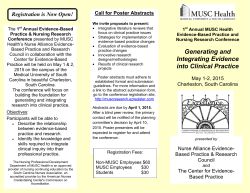

Evidence in Practice On Knowledge Use and Learning in