OPINION A Brazil Sticks With Statism

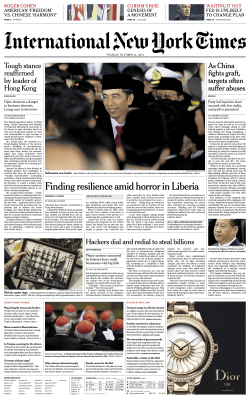

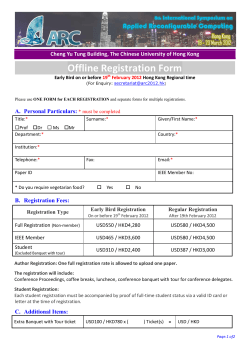

P2JW300000-0-A01700-1--------XA CMYK Composite CL,CN,CX,DL,DM,DX,EE,EU,FL,HO,KC,MW,NC,NE,NY,PH,PN,RM,SA,SC,SL,SW,TU,WB,WE BG,BM,BP,CC,CH,CK,CP,CT,DN,DR,FW,HL,HW,KS,LA,LG,LK,MI,ML,NM,PA,PI,PV,TD,TS,UT,WO THE WALL STREET JOURNAL. Monday, October 27, 2014 | A17 OPINION Brazil Sticks With Statism São Paulo n economic recession, inflation running at 6.7% and revelations of an audacious skimming scheme at the stateowned oil company Petrobras were not enough to deny Brazilian Workers’ Party (PT) President Dilma Rousseff re-election to a second term on Sunday. With 99% of the vote counted, the incumbent led with 51.56% of the vote against challenger Aécio Neves, of the Social Democratic Party of Brazil, with 48.44%. Ms. Rousseff ran as the antimarket, welfare-state canwhich AMERICAS didate, may be why she By Mary fared far better Anastasia in the poor, deO’Grady pendent north than she did in the prosperous agricultural heartland and here in Brazil’s largest city, where the economy relies heavily on services and value-added manufacturing. Like the U.S., Brazil has its upper-class, urban voters who feel virtuous backing state intervention in other peoples’ lives and supporting Cuba’s military dictatorship. But there is also an aspirational Brazil—which is made up of risk-taking entrepreneurs, globally competitive farmers and a rising middle class that hungers for greater engagement with the world. These Brazilians badly want the change Mr. Neves represented. They made Sunday’s contest the closest in Brazilian history. Like the proverbial dog that caught the car, Ms. Rousseff now has to figure out what to do with her next four years. She may believe she can further the consolidation of PT power—her highest goal—if she sticks to the policy O EPA A Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff after voting in Porto Alegre, Oct. 26. mix she has been using thus far, no matter the cost to the economy. Alternatively, she could make pragmatic economic adjustments with the goal of restoring confidence and growth. The latter is certainly possible. But it is unlikely because the party militants, who have fattened up during PT rule, want more power, not less. She may utter some conciliatory statements and in the short run take some small steps that favor liberty, just as her PT mentor, former President Lula da Silva (2003-10), did when he first took office in order to calm markets that were plummeting out of fear. But Lula soon reverted to form. Odds are that Ms. Rousseff will do the same, making Brazil’s legendary reputation for mediocrity safe for another four years. Only if a criminal investigation proves that Ms. Rousseff and Lula knew about the graft at Petrobras are things likely to go differently. The great irony of the campaign is that while Ms. Rousseff and Lula claimed the credit for Brazil’s turn-of-the-century revival, they both opposed the reforms of the 1990s. The privatization of state companies, the limited opening to foreign competition, and the 1994 “Brazilian real” currency plan to defeat hyperinflation all stimulated development and made more generous welfare programs, the trademark of the PT, possible. But the PT never followed through on those reforms and the “Brazilian miracle” died in the crib. At best the country runs in the middle of the emerging-market pack. More often it brings up the rear. Neither Lula nor Ms. Rousseff seem to care about development. According to Goldman Sachs, from 2004-13 government spending grew at almost 8% a year, in real terms, which was more than twice the rate of GDP growth. Inflation is now 7% year-over-year on prices for goods and services not regulated by price controls and 8.6% for services alone. Inflationary expectations are rising. Ms. Rousseff thought she could fix the problem by capping BOOKSHELF | By Martin Rubin the price of gasoline, which is supplied by Petrobras, and of ethanol, which is made by local sugar mills and used to make flex-fuel. But since production costs are not capped, Petrobras and the sugar mills are sustaining large losses. Some sugar mills are already bankrupt and others that I talked to said they won’t survive if the policy continues. The PT boasts about helping the poor with welfare but what it gives with one hand it takes— and more—with the other. Rising protectionism, steep payroll and consumption taxes, lousy infrastructure and heavy labor regulation are hidden costs that make all Brazilians worse off. More worrying is the damage the PT might do to institutions and the rule of law over another 48 months. Civil society here jealously guards civil liberties and pluralism. But as one astute businessman told me, “We are noticing, bit by bit, a trend toward copying Argentina, Bolivia and Ecuador. The tendency is to reduce democracy.” One example is Ms. Rousseff’s May decree empowering “popular councils,” which would move the country away from representative democracy à la Venezuela. Congress has so far refused to approve the measure but if the usual vote-buying goes on, that may change. This is creepy for anyone who has read history. As the 18thcentury political philosopher David Hume observed, “It is seldom that liberty of any kind is lost all at once.” Today Mrs. Rousseff is a politician who won an election. But Brazilians may someday learn that the oneparty state and indefinite rule are the real long-term projects of the PT. Write to O’Grady@wsj.com Beijing’s Hong Kong Disinformation fficials in Beijing claim they’re doing more for democracy in Hong Kong than Britain ever did in colonial days. “In 150 years, the country that now poses as an exemplar of democracy gave our Hong Kong compatriots not one single day of it,” declares an editorial in the Communist Party organ People’s Daily. It’s pure disinforation. INFORMATION m Starting AGE with the By L. Gordon era of Mao Crovitz Zedong, Chinese officials have fought against self-governance for Hong Kong, even threatening to invade if London extended democratic freedoms to the people of Hong Kong. Beijing’s resistance underscores the significance of the deal it negotiated with Britain in the 1980s pledging democracy for Hong Kong after the handover in 1997. Reneging on this commitment led hundreds of thousands of demonstrators to take to Hong Kong’s streets. According to recently declassified British records, Beijing warned London against democracy in Hong Kong soon after the communists took power on the mainland in 1949. In 1958 Premier Zhou Enlai opposed “a plot or conspiracy to make Hong Kong a self-governing dominion like Singapore.” He warned that “China would regard any move toward dominion status as a very unfriendly act. China wished the present colonial status of Hong Kong to continue with no change whatever.” In 1960 Chinese officials went further: “We shall not hesitate to take positive action to have Hong Kong, Kowloon and the New Territories liberated” if Britain permitted “self-government.” Margaret Thatcher was taken aback when she encountered fierce opposition from Deng Xiaoping during the handover negotiations. According to the minutes of a key 1982 meeting, made public last year, Thatcher told the Chinese leader that “her duty, which she felt deeply, was to reach a result acceptable to the people of Hong Kong.” She reminded him that even with limited democracy, Hong Kong already had “a political system which was very different from that of China.” Deng responded by warning Britain not to make any changes that would raise expectations for democracy. He warned that “if there were very large disturbances in the next 15 years, the Chinese government would be forced to reconsider the time and formula” for the handover. This is the backdrop for the promise Britain managed to extract in the 1984 Joint Declaration, which pledged “one country, two systems,” and in Hong Kong’s post-handover Basic Law ensuring “universal suffrage.” It also helps explain why Beijing denounced the last British governor, Chris Patten, as a “serpent” and a “prostitute for 1,000 years” for his modest democratic reforms. This year’s Umbrella Movement protests were provoked by China’s August announcement that in 2017 it will continue its current practice of permitting only Beijing loyalists to run for chief executive. Declassified records show China always opposed democracy, even when Hong Kong was a colony. Lawyers at the British Institute of International and Comparative Law this month published a detailed analysis of the treaties and laws relating to Hong Kong democracy. They concluded that Britain, as cosignatory to the Joint Declaration, has “clear standing” to object to violations. They show China agreed that the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights applies in Hong Kong. That “means both the right to be elected as well as the right to vote,” the United Nations Human Rights Committee declared last week. The British lawyers also noted the Basic Law promises “orderly progress” toward open elections. The risks of delay, they write, include “civil disorder in Hong Kong, loss of confidence among Hong Kong people in the system of governance, and loss of international confidence in the commercial and investment environment in Hong Kong.” Hong Kong’s Beijing-selected chief executive, C.Y. Leung, gave interviews last week opposing the right to vote as well as the right to run. “If it’s entirely a numbers game and numeric representation, then obviously you’d be talking to the half of the people in Hong Kong who earn less than [US]$1,800 a month,” he said. “Then you would end up with that kind of politics and policies.” Contrary to Mr. Leung’s remark, most Hong Kong people are proud of their free markets, economic mobility and low, flat income tax, which exempts most workers. In a free election, Hong Kong people would select candidates who pledge to protect Hong Kong’s independent judiciary and free press, restore its apolitical civil service and end favoritism for Beijing-friendly companies. Chinese officials fear that democracy in Hong Kong could encourage mainlanders to demand more freedoms for themselves. They oppose self-governance in Hong Kong for the same reason they always have: They know their repressive control could not survive a democratic vote—in Hong Kong or anywhere else in China. The Other Senate Nuclear Option The midterms might mean finally ending Harry Reid’s blockade of Yucca Mountain. the one-tenth of a cent per kilowatt-hour fee earlier this year, in response to a court order. Mr. Reid has unleashed his particular brand of heavy-handed politics to get his way on Yucca Mountain. As majority leader, he applied pressure on President Obama’s appointees at the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to secure commissioners who advanced his agenda. The NRC chairman who pulled the plug on Yucca Mountain was Gregory Jaczko, a former Senate aide to Mr. Reid. Just over a year after the administration scuttled the project in early 2010, the Government Accountability Office issued a report saying the Yucca Mountain Composite M uch is at stake as Americans vote on Nov. 4. While different races have different issues, the nuclearenergy world is watching to see which party will control the Senate. If Majority Leader Harry Reid becomes minority leader, he would likely no longer be able to sustain opposition to Yucca Mountain, the Energy Department’s chosen nuclear repository. On Oct. 16 the Nuclear Regulatory Commission issued its Yucca Mountain Safety Evaluation Report 3, stating that the facility meets the government’s long-term regulatory and safety requirements as a nuclear-waste repository, including the benchmark of remaining safe for a million years. The report is a culmination of decades of scientific and technical studies showing the underground facility in south-central Nevada to be safe and secure for storing spent fuel and other nuclear waste. Yet after nearly 30 years of study, at a cost of over $15 billion, Yucca Mountain is stuck in political gridlock. The idea of a national usednuclear-fuel repository was conceived in 1987 in an amendment to the 1982 Waste Policy Act, and Yucca Mountain was approved by Congress in 2002. In 2011, however, the Obama administration yanked the project’s funding. The president had plenty of help. Nevada Sen. Reid has made it his business to personally kill Yucca Mountain. This was despite the fact that ratepayers across the U.S. who use nuclear energy had already contributed $31 billion to the project—until Energy Secretary Ernie Moniz suspended shutdown was not only strictly political, but would also set back used-fuel storage efforts by two decades. As the New York Times reported at the time, “The Obama administration did not provide a technical or scientific basis for shutting down the site and failed to plan or identify risks associated with its hasty closure.” The Tennessee Valley Authority—which operates two nuclear plants in Tennessee and one in Alabama—has a deep commitment to producing safe, reliable and affordable nuclear energy for its customers. Over the last four decades, ratepayers in the Tennessee Valley who rely on the TVA and local power-supply companies paid about $53 million a year to the Energy Department to fund a used nuclear-fuel repository. TVA isn’t alone. All told, 100 nuclear reactors in 31 states produce 20% of the total electricity in the U.S. Nuclear is a vital part of our nation’s energy mix as we seek enhanced energy security and lower carbon emissions. Pursuant to federal law, the government was directed to begin providing storage for spent nuclear fuel in 1998. That didn’t happen. As a result, reactor owner-operators began suing the federal government for its failure to begin picking up and storing the waste. The government has lost every one of the lawsuits. Now the Treasury has to reimburse reactor owners for the expense of on-site storage. The current cost to the taxpayer for the government’s failure to establish a national repository is estimated to be $20 billion, and growing at a rate of $500 million each year. As House Energy and Commerce Chairman Fred Upton said when the 2011 GAO report on Yucca Mountain was released, “It is alarming for this administration to discard 30 years of research and billions of taxpayer dollars spent, not for technical or safety reasons, but rather to satisfy temporary political calculations.” Nuclear energy is here to stay. It is safe, environmentally friendly, affordable and good for the economy, jobs and manufacturing. But the nation needs a safe repository for used nuclear fuel. When Americans go to vote next month, they have a chance to tell Sen. Reid and Democrats in Washington what they think about people who have seized Yucca Mountain and turned it into a political tool at a huge cost to taxpayers and the environment. Mr. McCullough is a former chairman of the Tennessee Valley Authority and was mayor of Tupelo, Miss. He is now a consultant to energy corporations. Life in the Writings of Storm Jameson By Elizabeth Maslen (Northwestern, 556 pages, $40) I f anyone today reads the British novelist Margaret Storm Jameson (1891-1986)—or is even aware of her existence—the reason may be her resurrection in the early 1980s by Virago Press, when she was herself in her 90s and had long since stopped writing. An imprint dedicated to reviving women authors could hardly have omitted a writer who had provided the literature of her age with such bulk: 65 books, most of them novels, many commercially successful. In “Life in the Writings of Storm Jameson,” Elizabeth Maslen, a research fellow at the University of London, makes rather large claims for Jameson’s work. She groups her with literary “iconoclasts” who go about “dissecting the received wisdoms of their own and the preceding age from a woman’s point of view.” Her novels, Ms. Maslen writes, “are always broad in scope, never tied to the purely provincial, and she is unafraid, like Honoré de Balzac, of analyzing unpleasant characters. She reveals her contemporary world, warts and all. Her sense of the universal embedded in the particular is reminiscent of Stendhal.” The enthusiasm is welcome but goes too far. Although Jameson writes well and displays a feeling for her characters and the society they live in, it is risible to compare her to Balzac or Stendhal—or to Vera Brittain and Rebecca West, two of her contemporaries whose achievement Ms. Maslen regards as roughly similar to Jameson’s own. Jameson is at her best in “A Cup of Tea for Mr. Thorgill” (1957), an exposé of communist intrigue at postwar Oxford, and in “The Green Man” (1952), a family saga that is also a novel of ideas. In those works and in some of her stories, she shows wit and irony and breathes life into overworked forms. From our vantage, she can also be seen as proto-feminist in her concern for women trapped in relationships or worried over their proper role. But for all her occasional virtuosity, the world she conjures can now feel a bit dated. We are likely to infer from “Life in the Writings of Storm Jameson” that the wealth of unpleasant characters in Jameson’s work has something to do with her own less than attractive personality: prickly, worldweary, often just plain sour. Yet, as Ms. Maslen shows, Jameson had the power to attract other writers to her— Rebecca West said that she considered her a sort of sister. And Jameson had a selfless side. She was a champion of newcomers, such as Arthur Koestler and Czeslaw Milosz, and her public stands against censorship and Storm Jameson began writing novels because it ‘was the simplest way to earn money when you have a young child keeping you at home.’ totalitarianism are laudable for their intensity. (She served as president of Britain’s Society of Authors and of PEN International.) Her long-lasting second marriage to Guy Chapman, a distinguished professor of French history, took her to the U.S. and to France for extended periods. She is certainly one of the least parochial of British writers, and some of her works are set in France and depict the character of French life. Yet she never lost the indelible plain-spokenness and direct manner of her native Yorkshire, where she was born to a maritime family: Her grandfather was a ship owner and her father a sea captain. Her childhood was traumatic, dominated by a controlling mother who, she said, thrashed her repeatedly. This experience surely contributed to her rather difficult personality, although, surprisingly, she did develop a strong family feeling. The loss of her brother as a pilot in World War I was a key to her life-long pacifism, and the death of her sister in a bombing raid in 1943 was a painful wound. Her sense of commitment to her only child, a son from a disastrous early marriage, led her to support him—financially and in other ways—through many difficulties in his career and personal life. As Ms. Maslen shows with perhaps too much fidelity, Jameson was often preoccupied with money—or the lack of it. We see her begging for advances, complaining of the unremunerated time involved in writing a long novel, proposing that collections or reprints be published to generate more income. The effect is one of tireless moaning and, for the reader, a certain bafflement. After all, Jameson’s books sold well enough. Early in her career she was recruited by Blanche Knopf, who, with her husband, Alfred, remained her steadfast supporters (and publishers). Looking at Jameson’s career, you can see the particular value of that long-lost figure, the productive midlist author: One of her books was even the featured choice of the Book of the Month Club. Ms. Maslen does not really explain Jameson’s cry of poverty beyond emphasizing her sense of obligation to sundry family members. Was Britain’s punitive tax system perhaps to blame? In her brusque way, Jameson attributed her vast output to financial need. In an introduction to the Virago edition of “Women Against Men”—a gathering of three novellas from the 1930s—the poet Elaine Feinstein wrote that, when she met Jameson in Cambridge in 1981, Jameson insisted that she had “only written novels for money because writing was the simplest way to earn money when you have a young child keeping you at home.” Clearly there was more to Jameson’s writing career than churning out potboilers, even if her first novel was called “The Pot Boils” (1919). But there is a thinness, a want of texture, to her fiction that may well reflect her dispirited attitude toward life. Her books of autography—“No Time Like the Present” (1933) and “Journey From the North” (1969-70)—leave one longing for more about her inner life. Ms. Maslen says that her own aim, in her biography, is “to allow [Jameson’s] personality to emerge from her letters and from comments by her friends.” A few of those who knew Jameson discovered both loyalty and understanding, but the reader of “Life in the Writings of Storm Jameson” may be forgiven for feeling some reservations about the woman we see groaning her way through a long and what should have been a rewarding life. Mr. Rubin is a writer in Pasadena, Calif. P2JW300000-0-A01700-1--------XA By Glenn McCullough Jr. Shades Of Stendahl MAGENTA BLACK CYAN YELLOW

© Copyright 2025