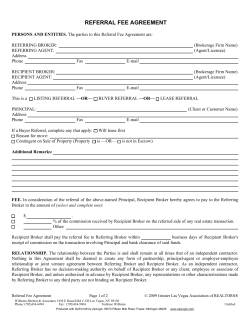

10 Agency