Doing Business in China

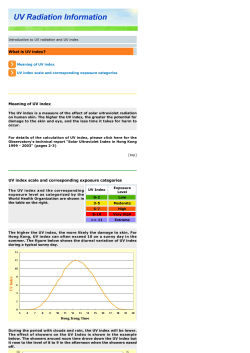

FT SPECIAL REPORT Doing Business in China www.ft.com/reports | @ftreports Tuesday November 4 2014 Slowdown is part of new economic narrative Inside Bribes just one malady in healthcare system Achieving affordability and quality of care is proving to be a struggle Page 2 Driving the car craze Antitrust fines have a wider agenda: to lower prices of vehicles Page 3 Jamil Anderlini says shifts in investment patterns and internal problems signal end to strong growth T he Chinese flag was flying over the New York Stock Exchange in late September as a grinning, elflike former English teacher watched his ecommerce company smash the record for the world’s largest ever initial public offering. Alibaba’s $25bn share sale made Jack Ma the richest man in China, but it also provided the kind of moment that symbolises historic shifts in the global landscape. From outside, China’s rising economic and political power appears unstoppable and relentless. Chinese are now the biggest purchasers of expensive properties in London, New York and Sydney, and Chinese investors are buying up everything from Italian utility companies to the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York City. China’s increasingly assertive Communist leaders seem to want their own version of the United States’ 19th century’s Monroe Doctrine for their own back yard of Asia. This policy stated that any intervention by external powers in the politics of the Americas was seen as a potential hostile act. At the same time, Beijing’s rising influence can be seen around the globe, from Sierra Leone to São Paulo. As he revelled in his company’s successful debut in New York, Mr Ma declared that Alibaba was a company that had already “shaped the world” and said he wanted it to be “bigger than Walmart” as it expands outside its home market. US capitalist investors lapped it up and appeared to have bought into the newest Chinese dream. Alibaba shares Hong Kong protests Beijing’s plans for electoral reform spark fears of long-term impact on business hub Page 4 ended their first trading day up nearly 40 per cent and the company was valued at more than Facebook, Amazon, JPMorgan or Procter & Gamble. Alibaba is not the only Chinese company with dreams of world domination. As growth continues to slow at home, many Chinese companies are looking abroad to make investments, enter foreign markets and acquire valuable technology and brands. But this interest in overseas corporate expansion is increasing just as foreign Rising energy, transport and labour costs squeeze profits Cheap China Local consumers are not prepared to pay the prices that foreign customers will, reports Lucy Hornby Order a child’s Halloween costume in China ($3.44 for pirate hat, eye patch and black cape) and it will arrive at your door the next day, with a mere $1.60 in shipping costs added. If the supplier is in your city, you get it the same day free. This consumer bonanza is increasingly a problem for local and foreign companies selling in China, where rising energy, transport and labour costs are squeezing profits, not just for manufacturers but for the growing number of brands targeting Chinese consumers. For years, the price of labour has been rising, especially for managers, but overall costs were still so low compared with the prices foreign customers would pay that its export industry thrived. By contrast, brands that market to cost-conscious Chinese buyers not only have to manage their manufacturing costs but also contend with shipping and retail costs inside the country. And that in turn means high energy costs are taking a double toll. “Energy costs are so high in China, it’s becoming a concern,” says Shaun Rein, author of The End of Cheap China and managing director of China Market Research Group. Those high costs can show up in unexpected ways as China’s business landscape changes. “Sales have moved so decidedly from bricks and mortar to online that transport is really a problem,” Mr Rein says. For retailers still selling the old fashioned way, the shift from tiny storefronts to malls or box stores has meant higher power costs for air conditioning and lighting, as well as rising rent. Much of the problem lies in China’s industrial structure. “There is not much transparency in how authorities set domestic oil prices and a good system of supervision is not in place,” says Dong Zhengwei, a lawyer and veteran campaigner against state-owned monopolies. “The government wants to protect the interests of large oil companies.” International oil prices dropped by nearly a quarter between late June and mid-October; but Chinese retail petrol Going up: move from tiny storefronts to malls has increased overheads – Bloomberg and diesel prices fell by only half that amount, or 11-12 per cent. The government, which adjusts prices on an irregular basis, is allowing oil companies to recoup some revenues denied them when oil prices were higher. That puts Chinese retail petrol prices about 20 per cent above US prices and diesel prices about 9 per cent higher. Relatively few manufacturers rely on natural gas in China, but those that do have also been facing rising prices. Increases in the state-set natural gas price were designed to offset import losses for state oil companies and encourage them to produce more gas, but the price rises have deterred industrial customers. “It’s one of the few markets in the world where industrial gas prices are higher than residential ‘It’s one of the few markets in the world where industrial gas prices are higher than residential prices’ prices,” says Kim Woodard, an investment adviser in Beijing. Most of China’s industrial sector still relies directly on coal, the cheapest fuel around, but by 2010, 28 per cent of Chinese industry’s energy needs were met by electricity, surpassing the level of industrial electrification in the US. The switch has helped mitigate noxious coal pollution in wealthier cities but made managing energy costs more complicated for Chinese companies. This is important, because power can account for up to 90 per cent of a factory’s cost, depending on the industry. First Financial Daily, a Shanghaibased newspaper, tried to analyse China’s electricity rates last year and concluded there were at least 1,000 tariffs across the country, with 314 in Beijing alone. The result is so confusing it creates a business opportunity. Taryn Sullivan, an American, founded EEx, a consultancy that is helping Chinese factories cut electricity costs by 10 -20 per cent. EEx’s entry-level service is helping clients make sense of their electricity bills. Chinese labour costs are rising steadily as the workforce shrinks, but wages are still well below those in the US, Europe or Japan. The labour-intensive textile industry has already moved to lower-cost markets such as Vietnam or Bangladesh, but for many other industries, especially electronics, China’s ports, roads and clusters of supplier factories make it unattractive to move. Minimum wages are $2.50 an hour in the manufacturing hub of Guangdong (versus $7.25 in the US), although many workers earn more for overtime work during peak order season. The introduction of social security, medical insurance and other programmes has raised costs, although many factories skimp on these legally required payments or deduct other, random fees, from salaries. They also hire “interns” through vocational schools who can legally be paid much less. There is one labour cost that factories are not able to dodge. “Management salaries in China have seen a large increase in the past decade,” says David Alexander, whose Floridabased company BaySource Global advises companies on offshoring. “Where a mid-level manager may have been paid $20,000 about 10 years ago, that position is double that now.” Additional reporting by Owen Guo High stakes: Alibaba’s New York IPO made Jack Ma China’s richestman — Andrew Burton/Getty Images Even the most optimistic forecasters believe China will keep slowing direct investment (FDI) into China is slowing sharply. In recent months, it has fallen at the steepest rate since the height of the global financial crisis, with a drop of 14 per cent in August and a 17 per cent fall in July from the same months a year earlier. Apart from a drop during the financial crisis, FDI inflows to China have grown steadily since the country joined the World Trade Organisation in 2001 and reached a record $118bn in 2013, comContinued on page 2 Financial system in for short-term shocks Liberalisation plans aim to foster longer-term growth Page 5 Internet giants train sights on killer apps Mobile gateway developers become top targets for acquisitions Page 6 2 FINANCIAL TIMES Tuesday 4 November 2014 Doing Business in China Corruption a symptom of healthcare ills Medical system Beijing plans to improve care for its 1.4bn citizens, but distrust of private hospitals is a hurdle, writes Patti Waldmeir Healthcare shortfall Number of licensed doctors for every 1,000 people D oing business in China became that bit more unpredictable when a court hit UK pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline with the largest bribery fine ever imposed on a foreign company in China, while GSK’s British head in China, Mark Reilly, received a suspended three-year prison sentence. Four Chinese managers got sentences of two to three years in a verdict handed down in September. Their sentences were also suspended, but the message was clear, drug industry analysts and insiders say. Foreign drug companies in China can no longer turn a blind eye (or worse) to sales staff who offer bribes to doctors and hospitals that buy their products. Soon after Chinese police began investigating GSK in 2013, the company stopped using individual sales targets as a basis for calculating staff bonuses, globally as well as in China. Other multinational pharmaceutical companies in China have not been so categorical, but industry and legal sources say they have all re-examined their compliance procedures to make sure they are not setting unrealistic sales targets that can only be achieved through what are euphemistically known locally as “commissions”. But punishing one foreign drug company will hardly solve corruption in the Chinese healthcare system, which has eroded public trust in doctors and the objectivity of their treatment choices. Drug industry analysts, doctors and hospital officials all say that local generic companies are more profligate with kickbacks than foreign companies, and that the underfunded hospital system cannot function without them. Local suppliers are still very dependent on such payments, despite the anti- GSK Case timeline Number of outpatient visits (bn) 2.5 8 2.0 6 2013: June 28 Police in Changsha announce that GSK company officials are under investigation for alleged “economic crimes”. July 2 The National Development and Reform Commission, China’s main economic planning agency, announces a probe into the costs of medicines at 60 domestic and international drugmakers. July 11 The Public Security Ministry issues a statement accusing GSK of bribing doctors to prescribe their drugs and concocting a “huge scheme” to raise drug prices. 4 1.5 2004 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 Source: China National Health and Family Planning Commission New start: pharmaceutical multinationals have re-examined their compliance procedures after GlaxoSmithKline was found guilty of bribery — Alexander F Yuan/AP corruption campaign’s efforts to prevent bribery of staff at hospitals. Many doctors say they cannot make ends meet – or live a lifestyle commensurate with being a medical professional – without accepting “gifts” from drug companies, so their incentive to take “commissions” will remain strong, whatever the risk. But bribes to doctors are far from the only problem facing a medical system that must serve 1.4bn increasingly sophisticated, urbanised, demanding – and elderly – patients. China’s leaders have ambitious plans to improve both the quality and affordability of medical care, through complicated reforms of the healthcare system including drug price controls and a radical transformation of health insurance. However, none of this will happen swiftly. Beijing is certainly willing to spend money on the problem, but in 2013 healthcare still accounted for only 6 per cent of gross domestic product, according to national statistics, compared with 10-12 per cent in western Europe and 15-17 per cent in the US – and far less per capita, according to McKinsey. The government promised in 2009 to provide universal, low-cost healthcare within three years. Since then, 95 per cent of the population has been given basic health insurance. However, the coverage is so limited that many families face crippling costs. While public dissatisfaction is high, Beijing sees improving healthcare as critical to maintaining social harmony. However, many interactions between healthcare staff and patients are far from agreeable, with hundreds of attacks on healthcare workers every month. Many doctors say the last thing they want their children to do is study medicine. Beijing hopes to ease the pressures on the public system by doubling the share of private hospitals to 20 per cent by 2015 and private investors are eager to jump on that bandwagon. Private investment in the mainland healthcare sector rose to an all-time high, with deals worth $10bn last year, nearly five times the 2006 figure, according to statistics from Dealogic. So far this year, there have been another $7bn in deals. But public distrust of private hospitals is a hurdle, and they struggle to attract top-quality doctors, who prefer the prestigious state system. Investors may battle to identify potentially profitable deals in a sector where corruption is rife and hospital finances are opaque. Additionally, privatisation will not solve the problems of corruption, overwork, low salaries and conflict in the state hospital system – where most of China will continue to receive its medical treatment. Additional reporting by Zhang Yan July 15 Police say GSK made “illegal” transfers. Gao Feng, head of the economic crimes investigation unit, says four senior Chinese executives from GSK have been held. Aug 15 China’s State Administration for Industry and Commerce says it is investigating possible bribery, fraud and anti-competitive practices in a range of sectors, including the drugs industry. Dec 16 GSK says it is to scrap individual sales targets for commercial staff and will instead link pay to improved patient care and company-wide performance. 2014: Feb 4 GSK says sales of medicines and vaccines in China fell 18 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2013, year on year, after falling 61 per cent in the third quarter. May 14 Chinese police say their investigation shows that GSK as a company and individuals engaged in bribery on a “massive scale”. June 29 GSK says senior executives had been sent a secretly filmed sex tape of the company’s top manager in China shortly before Beijing opened its bribery investigation. Sep 19 GSK says its Chinese unit will pay a fine of about £300m after it is found guilty of bribery. Slowdown is part of new economic narrative Continued from page 1 merce ministry figures show. But inbound FDI is not expected to reach that level again this year and accelerating outbound investment, which hit $108bn in 2013, according to the commerce ministry, is likely to overtake inbound investment within the next year or two. This trend of rising outbound and falling inbound investment suggests a different narrative from the dominant international impression of a relentlessly rising China. Charles Wolf, a China expert and distinguished chair in international economics at the Rand Corporation thinktank, argues that shifts in investment patterns are important for judging economic prospects in a given market. “If we look at inbound and outbound FDI in China and we examine the rates of change, we can see that outbound Chinese investment to Europe and the US is extremely positive, while inbound FDI from those markets and elsewhere to China is now quite negative,” he says. “This shift is indicative of expectations regarding market opportunities and GDP growth,” he adds. In fact, from Beijing’s viewpoint, global perceptions of indomitable Chinese strength seem somewhat far-fetched. The country’s borrowing-to-GDP ratio continues to rise rapidly, even as growth continues to slow. The world’s second-largest economy is almost certain this year to report its weakest annual expansion rate since 1990, when the country still faced international sanctions in the wake of the Tiananmen Square massacre. Owing to the stimulus measures Beijing introduced in the wake of the financial crisis, debt relative to GDP has expanded from about 130 per cent in 2008 to more than 250 per cent by the middle of this year. No economy in history has experienced credit growth of that speed and scale without suffering a financial crisis and a protracted period of low growth. China’s expansion is also being dragged down by a prolonged correction in the property market, which has been the single most important driver of the economy for much of the past decade. Even the most optimistic forecasters Top of the world: Jack Ma’s Alibaba was the largest ever IPO — Andrew Burton/Getty Images believe China will keep slowing in the next few years, even if it is able fully to implement a range of reforms intended to rebalance growth away from an overreliance on investment towards consumption, particularly of services. China faces double-digit wage increases and indeed rising costs across the board that are making the country less and less attractive as the world’s workshop. But it is also becoming less attractive as a market for global businesses and not just because of the falling growth rate. Over the past year, many multinational companies have been hit by a wave of state media attacks and opaque regulatory investigations that have $108 bn China’s outbound investment last year 250 % China’s debt relative to GDP, up from 130% in 2008 sometimes resulted in hefty fines. Many of the world’s largest carmakers, household names from the world of technology, such as Microsoft and Qualcomm, and a host of others from sectors as varied as pharmaceuticals and baby milk formula makers, have been investigated for alleged price fixing and monopolistic activities. The US and EU Chambers of Commerce in China have strongly criticised the heavy-handed “intimidation tactics” of the “discriminatory” government campaign against their members. They have warned that these actions could violate commitments that China made when it joined the World Trade Organisation. Jacob Lew, the US treasury secretary, sent a letter to China’s leaders saying such tactics could have serious implications for broader Sino-US relations. Shaken by the criticism, Chinese premier Li Keqiang responded by saying foreign companies have only been involved in 10 per cent of the anti-monopoly cases brought under the current campaign. No other statistics are publicly available and the claim has been met by deep scepticism among multinational executives, who point out that none of the country’s large state-owned monopolies, which dominate most big industries, have been targeted. Experts on China’s investment policies believe the investigations are part of a broader trend that has developed as the country has shifted from being a cash-starved importer of capital to an exporter of capital. Lei Li, a Beijing-based partner with the law firm Sidley Austin and a former official in the legal department of China’s ministry of commerce, declares: “I can remember the good old days a decade ago, when the Chinese authorities, particularly local governments, welcomed almost any kind of foreign investment.” However, Mr Li says that since 2009 the government has become much more selective about the kinds of investment it wants: “It has imposed more and more conditions on foreign investment and has actively discouraged certain kinds, such as polluting, low-end manufacturing.” Decades from now, the Alibaba IPO will definitely be remembered as a historic symbol of changing fortunes and shifting economic realities. However, those shifts may not go entirely in the direction most people assume they are heading today. 3 FINANCIAL TIMES Tuesday 4 November 2014 Doing Business in China Antitrust fines for foreign car companies fail to stall growth Chinese antitrust fines Largest fines, Rmb million Sumitomo Electric and nine other parts suppliers (Japan) 1,240 Audi JV and dealerships (Germany) 278 Maotai (China) 247 Mead Johnson (US) 304 Fines paid Rmb Wuliangye (China) 202 Sales drive Price probe has not dented profits, reports Tom Mitchell 648.6m Danone Dumex (France) 172 F or multinational car companies operating in China, the euphoria from the biggest ever automotive boom in industrial history is finally being tempered by some unexpected risks, most notably a controversial investigation by the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) into allegedly anti-competitive behaviour by Audi, Mercedes-Benz and other brands. The investigations have so far resulted in fines that are peanuts in comparison to the vast profits that foreign automakers have enjoyed over recent years – and continue to enjoy. In July, a joint venture between Volkswagen unit Audi and state-owned First Auto Works was ordered to pay $41m for alleged violations of China’s 2008 Anti-Monopoly Law. This compares with reported operating profits of $12.2bn for VW’s joint ventures in China (its otheriswithSAICMotor) last year. Fiat unit Chrysler was also hit with a small fine this summer, while Daimler’s joint venture with BAIC Motor, which makes Mercedes-Benz saloons, is still awaiting the outcome of an NDRC investigation after one of its Shanghai sales offices was raided in July. These fines are the byproduct of a wide-ranging investigation that appears to have a much larger aim – forcing car companies, regardless of whether they are in fact guilty of anti-competitive practices, to lower the prices of their vehicles, spare parts and services. According to one industry executive, the head of a multinational company’s China operations has told visiting board members that, in view of the NDRC’s offensive, his biggest fear is of a sudden shift in government policy. “It’s bad for business,” the executive says of the Investigations have so far resulted in fines that are peanuts in comparison to the vast profits that foreign automakers continue to enjoy investigation. “It has made the investment environmentveryuncertain. “If people can afford the cars, they can afford the spare parts and after-sales service,” he adds. “It’s not like the NDCR is lowering the price of medical care or making food cheaper.” Foreign automobile executives argue that the relatively high prices asked for cars – especially premium vehicles that can be almost twice as expensive in China as they are in the US – is a function of unprecedented demand, even for overseas models subject to expensive import taxes. China’s car craze began in earnest in 2008-09, during the depths of the global financial crisis, when it overtook the US as the world’s largest car market. Demand from entire generations of first-time drivers soared in the world’s second-largest economy, just as purchasing power collapsed in the US and Europe – a nadir symbolically marked by Washington’s bailout of General Motors in December 2008. Over the ensuing half decade, foreign carmakers in China, especially long established ones such as Volkswagen and GM, had a licence to print money. Biostime (China) 163 LG (Korea) 118 Lucy Hornby China correspondent Patti Waldmeir Shanghai correspondent Gabriel Wildau Shanghai correspondent Charles Clover Beijing correspondent Tom Mitchell China correspondent Demetri Sevastopulo South China correspondent 2,394.9m Paid by foreign companies Samsung (Korea) 101 Total: Rmb 3,043.6m Trading up: premium vehicles cost almost twice as much as in the US Even last year, when double-digit annual growth was finally expected to taper, annual sales grew by about 15 per cent to 18m passenger cars – 10 times as many as were sold in India. This year began in similar fashion, especially for foreign brands and their Chinese joint venture companies. Sales of Chinese brands, however, began to fall sharply and their share of the passenger car market tumbled from 27 per cent to 23 per cent. The precipitous fall-off in sales of local brands and slower economic growth has forced the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers to lower its projection of an 8.3 per cent increase in year-on-year sales this year to 4.6 per cent – two-thirds down on last year. In the first quarter, Geely, the private sector carmaker most famous for its purchase of Volvo Cars from Ford, saw sales of its own-brand vehicles fall by as much as 40 per cent over the same period a year earlier. This was despite a gradual improvement in the quality of local-brand cars in China, according to Geoff Broderick at JD Power, which publishes an annual customer survey of 212 models across 62 brands. “The domestic brands are doing exactly what they should be doing – focusing on quality,” Mr Broderick says. “But as we see the quality gap closing, we’re not seeing a pick-up in [local brands’] market share.” One reason for the fall has been a counterintuitive NDRC requirement that foreign-invested joint ventures develop a local brand for the China market, such as the Baojun saloon manufactured by GM, SAIC and Wuling. Many of these new entrants are priced to compete against domestic rivals, especially in smaller cities where car ownership rates are relatively low. “I don’t understand what the Chinese government’s objective was in encouraging foreign companies to create local brands,” says Bill Russo, a Shanghaibased industry consultant. “It only cannibalises already distressed sales of local brands. I think the intent was for more technology to be shared by the foreign companies. But the unintended consequence is to take volume from local carmakers producing similar products,” he adds. At the other end of the spectrum, foreign carmakers continue to thrive in saturated markets such as Beijing and Shanghai, where premium brands such as Audi, BMW and Mercedes-Benz account for a quarter of the market. Even now, limits on expensive new licence plates to combat congestion and pollution are spurring their sales, as existing plate holders trade up. “As cities implement plate restrictions, people gravitate towards premium foreign brands,” says Mr Russo. “They want to put their expensive plates on the best piece of automotive technology that they can.” Contributors Jamil Anderlini Beijing bureau chief Paid by Chinese companies Jörg Wuttke President of the EU Chamber of Commerce in China Adam Jezard Commissioning editor Steven Bird Designer Andy Mears Picture Editor For advertising details, contact: Maralyn Ho +852 2905 5580; email: maralyn.ho@ft.com, or your usual FT representative. All FT Reports are available on FT.com at ft.com/reports. Follow us on Twitter @ftreports. Source: China Central Television, NDRC 4 FINANCIAL TIMES Tuesday 4 November 2014 Doing Business in China Hong Kong Fears grow over impact on business of electoral reform plans, reports Demetri Sevastopulo Power of Beijing looms large in territory’s future H ong Kong has witnessed the most heated debate about its political future since Britain handed the territory back to China in 1997. From the end of September, tens of thousands of students and other pro-democracy demonstrators took to the streets to oppose a controversial Chinese plan for electoral reform in the former British colony. The protesters were so successful in blocking traffic in a crucial commercial district that they sparked concerns about the impact on the economy and the city’s reputation as a leading financial centre. The Occupy movement even prompted a rare intervention from Li Ka-shing, Asia’s richest man, who urged the students to return home. “We understand student passion, but your pursuit needs to be guided by wisdom,” the Hong Kong tycoon said recently. “It would be Hong Kong’s greatestsorrowiftheruleoflawbreaksdown.” So far, few protesters appear to have listened, partly because one of their main concerns is that the Chinese plan allows the elites who wield power in Hong Kong to retain far too much influence at the expense of the public. In August, China followed through on a promise to introduce universal suffrage – one person, one vote – for the election of Hong Kong chief executive, the top political job, in 2017. It has urged people in Hong Kong to support the plan – which requires approval from Hong Kong’s legislature – on the grounds that it provides them with a greater political voice than was available during the British colonial period. But critics say tough conditions that Beijing included in the plan mean it amounts to nothing more than “sham democracy”. Those concerns morphed into the physical protests that forced the closure of traffic arteries in the Admiralty district and other shopping and entertainment areas in what has been dubbed the “umbrella revolution” after demonstrators huddled under umbrellas during downpours. While many business people say privately the protests could do lasting damage to the city’s reputation, few have Tide of opinion: while many Hong Kong people are sympathetic towards the protesters, few have been willing to speak out publicly – AFP been willing to speak out. Some are concerned about generating anger among the protesters that might be directed at their businesses. Following a visit to Hong Kong, Stephen Roach, a senior fellow at Yale University’s Jackson Institute for Global Affairs and a former Morgan Stanley Asia economist, said that while the protests were still causing a little inconvenience, they were “not a big deal” in terms of economic impact. Mr Roach said the bigger question was whether there would be any long-term impact on Hong Kong’s reputation as a business hub. At the height of the protests when masses of people were demonstrating on the streets, he said there were signs multinationals might start to look at places such as Singapore as an alternative, but “now that the intensity has diminished, I don’t think it is going to be a significant factor”. He added that as long as the confrontation did not lead to “extreme” police action, “the reputational impact will be minimal”. Some people who are sympathetic to the protesters fear that speaking publicly would earn them the wrath of China, on which they increasingly rely for business deals. For example, Jimmy Lai, the Hong Kong media tycoon who owns the anti-Beijing Apple Daily newspaper, has accused the Hong Kong government of persecuting him in the wake of a move by the anti-graft agency to investigate payments he made to democratic lawmakers who are critical of Beijing. Apple Daily has also accused Standard Chartered and HSBC of pulling advertising because of pressure from Beijing, claims both banks have denied. Even before China unveiled its controversial plan, a Chinese official speaking in Hong Kong gave an unusual warning – for a senior Communist party member – that the territory’s famed capitalist system could come under threat if protesters followed through on their threat to occupy the city. Under the current electoral system, an elite committee of 1,200 people who are mostly loyal to Beijing, elect the chief executive. Beijing is prepared to let 5m people in Hong Kong vote for their leader, but is not prepared to give the public a role in choosing the candidates. The leaders of the democracy move- Beijing is not prepared to give the public a role in choosing the candidates ment in Hong Kong argue that, as a result, the plan on offer does not amount to “genuine” universal suffrage. China has also ruled that potential candidates must secure support of a majority of a nominating committee that is expected to resemble closely the current 1,200-member election committee. At present, candidates need support of only one-eighth of committee members – a formula that has allowed opponents of the Communist party twice to get on the ballot. Critics say the new proposal would be more restrictive, giving Beijing even more scope to ensure itscriticscouldnotrunforelection. At a rally on the day that China unveiled its electoral reform plan, Martin Lee, the founder of Hong Kong’s Democratic party, summed up the concerns of critics when he said the people of Hong Kong wanted “genuine universal suffrage and not democracy with Chinese characteristics”. “Hong Kong people will have one person, one vote, but Beijing will select all the candidates – puppets,” he said. “What is the difference between a rotten apple, a rotten orange and a rotten banana?” Hermès takes long view to feed appetite for understated style Luxury case study Even as Beijing cracks down on extravagance, brand holds its appeal for sophisticates, writes Patti Waldmeir Luxury goods were the currency of Chinese corruption for decades, until Beijing stepped in two years ago to block the flow of fine baubles into the hands of government officials – and stem the flood of profits into the coffers of luxury goods companies. Hermès, the luxury dynasty best known for its sought-after Birkin and Kelly handbags, is one of the few luxury brands that has prospered despite Beijing’s abstemiousness campaign. “So far we haven’t seen any impact on ourfigures,”saysAxelDumas,chiefexecutive of Hermès and scion of the foundingfamily. The French company does not break out mainland sales, but sales in Asia (excluding Japan) rose 17 per cent in the first half of 2014, while first-half sales for its rival LVMH in Asia (excluding Japan) wereuponly3percent. And despite the generally gloomy atmosphere around luxury in China these days, in September Hermès opened its first mainland maison, in Shanghai, to complement those in Paris, New York, Tokyo and Seoul. It might seem like the worst time to do such a thing, but Mr Dumas is not in the least bit worried. That could just be the self-confidence that comes with representing the sixth generation of the company’s founding family. But it is more likely that his optimism reflects a more important underlying fact about why the French luxury group continues to do well in the middle kingdom, despite the most challenging luxury market conditions in a decade. Hermès represents what China aspires to be: not just another nouveau riche nation with more money than taste, but a country of sophisticated affluence and understated extravagance. Mr Dumas thinks time is on the company’s side, as Chinese consumers outgrow their tendency to show off with luxury brands and develop an appetite for savouring them. Most retail analysts agree: Chinese consumers are growing keener on niche Lap of luxury: Hermès’ Shanghai maison took seven years to build top-level brands such as Hermès and less fond of logo-laden, mass luxury rivals such as LVMH and Gucci. Torsten Stocker, retail partner at consultancy AT Kearney in Hong Kong, says: “Hermès’ more classic style fits well with the high-end Chinese consumer’s shift to less ostentatious items.” Cao Weiming, Hermès head in China, agrees: “Two to three years ago, we started to see some changes, even Hermès represents what China aspires to be: not just another nouveau riche nation with more money than taste, but a country of understated affluence before the anti-corruption campaign began, as the market moved naturally toward greater sophistication, where consumers are more brand-knowledgeable than show-off.” That transformation will take time; but that is one thing the French house prides itself on having. It takes many years to train its craftsmen. It takes forever to get through the waiting list to buy a Birkin bag. It even took seven years to build the Shanghai maison. Mr Dumas points out that his family’s connection with China stretches a long way back: his grandmother, who was born in the early 20th century, when many French writers and artists indulged a passion for the “far east”, was a fan of mah-jong. Gestures toward that Chinese heritage pepper the Beijing store, including horse-themed dinnerware for the current lunar year of the horse. Indeed, Hermès is so keen on winning over this market that four years ago it launched its own Chinese luxury brand, Shang Xia– one of the few mainland brands that celebrates its Chineseness, rather than apologising for it. Everything in the Shang Xia collection of clothing, jewellery, furniture and objets d’art has a story: a cashmere felt coat is inspired by the wool felt saddle blankets used by Mongolian horsemen; a jade “ladder to heaven” necklace echoes the bamboo undergarments worn in imperial China to keep heavy ceremonial fabrics away from sweaty skin. It is the first Chinese lifestyle brand built from the ground by a leading European luxury house. Making it a success will take time, even decades. Additional reporting by Zhang Yan 5 FINANCIAL TIMES Tuesday 4 November 2014 Doing Business in China Liberalisation threatens stability in the short term Finance Policy makers set sights on long-term growth and patient investors will find plenty of opportunities, writes Gabriel Wildau G lobal financial institutions are hoping that China’s pledge to liberalise its financial system will bring opportunities in a market that has long stymied their efforts to gain a foothold. Their hopes for swift progress may be dashed, however, as risks from within the system are likely to encourage policy makers to apply the brakes on reform. Last November, Communist party leaders approved a landmark agenda that included pledges to deregulate interest rates and liberalise the flow of investment funds in and out of the country. Their goal was to improve the allocation of financial resources and correct distortions in the economy, putting the country on a secure footing for several more decades of rapid growth. For instance, a cap on bank deposit rates has encouraged excessive investment in infrastructure and manufacturing by keeping borrowing costs artificially low. Meanwhile, overinvestment has led to rampant overcapacity in sectors such as steel, cement and non-ferrous metals, creating a host of unprofitable firms and imperilling the financial sector, as lossmaking companies fail to repay debt. At the same time, restrictive capital controls preventing Chinese citizens from moving funds abroad have trapped savings inside the nation’s borders, further contributing to wasteful domestic investment. This liquidity has also helped inflate a housing bubble, as savers – prevented from buying foreign assets and wary of the casino-like domestic stock market – have embraced bricks and mortar as an investment rather than just a place to live. Deregulation of rates, when it finally occurs, should play to the advantage of foreign banks and joint-venture broker- Freer capital flows will open the door to capital flight if investors lose confidence in the economy ages operating in China, which are experienced at managing interest-rate and foreign-exchange risk. They should also be able to earn profits dealing in derivatives to help clients manage such risks. Freer capital flows would also create opportunities for foreigners, especially overseas asset managers that will enjoy increased access to mainland capital markets. But such freedom may still be years away. Currently, foreign investors are allowed to buy only into China’s domestic stock and bond markets under a strict quotasystemthatseverelylimitsaccess. By comparison, direct investment, which involves buying an overseas company outright or starting an enterprise from scratch, is relatively more open, but still subject to government approval. John Greenwood, chief economist at Invesco, a UK-based fund manager, says: “The gradual relaxation of capital controls should bring multiple opportunities to asset managers, but we must China’s rising debt load Total social financing stock by type, as a % of GDP Critics are disappointed, one year on, at the slow pace of change in this important test area for reforms, writes Gabriel Wildau A year after the launch of the Shanghai “free trade zone”, hailed as a laboratory for ambitious economic and financial reforms, many investors are disappointed at the slow pace of change. However, while critics rightly note that precious few business and investment activities are currently permitted in the zone (known as the FTZ) that are not also allowed in the rest of China, it is too early to dismiss it as a failure. The government has used its first year to establish a regulatory framework for further liberalisation of rules on foreign direct investment and cross-border capital flows. Meaningful deregulation under this framework has been slow, but with the basic infrastructure now in place, the government could proceed quickly to loosen capital controls or open to foreign investment industries that were previously off-limits. “We still hold the view that the Shanghai FTZ and other [similar zones] will be an important test ground for China’s capital account convertibility,” says Ju Wang, senior foreign exchange strategist at HSBC. “Over time, we can expect companies and individuals within the zone to be able to conduct free borrowing and lending activities as well as portfolio investments.” Full convertibility would enable investors to exchange renminbi freely for foreign currency for the purpose of either portfolio or direct investment, without being subject to quotas and onerous administrative approvals. Last December, the central bank’s Shanghai branch issued rules establishing a system of special FTZ bank accounts. Moving funds between these and offshore accounts is already possible with few restrictions, but transfers between FTZ Han Zheng: no finance for finance’s sake Preferential policies in the zone • Simplified company registration: a “one-stop shop” for all steps in the process. • Approach to foreign investment. All industries not on the “negative list” are open to foreigners. • Investment in sectors not on the list via a simple registration system; no advance approvals necessary. • Simplified procedures and less red tape for customs, shipping and logistics to make merchandise trade more convenient. • Unrestricted transfer of funds between FTZ bank accounts and offshore accounts. • Suspension of 14-year ban on games consoles, which can be produced in the zone and sold throughout China. – Qilai Shen/Bloomberg 150 100 50 0 2002 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 Source: CEIC accept that these changes will be slow in coming. Nevertheless, since the Chinese market has huge potential, it is worthwhile being patient.” The problem is that such reforms, while they will aid long-term growth, are likely to be destabilising in the short term. That is a problem for China’s Authorities are taking a cautious approach to Shanghai test ground Trade zone 200 Entrusted loans, corporate bonds, nonfinancial equities, and others Bank and trust loans to local governments Bank and trust loans to corporates, households accounts and the rest of China remain tightly controlled. Yet, with the FTZ account system now in place, the ground is prepared for further opening up of the system. Officials have said they are preparing stress tests to gauge the impact of freer capital-account flows. Nonetheless, investors should be under no illusion that the authorities will allow unfettered flows for financial investment any time soon. Han Zheng, Shanghai Communist Party secretary, said recently: “Convertibility under the capital account does not equate to full convertibility under the capital account. These are different concepts.” He added: “We are opening up capital account operations directly serving the real economic growth, instead of finance for the finance’s sake.” Another example of the government’s cautious approach to reforms in the zone is the much-touted “negative list”. For years, China has regulated foreign direct investment by publishing a catalogue that categorises each sector of the economy as either “encouraged”, “restricted” or “prohibited”. The FTZ has established a mirrorimage system for regulation of foreign investment. All industries not included in the negative list are permitted for foreign investment. Like the FTZ bank account system, the negative list has delivered few practical results so far. ‘It is not a matter of two or three years: many things need to be done’ The initial version of the list contained 190 items, making foreign investment in the zone barely less restrictive than in the rest of China. In late June, the government trimmed 51 items from the list, opening sectors including real estate, oil exploration technology, and chemicals. Officials say that the negative list is likely to be shortened further in the coming years. Yang Xiong, Shanghai’s mayor, has said: “It is not a matter of two or three years. Many things need to be done. But from a long-term perspective, it is the right path.” Patience pays: investors monitor stock prices in Shanghai stability-obsessed leadership, which is therefore likely to implement them more slowly than the most zealous advocates of reform would prefer. Once banks are forced to compete for depositors’ funds, interest rates will rise. That will be painful, given the large increase in corporate and local govern- ment debt since the global financial crisis. Rising rates will also increase the cost of servicing debt, potentially sparking a wave of defaults. Freer capital flows will open the door to capital flight if investors lose confidence in the economy. Such a scenario is all the more likely if rising interest rates spark a wave of defaults among highlyindebted corporate borrowers. To be sure, China has already taken cautious steps to open its financial system. A new programme will allow Hong Kong and Chinese investors to buy into each others’ stock markets. However, this scheme is subject to a strict quota, and authorities have made it clear that “capital-account convertibility” – the technical term for freeing cross-border investment flows – does not mean it is open season for speculative capital to slosh in and out of the territories. “A rapid opening up could be highly destabilising for the economy, so we understand the caution of the authorities,” says Mr Greenwood. 6 ★ FINANCIAL TIMES Tuesday 4 November 2014 Doing Business in China Internet titans focus on staying ahead of mobile revolution Technology Charles Clover says search for gateway apps is driving acquisitions in a dynamic industry T he listing of Alibaba in New York in September created the world’s second-largest internet company by market capitalisation, behind Google. This did not happen by accident. Of the top10 internet companies in the world, ranked by market cap, three are Chinese, and the rest are from the US. Together, Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent form what is know in China as “BAT”. These economic juggernauts that have come to dominate the internet in China are operating almost along the lines of Japan’s keiretsu, which are alliances of businesses with similar interests or that have shareholdings in one another. They are also rapidly branching out into offline sectors, such as transport, travel, retail and banking. Whether the rapid growth of the Chinese internet is just a bubble or a stable trend is open to question. However, for the time being at least, BAT has become the nucleus of an internet industry that is starting to rival the US, creating what is essentially a US-China duopoly. The three Chinese companies also benefit from what has become known as the “Great Firewall”, as most of the top US companies, such as Google, Facebook and Twitter, are excluded from operating in China. However, no Chinese internet company has yet made the leap from China to become a global brand. For now, it is enough for them be dominant in China, which had 632m internet users as of June, 527m of whom go online using mobile devices. The potential of the forecast consumption boom, as China moves from an investment-driven economy to a consumption-driven one, is enough to attract investments such as the $25bn sunk into Alibaba in its initial public offering, the largest ever. The internet is the most dynamic part of China’s budding private sector, though it remains solidly under the control of the state. Foreigners hold large shareholdings in Alibaba, Tencent and Baidu and dozens of other internet companies. But these stakes are largely theo- Changing times: of the 632m internet users in China, 527m go online using mobile devices Ed Jones/AFP/Getty Images retical at best and owned via “variable interest entities”, or VIEs, which guarantee a payment stream from, but not ownership of, the licence-holding vehicles in China. These VIE’s are technically illegal, though Chinese courts turn a blind eye to the practice, and owners know their large holding only exists thanks to the tacit consent of the state. Nimble private internet companies, able to dance circles around the inefficient state-owned enterprises, have begun impromptu liberalising of whole sectors such as financial services. Alibaba’s fund company Yu’e Bao is China’s biggest online money market fund, with Rmb574bn ($93.8bn) worth of assets The internet is a phenomenal wealth generator. Five of the 10 richest men in China are tech moguls, up from none three years ago, according to the Hurun China Rich List, which tracks wealthy individuals. In September, Alibaba founder Jack Ma joined the list in first place and became one of the wealthiest men in the world, with a 7.8 per cent stake in a $230bn company. China needs to be placed at the top of the European Commission’s ‘to do’ list OPINION Jörg Wuttke Ukraine will undoubtedly be the main foreign policy focus for the European Commission’s newly appointed leaders. The importance of this immediate neighbour to the east is obvious. But Jean-Claude Juncker and his administration should place equal – if not greater – emphasis on a country this lies even further east. With the EU exclusively responsible for foreign trade and investment matters since the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty in late 2009, the bloc’s relations with China should be prioritised to reflect the country’s size and its restrictive investment environment. China has contributed substantially more to the world’s economic growth than any other country since the global economic crisis and it has become its largest economy in purchasing power parity terms. Yet China has long adopted an idiosyncratic approach to foreign investment. Unlike the EU, which does not even have a term for classifying investment within its borders as “foreign”, China retains a distinction between external and domestic investment. In doing so, it places conditionality on the opening of its marketplace by prescriptively laying out conditions that accept foreign investment only where it is perceived to serve specific domestic industrial policies. The vast reform agenda outlined a year ago in the so-called Decision of the Communist Party Central Committee’s third plenary session was therefore welcomed by European industry in China for its breadth and boldness. If implemented resolutely, its emphasis on further opening up of its markets could rebalance China’s increasingly precarious economy and level the playing field for European and other foreign companies. While this demonstrates the political will of China’s leaders to push reforms, these will not come into force overnight. Jean-Claude Juncker: setting tone for future engagement The recent spate of investigations into antitrust violations indicates that problems will continue to arise. One is how China investigates tax collection, particularly among foreign companies. The EU’s leaders should be mindful of these difficulties when working out how to engage with China. Foreign businesses have developed a justified wariness of speaking out on controversial topics. So, when the European chamber became the first association to express concern openly about the opacity and lack of due process in China’s enforcement of its competition law over the past year and a half, it was praised for being courageous. Foreign industry needed to voice its concern, for reasons that go well beyond today’s investigations. But this China is now an economic superpower that helps shape global practices and invests overseas should not be done to disparage China’s efforts to improve how it applies its laws. China’s antimonopoly law is one of the cornerstones for strengthening exactly those conditions that are required to rebalance and upgrade the economy. However, non-adherence to legal due processes in antimonopoly investigations risks a situation whereby administrative power not only perversely distorts competition but, in a wider context, endangers the credibility of China’s attempts to be more open and its ability to let the wider market place have a bigger role in the economy. China improved the positive sentiment among foreign companies to an all-time high following the third plenary session last year. It would be a shame if the praise it has earned for this important policy direction is undermined by poor execution. The antimonopoly investigations show that the EU’s political leadership must be ready to engage head on with China on politically prickly trade and investment issues. Such a strategy must be built on a deep and studied understanding of the country’s business environment. The European parliament ought to look closely (and regularly) at Beijing’s trade policies and actions – as happens in the US – in order to make the informed decisions needed to engage with China. At stake are millions of European jobs, a substantial contribution to economic growth, our ability to innovate and the multiple benefits our relationship with China has brought. As China is now an economic superpower that increasingly shapes global practices and invests overseas, it is high time that engagement with the country commands the priority it merits across all the EU’s institutions and member states. This means that the European parliament, the 28 member states and the European Commission speak with one voice and avoid temptations to bow down to China’s economic might in return for short-term gains at the expense of a unified and resultsorientated strategy. Europe’s change in leadership provides an opportunity for this readjustment of its strategy with China. The opportunity within that opportunity is the EU’s continuing negotiation of an ambitious bilateral investment agreement (BIA) with China. The negotiations represent the most important engagement with China on trade and investment policy since China’s accession to the World Trade Organisation in 2001. They also present the EU with a prime opportunity to set the tone for a constructive engagement with China. As explained in the EU-China 2020 Strategic Agenda for Cooperation, the successful conclusion of a comprehensive BIA would convey China’s willingness to engage in a deep and comprehensive trade agreement with the EU. The writer is president of the EU Chamber of Commerce in China Competition between internet companies is fierce, however. With the entire industry switching from desktop devices to mobile ones, many companies risk being left behind if they don’t have a “killer app” that will act as a gateway for mobile users. Alibaba has been searching for just such a feature to challenge the currently undisputed leadership of Tencent, whose WeChat instant messenger has 350m monthly users. WeChat and Tencent’s other messenger, QQ, are the two most popular mobile apps in China, according to iResearch, a Beijing-based internet research firm. In June, Alibaba bought UCWeb, a popular mobile browser company, and the two have developed Shenme, a mobile search engine. They are also working with Quixey, a US-based company in which Alibaba has invested, to design a mobile gateway using Quixey’s app search engine. Francis Bea of PapayaMobile, a Chinese mobile technology company, says Alibaba is attempting to mirror Tencent’s success with WeChat. ‘There is potential for the mobile internet to disrupt the established internet players’ He says: “In as highly competitive a market as China, there is potential for the mobile internet to disrupt established internet players if they don’t manage the transition from desktop to mobile.” Alibaba has spent an estimated $6bn-$8bn in the space of a year on full acquisitions of, or investments in, companies including mobile providers, chain stores, an internet TV company, a maker of electrical appliances, a movie producer, a digital broadcaster and a professional Chinese football team. While attention has focused on Alibaba’s acquisitions, Tencent and Baidu have been on similar spending sprees. Baidu is betting that its stake in Qunar, China’s top travel website by users, and mobile app store 91Wireless.com, will complement its popular search engine to carry it into the mobile age. Tencent has taken a stake in JD.com, China’s second-largest ecommerce platform, and mobile-friendly companies such as restaurant review site Dianping and South Korea’s CJ Games.

© Copyright 2025