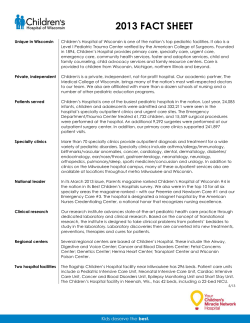

The Healthy Tomorrows Partnership for Children Program