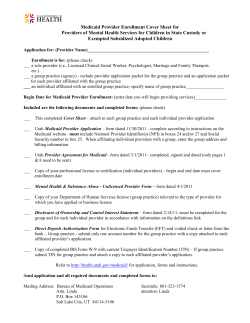

THE PENNSYLVANIA COMMUNITY HEALTH