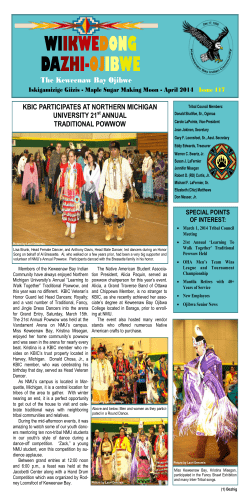

Evaluating the Darfur Peace Agreement