Document 450474

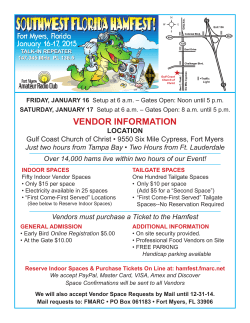

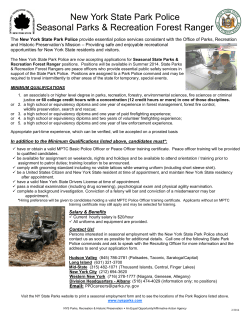

Journal of Planning and Architecture. Photon 106 (2014) 130-138 https://sites.google.com/site/photonfoundationorganization/home/journal-of-planning-and-architecture Review Paper. ISJN: 3715-7618: Impact Index: 3.54 Ph ton Journal of Planning and Architecture Future of children’s play in cities in India V.S. Adane* India Article history: Received: 24 May, 2014 Accepted: 27 May, 2014 Available online: 22 November, 2014 Keywords: Child development, children’s rights, play, playable spaces under threat Corresponding Author: V.S. Adane Abstract India has 440 million children that are more than the entire population of North America [USA, Mexico and Canada put together]. Every fifth child in the world is Indian. And what sort of life do these children have as they grow up? With the growing urbanization and traffic on roads, we find children almost restricted to a few forms of play in limited settings in cities. The Constitution of India upholds the rights of all citizens in unequivocal terms and children are no exception to this. Children’s welfare in the last 60 years has been inextricably woven into women’s welfare and women’s social condition; to an extent, children’s welfare has been subsumed under the composite concept ‘women-and children’. In India where the problems of children are as varied as ranging from health to education to abuse to labor etc., moving the concern now towards children’s most basic right and opportunity to play in cities although seems too unimportant but children’s play provision in cities can help in their education, health and overall development as well. This paper discusses the issues in children’s play in cities which if attended properly can bring in a great change in our future i.e. our children. Citation: Adane V.S., 2014. Future of children’s play in cities in India. Journal of Planning and Architecture. Photon. 106, 130-138 All Rights Reserved with Photon. Photon Ignitor: ISJN37157618D710222112014 1. Introduction Children are designed, by natural selection, to play. Wherever children are free to play, they do. Worldwide, and over the course of history, most such play has occurred outdoors with other children. The extraordinary human propensity to play in childhood, and the value of it, manifests itself most clearly in hunter-gatherer cultures. Anthropologists and other observers have regularly reported that children in such cultures play and explore freely, essentially from dawn to dusk, every day even in their teen years and by doing so they acquire the skills and attitudes required for successful adulthood. 1.1 Children in India Child population encompasses that proportion of the total population of the country which lies in the age group of 0-6 yrs which is an important indicator since it overlooks a delicate segment of the population. India is the second most populous country in the world where 13.12% of her population lies in the tender age bracket of 0-6 yrs as per the provisional census 2011 figures. Ph ton Figure 1: Children’s play As per available data there has been a gradual decline in the share of population in the age group 0-14 from 41.2 to 38.1 per cent during 1971 to 1981 and 36.3 to 30.9 percent during 1991 to 2010, whereas, the proportion of economically active population (15-59 years) has increased from 53.4 to 56.3 percent during 1971 to 1981 and 57.7 to 61.6 per cent during 1991 to 2010. On account of better 130 education, health facilities and increase in life expectancy, the percentage of elderly population (60+) has gone up from 5.3 to 5.7 percent and 6.0 to 7.5 percent respectively during the periods under reference. (Census of India, 2011). Figure 4: Child playing on slide in a park Figure 2: Pie diagram of age structure in India Figure 3: Pie diagram of % of children in various age groups Protection of Life and Personal Liberty (Article (21), Right to Free and Compulsory Education (Article 21A), Prohibition of Child Labour (Article 24), Policies to be followed by the State (Article 39), Provisions of Early Childhood Care and Education (Article 45), The Principle of Non discrimination (Article 2), The Principles of the Best Interest of the Child (Article 3), The Principle of Survival and Development (Article 6), The Principle of Child Participation (Article 12), The Principle of Protection from Abuse and Neglect (Article 19). The state shall protect the child from all forms of maltreatment by parents or others responsible for the care of the child and establish appropriate social programmes for the prevention of the abuse and the treatment of the victims. (ACHR India children’s report, 2003) 1.3 Policies for child development in India National Policy for Children, 1974 An Advisory and Drafting Committee to review the National Policy has been set up to focus on the current priorities with respect to child rights. India has 440 million children that are more than the entire population of North America (USA, Mexico and Canada put together). Every fifth child in the world is Indian. And what sort of life do these children have as they grow up? Well they face some of the toughest challenges of anyone. 1.2 Legal Provisions for Child Development in India The Constitution of India upholds the rights of all citizens in unequivocal terms and children are no exception to this. Important provisions related to children in the Constitution include Principles of Social Justice, Equality and Dignity (Preamble), Right of Equality (Article 14), Prohibition of Discrimination (Article 15(1), National Charter for Children, 2004 The National Charter for Children was adopted on Feb 9, 2004 and promotes highest standards of health and nutrition, provides for free and compulsory education and protects children from economic exploitation. National Plan of Action, 2005 The NPAC envisages a Plan for collective commitment and action by government in partnership with communities, children, and civil society and has set some time‐bound targets for basic sanitation, child marriages, disability due to polio etc. 11th Five Year Plan (2007‐12) Pursuing its thrusts of inclusion, protection, health and education, the 11th Five Year plan lays down the following specific targets with respect to children. National Policy for Persons with Disabilities, 2006 Ph ton 131 With respect to children with disabilities (CWD), this policy looks at right to care, protection, security, development, opportunities, access to education, health, recognition of special needs etc. Policy Framework for Children and AIDS in India, 2007 This policy seeks to integrate services for children with existing development and poverty reduction programmes. Draft National Tribal Policy, 2006, National Rehabilitation and Resettlement Policy, 2007 and National Urban Housing and Habitat Policy, 2007 These policies have sought to look at the specific impact of homelessness, displacement and land alienation of tribal communities on children. Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006, Right to Information Act, 2005. There are a number of Institutional Mechanisms to look into the proper enforcement of the legal provisions in India and they include Ministry of Women and Child Development (MWCD) in 2006, National Commission for the Protection of Child Rights (NCPCR) and the National Human Rights Commission. Figure 5: Children in group playing in open grounds in parks National Child Labour Policy was adopted in 1987 Following the Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act, 1986 The Ministry of Labour and Employment has been implementing the national policy through the establishment of National Child Labour Projects (NCLPs) for the rehabilitation of child workers since 1988. The National Policy on Education (NEP) is a policy formulated by the Government of India to promote education amongst India's people. The policy covers elementary education to colleges in both rural and urban India. The first NEP was promulgated in 1968 by the government of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, and the second by Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi in 1986. (Health bridge report. 2012) 1.4 National Legislations for children’s rights in India The Child Labor (Prohibition and Regulation) Act, 1986, The Factories Act, 1948, The Mines Act, 1952, The Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection) of Children Act,2000, The Minimum Wages Act, 1948, The Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, 2009, The Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan or the Education for All Programme, 2001‐02, The Scheme for Working Children in Need of Care and Protection by the Ministry of Women and Child Development provides non‐formal education, vocational training to working children to facilitate their entry into mainstream education. Some of the new legislations include - Commission for the Protection of Child Rights Act, 2005, The Prohibition of Child Marriage Act (PCMA), 2006, The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005, The Unorganized Workers Social Security Act, 2008, Communal Violence (Prevention, Control and Rehabilitation of Victims) Act, 2005, The Scheduled Tribes and other Ph ton Children’s welfare in the last 60 years has been inextricably woven into women’s welfare and women’s social condition; to an extent, children’s welfare has been subsumed under the composite concept ‘women-and children’. It is hard to peer beyond the tangle of adults who pronounce on children’s ‘needs’ in the context of mother-child relations, and to look clearly at children themselves. It is still more difficult to listen to children seriously. And it is yet more difficult to include children into society rather than excluding them. But these are essential enterprises: we must extricate children, conceptually, from parents, the family and professionals. We must study the social condition of childhood and write children into the script of the social order. Essentially the interlinked reasons for doing this are twofold. Proper understanding of the social order requires consideration of all its members, all social groups. And children, like other minority groups, lack a voice and have a right to be heard and their views taken into account. It is through working towards better understanding of the social condition of childhood that we can provide a firm basis for working towards implementation of their rights. (Thomas, Jones, Efroymson et. al., 2012.) In a country like India where the problems of children are as varied as ranging from health to education to abuse to labor and so on, moving the concern now towards children’s most basic right and opportunity to play in cities although seems too unimportant but children’s play provision in cities can help in their education, health and overall development as well. 132 Table 1: Standards of Town & country planning organization S.no Type Population/unit 1 Tot lot 500 2 Children’s park 2000 3 Neighborhood playground 1000 4 Neighborhood park 5000 Source – TCP Area req.[ha] 0.05 0.2 0.2 0.8 Hence a concern for children’s play provisions is essential. More so there are a number of issues of children’s play in cities. Table 2- Guidelines set by UDPFI Planning unit Housing cluster Sector/Neighborhood Community District Sub-city center Overall town/city level Source- UDPFI guidelines Area in sq.m per person 3-4 local parks & playgrounds 3-4 local parks & playgrounds 2-3 community level parks & open spaces 1 district level park & sports center,maidan 1 city level park,sports complex,botanical/zoo garden 10 - 12 sq.m. per person If we say child, the very first thing that comes to mind is play, but in all of the legal provisions made so far, this word does not appear , maybe it is hidden in words like facilities and opportunities for children which still awaits to be interpreted in a right way. Apart from the legal provisions there are also some planning provisions made by the TCPO, UDPFI and MRTP Act which lays down some standards of the minimum play areas that need to be provided in any city while making the development plan. The following tables give us an idea about the play provisions that can be given in regard to population, catchment area, scale and intensity of use of play areas etc. In light of the existing facts about children in India, the legislations ,policies, planning provisions made for children, open playable spaces and the values attached to these play spaces in cities, it’s also now important to know about play as an activity in children’s life. 2. What is play? Figure 6: Children playing in open grounds in Neighbourhood Intrinsically motivated Controlled by the players Concerned with process than product Non-literal Free of externally imposed rules Chara cteriz ed by the active engagement of the players These characteristics now frame much of the scholarly work on children’s play. Play is a meaningful experience and tremendously satisfying- pursuit children seek out eagerly and one they find endlessly absorbing. Play is paradoxical – it is serious and non-serious, real and not real, apparently purposeless and yet essential to development. Children have their own definitions of play and their own deeply serious and purposeful goals. These definitions taken together give us a glimpse of the complexity and depth of the phenomenon of children’s play. In a much quoted review of play theory and research, authors Rubin, Fein and Vandenberg draw together existing psychological definitions, developing a consensus around a definition of play behavior as- There are many forms of play in childhood variously described as exploratory play, object play, construction play, physical play [sensorimotor play], rough and tumble play, dramatic play (solitary pretense), socio-dramatic play, fantasy Ph ton 133 play, make believe or symbolic play, games with rules and games with invented rules (Hewes. ParJane. Let the children play: Nature’s answer to early learning, 2005). Play is self chosen, for the pleasure and interest of the player only. Play has, furthermore, been described as a frame of mind or an approach to action, rather than an activity or action itself (Bruner in National Playing Fields Association, 2000). Table 3: Defining the kinds of play S.no. Kinds of play 1 Exploratory/sensory/object play 2 Dramatic play 3 Construction play 4 Physical play 5 Socio-dramatic play 6 Games with rules 7 Games with invented rules Description Exploring objects and environments with touch,mouthing,tossing,banging,squeezing etc. Imaginative play, inventing scripts,playing roles with support of action figures,cars, dolls etc. Build and construct with commercial toyswith found and recycled materials. Rough and tumble play like running,climbing,sliding,jumping etc. Enact social roles and scripts with friends in small groups. Play formal games in social groups with rules like cards,board games etc. Invent their own games with rules in self-organized groups. Age range 0-2.5 yrs 3-8 yrs 3-8 yrs 3-8 yrs 3-6 yrs 5 yrs and up 5-8 yrs. Source – Play England report, 2009 2.1 The importance of play Children’s play is easy to recognize, but notoriously difficult to define. Play deals with feelings as varied as curiosity, pleasure, seriousness and creativity. Play can be physical or intellectual, social or solitary, but “in retrospect it is always remembered as fun” (Rennie.et.al 2003). The literature on play highlights that play has a fundamental impact on children’s healthy growth and development, as it allows them to discover, explore and test their environment and make sense of it. Playful behavior promotes learning and concentration, in addition to encouraging the development of social skills and an ability to manage risk. Most parents and educators agree that outdoor play is a natural and critical part of a child’s healthy development. Through freely chosen outdoor play activities children learn some of the skills necessary for adult life, including social competence, problem solving, creative thinking, and safety skills (Miller, 1989; Rivkin 1995, 2000; Moore & Wong, 1997). When playing outdoors, children grow emotionally and academically by developing an appreciation for the environment, participating in imaginative play, developing initiative, and acquiring an understanding of basic academic concepts such as investigating the property of objects and of how to use simple tools Ph ton to accomplish a task (Kosanke & Warner, 1990; Guddemi & Eriksen, 1992; Singer & Singer, 2000). Outdoor play also offers children opportunities to explore their community; Figure 7: Children playing on streets on a rainy day enjoy sensory experiences with dirt, water, sand, and mud; find or create their own places for play; collect objects and develop hobbies; and increase their liking for physical activity. In fact, research shows that between the ages of three and 12 a child’s body experiences its greatest physical growth, as demonstrated by the child’s urge to run, climb, and jump in outdoor spaces (Noland et al, 1990; Kalish, 1995; Cooper et al, 1999; Janz et al, 2000). Such vigorous movements and play activities can not only enhance muscle growth, but also support the growth of the child’s heart and lungs as well as all other vital organs essential for normal physical development. For example, active 134 play stimulates the child’s digestive system and helps improve appetite, ensuring continued strength and bodily growth (Clements, 1998; Pica, 2003). Vigorous outdoor play activities also increase the growth and development of the fundamental nervous centers in the brain for clearer thought and increased learning abilities (Hannaford, 1995; Clements, 1998; Gabbard, 1998; Jenson, 2000). As per the studies done by researchers in India like Pandya Y. and Priya C. the built environments in the Indian context have spatial configurations such that they encourage streets as spaces to socialize and play which also correlates with the findings of the international studies that children prefer places that are busier and frequented not only by other children but by people of all ages. However, besides these benefits, it is generally accepted that children do not play to achieve an external reward or goal, but because they want to play (National Playing Fields Association, 2000). 2.2 Value of the playable spaces Parks have long been recognized as major contributors to the physical and aesthetic quality of urban neighborhoods. But a new, broader view of parks has recently been emerging. This new view goes well beyond the traditional value of parks as places of recreation and visual assets to communities, and focuses on how policymakers, practitioners, and the public can begin to think about parks as valuable contributors to larger urban policy objectives, such as job opportunities, youth development, public health, and community building. Of the various values attached to playable spaces, the social value of playable spaces is worth mentioning which is as follows Communities Parks and playgrounds provide communities with a sense of place and belonging, opportunities for recreation, health and fitness, events that reinforce social cohesion and inclusive society and offer an escape from the stresses and strains of modern urban living. Perhaps more significantly, the acts of improving, renewing or even saving a park can build extraordinary levels of social capital in a neighborhood. Families and Children Examinations of family leisure have consistently demonstrated a positive relationship between involvement in family recreation and aspects of family strength. It has been suggested that in modern society, leisure is the single most important force developing cohesive, healthy relationships between husbands and wives and between parents and their children. As a freely available, highly accessible local facility providing recreational opportunities for all ages, quality parks and green Ph ton space can make a vital contribution to this relationship building process. Culture and Sport Parks and open spaces enable individuals to revive their creativeness. They are the heart and soul of cities; often retelling our heritage and injecting life into the built environment. Many of our parks and green spaces have an element of historic association such as the name, a monument or commemorative features, with most telling the stories of the local community. Consequently, they imbue the area with a distinctive character and contribute significantly to tourism. The historic environment has a positive and profound relationship to peoples’ sense of place; which in turn can have many positive benefits including increased sense of identity and pride. Crime and Policing High quality maintenance of public space should be integral to strategies for enabling the police to deal with the crime and anti-social behavior that blights peoples’ lives. Equalities Everyone should have access to good green spaces irrespective of ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, disability, age or religion. Despite much equality legislation, it is often the least advantaged who are worst served by a standard service. Social Care and Disability Green spaces that have on site staff teams such as city farms, community gardens, Country Parks, Woodland and Wildlife Trusts, can be particularly useful environments for people with social care needs. They can provide a safe, risk-managed environment, often with specialist staff, facilities, equipment or programmes aimed at those disadvantaged by physical or mental difficulties. Older People Parks are age proof and bring opportunities for physical activity, volunteering and social interaction all of which provide a sense of achievement and purpose. Physical activity does not end with later life. It enables the continued enjoyment of activities of daily living and helps to maintain an individual‘s social networks. Education Schools, particularly in urban areas, have long used parks and green spaces to access the natural environment as a means of education. Parks provide the opportunity for play, exploration and the development of an awareness and understanding of risk in a dynamic, interactive, accessible and free outdoor classroom. 135 3. Issues in children’s play with growing urbanization Adults can enhance and facilitate children’s play but are unable to force children to play. This explains why the same activity in one situation generates play and free play is absent in another situation. While stimulating play opportunities benefit the children, an absence of such opportunities may also result in negative consequences for the affected child. A continuing lack of sensory stimulation is sometimes referred to as play deprivation (Hughes 2003). Although the literature on the subject of play deprivation is limited, it has been suggested that play deprived children show symptoms of withdrawal, impaired concentration, anti-social or aggressive behavior and poor social skills (National Playing Fields Association, 2000; Hughes, 2003; Rennie 2003). However, play allows children to make mistakes and fail tasks and it helps them to recognize their limitations, as well as discover their abilities. If play becomes too safe, it is not only predictable and boring, it also limits children’s practical experiences of risk management, and hence their ability to recognize and deal with risky situations. “The outcome of a more rigidly controlled play environment will result in children being unable to deal with hazardous situations themselves in later life” (Play Wales, 2000). In a public atmosphere where children’s safety is valued over their freedom of mobility, such limitations may have adverse long-term impacts on children’s physical health, as well as emotional well-being (Gill, 1996). Figure 8: Children’s restricted doorstep play The biggest issue and challenges in children’s play lies in the fact that adults today fail to understand the importance and meaning of play. More apparently in the current lifestyle in cities, play is regarded by adults as a futile and purposeless activity that’s only a waste of time of children, who are poor victims of long distances to be travelled in buses to school, hovering syllabi of board education, which in the context of upgrading the syllabus overburdens a child with an advanced course material. If play always and exclusively serves adult educational goals, it is no longer play from the child’s perspective. It becomes work, albeit playfully organized. Increased anxieties about safety and security on the part of some parents have restricted the free movement of children around their neighborhoods and only added to the lure of games consoles, so school visits to outdoor locations are more important than ever. Play is an essential part of the physical, emotional and psychological development of any child, but in urban environments the opportunities for play are restricted. With the growing urbanization, the rate of construction is also very high and the open spaces which acted as substitutes to parks and playgrounds now stand converted to sites for dumping construction material, parking lots, hawker’s area, unauthorized markets etc. Today, the urban park is the primary outdoor environment that still remains for children to meet and play in a sociable and informal setting, where there is still scope for imagination, improvisation and innovation. Play is not grown out of quickly. There are positive benefits to indulging in play whatever your age; teenagers need to play and socially interact just as much as younger children. Many parks and green spaces, in partnership with local authority Children‘s Services, may act as the venues for formalized after school clubs and holiday play schemes. Without such schemes being available within the immediate locality, many working parents from the surrounding communities would be forced to make difficult choices between their on-going employment and career development and the care of their children. This is parks and green spaces again making a useful contribution to local economies. Parents and other adults are often overly concerned with issues such as safety and educational learning, to the extent where free play becomes very limited. This is especially the case with outdoor play, where parents’ fears about traffic accidents and strangers cause restrictions on the opportunities children have for exploring their local physical environment independently. Ph ton Again the availability of these spaces to children and their access to the benefits they bring depends on the ability of the parks team to deliver a safe, quality environment. In recent decades, the trend has been for parents to be more concerned about the dangers faced by unaccompanied children as they explore the environment outside of the home. Even a comparatively minor erosion of a parent‘s 136 perceptions about the quality and safety of the local park, can be enough to discourage a parent from allowing their child to visit alone. Conclusions In the current climate about the growing urbanization, changes in land use in cities in India, changes in the social values, changing age structures, technological advancements, changing psychological and emotional needs of people and society, the holistic development of our future i.e. our children has come to a standstill. It is now the time for childhood educators, parents, play advocates and researchers to do the following – Create the tools to assess the quality of play environments and experiences in various communities in the city. Educate and create awareness and clear misconceptions among adults at community level about child rights and play Introducing the play provisions of children as community level efforts by the municipal corporations and public-private-partnership schemes to maintain and look after them. Creating provisions to grade the communities and allotting incentives by the local authorities for maintaining the same. Working out policies and strategies for provisions in the new residential developments towards well maintained and accessible play provisions. It is high time now to take due cognizance of the situation in the cities and act upon the solutions in view of healthy children development in cities. Research Highlights The paper gives an overview of existing laws and legislations in constitution and planning provisions in cities in India. It highlights the existing condition and people’s outlook towards play in cities. It tries to bring forth value of play for children and raise concern for our role and responsibilities. Recommendations Create the tools to assess the quality of play environments and experiences in various communities in the city. Educate and create awareness and clear misconceptions among adults at community level about child rights and play Funding and Policy Aspects Introducing the play provisions of children as community level efforts by the municipal corporations and public-private-partnership schemes to maintain and look after them. Creating provisions to grade the communities and allotting incentives by the local authorities for maintaining the same. Working out policies and strategies for provisions in the new residential developments towards well maintained and accessible play provisions. Author’s Interests Contribution and Competing With this review paper highlighting the issues in children’s play, it is time now to take due cognizance of the situation in the neighborhoods in cities in India and act upon the solutions in regard to the overall wellbeing of our children. Acknowledgement I would like to thank my guide Dr.V.S.Adane for his guidance and support. I am also grateful to Prof. Gadkari, Prof.Purohit, Prof. Gujarkar and my seniors and colleagues at IDEAS, Nagpur for all their encouragement and goodwill. References Alanen, L., Modern Childhood? Exploring the Child Question in Sociology, Research Report 50 (Finland: University of Jyvaskyla, 1992). Alderson, P., Listening to Children: Children, Ethics and Social Research (London: Barnardos, 1993). Limitations Bartlett S., Hart R., Satterthwaite D., De la Barra X., and Missair A. (1999), Cities for Children: Children’s Rights, Poverty and Urban Management, London, Earth scan. The research points towards need of legal provisions and strategies for play for children at community level in cities but does not seek for solutions or applications of research on residential areas. Christensen P. And O'Brien M. (Eds.) (2003), Children in the City: Home, Neighborhood and Community, London, Routledge. Census of India, 2011 Christensen, P. and A. James (eds.), Research with Children (London: Falmer, 2000). Ph ton 137 Corsten, M., The Time of Generations, Time and Society 1999 (8(2)), 249–272. Mayall, B., Children, Health and the Social Order (Buckingham: Open University Press, 1996). Driskell D. (2002), Creating Better Cities with Children and Youth: A Manual for Participation, Paris, London, UNESCO Publishing/Earthscan Erikson, E., Children and Society (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1965). Mayall, B., G. Bendelow, S. Barker, P. Storey and M. Veltman, Children’s Health in Primary Schools (Buckingham: Open University Press, 1996). Hendrick, H., Child Welfare: England 1872–1989 (London: Routledge, 1994). Hodgkin, R. and P. Newell, Effective Government Structures for Children (London: Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, 1996). Hughes, J., The Philosopher’s Child, in M. Griffiths and M. Whitford (eds.), op. cit. (1988). James, A. and A. Prout (eds.), Constructing and Reconstructing Childhood. Contemporary Issues in the Sociological Study of Childhood (London: Falmer Press, 1990. Second Edition, 1997). Kelley, P., B. Mayall and S. Hood, Children’s Accounts of Risk, Childhood 1997 (4(3)), 305–324. Key, E., The Century of the Child (London: G.P. Putnam’s and Sons, 1909 [1900]). Mannheim, K., The Problem of Generations, in K. Mannheim (ed.), Essays in the Sociology of Knowledge (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1958 [1928]). Mayall, B., Negotiating Health: Children at Home and Primary School (London: Cassell, 1994a). Mayall, B., Children in Action at Home and School, in B. Mayall (ed.), Children’s Childhoods: Observed and Experienced (London: Falmer, 1994b). Ph ton O’Neill, J., The Missing Child in Liberal Theory (Toronto/London: University of Toronto Press, 1994). Pilcher, J., Mannheim’s Sociology of Generations: An Undervalued Legacy, British Journal of Sociology 1994 (45(3)), 481–495. Robinson, J., A Model of Accumulation, in J. Robinson (ed.), Essays in the Theory of Economic Growth (London: Macmillan & Co., 1963), pp. 22–87. Sinclair R. (ed.), Special Edition on Social Research with Children, Children and Society 1996 (10(2)). Skelton t. And Valentine G. (Eds.) (1998), Cool Places: Geographies of Youth Cultures, London, Routledge. Smith, D.E., The Everyday World as Problematic: Towards a Feminist Sociology (Buckingham: Open University Press, 1988). Stephens, S. (ed.), Children and the Politics of Culture (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995). Woodhead M., Psychology and Social Construction of Children’s Needs, in A. James and A. Prout (eds.), op. cit. (1990/1997). Woodhead, M., Children’s Perspectives on Their Working Lives (Stockholm: Radda Barnen, 1998). www.googleimages.com 138

© Copyright 2025