Visual Outcomes in the Subfoveal Radiotherapy Study for Age-Related Macular Degeneration

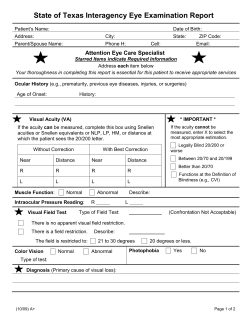

CLINICAL SCIENCES Visual Outcomes in the Subfoveal Radiotherapy Study A Randomized Controlled Trial of Teletherapy for Age-Related Macular Degeneration P. M. Hart, FRCOphth; U. Chakravarthy, FRCOphth, PhD; G. Mackenzie, PhD; I. H. Chisholm, FRCOphth; A. C. Bird, FRCOphth; M. R. Stevenson, MSc; S. L. Owens, MD; V. Hall, FRCR; R. F. Houston, FRCR; D. W. McCulloch, PhD; N. Plowman, FRCR Objective: To determine whether teletherapy with 6-mV photons can reduce visual loss in patients with subfoveal choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration. Design: A multicenter, single-masked, randomized controlled trial of 12 Gy of external beam radiation therapy delivered to the macula of an affected eye vs observation only. Setting: Three United Kingdom–based hospital units. Participants: Patients with age-related macular degeneration, aged 60 years and older, who had subfoveal choroidal neovascularization and a visual acuity of 20/200 (logMAR 1.0) or better. Methods: Two hundred three patients were randomly assigned to radiotherapy or observation. Treatment was undertaken at designated radiotherapy centers, and patients assigned to the treatment group received a total dosage of 12 Gy of 6-mV photons in 6 fractions. Follow-up was scheduled at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months. After excluding protocol violators, the data from 199 patients were analyzed. Main Outcome Measures: The primary outcome mea- sure was mean loss of distance visual acuity in the study eye at 12 and 24 months. Other outcome variables analyzed were near visual acuity and contrast sensitivity. The C Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article. proportions of patients losing 3 or more or 6 or more lines of distance and near acuity and 0.3 or more or 0.6 or more log units of contrast sensitivity at each follow-up were also analyzed. Results: At all time points, mean distance visual acuity was better in the radiotherapy-treated group than in the control group, but the differences did not reach statistical significance. At 24 months, analysis of the proportions of patients with loss of 3 or more (moderate) (P=.08) or 6 or more (severe) (P = .29) lines of distance vision showed that fewer treated patients had severe losses, but there was no statistically significant difference between groups. For near visual acuity, although there was no evidence of treatment benefit at 12 and 24 months, a significant difference in favor of treatment was present at 6 months (P=.048). When analyzed by the proportions of patients losing 3 lines of contrast sensitivity, there was a significant difference in favor of treatment at 24 months (P=.02). No adverse retinal effects were observed during the study, but transient disturbance of the precorneal tear film was noted in treated patients. Conclusion: The results of the present trial do not sup- port the routine clinical use of external beam radiation therapy in subjects with subfoveal choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:1029-1038 HOROIDAL neovascularization (CNV) as a complication of age-related macular disease has a poor visual outcome, with 60% of affected patients becoming severely visually impaired within 3 years.1 Reports2-5 from randomized controlled clinical trials, starting in the 1980s, indicated that photocoagulation benefited the small proportion of patients found to have (REPRINTED) ARCH OPHTHALMOL / VOL 120, AUG 2002 1029 extrafoveal or juxtafoveal classic CNV. Unfortunately, because recurrence of new vessel growth occurred in most cases, treatment served only to delay visual loss in most.5,6 In patients who have occult CNV7 or a mixture of classic and occult disease, there is no evidence of benefit by argon laser therapy.8 One study9 implied that laser photocoagulation treatment confers benefit even when the neovascular complex is subfoveal. In this study, 24 months WWW.ARCHOPHTHALMOL.COM ©2002 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ on 10/15/2014 PATIENTS AND METHODS DESIGN AND INCLUSION AND EXCLUSION CRITERIA This trial was conducted in accord with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, 1996, for studies on human subjects. The SFRADS was undertaken in 3 ophthalmic units in major National Health Service hospitals located in Belfast, Northern Ireland, and in London and Southampton, England. The trial design was developed by the steering committee and approved by the local ethics committee at each center before commencement of the study. Patients with a presumptive diagnosis of subfoveal CNV due to ARMD were screened in special study clinics. A full medical history was obtained for each subject. This included current medications, history of hypertension, respiratory and cardiovascular status, prior major surgery, malignant disease, and smoking status. After giving informed consent, suitable patients were recruited into the study and were randomized to the treated (EBRT) or control (observation only) group. Patients in the treated group were scheduled to receive radiotherapy within 14 days of entry, and both groups were examined at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months after randomization, when standard efficacy and safety variables were recorded. The optometrists who undertook visual assessments were unaware of the treatment status of the patients; however, neither the treating physicians nor the patients were masked. Enrollment commenced November 1995, and was completed July 1998. Patients were required to be aged 60 years or older and have evidence of subfoveal CNV (some classic CNV or a vascularized pigment epithelial detachment) on a fundus fluorescein angiogram performed within 1 week of randomization. Visual acuity at baseline was required to be 20/200 or better in the study eye. Exclusion criteria were (1) inability to give informed consent; (2) angiographic evidence of late leakage of indeterminate origin only; (3) presence of blood under the geometric center of the fovea; (4) presence of additional ocular disease, including high myopia in excess of −6.0 diopter in any axis; (5) diabetes mellitus, uncontrolled hypertension, or any life-threatening disorder at the initial visit; (6) concurrent enrollment in any other ophthalmic clinical trial; and (7) prior radiotherapy to either eye. Patients who might benefit from foveal ablation according to the Macular Photocoagulation Study (MPS) criteria25 were made aware of this option and were invited to participate in the SFRADS only if they declined photocoagulation. MEASURES OF VISUAL FUNCTION All patients underwent assessment of visual function by a trained optometrist, using a protocol adapted from the MPS Manual of Procedures.26 All measurements were performed on each eye. Following refraction, best-corrected DVA was measured on the logMAR scale, using the backlit Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study charts. The line with the smallest letters in which at least 3 of the letters were correctly identified was entered as the line acuity for that eye. The number of letters read was also recorded to give a letter score for that eye. Best corrected near visual acuity (NVA) in each eye at 25 cm was obtained using the Bailey- (REPRINTED) ARCH OPHTHALMOL / VOL 120, AUG 2002 1030 Lovie near-reading chart. Contrast sensitivity was measured for each eye using the Pelli Robson chart, with the patient seated at the recommended distance of 1 m. Slitlamp biomicroscopy of anterior and posterior segments and intraocular pressure measurement were carried out on both eyes of every patient. High-dose radiotherapy is known to have adverse effects on the conjunctiva, lens, and retina. Detailed monitoring of these tissues was carried out at baseline and each subsequent visit. The conjunctiva was examined for vascular changes, such as microaneurysms and telangiectasia. The lacrimal system was evaluated as follows: The state of the precorneal tear film and the cornea were examined by slitlamp biomicroscopy. The tear film breakup time was measured and the Schirmer test was performed. Lens clarity was monitored using a clinical grading system and red-reflex anterior segment photography. The retina and its vasculature were monitored for radiation retinopathy by biomicroscopic examination, electrophysiological assessment, and scrutiny of fundus photographs and fluorescein angiograms. The presence of retinal vessel microaneurysms or hemorrhage remote to the CNV was recorded. ANGIOGRAPHY Most patients referred to the study clinic had been previously assessed angiographically by their referring physician. A routine angiogram was usually sufficient to assess eligibility. On entry into the study, if not already performed for eligibility purposes, a study angiogram was undertaken. The photographic protocol specified the taking of bilateral color stereopair and red-free photographs centered on the macula. During angiography, stereo-pair photographs of the macula of the study eye were taken throughout the transit phase. Stereo pairs of the study eye and the fellow eye were captured during the later phases of the angiographic procedure, defined as 2 to 5 minutes after injection. Angiograms were scrutinized by the principal investigators (U.C., P.M.H., A.C.B., and I.H.C.) at each center, who ascertained eligibility using a checklist of inclusion and exclusion criteria. The CNV was classified based on the fluorescein angiographic appearance of a lesion by the reading center based in Belfast. The size of the lesion (defined as any abnormal fluorescence, elevated blocked fluorescence, or contiguous blood) and the area of classic hyperfluorescence were measured in disc areas according to MPS criteria. Lesions were classified as wholly or predominantly classic (ⱖ50% of the lesion), minimally classic (1%49% of the lesion), occult (0%), or vascularized pigment epithelial detachment. Of the 203 baseline angiograms, 110 were read by a senior MPS-certified grader from The Scheie Eye Institute Photographic Reading Center, Philadelphia, Pa. Agreement between Belfast graders and the MPScertified grader was high, with a value of 0.89. Discordance was primarily because of differences in the grading of mixed lesions, with Belfast graders classifying more cases as minimally classic than the MPS grader. There was no disagreement between graders in lesions classified as either purely classic or purely occult. RANDOMIZATION Eligible subjects were counseled and informed consent was obtained. The randomization code was kept at the WWW.ARCHOPHTHALMOL.COM ©2002 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ on 10/15/2014 coordinating center (Belfast) and released by telephone on receipt of patient details. To ensure balance within each of the 3 centers, the randomization was blocked. Two hundred three patients were recruited from 477 screened, and the detailed flowchart depicting study participation is shown in Figure 1. RADIOTHERAPY TECHNIQUE Patients in the treatment arm were assessed in the radiotherapy unit in each center by the designated radiotherapist. All centers used a 6-mV photon beam from a linear accelerator, and the dosage of radiotherapy selected for this study was 12 Gy given as 6 equal fractions on consecutive working days. The treatment plan was based on a high-definition computed axial tomographic scan, taken with the patient’s head immobilized using a custom-made bexoid beam direction shell. Fine radiopaque tubing was placed on the beam direction shell marking the sagittal and coronal planes to establish reference points for the treatment port. The tomogram selected for treatment planning was one that clearly showed the lens, medial and lateral recti, and optic nerve of the ipsilateral eye in the same slice and included a clear view of the lens and optic nerve of the contralateral eye. The whole length of the optic nerve may be demonstrated in 1 slice when the chin is raised to bring the orbitomeatal line to an angle of 16° to the vertical. The patient was instructed to keep his or her eyes closed while the scan was performed. The treatment plan was constructed using a computer-based software program (Theraplan 500 series; Theratronics, Ottawa, Ontario) for 6-mV photons prescribed to the 90% isodose. In the generation of the treatment plan, care was taken to minimize exposure to the optic nerves of both eyes and the ipsilateral lens. The 90% isodose curve included the macula and optic disc, with less than 50% of the maximum dose falling on the posterior lens capsule. The eye was irradiated through a single lateral port measuring 3⫻3 cm. The beam was angled 10° posteriorly to avoid the lens of the contralateral eye. Cursor measurements were made from the surface reference marks on the beam direction shell to localize the lateral beam entry port. This port was marked on the beam direction shell using a treatment simulator. Before treatment, or following the first treatment session, a monitoring computed axial tomographic scan was performed to confirm the accuracy of beam placement. Eighty-eight percent of patients received radiotherapy within 3 weeks of randomization and the remainder within 4 weeks. OUTCOME MEASURES The primary outcome measure, change in DVA in the study eye, was chosen because of its traditionally accepted role as a marker for visual function. We also measured NVA and CS as a set of secondary outcomes. With respect to patient-centered outcomes, we collected information on self-reported visual functioning and health-related quality of life; these measures are reported elsewhere (M.R.S., P.M.H., A.C.B., I.H.C., and U.C., unpublished data, 2002). The null hypotheses of primary interest were that there was no difference in change in DVA between treated and control groups at 12 and 24 months. As this is a longitudinal (REPRINTED) ARCH OPHTHALMOL / VOL 120, AUG 2002 1031 study, we also routinely report outcome at 3 and 6 months and the group trajectories over time after randomization for each of the outcome measures. As a means of comparing the results with those of previous studies, we also analyzed the number of lines of acuity lost from baseline to the 12- and 24-month examinations in the 2 groups. Losses of 3 or more or 6 or more lines of DVA and NVA (which reflects a doubling or a quadrupling of the visual angle) were used as binary outcomes. Similarly, for CS, losses of 0.3 log units (2 triplets) or 0.6 log units (4 triplets) were used as binary outcomes. A decrease of 0.3 log units or 2 triplets on the Pelli Robson chart represents a halving of the contrast threshold from the baseline value. Therefore, these latter measures may be regarded formally as comprising a second set of secondary outcomes of interest. STATISTICAL METHODS Design The study was designed to be 95% confident in detecting a minimum mean difference in DVA of 2 lines on the logMAR scale between treated and control groups with 90% power. Initial power calculations were made using data from the pilot study,14 and the sample size was determined to be 240 observations (120 per arm). Revised calculations based on the generalized Laird-Ware model27 allowed a subsequent reduction in sample size to 200 without loss of power. The study was not powered to investigate NVA, CS, or the second set of secondary outcomes. Analysis Standard univariate methods (2 and t tests and parametric and nonparametric analyses of variance) were used to analyze the data. The 5% level of statistical significance was adopted throughout to construct tests of hypotheses and confidence intervals (CIs). In relation to the outcomes of DVA, NVA, and CS, longitudinal multiple linear regression modeling was used, which allowed us to adjust the treatment effect for factors measured at baseline and the trend over time. In longitudinal studies, repeated measurements made on each individual are correlated, and alternative models are required that allow for this correlation. Accordingly, we adopted a specially modified Laird-Ware model27 that allows for correlation between the repeated measures when the individual follow-up examinations are irregularly spaced in time.28 The effects of the following factors were considered in these analyses: (1) treatment indicator, (2) time trend after randomization, (3) treatment by time interaction, (4) baseline value of the outcome measure, (5) CNV composition (classic or predominantly classic vs other), (6) center, and (7) whether both eyes were affected. Scheduled follow-up examinations necessitate that information accruing over time is interval-censored and does not accurately reflect time to event. In the Kaplan-Meier– based presentations of the cumulative proportions of patients losing 3 or more or 6 or more lines of visual acuity, we used the scheduled, rather than the observed, visit times, and this is in accord with most previously published randomized clinical trials in this field.4-11 WWW.ARCHOPHTHALMOL.COM ©2002 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ on 10/15/2014 Screened (N = 477) Table 1. No. of Participants From Each Center* Did Not Meet Angiographic Criteria (n = 126) Did Not Meet Visual Acuity Criteria (n = 54) Refused Consent (n = 24) Age-Related Macular Degeneration Not Confirmed (n = 21) Systemic Disease (n = 20) Prior Laser Therapy (n = 16) Other Eye Disease (n = 13) Study Group Center Treatment Control Belfast Southampton London Total 42 (50.6) 23 (48.9) 34 (49.3) 99 (49.7) 41 (49.4) 24 (51.1) 35 (50.7) 100 (50.3) Total 83 47 69 199 (100) (100) (100) (100) *Data are given as number (percentage). Randomized (n = 203) Allocated to Treatment (n = 101) Received External Beam Radiation Therapy as Allocated (n = 101) Reallocated From Observation (n = 1) Protocol Violations (n = 3) (age <60 y = 1; Visual Acuity Worse Than 20/200 = 2) Allocated to Observation (n = 102) Inadvertently Received Radiotherapy (n = 1) (Analyzed as Treated) Other Protocol Violations (n = 1) (Visual Acuity Worse Than 20/200) Treatment (n = 99) Control (n = 100) Follow-up, mo 3 = 91 6 = 93 12 = 93 24 = 87 Complete Visual Outcome Data Were Obtained at Every Time Point Follow-up, mo 3 = 95 6 = 87 12 = 91 24 = 88 Complete Visual Outcome Data Were Obtained at Every Time Point tions) of 6-mV photons delivered as external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) to the macula of eyes with CNV resulted in benefit of maintained DVA in the treated group.22 More recently, 2 additional randomized controlled trials of EBRT vs sham irradiation demonstrated no visual benefit in subjects observed for up to 1 year.23,24 We commenced a prospective, longitudinal, multicenter, randomized controlled trial November 1995, to investigate the hypothesis that 12 Gy of EBRT would limit the loss of visual function in patients with ARMD in whom CNV involved the fovea. The acronym used to designate the Subfoveal Radiotherapy Study is SFRADS. Patients were observed for 24 months, and the visual outcomes are reported herein. RESULTS Figure 1. Flowchart depicting participation in the Subfoveal Radiotherapy Study. PATIENTS ANALYZED after enrollment, mean losses of 3.0 and 4.4 lines of distance visual acuity (DVA) were recorded in treated and control eyes, respectively. Greater benefit was seen with maintained contrast sensitivity (CS) and reading speed at the same time point. As central vision is substantially reduced immediately after foveal ablation, any benefit is therefore only detectable in the longer term. Because of the disappointing outcome with or without intervention in this common ophthalmic condition, several novel therapeutic approaches have been proposed for the treatment of subfoveal CNV during the past decade. Recent studies10,11 showed that photodynamic therapy with verteporfin reduces the risk of moderate and severe vision loss in patients with subfoveal CNV in agerelated macular degeneration (ARMD). This treatment exploits the property of verteporfin uptake by the endothelia of the CNV, and targeted activation of the dye, using an infrared laser, results in occlusion of the neovascular complex, with minimal or no initial damage to the adjacent retinal neuropile. The use of ionizing radiation to cause involution of the CNV is another possible therapeutic approach. Clinical studies have been undertaken, with some identifying a visual benefit,12-19 and others20,21 suggesting a lack of benefit and adverse outcome due to teletherapy. However, none of these studies incorporated a concurrently recruited control group with visual and angiographic baseline characteristics similar to those of the treated group. A small randomized controlled trial consisting of 74 patients showed that a total dose of 24 Gy (in 4 frac(REPRINTED) ARCH OPHTHALMOL / VOL 120, AUG 2002 1032 Two hundred three patients were randomized into this study, and the numbers from each center are shown in Table 1. Of the 203, 4 were subsequently found not to satisfy all study entry criteria. One patient was aged 56, and 3 patients had baseline DVAs of 1.1 logMAR or worse. Three of these 4 were allocated to the treatment group. These 4 patients were excluded from the analysis. One other patient was randomized to the control group but subsequently received treatment according to protocol. This patient was analyzed as if she had been allocated to the treatment group. The baseline angiograms of the study eyes were graded for CNV composition, and the lesions were classified as purely or predominantly classic (145 [72.9%]), minimally classic (45 [22.6%]), occult with no classic (3 [1.5%]), or fibrovascular pigment epithelial detachment (6 [3.0%]). Although the reading center classified the study eyes of 3 patients as having no classic CNV at baseline, these subjects were not excluded from the analysis, as this was not considered a protocol violation. This is because the criterion specifying the presence of at least some classic CNV is subjective, and arbitration may be used in the event of disagreements between reading center staff and investigators. The flow chart (Figure 1) shows the route to the final numbers of participants analyzed within the treatment and control groups. BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS Randomization achieved prior similarity between the treated and control groups (Table 2). Most patients in WWW.ARCHOPHTHALMOL.COM ©2002 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ on 10/15/2014 Table 2. Baseline Characteristics* Table 3. Estimated Treatment Benefit to Distance Visual Acuity (DVA)* Group Factors Treatment Control Categorical Sex Male 43 (43.4) 43 (43.0) Female 56 (56.6) 57 (57.0) Index Right 53 (53.5) 54 (54.0) Left 46 (46.5) 46 (46.0) Fellow eye Unaffected 38 (38.4) 51 (52.0) Affected 61 (61.6) 47 (48.0)† CNV morphologic structure Classic 49 (49.5) 55 (55.0) Predominantly classic 21 (21.2) 20 (20.0) Minimally classic 25 (25.3) 20 (20.0) Occult 2 (2.0) 1 (1.0) Vascularized pigment 2 (2.0) 4 (4.0) epithelial detachment Continuous‡ Age, y 75.31 (0.64) 75.23 (0.64) Duration of symptoms, wk 13.01 (1.05) 14.24 (1.01) Initial DVA 0.59 (0.02) 0.58 (0.02) Initial NVA 0.87 (0.03) 0.86 (0.04) Initial CS 1.13 (0.03) 1.08 (0.03) Total 86 (43.2) 113 (56.8) 107 (53.8) 92 (46.2) 89 (45.2) 108 (54.8) 104 (52.3) 41 (20.6) 45 (22.6) 3 (1.5) 6 (3.0) Follow-up, mo Benefit SE No. of Participants P Value 3 6 12 24 −0.051 −0.085 −0.060 −0.091 0.039 0.052 0.055 0.056 185 179 183 174 .19 .11 .28 .11 *Data are given as logMAR acuity. Multiply times 10 to obtain the number of lines of distance visual acuity. Benefit indicates the difference in group averages (treatment minus controls) in change in DVA from baseline. The number of participants varies according to the number of completed visits. Table 4. Lines of DVA Lost by 3, 6, 12, and 24 Months of Follow-up* Group Lines of DVA Lost 75.27 (0.45) 13.63 (0.73) 0.59 (0.02) 0.86 (0.02) 1.10 (0.02) *Data are given as number (percentage) unless otherwise indicated. CNV indicates choroidal neovascularization; DVA, distance visual acuity; NVA, near visual acuity; and CS, contrast sensitivity. †Two fellow eyes did not have acuity recorded. ‡Continuous data are given as mean (SE). the study (72.9%) had wholly or predominantly classic CNV. COMPLETENESS OF FOLLOW-UP During the study, 48 visits were missed, and the numbers of missed visits and withdrawals were similar among treatment groups and centers. By 3 mo ⱖ3† ⱖ6‡ By 6 mo ⱖ3§ ⱖ6㛳 By 12 mo ⱖ3¶ ⱖ6# By 24 mo ⱖ3** ⱖ6†† Treatment Control Total 24 (26.4) 5 (5.5) 31 (33.0) 9 (9.6) 55 (29.7) 14 (7.6) 38 (40.9) 18 (19.4) 43 (50.0) 20 (23.3) 81 (45.3) 38 (21.2) 53 (57.0) 26 (28.0) 52 (57.8) 37 (41.1) 105 (57.4) 63 (34.4) 61 (70.1) 37 (42.5) 71 (81.6) 44 (50.6) 132 (75.9) 81 (46.6) *Data are given as number (percentage) of participants. The number of participants varies according to the number of completed visits. DVA indicates distance visual acuity. †21 = 0.97, P = .34. ‡21 = 1.10, P = .29. §21 = 1.51, P = .22. 㛳21 = 0.41, P = .52. ¶21 = 0.01, P = .91. #21 = 3.51, P = .06. **21 = 3.13, P = .08. ††21 = 1.13, P = .29. VISUAL OUTCOMES the treatment and control groups ( Figure 2 and Distance Visual Acuity Table 3 shows that the primary null hypotheses could not be rejected at 12 and 24 months. Although the difference between the groups at 12 and 24 months favored treated patients, the magnitude of the difference, less than 1 line of DVA, was small and did not reach statistical significance. The findings were similar at 3 and 6 months. The longitudinal regression analysis was conducted by systematically removing redundant terms from the model, and this showed that the treatment indicator remained nonsignificant throughout. Analysis of the data on the basis of lines of acuity lost showed that a greater proportion of patients in the control group lost 3 or more or 6 or more lines at each follow-up visit, but the differences did not reach statistical significance (Table 4). These findings are corroborated by examination of the cumulative proportions of patients losing 3 or more or 6 or more lines of DVA in (REPRINTED) ARCH OPHTHALMOL / VOL 120, AUG 2002 1033 Figure 3). Near Visual Acuity At the primary follow-up visits, at 12 and 24 months, no statistically significant difference between the groups was detected. However, the difference between treated and control groups was statistically significant at 6 months (t test, P=.048) (Table 5), when the magnitude of the change was −0.102, which is equal to 1 line of NVA (95% CI, 0.001-0.203). As noted previously with DVA, the direction of the mean change from baseline in NVA always favored treated patients during the study, and this is shown in Figure 4. When the data were analyzed by longitudinal regression, no treatment benefit was found. In only one regression analysis did the treatment effect () approach statistical significance (=−0.07, SE=0.04, t=−1.94, P value is between .05 and ⬍.10), when adjusting for time and baseline NVA. WWW.ARCHOPHTHALMOL.COM ©2002 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ on 10/15/2014 1.0 Table 5. Estimated Treatment Benefit to Near Visual Acuity (NVA)* Follow-up, mo Benefit SE No. of Participants P Value 3 6 12 24 −0.066 −0.102 −0.061 −0.076 0.042 0.051 0.052 0.057 186 179 181 172 .12 .048† .25 .19 Cumulative Proportion 0.8 0.6 0.4 Group Treatment Treatment-Censored Control Control-Censored 0.2 0 0.0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 *Data are given as logMAR near acuity. Benefit indicates the difference between group averages (treatment minus controls) in change in NVA from baseline. The number of participants varies according to the number of completed visits. †P⬍.03 in nonparametric testing. 1.5 2.5 Time, y 1.0 Cumulative Proportion 0.8 Change in NVA (LogMAR) 1.0 Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier–based graph of proportions of eyes losing 3 logMAR lines of distance acuity. At all time points, fewer eyes assigned to treatment lost 3 lines of acuity compared with the control group. No statistically significant differences were seen at any of the time points. 0.5 0.0 – 0.5 –1.0 0.6 –1.5 0.0 0.4 Group Trend for Treatment Group Treatment Group 0.5 1.5 1.0 Trend for Control Group Control Group 2.0 2.5 3.0 Time, y Group Treatment Treatment-Censored Control Control-Censored 0.2 0 0.0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 Figure 4. Change in near visual acuity (NVA) over time. Nonparametric trend lines fitted to the data show separation between treatment and control groups, which is maximum in the first 6 months of the study. Although treatment and control groups lost acuity during the study, the loss is less in the former. 2.5 Time, y Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier–based graph of proportions of eyes having severe vision loss (loss of 6 logMAR lines of distance acuity). Maximum divergence between treatment and control groups is seen from 12 months onward, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (P=.12). When the proportions of patients losing 3 or more or 6 or more lines of NVA were examined, statistically significant differences were detected at 3 and 6 months but not at 12 or 24 months (Table 6). Kaplan-Meier– based graphs show the cumulative proportions of patients losing 3 or more or 6 or more lines of NVA over time (Figure 5 and Figure 6). Contrast Sensitivity Table 7 shows that the primary null hypotheses could not be rejected at 12 and 24 months. As before, mean changes in CS from baseline favored treated (REPRINTED) ARCH OPHTHALMOL / VOL 120, AUG 2002 1034 patients throughout the study but did not reach statistical significance. The longitudinal regression analysis revealed a marginally significant treatment effect when time and baseline CS were entered into the model: ( = 0.09, SE = 0.04, t = 2.0, P value is between .02 and ⬍.05). At all time points, the proportion of patients losing 0.3 or more or 0.6 or more log units of CS was lower in the treatment group than in controls (Table 8). At 12 months, the difference was not significant; 34 patients (37.4%) had lost 0.3 or more log units of CS in the treatment group, compared with 45 patients (49.5%) in the control group (difference, 12.1%; 95% CI, −1.9% to 26.1%). At 24 months, there was evidence of a significant difference in the loss of 0.3 log units of CS in favor of treatment (treated, 43.5%, vs controls, 60.9%; difference, 17.4%; 95% CI, 3.4%-31.4%) (Figure 7 and Figure 8). WWW.ARCHOPHTHALMOL.COM ©2002 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ on 10/15/2014 Group Lines of NVA Lost By 3 mo ⱖ3† ⱖ6‡ By 6 mo ⱖ3§ ⱖ6㛳 By 12 mo ⱖ3¶ ⱖ6# By 24 mo ⱖ3** ⱖ6†† Treatment Control Total 19 (20.9) 5 (5.5) 35 (36.8) 15 (15.8) 54 (29.0) 20 (10.8) 43 (46.2) 12 (12.9) 54 (62.8) 21 (24.4) 97 (54.2) 33 (18.4) 53 (57.0) 22 (23.7) 55 (62.5) 28 (31.8) 108 (59.7) 50 (27.6) 58 (66.7) 27 (31.0) 61 (71.8) 36 (42.4) 119 (69.2) 63 (36.6) Cumulative Proportion 0.5 Table 6. Lines of NVA Lost by 3, 6, 12, and 24 Months of Follow-up* 0.4 0.3 Group Treatment Treatment-Censored Control Control-Censored 0.2 0.1 0.0 0.0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 Time, y Figure 6. Kaplan-Meier–based graph of proportions of eyes losing 6 or more lines of near acuity. At all time points, fewer eyes assigned to treatment lost 6 or more lines of acuity compared with the control group, although the difference did not reach significance (P = .17). Table 7. Estimated Treatment Benefit to Contrast Sensitivity (CS)* *Data are given as number (percentage) of participants. The number of participants varies according to the number of completed visits. NVA indicates near visual acuity. †21 = 5.75, P = 0.02. ‡21 = 5.13, P = 0.02. §21 = 4.93, P = 0.03. 㛳21 = 3.94, P = 0.05. ¶21 = 0.57, P = 0.45. #21 = 1.51, P = .22. **21 = 0.52, P = .47. ††21 = 2.37, P = .12. Follow-up, mo Benefit SE No. of Participants P Value 3 6 12 24 +0.082 +0.056 +0.102 +0.052 0.046 0.062 0.065 0.067 184 178 182 172 .08† .36 .12‡ .44 *Data are given as log contrast threshold. Benefit indicates the difference between group averages (treatment minus controls) in change in CS from baseline. The number of participants varies according to the number of completed visits. †Nonsignificant on nonparametric testing (P = .10). ‡P=.06 in nonparametric testing. 1.0 Cumulative Proportion 0.8 0.6 0.4 Group Treatment Treatment-Censored Control Control-Censored 0.2 0.0 0.0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 Time, y Figure 5. Kaplan-Meier–based graph of proportions of eyes losing 3 or more lines of near acuity. Maximum separation between groups is seen between 3 and 6 months. This difference reached significance (P=.048). SAFETY OUTCOMES The analysis of the angiographic outcomes will be the subject of a detailed further report. No patients were found to develop features of radiation retinopathy in the 24 months after trial entry. As we did not carry out indocyanine green angiography, we could not rule out radiation-induced choroidopathy. Treatment and control groups had similar tear film breakup times at baseline (mean, 11.6 and 11.3 (REPRINTED) ARCH OPHTHALMOL / VOL 120, AUG 2002 1035 seconds, respectively). At 3 months, this decreased in the treatment group by a mean (SD) of 1.7 (0.8) seconds, compared with an increase of 0.6 (0.8) seconds in the control group (P = .03). A similar finding was noted at 6 months (P =.04) but not at subsequent time points. Statistically significant differences in Schirmer test results were also noted between treatment and control groups at 6 and 12 months. At baseline, mean Schirmer test values were 11.84 and 12.74 mm, respectively, but at 6 months, the mean (SD) in the treatment group had decreased by 0.83 (0.94) mm, whereas in the control group the mean increased by 1.98 (0.94) mm (P = .04). By 12 months, the mean in the treated group had decreased by 2.27 mm from baseline, compared with an increase in the control group of 0.92 mm (P =.02). COMMENT The present study and most other clinical trials in ophthalmology have used DVA as a principal outcome measure.1-10 This measure of vision is based on the ability of the eye to resolve targets at a distance, and it is generally accepted that threshold visual acuity, when measured using the logMAR chart to standardized protocols, provides a useful yardstick for monitoring outcome for research purposes. However, the validity of using DVA alone has been questioned in assessing the benefits of treatment for ocular disorders, including ARMD.29-32 For this reason, 2 addiWWW.ARCHOPHTHALMOL.COM ©2002 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ on 10/15/2014 Group Log Units CS Lost By 3 mo ⱖ0.3† ⱖ0.6‡ By 6 mo ⱖ0.3§ ⱖ0.6㛳 By 12 mo ⱖ0.3¶ ⱖ0.6# By 24 mo ⱖ0.3** ⱖ0.6†† Treatment Control Total 21 (23.6) 6 (6.7) 34 (35.8) 15 (15.8) 55 (29.9) 21 (11.4) 30 (33.0) 15 (16.5) 36 (41.4) 19 (21.8) 66 (37.1) 34 (19.1) 34 (37.4) 18 (19.8) 45 (49.5) 27 (29.7) 79 (43.4) 45 (24.7) 37 (43.5) 24 (28.2) 53 (60.9) 26 (29.9) 90 (52.3) 50 (29.1) *Data are given as number (percentage) of participants. The number of participants varies according to the number of completed visits. CS indicates contrast sensitivity. †21 = 3.26, P = .07. ‡21 = 3.72, P = .05. §21 = 1.35, P = .24. 㛳21 = 0.83, P = .35. ¶21 = 2.71, P = .10. #21 = 2.39, P = .12. **21 = 5.21, P = .02. ††21 = 0.06, P = .81. 1.0 Cumulative Proportion 0.8 0.6 0.4 Group Treatment Treatment-Censored Control Control-Censored 0.2 0.0 0.0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 Time, y Figure 7. Kaplan-Meier–based graph of proportions of eyes losing 0.3 or more log units of contrast sensitivity. At all time points, proportionately fewer eyes assigned to treatment lost 0.3 or more log units of contrast compared with the control group. The differences between treatment and control groups was highly significant (P =.005). tional variables of visual function, NVA and CS, are also presented in this study. The study was designed to detect an average difference of 2 logMAR lines of DVA with 90% power and 95% confidence. The magnitude of the detectable difference was based on the results of a pilot study,12,14 which suggested a potential 2-line benefit likely to have an effect on visual function in the study population. (REPRINTED) ARCH OPHTHALMOL / VOL 120, AUG 2002 1036 Cumulative Proportion 0.5 Table 8. Log Units of CS Lost by 3, 6, 12, and 24 Months of Follow-up* 0.4 0.3 0.2 Group Treatment TreatmentCensored 0.1 0.0 0.0 0.5 1.0 1.5 Control ControlCensored 2.0 2.5 Time, y Figure 8. Kaplan-Meier–based graph of proportions of eyes losing 0.6 or more log units of contrast sensitivity. Proportionately fewer eyes assigned to treatment lost 0.6 or more log units of contrast compared with the control group, but the difference was not statistically significant (P = .11). In the SFRADS, DVA was not statistically significantly different between the study groups at 12 or 24 months, when we believe a benefit would have been clinically useful. During the study, visual outcome was better on average in treated patients, but the differences observed were smaller than those considered likely to be clinically relevant, and most were not statistically significant. When considering mean differences between the groups, the only single measure of outcome that was significantly different was mean NVA at 6 months, and the magnitude of this difference was 1 logMAR line, the 95% CI being consistent with an effect size ranging from just above zero to 2 logMAR lines. The analysis of dichotomous variables in relation to NVA suggests the presence of an early therapeutic effect (not sustained beyond 6 months). This finding is more persuasive given that these differences were detected despite the fact that the SFRADS was not powered to investigate these aspects of visual outcome. However, the significant findings in relation to CS at 3 and 24 months are more difficult to explain and accordingly are less convincing. Therefore, when all outcome measures were considered, the data suggest that visual outcome was better in treated patients. That the data imply, but do not establish beyond doubt, that a therapeutic effect exists is consistent with the mixed conclusions of other studies22-24 using low-dose radiotherapy. Bergink et al22 concluded that 24 Gy of radiation given as 4 fractions of 6 Gy was effective in reducing moderate and severe visual loss in eyes with CNV in ARMD. However, more recent studies23,24 did not find any evidence of benefit from EBRT. The absence of a therapeutic effect in the latter studies is unlikely to be related to variation in dosage, as similar dosages were used (16 Gy23 and 14 Gy24 vs 12 Gy in the SFRADS). However, there are other factors that could account for the variation in outcome. In one study,23 most subjects (55.6%) had purely occult CNV, and in the other,24 fewer than 14% of subjects were graded at baseline as having classic CNV only. In comparison, most subjects in the SFRADS (72.9%) belonged to the wholly classic or predominantly classic subgroups. Furthermore, the studies with negative findings were based on 12 months of data alone. Other small randomized controlled studies33,34 WWW.ARCHOPHTHALMOL.COM ©2002 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ on 10/15/2014 have used sources of radiotherapy that are more capable of precisely delineating the target area, including proton beam and plaque radiotherapy. Although the data from these studies are encouraging, the high dosages of radiation to the choroidal vasculature may result in greater damage to the choroid and retinal pigment epithelium, with the prospect of a worse visual outcome than that associated with the natural history. In this regard, several reports20,21,35 suggest that EBRT to CNV may cause abnormal vascular proliferations in the retinal and choroidal circulations. The results of the present study indicate that radiotherapy to a subfoveal CNV given as 6 fractions to a total dosage of 12 Gy is not inimical and does not result in a worse visual outcome compared with the natural history. To our knowledge, none of the controlled trials thus far have reported radiation retinopathy or optic neuropathy, 22-24 and similarly we found no serious adverse effects, although some temporary abnormality of tear film was recorded. Also, the value of the small differences noted in acuity and contrast between treatment and control groups may not translate into improvements in visual functioning.32 The magnitude of benefit detected indicates that EBRT will not resolve the problem of blindness from age-related macular disease. Whether the magnitude of the detected benefit warrants the use of this treatment is questionable. Most subjects enrolled in the SFRADS had wholly or predominantly classic CNV and thus fall into the category of patients who would benefit from photodynamic therapy with verteporfin. 10,11 With photodynamic therapy, the need for successive treatments and the accompanying investigations have important implications for the patient. Also, there are health, economic, and cost-benefit issues to be considered when comparing treatments. 36 However, the smaller proportion (28%) of eyes losing 3 lines of acuity in a predominantly classic subgroup treated with photodynamic therapy10,11 is considerably better than that achieved by EBRT in this study (58%). It is therefore our opinion that the present study has not identified a specific clinical role for 12 Gy of photon radiotherapy given as a series of 6 fractions in the management of CNV in ARMD. Submitted for publication July 12, 2001; final revision received April 17, 2002; accepted April 24, 2002. From the Departments of Ophthalmology and Visual Science (Drs Hart and Chakravarthy) and Epidemiology (Dr Stevenson), Queen’s University of Belfast and Northern Ireland Radiotherapy Centre, Belvoir Park Hospital (Dr Houston), Belfast, Northern Ireland; School of Public Policy, Economics and Law, University of Ulster, Antrim, Northern Ireland (Dr McCulloch); and Centre for Medical Statistics, Keele University, Keele (Dr Mackenzie); Eye Unit, Southampton University Hospitals (Dr Chisholm) and Wessex Radiotherapy Centre, Royal South Hants Hospital, Southampton (Dr Hall), England; and Institute of Ophthalmology, University College (Dr Bird), Moorfields Eye Hospital (Dr Owens), and Department of Radiotherapy and Oncology, St Bartholomew’s Hospital (Dr Plowman), London, England. (REPRINTED) ARCH OPHTHALMOL / VOL 120, AUG 2002 1037 This study was supported by strategic project grant G9404235 from the Medical Research Council of the United Kingdom, London, International Standardized Random Control Trial Number (ISRCTN 84737434). The SFRADS group members thank the following: Judy Alexander, The Scheie Eye Institute; John Reeves, PhD, GD Searle, Inc, Chicago, Ill; M. Broadbery, MSc, and M. McClure, MSc, Royal Victoria Hospital, P. McEvoy, G. McGoldrick, and Kay Andrews, Queen’s University, and M. Burns, Green Park Hospitals Trust, Belfast; K. Grigg and A. Brannon, Moorfields Eye Hospital, London; and B. Ashleigh, K. Parrish, Sheila Davis, and Sheila Bryant, Southampton University Hospitals Trust, Southampton. Corresponding author and reprints: Usha Chakravarthy, FRCOphth, PhD, Department of Ophthalmology and Vision Science, The Royal Victoria Hospital, Queen’s University of Belfast, Grosvenor Road, Belfast BT12 6BA, Northern Ireland (e-mail: g.mcgoldrick@qub.ac.uk). REFERENCES 1. Macular Photocoagulation Study Group. Argon laser photocoagulation for senile macular degeneration: results of a randomized clinical trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982;100:912-918. 2. Macular Photocoagulation Study Group. Argon laser photocoagulation for idiopathic neovascularization: results of a randomized clinical trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 1983;101:1358-1361. 3. Macular Photocoagulation Study Group. Recurrent choroidal neovascularization after argon laser photocoagulation for neovascular maculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1986;104:503-512. 4. Macular Photocoagulation Study Group. Argon laser photocoagulation for neovascular maculopathy: three-year results from randomized clinical trials. Arch Ophthalmol. 1986;104:694-701. 5. Macular Photocoagulation Study Group. Laser photocoagulation for juxtafoveal choroidal neovascularization: five-year results from randomized clinical trials. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994;112:500-509. 6. Macular Photocoagulation Study Group. Argon laser photocoagulation for neovascular maculopathy: five-year results from randomized clinical trials. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109:1109-1114. 7. Macular Photocoagulation Study Group. Subfoveal neovascular lesions in agerelated macular degeneration: guidelines for evaluation and treatment in the Macular Photocoagulation Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109:1242-1257. 8. Macular Photocoagulation Study Group. Occult choroidal neovascularization: influence on visual outcome in patients with age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114:400-412. 9. Macular Photocoagulation Study Group. Laser photocoagulation of subfoveal neovascular lesions in age-related macular degeneration: results of a randomized clinical trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109:1220-1231. 10. Treatment of Age-Related Macular Degeneration With Photodynamic Therapy (TAP) Study Group. Photodynamic therapy of subfoveal choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration with verteporfin: one-year results of 2 randomized clinical trials: TAP report 1. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:13291345. 11. Bressler NB, for the Treatment of Age-Related Macular Degeneration With Photodynamic Therapy (TAP) Study Group. Photodynamic therapy of subfoveal choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration with verteporfin: two-year results of 2 randomized clinical trials: TAP report 2. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:198-207. 12. Chakravarthy U, Houston RF, Archer DB. Treatment of age-related subfoveal neovascular membranes by teletherapy: a pilot study. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993;77: 265-273. 13. Bergink GJ, Deutman AF, van den Broek JE, van Daal WA, van der Maazen RM. Radiation therapy for age-related subfoveal choroidal neovascular membranes: a pilot study. Doc Ophthalmol. 1995,90:67-74. 14. Hart PM, Chakravarthy U, MacKenzie G, Archer DB, Houston RF. Teletherapy for subfoveal choroidal neovascularisation of age-related macular degeneration: results of followup in a non-randomised study. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996;80:10461050. 15. Berson A, Finger PT, Sherr DL, Emery R, Alfieri A, Bosworth JL. Radiotherapy WWW.ARCHOPHTHALMOL.COM ©2002 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ on 10/15/2014 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. for age-related macular degeneration: preliminary results of a potentially new treatment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;36:861-865. Freire J, Longton WA, Miyamoto CT, et al. External radiotherapy in macular degeneration: technique and preliminary subjective response. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;36:857-860. Postgens H, Bodanowitz S, Kroll P. Low-dose radiation therapy for age-related macular degeneration. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1997;235:656-661. Brady LW, Freire JE, Longton WA, et al. Radiation therapy for macular degeneration: technical considerations and preliminary results. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;39:945-948. Yonemoto LT, Slater JD, Friedrichsen EJ, et al. Phase I/II study of proton beam irradiation for the treatment of subfoveal choroidal neovascularization in agerelated macular degeneration: treatment techniques and preliminary results. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;36:867-871. Spaide RF, Guyer DR, McCormick B, et al. External beam radiation therapy for choroidal neovascularization. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:24-30. Stalmans P, Leys A, Van Limbergen E. External beam radiotherapy (20 Gy, 2 Gy fractions) fails to control the growth of choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration: a review of 111 cases. Retina. 1997;17:481492. Bergink GJ, Hoyng CB, van der Maazen RWM, Vingerling JR, van Daal WA, Deutman AF. A randomized controlled clinical trial on the efficacy of radiation therapy in the control of subfoveal choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration: radiation versus observation. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1998;236:321-325. Radiation Therapy for Age-Related Macular Degeneration Study Group. A prospective, randomized double-masked trial on radiation therapy for age-related macular degeneration (RAD Study). Ophthalmology. 1999;106:2239-2247. Marcus DM, Sheils W, Johnson MH, et al. External beam irradiation of subfoveal choroidal neovascularization complicating age-related macular degeneration: one-year results of a prospective, double-masked, randomized clinical trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:171-180. Macular Photocoagulation Study Group. Visual outcome after laser photocoagu- 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. 32. 33. 34. 35. 36. lation for subfoveal choroidal neovascularization secondary to age-related macular degeneration: the influence of initial lesion size and initial visual acuity. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994;112:480-488. Macular Photocoagulation Study Group. MPS Manual of Procedures. Springfield, Va: National Technical Information Service; January 1991. Accession No. PB91-159376. Laird NM, Ware JH. Random-effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics. 1982;38:963-974. Reeves JAF, MacKenzie G. A bivariate regression model with serial correlation. J R Stat Soc Ser D. 1998;47:607-615. Elliott DB, Hurst MA, Weatherill J. Comparing clinical tests of visual function in cataract with the patient’s perceived visual disability. Eye. 1990;4:712717. Schein OD, Steinberg EP, Cassard SD, Tielsch JM, Javitt JC, Sommer A. Predictors of outcome in patients who underwent cataract surgery. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:817-823. Steinberg EP, Tielsch JM, Schein OD, et al. The VF14: an index of functional impairment in patients with cataracts. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994;112:630-638. McClure ME, Hart PM, Jackson AJ, Stevenson MR, Chakravarthy U. Macular degeneration: do conventional measurements of impaired visual function equate with visual disability? Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:244-250. Briggs MC, Natha A, Kacperek A, et al. Precision low-dose proton beam radiotherapy of subfoveal choroidal neovascularisation in age-related macular degeneration: 12-month results of a randomised controlled study [abstract]. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:s127. Immonen IJ, Jaakola A, Tommila P, et al. Strontium plaque radiotherapy for exudative age-related macular degeneration [abstract]. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:s127. Haas A, Prettenhoffer U, Stur M. Morphologic characteristics of disciform scarring after radiation treatment for age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:1358-1363. Laupacis A, Sackett DL, Roberts RS. An assessment of clinically useful measures of the consequences of treatment. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:1728-1733. Notice to Authors: Submission of Manuscripts Selected manuscripts submitted to the Archives of Ophthalmology will be submitted for electronic peer review. Please enclose a diskette with your submission containing the following information: File name Make of computer Model number Operating system Word processing program and version number (REPRINTED) ARCH OPHTHALMOL / VOL 120, AUG 2002 1038 WWW.ARCHOPHTHALMOL.COM ©2002 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ on 10/15/2014

© Copyright 2025