a period of two years by examining job analysis reports at the content-level. This analysis identified three criterion skill domains that applied to a wide range of jobs. These domains included verbal and written communication, paying attention to small details and solving problems while being distracted by emails and voice mails. Attention to Detail Section Many jobs require the jobholder to review data and discern small differences and discrepancies. This is especially true of job activities such as list-checking, comparing data, finding data entry mistakes, reading and interpreting information from computer screens, and so forth. Examining numerical data was a common element among a majority of jobs. To evaluate this domain, we developed a simple task that involved visually scanning a fictitious product code looking for differences and similarities between numbers. Comparing numerical data usually requires less computational ability than analyzing data or using mathematical operators to solve problems. Draft items were prepared and computer administered to jobholders in a wide variety of positions. The initial battery consisted of 5 minutes to evaluate 40 items. It was gradually reduced though successive trials and analysis to 2 minutes and 20 items. Items were retained only when 80% or less of the subjects answered the item correctly and less than 20% answered incorrectly. The following histogram shows the score distribution superimposed with a normal curve (AD = Attention to Detail). PAGE 31 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 Communication Sections Communication skills were evaluated using two sub tests: the ability to understand a statement and the ability to spell common business related words. Both batteries used words drawn from high school grade vocabulary lists. There were 45 initial draft items in the understanding communication battery and 41 draft items in the spelling battery. Draft versions of the test were computer administered to jobholders in a wide variety of positions. Though successive trials and analysis of scores, the time limit and number of items were edited and gradually reduced to 40 items and 5 minutes for the spelling subtest and 22 items and 5 minutes for the understanding communication subtest. Each item in the two communications exercises were also evaluated at the response level. The item was discarded if more than 80% of the subjects answered the item correctly or more than 20% answered incorrectly. The following histograms show the score distributions superimposed with normal curves for both sections (UC = Understanding Communication; BV= Business Vocabulary). PAGE 32 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 Multi-Tasking Section Multi-tasking -- the ability to accurately solve problems while being distracted by interruptions -- is present in many jobs. Modern day jobholders are consistently bombarded by emails, voice mails and questions while performing their daily activities. In spite of these diversions, they are expected to maintain clear thought and make accurate decisions. This section includes problems presented on one side of a computer screen while messages and questions are presented on the other. Items for the multi-tasking subtest were developed from common business scenarios identified by job analyses. They included functions such as analyzing data, making decisions and making routine business decisions. Items were developed to represent practical business problems requiring basic business math, data analysis and so forth. The draft test included 40 problem-related items and 40 email items. Through successive trials and analysis of scores, the time limit and number of items were edited and gradually reduced to 20 problem-related items, 40 email items and 30 minutes. As discussed in the previous sections, items in the multitasking section were discarded if more than 80% of the subjects answered the item correctly or more than 20% answered incorrectly. The multi-tasking section includes three scores: problem solving, emails and a weighted combination of Problem Solving and Email scores that represents the candidate’s ability to multi-task. The following histograms show the score distributions superimposed with normal curves for all three sections (Problem = Problem Solving; Email= Email; and MT=Multi-Tasking). PAGE 33 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 PAGE 34 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 SCORING There are many ways to score a test. These include opinion-based systems (i.e., someone independently chooses acceptable scores), job-validity systems (e.g., scores are set by statistically comparing applicant scores with current employee scores) and normative systems (i.e., applicant scores are compared to an independent database. We always recommend job-validated systems because comparing applicants with current employees who perform the same job yields the best results. However, because many organizations are reluctant to go through the rigor of a job analysis, by default, we norm scores using a broad base of independent applicants. This allows clients to objectively compare one applicant with another. We DO NOT recommend using opinion-based systems because of the potential for making wrong hiring decisions.. Scoring for all exercises is done by analyzing the number of items correct andEach applicant score is compariedng it to a norm of approximately 313 typical job applicants. The resulting number is reported in percentiles. allowing clients the opportunity to compare individual candidates with a typical applicant population. The following table shows the percentile distribution using a 20-point percentile scale. Statistics PAGE 35 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 VALIDATION Introduction Before organizations can use tests to make important hiring or placement decisions, they need to know that test scores have a statistical relationship with job performance. This process is called “validation”. In other words, high test scores predict high job performance. Validation There are five terms generally associated with test validation: face, content, construct, criterion, and generalizability. There are two terms generally used to define the design of a validation study: predictive and concurrent. They are defined below: • “Face” validity means that test-takers generally agree test items appear to be job-related. Face validity for the Aptitudes was determined during the early phases of test development when beta-testers were asked to comment about the job-relatedness of specific terms and factors. Objectionable items were deleted. • “Content” validity means the test content and test factors resemble the nature of the job. Content validity of the Aptitudes were determined through multiple job analysis and observation of business people working in either office or customer contact positions. Various sections of the Aptitudes include paying attention to details; spelling and understanding words and phrases based on a high school business vocabulary; and, performing problem solving tasks while being asked to read and recall information. We believe the Aptitude content represents a sample of typical job activities. • Construct validity refers to deep-seated mental constructs such as problem solving and motives. The Aptitudes were not designed to measure mental constructs. • Predictive and concurrent refer to whether data is collected from current jobholders (concurrent design) or from future job holders (predictive design). The Aptitudes were developed based on both applicant and employee populations. • “Criterion” validity means that test scores are statistically related to performance. However, there are many different ways to define “performance”. Sometimes performance is training pass-rates, other times it is subjective supervisory opinion and still others it is “end of the line” productivity. The following table shows data gathered from various productivity studies for various clients (all data is statistically significant at the p<.05 level) PAGE 36 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 Example Performance Correlations Drawn from Various Organizational Studies Comments on the table above: Organizations tend to use similar terms to define entirely different sets of performance ratings. This chart only illustrates that one or more Aptitude factors tend to correlate with different types of employee performance depending on how the company defines “important”. For example: • Understanding Communication is negatively correlated Sales/Hour (-.246), Clarity (-.305) and Performance Ratings (-.209) in some organizations, but positively correlated in another (.370). Since Understanding Communication scores are associated with general level of intelligence, this could mean that intelligent people take more time with clients and produce fewer sales as a result. • In another example, Performance Ratings are strongly correlated with both Attention to Detail (.390) and Business Vocabulary (.310) but not Communication, Problem Solving or Recall. The overall associations and correlation of the Aptitude scores thus depend on determining 1) clear causal relationships with the specific performance criteria (i.e., does high problem solving ability help or hinder sales productivity?); 2) an understanding that performance criteria might be confounded within an individual study (i.e., sales/hour might be positively correlated with Problem Solving, but negatively correlated with Attention to Details); and, 3) possible non-linear relationships with performance (i.e., there can be too little, just right and too much of a good thing). PAGE 37 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 The final validity factor is “generalization”. When two positions contain essentially the same content, it is possible to generalize the validity data gathered from one job to the other. As shown in the table of correlations above, different Aptitude factors tend to correlate with different aspects of job performance. The Aptitude battery is highly targeted toward specific job skills. We recommend establishing a clear causal relationship between performance and each Aptitude criterion domain. For example: We do not recommend using validity generalization with the Aptitude battery. CONTACT INFORMATION FOR ESP’S DEVELOPER R. Wendell Williams, PhD. Phone: 770-792-6857 Email: rww@scientificselection.com PAGE 38 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 TECHNICAL REFERENCES Arvey, R.D., Bouchard, T.J., Segal, N.L., & Abraham (1989). Job satisfaction: environmental and genetic compositions. Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 74, 187-192. Barrick, M.R. & Mount, M.K. (1991), The big five personality dimensions and job performance: a meta analysis, Personnel Psychology, Vol. 44, 1-26. Bass, B.M., Cascio, W.F., & O’Connor, E.J. (1974), Magnitude estimations of expressions of frequency and amount. Journal of Applied Psychology, 59 (3), 313-320. Bommer, W. H., Johnson, J. L., Rich, G. A., Podsakoff, P. M., & MacKenzie, S. B. (1995). On the interchangeability of objective and subjective measures of employee performance: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 48 (3), 587-605. Bray, D. W. (1982). The assessment center and the study of lives. American Psychologist, 37 (2) (February), 180- 189. Byham, W. C. (1992). The assessment center method and methodology: New applications and technologies. , 1-23. Carmelli,D., Swan,G.E., Roseman,R.H. (1990), The heritability of the Cook and Medly Hostility Scale revisited. Special issue: Type A behavior. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, Vol. 5(1), pp. 107116. Deiner, E., Larsen, R., & Emmons, R., (1984). Person x situation interactions: choice of situations and congruence response models. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Vol. 47, 580-592. Digman, J.M., (1990). Personality structure: emergence of the five-factor model. Annual Review of Psychology, Vol. 41, 417-440. DuBois, P.H., (1970). A history of psychological testing. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. Fleischman, E.A., (1975). Toward a taxonomy of human performance. American Psychologist, 30, 1127 - 1149. Furnham, A., (1992). Personality at Work: The role of individual differences in the workplace. London: Rutledge. Furnham, A. & Stringfield, P., (1993). Personality and occupational behavior: Myers-Briggs Type Indicator correlates of managerial practices in two cultures. Human Relations, Vol. 46, No. 7. George, J. (1992). The role of personality in organizational life: issues and evidence. Journal of Management. Vol. 18, No. 2, pp. 185-213 Graham, J. (1986). Principled organizational dissent: a theoretical essay. In Staw, B.M., & Cummings, L.L. (Eds.), Research in Organizational Behavior (Vol. 8, pp. 1-52). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Greenberg, J. & Greenberg, H. (1983, December). The Personality of a Top Salesman. Nation’s Business, pp. 30-32. Gottfredson, G.D. & Holland, J.L. (1991). Professional manual. The Position Classification Inventory. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc. Heath, A.C., Jardine ,R., Eaves, L.J., & Martin, N.G. (1989). The genetic nature of personality: genetic analysis of the EPQ. Personality and Related Differences, Vol. 10(6), 615-624. Hogan, R. Curphy, G.J., & Hogan, J. (1994). What we know about leadership: effectiveness and personality. American Psychologist, Vol. 49, No. 6, pp. 493-504. PAGE 39 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 Hogan, R., Raskin, R., & Fazzini, D. (1990). The dark side of charisma. In K. E. Clark & M. B. Clark, (Eds.), Measures of Leadership (pp. 343-354). West Orange, NJ: Leadership Library of America. Hogan, R. T. (1991). Personality and personality measurement. In M. D. Dunnette & L. M. Hough (Eds.), Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology (Vol. 2, 873-919). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press, Inc. Holland, J. L. (1985). Making Vocational Choices: A Theory of vocational personalities and work environments. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Kinder, A. & Robertson, I.T., (1994). Do you have the personality to be a leader? The importance of personality dimensions for successful managers and leaders. Leadership and Organizational Development, Vol. 15, No. 1, 3-12. Lord, R. G., & Maher, K. J. (1989). Cognitive processes in industrial and organizational psychology. In C. Cooper & I. Robertson (Eds.), International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology . New York: Wiley. Lykken, D.T., Tellegen, A.,& Iacono, W.G. (1982). EEG spectra in twins: evidence for a neglected mechanism of genetic determination. Physiological Psychology, March, Vol. 10(1), 60-65. Macan, T. H., Avedon, M. J., Paese, M., & Smith, D. E. (1994). The effects of applicant’s reactions to cognitive ability tests and an assessment center. Personnel Psychology, 47, 715-738. McHenry, J. J., Hough, L. M., Toquam, J. L., Hanson, M. A., & Ashworth, S. (1990). Project A validity results: The relationship between predictor and criterion domains. Personnel Psychology, 43, 335-354. Motowidlo, S. J., Borman, W. C., & Schmit, M. J. (1997). A theory of individual differences in task and contextual performance. Human Performance, 10(2), 71-83. Murphy, K. (1982). Difficulties in the situational control of halo. Journal of Applied Psychology, 67(2), 161-164. Motowidlo, S. J., & Van Scotter, J. R. (1994). Evidence that task performance should be distinguished from contextual performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79(4), 475-480. Neale, M.C., Rushton, J.P. & Fulker, D.W. (1986). Heritability of item responses on the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire. Personality and Individual Differences. Vol. 7(6), 771-779. Ostroff, C., (1993). Relationships between person-environment congruence and organizational effectiveness. Group and Organization Management. Vol. 18, No. 1, March, 103-122. Plomin, R., Lichtenstein, P., Pederson, N.L., McClearn, Gerald, E., et.al, (1990). Genetic influence on life events during the last half of the life span. Psychology and Aging, March. Raymark, P. H., Schmit, M. J., & Guion, R. M. (1997). Identifying potentially useful personality constructs for employee selection. Personnel Psychology, 50(3)(Autumn), 723-736. Rynes, S. & Gerhart, B., (1990). Interviewer assessments of applicant “fit”: an exploratory investigation. Personnel Psychology, Vol. 43, 13-35. Sackett, P. R. (1987). Assessment centers and content validity: Some neglected issues. Personnel Psychology, 40, 13-24. Sackett, P. R., & Dreher, G. F. (1982). Constructs and assessment center dimensions: Some troubling empirical findings. Journal of Applied Psychology, 67 (4)(401-410). Sackett, P. R., & Hakel, M. D. (1979). Temporal stability and individual differences in using assessment information to form overall ratings. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 23, 120-137. PAGE 40 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014 Schlesinger, L. (1991). Comments made while addressing the 1991 Instructional Systems Conference. Schwartz, A.L., (1983). Recruiting and Selection of Salespeople. In Borrow, E.E. & Wizenberg, L. (Eds.), Sales Managers Handbook (pp. 341-348), Homewood, IL: Dow Jones Irwin. Tett, R. P., Jackson, D. N., & Rothstein, M. (1991). Personality measures as predictors of job performance: A meta-analytic review. Personnel Psychology, 44, 703-742. van Zwanenberg, N. & Wilkinson, L.J., (1993). The person specification - a problem masquerading as a solution? Personnel Review. Vol. 22, No. 7, 54-65. Vernon, P.A., (1989) The heritability of measures of information processing. Personality and Individual Differences. Vol. 10(5), 573-576. Williams, R.W., (1989). Correlations between optimism, achievement, and production among stockbrokers (M.S. Thesis, Virginia Commonwealth University, 1989). Williams, R.W. (1998). Using Personality Traits to Predict the Criterion Space (Ph.D. Dissertation, The Union Institute, 1998) PAGE 41 ©Emergenetics LLC, 2014

© Copyright 2025