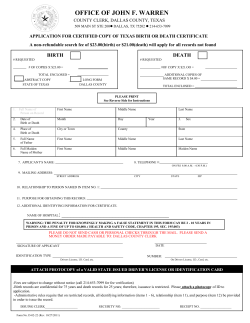

Document 52555