Update: Treatment of Cutaneous Viral Warts in Children REVIEW

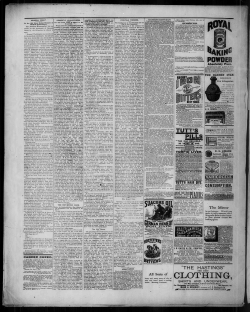

REVIEW Pediatric Dermatology Vol. 28 No. 3 217–229, 2011 Update: Treatment of Cutaneous Viral Warts in Children Christina Boull, M.D.,* and David Groth, M.D. *Department of Medicine-Pediatrics, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, Department of Dermatology, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota Abstract: Warts remain one of the most common reasons for dermatology and primary care visits, yet no definitive therapy is available. Treatment of pediatric patients adds additional challenges, as the adept provider must effectively manage parents’ expectations and patients’ fears. This article provides an update on research in the field of viral cutaneous wart therapies with a focus on pediatric patients. Safety issues and potential complications of therapy are also addressed. Despite rigorous investigation, a definitive treatment for viral warts remains elusive. No single therapy cures all warts, and so potential treatment modalities proliferate. Up to one-third of primary schoolchildren have warts (1), and an estimated 9.1% to 21.7% of dermatology referrals are for cutaneous wart treatment (2). Therapies for children must be safe and preferably painless. This is especially important, as up to two-thirds of warts clear without treatment within 2 years (3), and therapies should not increase morbidity. Many warts, however, do not quickly self-resolve and are associated with decreased quality of life, embarrassment, and physical discomfort (4). Treatment of warts, particularly in children, relies on both the art and science of medicine. In practice, many warts will require treatment with a combination of therapies. Also, as most modalities are user-dependent, individual practitioners may experience higher or lower success rates compared to what is reported in the literature. Whatever the method, the importance of having a calm physician and supportive parent at the bedside cannot be overemphasized. Since the last pediatric review (5) in 2002, additional research has added to our understanding of wart therapies. Randomized controlled trials are still lacking, but this update will highlight the most recent and highest quality studies that have potential relevance to treating the child with warts. Studies pertaining exclusively to immunocompromised patients will not be a focus of this article, as this group has unique treatment needs. Referenced studies include pediatric patients or a combination of pediatric and adult patients unless otherwise noted. DESTRUCTIVE METHODS Destructive methods cause nonselective damage to infected keratinocytes and surrounding cells. Electrodesiccation and curettage in particular leads to wider zones of injury. Although very useful in the treatment of filiform warts or small individual lesions, it should not be considered a mainstay of therapy in children. Destructive methods tend to have high recurrence rates, and parents’ expectations should be set accordingly. Address correspondence to Christina Boull, M.D., Department of Medicine-Pediatrics, University of Minnesota, 420 Delaware Street SE, Minneapolis, MN 55455, or e-mail: oehr0005@umn.edu. DOI: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01378.x 2011 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. 217 218 Pediatric Dermatology Vol. 28 No. 3 May ⁄ June 2011 Salicylic Acid Duct Tape Salicylic acid remains the best tested wart therapy. A systematic review pooling data from six placebo controlled trials of salicylic acid for warts in adults and children showed a cure rate of 75% compared with 48% in controls (odds ratio 3.91, 95% confidence interval 2.4– 6.36) (6). A Cochrane Review (7) comments that ‘‘there is certainly evidence that simple treatments containing salicylic acid have a therapeutic effect.’’ For optimal effect, warts may be pared down with an emery board or pumice stone and covered with a patch to maintain good contact. Salicylic acid should be used very cautiously on facial warts due to risk of scarring. In addition to the variety of over-the-counter products available, pharmacists can be directed to compound higher concentration formulations. We find that Aquaphor compounded with 30% to 40% salicylic acid can be quite effective for multiple and hyperkeratotic warts. Duct tape gained interest in 2002 when Focht et al (11) reported that in 60 children, wart treatment with silver duct tape was significantly more effective than cryotherapy. Eighty-five percent (22 ⁄ 26) of the patients using duct-tape therapy had complete resolution of their warts compared to 60% (15 ⁄ 25) of patients receiving cryotherapy after 2 months of therapy (p = 0.05). More rigorous blinded controlled follow-up studies by de Haen et al (12) and Wenner et al (13) of children and adults, respectively, found no statistical benefit of duct tape over placebo. Notably, silver duct tape was used by Focht, and clear duct tape was used by the de Hean and Wenner groups. This difference may be a factor in the discrepancy among outcomes. Success of home-applied wart therapies depends on the motivation of both the family and the patient. Treatments are frequent and can be time-intensive, but the benefit of therapy may rely as much on the ritual as on the medicinal value. Successful use, however, will prevent the necessity for more painful second-line treatments. Cantharidin Cantharidin, a blistering agent derived from beetles, triggers the release of proteases, which degrade desmosomal attachments leading to acantholysis. Due to the intraepidermal location of the lysis, lesions heal without scarring (8). Cantharidin 0.7% preparation is applied to the lesion topically in the office, covered, and washed off anywhere from 2 to 12 hours later. Patients experience blistering within 24 to 48 hours, and longer application time leads to more blistering. One case of lymphangitis has been reported following treatment. Cantharidin should only be applied in the office, as ingestion has led to severe toxicity and death. In a recent case series, 15 of 15 patients with recalcitrant facial flat warts treated with cantharidin had complete resolution after a mean of 2.6 treatments, and no significant complications or scarring were reported (9). Combination therapy with a compound of cantharidin 1%, salicylic acid 30%, and podophyllotoxin 5% (Cantharone Plus) followed by debridement showed a 95.8% cure rate for plantar warts at 6 months in 144 adults and children (10). Most patients (86.8%) required only one treatment. Although wart enlargement within a few months following treatment can occur with any destructive modality, in our experience it occurs more frequently with this preparation. As with other cantharidin-containing products, it is painlessly applied in clinic, but parents should be advised that significant blistering may occur within 24 hours. Of note, cantharidin is not FDA approved in the United States and so must be compounded by a pharmacist or purchased online from Canada where it is available over the counter. Cryotherapy Gibbs et al (6) analyzed data from 16 trials of cryotherapy published between 1976 and 2001 in a systematic review and found that studies comparing cryotherapy to placebo showed no significant difference in cure rates. Trials comparing cryotherapy to a myriad of other wart treatments noted complete wart resolution rates of 33% to 93% for cryotherapy alone, and 29% to 75% when used in conjunction with salicylic and lactic acid. A Cochrane Review (7) concluded, ‘‘there is less evidence for the efficacy of cryotherapy (than for salicylic acid treatments) but reasonable evidence that it is only of equivalent efficacy to simpler and safer treatments.’’ Nevertheless, cure rates are likely operator dependent. Other investigations into the best techniques for delivery of cryotherapy have found that the use of a cryotherapy gun is not superior to cotton-wool buds for application of liquid nitrogen (13). Longer freezing cycles lead to higher cure rate but produce more pain and blistering (14). Reported complications include hemorrhagic blistering, hypopigmentation, nail dystrophy in periungual areas, and, rarely, short-term neuropathy when used on digits. We believe that despite no proven benefit in efficacy, children find cotton-wool buds to be less intimidating than spray guns. We freeze aggressively to minimize the child’s need for additional office visits. Case series Cantharidin de Bengoa Vallejo et al (10) Open Open Open Case series Case series Open Case series Case series Cryotherapy Ahmed et al (14) Connolly et al (15) Pulsed Dye Laser Robson et al (17) Vargas et al (20) Kopera (18) Akarsu et al (23) Park et al (22) Schellhaas et al (19) Sethuraman et al (21) Blinded Wenner et al (13) Recalcitrant facial flat warts Plantar warts Wart description* 56 children 134 adults and children 19 adults and children 12 adults 40 adults 363 adults and children 200 adults and children Recalcitrant hand and foot warts Recalcitrant warts, any location Anogenital warts excluded Non-anogenital warts PDL PDL PDL PDL versus PDL + SA PDL Any location Facial flat warts PDL versus cantharidin and ⁄ or cryotherapy PDL Cryo gun versus cotton wool buds 10 s freeze versus ‘‘gentle’’ freeze Recalcitrant and non-recalcitrant warts on any site Hand and foot warts Hand and foot warts Outcomes 6 weeks Cure in 8 ⁄ 51 (16%) versus 3 ⁄ 52 (6%) Cure in 8 ⁄ 39 (21%) versus 9 ⁄ 41 (22%) Cure in 46 ⁄ 61 (75%) Cure in 18 ⁄ 56 (32%) patients and 99 ⁄ 206 (48%) warts Cure in 89% Cure in 22 ⁄ 33 (67%) versus 23 ⁄ 33 (70%) warts Up to 12 treatments (2 wks) Avg no. of treatments = 3.1 (2.5–4 wks) Up to 5 treatments (2–3 wks) Up to 3 treatments (3–4 wks) 3.38 avg no. of tx (3.26 wks avg) Up to 5 treatments (4 wks) Cure in 12 ⁄ 12 (100%) Cure in 63% Up to 4 treatments (1 mo) Cure in 66% versus 70% Cure in 39 ⁄ 158 (44%) 3 months (2 wks) versus 55 ⁄ 118 (47%) Cure in 42 ⁄ 71 (59%) versus Up to 5 25 ⁄ 75 (33%) treaments (2 wks) 8 weeks 8 weeks 16 weeks (3 wks) Up to 4 treatments (15–20 days) Duration of treatment and (time between treatments) Cure in 22 ⁄ 26 (85%) versus 15 ⁄ 25 (60%) Topical 138 ⁄ 144 (96%) cantharidin 1%, SA 30%, and podophyllotoxin 5%. 0.7% cantharidin Cure in 12 ⁄ 12 (100%) applications Intervention 60 children and Facial, anogenital, and Duct tape versus adolescents periungual cryotherapy warts excluded 103 children Facial and anogenital Duct tape versus warts excluded placebo patch 90 adults Anogenital Duct tape versus warts excluded placebo patch 15 adults 144 adults and children Participants 73 adults and children Retrospective 61 adults case series and children Blinded de Haen et al (12) Kartal Case series Durmazlar et al (9) Duct Tape Focht et al (11) Open Design Reference TABLE 1. Details of Referenced Trials Absolute numbers not reported Less treatments needed for face and perineal warts Absolute numbers not reported Less laser treatments required in SA group Absolute numbers not reported 43% default rate Clear duct tape Clear duct tape 9 patients lost to follow-up Notes Boull and Groth: Update: Treatment of Warts 219 Blinded Grussendorf-Conen and Jacobs (44) Micali et al (45) Case series Case series 5% imiquimod 5% imiquimod 5% imiquimod Imiquimod Hengge et al (43) 50 adults Anogenital and children warts excluded 18 children Recalcitrant, non-anogenital warts 15 adults Recalcitrant sub and children and periungual warts Case series Gamil et al (39) Injections Single blinded 233 adults Mostly recalcitrant warts, Antigen ± and children location not reported interferon versus interferon or saline Case series 23 adults Plantar warts MMR injection Recalcitrant acral warts Horn et al (38) 47 children 3 months Cure in 9 ⁄ 28 (32%) versus 8 ⁄ 26 (31%) Cure in 10 ⁄ 27 (37%) versus 4 ⁄ 16 (25%) 2 months Cure in 25 ⁄ 32 (78%) versus 3 ⁄ 23 (13%) Up to 16 weeks Up to 12 months Up to 16 weeks Cure in 16 ⁄ 18 (89%) Cure in 12 ⁄ 15 (80%) Up to 3 treatments (3 wks) Cure in 15 ⁄ 50 (30%) Cure in 20 ⁄ 23 (87%) Cure in 56% versus 23% Cure in 22 ⁄ 47 (47%) 46% drop out rate; all patients zinc deficient Better clearance in younger patients 12 patients with transient pigment changes 16 patients were immunosuppressed 43% drop out rate Unspecified no. of Higher distant injections (3 wks) ⁄ Up cure rate with to 10 treatments antigen treated warts of cryo (3 wks) 3.78 avg no. of treatments (3 wks) Up to 5 Absolute values treatments (3 wks) not given; intention to treat analysis 2 months Cure in 20 ⁄ 23 (87%) versus 0 ⁄ 20 (0%) 12 weeks 2 months Cure in 26 ⁄ 32 (81%) (15 days) (2–4 wks) (1 wks) (1 wks) Duration of treatment and (time between treatments) Notes Cure in 64 ⁄ 114 (56%) Up to 6 versus 47 ⁄ 113 (42%) warts treatments Cure in 48 ⁄ 64 (75%) versus Up to 3 13 ⁄ 57 (23%) treatments Cure in 42 ⁄ 48 (88%) warts Up to 7 treatments Cure in 17 ⁄ 18 (94%) Up to 3 treatments Outcomes Injection Cure in 29 ⁄ 55 (52%) versus cryotherapy versus 26 ⁄ 60 (43%) Zinc sulfate versus placebo Zinc sulfate versus placebo Case series 115 adults Non-genital, mainly and children hand and foot warts 55 adults Multiple recalcitrant and children hand, foot, and facial warts 80 adults Recalcitrant trunk and children and extremity warts Clifton et al (40) Imm. Therapy Injections Johnson et al (37) Open Yaghoobi et al (36) Zinc Sulfate Al-Gurairi et al (35) Blinded Karabulut et al (32) Blinded Blinded ALA PDT ALA PDT versus placebo PDT ALA PDT versus placebo PDT ALA PDT Intervention Multiple recalcitrant Cimetidine common and foot warts 70 adults Multiple warts, Cimetidine and children all locations versus placebo 54 adults Recalcitrant Cimetidine and children non-genital warts versus placebo 34 children Case series Lu et al (28) Case series 31 adults Recalcitrant and children plantar warts 18 adults Facial flat warts Case series Schroeter et al (25) Cimetidine Orlow and Paller (30) Yilmez et al (31) 121 adults Recalcitrant hand and foot warts Plantar warts Wart description* Fabbrocini et al (27) Blinded Participants 45 adults Design Photodynamic Therapy Stender et al (26) Blinded Reference TABLE 1. Continued 220 Pediatric Dermatology Vol. 28 No. 3 May ⁄ June 2011 Case series Case series Case series Open Squaric Acid Lee (46) Micali et al (47) DCP Buckley et al (48) Choi et al (49) Open Case series Case control 50 children Podofilox Bunney et al (53) Retinoids Gelmetti et al (61) Kubeyinje (60) Recalcitrant, any location Flat warts Plantar warts Recalcitrant hand and foot warts Hand warts Plantar and periungual warts excluded *As per author report. Outcomes measured in number of patients unless otherwise specified. 20 children 382 adults and children 7 children Case series Cidofovir Field et al (54) 39 children Blinded 40 adults and teens SADBE Intervention Cure in 4 ⁄ 7 (57%) Cure in 19% versus 20% of warts Topical 0.05% tretinoin versus no treatment Oral etretinate Cure in 84% versus 32% Cure in 16 ⁄ 20 (80%) 6 weeks of daily application Up to 3 months Up to 12 weeks Up to 12 weeks 6 weeks Cure in 22 ⁄ 34 (65%) Up to 4 weekly versus 12 ⁄ 34 (35%) warts treaments Cure in 45 ⁄ 72 (63%) versus 38 ⁄ 75 (51%) Many patients received adjunctive therapies during study period One child dropped out of study Absolute numbers and treatment concentrations not provided One child dropped out due to irritation One child had detectable serum levels of 5-FU. Absolute numbers not reported for wart clearance Up to 22 treatments over 14 months Number of treatments Increased sustained not reported clearance with DCP Up to 10 weeks (twice weekly) Cure in 124 ⁄ 148 (84%) Cure in 42 ⁄ 45 (88%) Up to 15 treatments (2–4 wks) Duration of treatment and (time between treatments) Notes Cure in 20 ⁄ 29 (69%) Outcomes SA versus podophyllin Cure in 84% versus 81% Topical 1% cidofovir Injection with 5-FU + epinephrine + lidocaine Once daily versus twice daily topical 5% 5-FU DCP versus cryotherapy DCP Facial warts excluded, SADBE no genital warts treated Recalcitrant non-facial, non-genital warts Wart description* 60 adults Recalcitrant digital and children or plantar warts 83 patients, ages Location not reported not reported 188 children 29 adults and children Participants Gladsjo et al (50) 5-FU Yazdanfar et al (51) Blinded Design Reference TABLE 1. Continued Boull and Groth: Update: Treatment of Warts 221 222 Pediatric Dermatology Vol. 28 No. 3 May ⁄ June 2011 TABLE 2. Details of Referenced Review Articles Therapy Reference Trial types included No. of studies No. of studies adequate for reviewed analysis Design Salicylic acid Gibbs et al (6) Randomized 13 controlled Cryotherapy Gibbs et al (6) Randomized 16 controlled Cimetidine Fit and Open label and 21 Williams (33) randomized controlled Bleomycin Saitta et al (52) Any Interferon Gibbs et al (6) Randomized controlled 6 2 12 12 12 6 0 PHOTOTHERAPIES Laser Laser modalities abound, but carbon dioxide and pulsed dye lasers (PDL) are the most represented in the literature for wart treatment. Despite comparable resolution rates, CO2 laser is less favorable, producing nonselective thermal tissue destruction with wounds left to heal by secondary intension (16). Pulsed dye lasers is more selective, causing thermal damage directly to the microvasculature of the wart (16). In a trial by Robson et al (17), 40 adults were randomized to treatment with PDL or ‘‘conventional therapy’’ with cantharidin, cryotherapy, or both. Complete resolution was noted in 76% of recalcitrant and 51% of nonrecalcitrant warts treated with PDL and in 60% of recalcitrant warts and 77% of nonrecalcitrant warts treated with conventional therapy after up to four treatments. Differences were not statistically significant. Proximal lesions had better cure rates with PDL than acral lesions. Two additional series of PDL for recalcitrant warts in adults and children noted clearance rates of 63% to 89% (18,19). Vargas et al (20) reported good cosmetic results for PDL treatment of 12 adults with facial warts who all had complete clearing without scarring after a maximum of three sessions. Sethuraman et al (21) noted a clearance rate of 75% in 61 pediatric patients with recalcitrant warts after an average of 3.1 treatments. Complications included pigment changes, blistering, and mild scarring. Park et al (22) treated 56 children with PDL and achieved a complete response rate in 48.1% of warts (99 ⁄ 206) after a mean of 3.1 treatments. Park concluded that the higher cost of individual treatments may be balanced by the lower number of treatments needed to achieve remission. Outcomes Notes Cure in 144 ⁄ 191 (75%) versus 89 ⁄ 185 (48%) Cure in 11 ⁄ 31 (35%) versus 13 ⁄ 38 (34%) Cure in 48–81% in Controlled trials open studies; No could not be benefit of cimetidine pooled due to over placebo in variable controlled trials cimetidine dosing Any Cure in 0–94% Not a systematic review Interferon alpha, Cure ranged from Studies could beta, or gamma 22% to 66% in not be compiled versus placebo the interferon groups Salicylic acid versus placebo Cryotherapy versus placebo Various designs Pretreatment with salicylic acid may make PDL more cost-effective by decreasing the number of laser treatments required for cure. A study of 19 patients randomized to PDL therapy with or without salicylic acid pretreatment found no significant difference in cure rates after five treatments (69.7% in the SA-treated group vs 66.6% in the control group), but the group pretreated with salicylic acid required an average of 2.2 treatments compared to 3.1 treatments in the control group (p < 0.05) (23). Pulsed dye lasers is an important new therapy that is safe and generally well tolerated by children. Cooling devices can lessen pain. Photodynamic Therapy In photodynamic therapy (PDT), a photosensitizing agent, most commonly 5-aminolaevulinic acid (ALA), is topically applied and absorbed by hyperkeratotic wart keratinocytes. When stimulated by light, accumulated porphyrins induce a photooxidation cascade damaging treated cells (24). A series of 31 children and adults with recalcitrant plantar warts treated with ALA-PDT attained a clearance rate of 88% (42 ⁄ 48) of warts after an average of 2.3 treatments. Younger patients had better outcomes, with 100% clearance in all patients younger than 27 and no clearance in patients older than 45. Side effects included minor pain and itching with one case of mild hypopigmentation (25). In a randomized controlled study, 45 adults with recalcitrant hand and foot warts were treated with either ALA-PDT or placebo-PDT with weekly treatments for up to 6 weeks. Complete clearance of warts was seen in 56% of patients in the active treatment group, compared Boull and Groth: Update: Treatment of Warts with 42% in the placebo group (p < 0.05) (26). In a similar study of ALA-PDT for plantar warts, 121 adults were randomized to treatment with either ALA-PDT or placebo-PDT. After up to three treatments, a cure rate of 75% (48 ⁄ 64) was noted in the ALA-PDT group compared to 22.8% (13 ⁄ 57) in the placebo group (p < 0.001) (27). Like PDL, PDT gives good cosmetic results for facial warts. Eighteen adults treated with azone followed by ALA-PDT had a clearance rate of 94.4% after two sessions. Twelve patients had transient pigment changes, but no scarring resulted (28). IMMUNOTHERAPIES Cimetidine Oral cimetidine, a histamine H2-receptor antagonist was trialed as a therapy for warts due to its immunomodulatory effects (29). An initial case series of 34 children treated with cimetidine dosing of 25 to 40 mg ⁄ kg ⁄ day by Orlow et al (30) demonstrated promising results with an 81% (26 ⁄ 32) cure rate over 2 months. More rigorous studies failed to show the same benefit. Two doubleblinded placebo-controlled studies in adults and children showed no significant benefit of cimetidine over placebo (31,32). Despite case reports and smaller open-label studies with higher success rates in children, a 2007 review notes that no high-quality evidence exists to support the use of cimetidine for warts (33). Any benefit may lie more in the psychological aspect of treatment. Zinc A promising new therapy, zinc, acts as an immune modulator. Deficiency results in lymphopenia and treatment of cell cultures with zinc produce polyclonal activation of lymphocytes (34). In a randomized controlled study, 80 children and adults with recalcitrant warts were treated with placebo or oral zinc sulfate (10 mg ⁄ kg up to a maximum dose of 600 mg ⁄ day) for 2 months (35). Of those that completed the study, 86.9% (20 ⁄ 23) of patients in the zinc-treated group compared to 0% (0 ⁄ 20) of patients in the placebo group (p < 0.001) had complete wart clearance. Importantly, all participants were zinc deficient prior to the study, and treatment response correlated with increase in serum zinc levels. The authors postulated that zinc-deficient individuals may be more prone to developing warts, as a series of healthy controls had normal zinc levels. Results are impressive, but the large drop-out rate may have impacted outcomes. Adverse events in the 223 zinc-treated group included nausea (100%), vomiting (12.7%), and mild epigastric pain (13%). In 55 children and adults with recalcitrant warts, 78% of patients randomized to treatment with zinc had complete wart resolution in 2 months compared with 13% of patients treated with placebo. No adverse reactions were reported. Again, a large number (68%) of patients had low serum zinc levels prior to treatment (36). Initial studies suggest that oral zinc sulfate is an effective, inexpensive, and painless way to treat warts. Additional placebo-controlled studies in zinc-replete patients are needed to determine true therapeutic benefit. Injected Immunotherapies The use of injections of immune-stimulating antigens has grown, buoyed by studies showing not only regression of the injected wart, but also resolution of distant warts. In a trial by Johnson et al (37), 115 patients aged 5 to 72 were treated with cryotherapy or wart injection with Candida or mumps antigen. No significant difference was shown between cure rates in the two groups after three treatments, but 14 of 18 of cured antigen-treated patients (78%; 95% confidence interval: 52–94%) experienced clearing of all other warts despite receiving antigen injections into only the largest wart. The same investigators then randomized 233 adults and children to intralesional injection with one of four treatments: mumps, Candida, or trichophyton antigen; antigen plus interferon alfa 2b; alfa 2b alone; or placebo (saline). After up to five treatments, the groups treated with antigen alone or antigen with interferon had a clearance rate of 56% compared to 23% in the groups treated with placebo or interferon alone (p < 0.001). Distant warts showed improved resolution in patients receiving antigen (49%) compared to patients treated with interferon or saline alone (16%) (p < 0.001). Interferon alfa-2b did not afford a significant benefit alone or in combination with antigen (38). A newer trial using MMR vaccine intralesional injections in 23 adults with plantar warts showed complete resolution in 87% of patients after up to three treatments (39). The study, however, was flawed by a high drop-out rate and lack of a control group. In a pediatric series of 47 children with multiple recalcitrant warts treated with intralesional mumps or Candida injections, 47% of patients were cured after an average of 3.78 treatments. Fourteen children noted resolution of distant nontreated warts. Patients reported itching at the injection site as the primary side-effect (40). Other complications of immunotherapy injections have included cases of fever and myalgias treated successfully with NSAIDs, and a single case report of a 224 Pediatric Dermatology Vol. 28 No. 3 May ⁄ June 2011 painful purple finger following a subungual wart injection. Symptoms self resolved (41). Needles provoke anxiety in many children, and injections into the soles of the feet are particularly painful. Care must be taken to ensure proper restraint of the child prior to the procedure to protect both patient and physician from accidental needle punctures. Topical application of ice packs prior to injection may minimize pain. Interferon In his review of cutaneous wart therapies, Dr. Gibbs examined six trials testing the efficacy of intralesional interferon injections (6). Two of these studies included children and noted cure rates from 30% to 66%. Gibbs noted that the quality of these studies was low, and that interferon does not appear to be effective. Diphencyprone is more stable in solution and less expensive than SADBE. Buckley et al (48) documented a 75% clearance rate in 48 children and adults treated with DCP. Fifty-six percent of patients, however, experienced adverse events including blistering, generalized eczematous eruptions, influenza-like symptoms, and inguinal lymphadenopathy. A randomized controlled study of 147 patients found no significant benefit of DCP over cryotherapy for wart resolution, but noted increased sustained clearance as 93.3% of patients with complete resolution treated with DCP versus 76.3% treated with cryotherapy maintained clearance at 12 months (p < 0.05) (49). ANTIMITOTIC THERAPIES 5-FU Trials of imiquimod as a treatment for genital warts propose that it acts as an immune response modifier, stimulating the production of interferon alpha and cytokines (42). A case series of 50 children and adults with refractory warts treated nightly with application of 5% imiquimod cream on five nights per week over an average of 9.2 weeks noted a complete clearance rate of 30% (15 ⁄ 50) (43). Warts located on the trunk and face had higher response rates than warts on the feet. However, 18 children with mainly acral recalcitrant warts treated with twice daily 5% imiquimod cream and intermittent wart paring for an average of 5.8 months had a higher clearance rate of 88.9% (16 ⁄ 18) (44). In a trial of imiquimod for recalcitrant sub and periungual warts, 15 adults and children were pretreated with a salicylic acid preparation followed with imiquimod 5% cream under an occlusive dressing five nights per week for up to 16 weeks (45). Eighty percent of patients had total clearance of their warts. Local erythema, pruritis, and burning sensation were noted. Imiquimod is well suited to use in children and has the benefit of home use. 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU), a chemotherapeutic agent, is thought to cause wart resolution by interfering with the synthesis of DNA and RNA in infected cells (50). To investigate both efficacy and systemic effects of topical 5-FU in the pediatric population, Gladsjo et al (50) randomized 39 children to treatment with either once or twice daily application of 5% 5-FU cream plus daily filing, soaking, and occlusion with duct tape. After 6 weeks of treatment, 19% of the once daily and 20% of the twice daily treated warts demonstrated complete resolution (no significant difference). One child out of 39 had a detectable serum 5-FU level at the end of treatment and had been in the once-a-day treatment group. Complications included erythema, ulceration, crusting, and occasional hypopigmentation. A 2008 study of 40 adults and teens treated with either once weekly intralesional injection of 5-FU mixed with epinephrine and lidocaine or saline for up to 4 weeks showed complete resolution of 65% (22 ⁄ 34) of 5-FU injected warts compared to 35.3% (12 ⁄ 34) of saline injected warts (p £ 0.05) (51). Authors note that due to the low doses of 5-FU injected, systemic reactions were eliminated, but serum levels of 5-FU were not documented. This therapy needs more investigation before its use in children can be advised. Squaric Acid and Diphencyprone Bleomycin Both squaric acid dibutylester (SADBE) and diphencyprone (DCP) act to induce a type IV hypersensitivity reaction against the contact agent bound to human or viral proteins (46). Two series of 29 and 188 mostly pediatric patients sensitized and then treated with SADBE applications demonstrated 69% and 84% clearance rates, respectively (46,47). Bleomycin, another chemotherapeutic agent, prevents mitosis of HPV-infected (human papillomavirus-infected) cells by inducing cleavage of the DNA backbone (52). A recent review article, examining 12 studies of wart treatment with intralesional bleomycin, published between 1976 and 2002 noted cure rates from 0% to 94% (52). The highest quality data was derived from a Imiquimod Boull and Groth: Update: Treatment of Warts double-blinded placebo-controlled study of 24 adults and teens with 59 matched pairs of hand warts. Patients received 0.1% bleomycin injections into one of their paired warts and saline injections into the matched control wart for up to three injections. Bleomycininjected warts showed a cure rate of 58% (34 ⁄ 59) compared to 10% (6 ⁄ 59) in the placebo group after 6 weeks (p < 0.001). All subjects with remaining warts received an additional injection with bleomycin, after which the cure rate for bleomycin-treated warts was 76% (53). Bleomycin injections typically induce eschar formation and inflammation. Complications have included pain with injection, urticaria, nail loss, hyperpigmentation, and very rarely Raynaud’s phenomenon. Pulmonary fibrosis is an adverse reaction seen in systemic use, but not reported in intralesional use. As safety of intralesional bleomycin has not been studied in the pediatric population, and because it is quite painful, we do not recommend bleomycin for young children. 225 Cidofovir A virucidal agent that prevents DNA synthesis, cidofovir is most commonly used intravenously to treat cytomegalovirus retinitis in immunocompromised patients. Small studies indicate benefit in the treatment of refractory cutaneous warts. In a series of seven pediatric patients with hand and foot warts treated with topical 1% cidofovir, four patients had complete clearance (54). Treatments were nightly for up to 12 weeks, and one child stopped treatment due to local irritation. Of the two immunocompromised children in the study, one cleared and one did not. Two children with refractory leg or plantar warts (55) and a 9-year-old girl with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and refractory plantar warts (56) were treated successfully with topical cidofovir. An 11-year-old girl with hereditary congenital lymphadema and highly refractory All Patients Pediatric Wart Treatment Algorithm Topical SA* Refusal of Painful Treatments? No‡ Yes Watchful waiting Zinc sulfate Cimetidine Topical retinoid Imiquimod Many Warts? No Yes ImmunoCompromised? Facial?† No No Yes Yes Flat Warts? Highly Keratotic? Yes 40% SA to debulk Flat Warts? No No No Periungual? No Cryo Cantharone Plusφ Injected Im Txψ Imiquimod 5-FU PDL SADBE/DCP Bleomycinαβ Cryo Cantharidin PDL/PDT EDα Yes Topical retinoid Imiquimod PDL/PDT Injected Im Txψ Cantharone Plusφ Cryo 5-FU PDL Yes Cryo 5-FU Cidofovir Injected Im Txψ Topical retinoid Cryo Yes Cryo Imiquimod PDL Injected Im Txψ Figure 1. Pediatric wart treatment algorithm. SA, salicylic acid; Cryo, cryotherapy; Injected Im Tx, injected immunotherapy; 5-FU, 5-Fluorouracil; PDL, pulsed dye laser; PDT, photodynamic therapy; ED, electrodesiccation; SADBE, squaric acid dibutylester; DCP, diphencyprone. *Topical salicylic acid should always be used with soaking and filing; àZinc sulfate or cimetidine may be added to all other treatments in this category; Increased delicacy must be used for all treatments on the face; wInjected immunotherapies include MMR, trichophyton, and Candida; aBleomycin and electrodesiccation should only be used in older patients with high motivation for treatment; bBleomycin should not be used on digits due to risk of necrosis; /Contains salicylic acid 30%, podophyllin 2%, and cantharidin 1%. 226 Pediatric Dermatology Vol. 28 No. 3 May ⁄ June 2011 facial, hand, and foot warts had resolution of more than 90% of her lesions after five treatments with IV cidofovir (57). Adverse effects of IV administration include nephrotoxicity and neutropenia. One case of acute renal failure has been reported in an adult being treated with topical 4% cidofovir, but confounding factors likely played a role (58). Larger studies are needed to further assess safety and efficacy in children. Podophyllin Resin and Podophyllotoxin Podophyllin resin, an extract of the mayapple plant, contains the active ingredient podophyllotoxin, an antimitotic agent. Podophyllotoxin has been used most successfully to treat anogenital warts, but also shows benefit in the treatment of cutaneous warts. Bunney et al (59) found podophyllin to be equivalent to treatment with salicylic acid for plantar warts in 382 adults and children. As podophyllin has been associated with neurotoxicity, and as the concentration of the active ingredient varies between batches, the use of podophyllotoxin is now preferred. Sinecatechins Sinecatechins, green tea extracts, have shown promising results for the topical treatment of anogenital warts, but have not been tested systematically in cutaneous warts or in children. The mechanism of action is not well defined. Retinoids Both topical and oral retinoids treat warts by influencing keratinization and cellular proliferation. In a casecontrol trial of 50 pediatric patients, those treated with daily application of 0.05% tretinoin cream showed an 85% clearance rate of warts compared to a 32% clearance in controls (60). This modality seems well suited for painless treatment of facial planar warts. Treatment of 20 children with oral etretinate for up to 3 months produced complete and sustained wart clearance in 16 children (61). Due to the strict precautions that must be taken when using oral retinoids in adolescent girls, and minimal data to support its efficacy, we do not recommend etretinate for treatment of warts. Pain Management Evaluation of the benefit of eutectic mixture of local anesthetics cream (EMLA) prior to cryotherapy, with a randomized placebo controlled trial in adults and children showed no significant improvement in the pain experienced during the procedure. In subgroup analysis, however, decreased pain was seen in children receiving cryotherapy to the soles or palms (62). While specific guidelines are lacking, pain control certainly makes treatments more tolerable for the patient, parent, and physician. Icepacks applied 5 minutes before wart injections can help to numb the site. Nerve blocks should be considered prior to treatment of larger, localized wart clusters. Eutectic mixture of local anesthetics cream is a useful pain-mitigating tool when placed prior to laser therapies and nerve block injections. For maximal effect, EMLA should be applied 1 hour prior to the procedure under an occlusive dressing. Other topical anesthetic preparations, such as liposomal lidocaine, may be used similarly. Special Pediatric Considerations In our experience, good parent-provider communication is the most important element in effectively treating pediatric patients. Prior to the implementation of any of the above-described treatments, parents’ questions and concerns must be fully addressed. In some cases, an initial pain-free visit to discuss wart etiology and treatment options and to establish a rapport with the child can ease anxiety. Therapies and complications should be described in language that both the parent and child can understand. Instruction handouts are useful to ensure proper technique of home therapies. A child-friendly office can make for a more positive experience. Music or movies in treatment rooms provide a helpful distraction for children. Talking the child through procedures by providing reassurance and calmly explaining what to expect next is essential. Summary and Recommendations Providers face an overwhelming number of treatment options for the management of cutaneous warts. We have included a treatment algorithm based on the combination of our clinical experience and the evidence available (Fig. 1). As the only therapy thoroughly tested and proven effective is salicylic acid, we recommend starting with this in all patients with nonfacial warts. Parents must be specifically instructed in its proper use, including the importance of soaking and filing lesions between applications. For warts that fail to respond to salicylic acid, the practitioner must determine what intensity of therapy is appropriate. Patient age and maturity level as well as parent preference must be considered. In most cases, another destructive method should be employed. Cryotherapy for nonfacial warts, cantharidin, and Cantharone Plus are all good options and are readily Boull and Groth: Update: Treatment of Warts available at most primary care offices. For parents or patients who refuse painful therapies, ongoing use of salicylic acid or addition of a topical retinoid or imiquimod 5% in conjunction with oral zinc sulfate or cimetidine is recommended. If after multiple failed treatment attempts warts are still present, if warts are located on the face, or if the number of warts is extensive, referral to a dermatologist is warranted. Immunocompromised patients should be referred sooner, as their lesions tend to be more refractory. The dermatologist may opt to repeat simple destructive methods in a more aggressive manner prior to moving on to other options. Next-line treatments include injected immunotherapies (MMR, trichophyton, Candida), topical immunotherapies (SADBE, DCP), topical 5-FU, pulsed dye laser, and photodynamic therapy. As not all dermatology offices are equipped to perform all procedures, the referring provider should be familiar with the resources available in his or her area. In older, highly motivated patients with warts refractory to all other methods, the use of bleomycin, or electrodesiccation may be considered. Concluding Remarks Looking to the future of wart therapies, immune modulation seems to hold growing promise. One of the greatest breakthroughs in the treatment of HPV has been the quadivalent vaccine. Although it has been tested only for prevention against subtypes responsible for cervical cancer and anogenital warts, it may provide a broader effect. A newly published case report documents the clearance of 30 refractory cutaneous warts in a 31-yearold male after treatment with the HPV vaccine (63). The author proposes a cross-protective effect that has been previously described in the HPV vaccine literature. As children become routinely vaccinated with the HPV vaccine, it will be informative to follow cutaneous wart rates. The lack of a universally effective wart therapy has continued to drive the search for new cures; however, without accurate appraisal of older modalities, it is difficult to gage the success and cost-effectiveness of the new and more expensive treatments. The EVERT trial, currently in progress, is a randomized controlled study comparing wart treatment with liquid nitrogen and salicylic acid in adults and children (64). Hopefully, additional high quality clinical investigations of our more widely used modalities will follow. For the time being, we must thoughtfully apply the data available to provide safe and effective care to our patients with warts. 227 REFERENCES 1. Van Haalen FM, Bruggink SC, Gussekloo J et al. Warts in primary schoolchildren: prevalence and relation with environmental factors. Br J Dermatol 2009;181:148– 152. 2. Keefe M, Dick DC. Dermatologists should not be concerned in routine treatment of warts. Br Med J 1988;296:177–179. 3. Messing AM, Epstein WL. Natural history of warts: a 2-year study. Arch Dermatol 1963;87:306–310. 4. Ciconte A, Campbell J, Tabrizi S et al. Warts are not merely blemishes on the skin: a study on the morbidity associated with having viral cutaneous warts. Australas J Dermatol 2003;44:169–173. 5. Torrelo A. What’s new in the treatment of viral warts in children. Pediatr Dermatol 2002;19:191–199. 6. Gibbs S, Harvey I, Sterling JC et al. Local treatments for cutaneous warts: systematic review. Br Med J 2002;325: 461–468. 7. Gibbs S, Harvey I. Topical treatments for cutaneous warts. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006; Issue 3. Art. No.: CD001781. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD 001781.pub2. 8. Moed L, Shwayder TA, Chang MW. Cantharidin revisited: a blistering defense of an ancient medicine. Arch Dermatol 2001;137:1357–1360. 9. Kartal Durmazlar SP, Atacan D, Eskioglu F. Cantharidin treatment for recalcitrant facial flat warts: a preliminary study. J Dermatolog Treat 2009;20:114–119. 10. de Bengoa Vallejo RB, Iglesias MEL, Gómez-Martı́n B et al. Application of cantharidin and podophyllotoxin for the treatment of plantar warts. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 2008;98:445–450. 11. Focht D, Spicer C, Fairchok M. The efficacy of duct tape vs cryotherapy in the treatment of verruca vulgaris (the common wart). Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2002;156:971– 974. 12. de Haen M, Spigt M, van Uden CJT et al. Efficacy of duct tape vs placebo in the treatment of verruca vulgaris (warts) in primary school children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2006;160:1121–1125. 13. Wenner R, Askari SK, Cham PMH et al. Duct tape for the treatment of common warts in adults: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Arch Dermatol 2007;143:309– 313. 14. Ahmed I, Agarwal S, Ilchyshyn A et al. Liquid nitrogen cryotherapy of common warts: cryo-spray vs cotton wool bud. Br J Dermatol 2001;144:1006–1009. 15. Connolly M, Bazmi K, O’Connell M et al. Cryotherapy of viral warts: a sustained 10-s freeze is more effective than the traditional method. Br J Dermatol 2001;145:554–557. 16. Tosti A, Piraccini BM. Warts of the nail unit: surgical and nonsurgical approaches. Dermatol Surg 2001;27:235– 239. 17. Robson KJ, Cunningham NM, Kruzan KL et al. Pulseddye laser versus conventional therapy in the treatment of warts: a prospective randomized trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000;43:275–280. 18. Kopera D. Dermatologic surgery verrucae vulgares: flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye laser treatment in 134 patients. Int J Dermatol 2003;42:905–908. 228 Pediatric Dermatology Vol. 28 No. 3 May ⁄ June 2011 19. Schellhaas U, Gerber W, Hammes S et al. Pulsed dye laser treatment is effective in the treatment of recalcitrant viral warts. Dermatol Surg 2008;34:67–72. 20. Vargas H, Hove C, Dupree M et al. The treatment of facial verrucae with the pulsed dye laser. Laryngoscope 2002;112: 1573–1576. 21. Sethuraman G, Richards K, Hiremagalore R et al. Effectiveness of pulsed dye laser in the treatment of recalcitrant warts in children. Dermatol Surg 2010;36:58– 65. 22. Park HS, Kim JW, Jang SJ et al. Pulsed dye laser therapy for pediatric warts. Pediatr Dermatol 2007;24:177–181. 23. Akarsu S, Ilknur T, Demirtaşoglu M et al. Verruca vulgaris: pulsed dye laser therapy compared with salicylic acid + pulsed dye laser therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2006;20:936–940. 24. Lipke MM. An armamentarium of wart treatments. Clin Med Res 2006;4:273–293. 25. Schroeter CA, Pleunis J, van Nispen tot Pannerden C et al. Photodynamic therapy: new treatment for therapyresistant plantar warts. Dermatol Surg 2005;31:71–75. 26. Stender IM, Na R, Fogh H et al. Photodynamic therapy with 5-aminolaevulinic acid or placebo for recalcitrant foot and hand warts: a randomized double-blind trial. Lancet 2000;355:963–966. 27. Fabbrocini G, Di Costanzo MP, Riccardo AM et al. Photodynamic therapy with topical d-aminolaevulinic acid for the treatment of plantar warts. J Photochem Photobiol B 2001;61:30–34. 28. Lu Y, Wu J, He Y et al. Efficacy of topical aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy for the treatment of verruca planae. Photomed Laser Surg 2010;28:561–563. 29. Jin Z, Kumar A, Cleveland RP et al. Inhibition of suppressor cell function by cimetidine in a murine model. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 1986;38:350–356. 30. Orlow S, Paller A. Cimetidine therapy for multiple viral warts in children. J Am Acad Dermatol 1993;28: 794–796. 31. Yilmaz E, Alpsoy E, Basaran E. Cimetidine therapy for warts: a placebo-controlled, double-blind study. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996;34:1005–1007. 32. Karabulut AA, Sahin S, Eksioglu M. Is cimetidine effective for nongenital warts: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arch Dermatol 1997;133:533–534. 33. Fit KE, Williams PC. Use of histamine2-antagonists for the treatment of verruca vulgaris. Ann Pharmacother 2007;41:1222–1226. 34. Wirth JJ, Fraker PJ, Kierszenbaum F. Zinc requirement for macrophage function; effect of zinc deficiency on uptake and killing of protozoan parasites. Immunology 1989;68:114–119. 35. Al-Gurairi FT, Al-Waiz M, Sharquie KE. Oral zinc sulfate in the treatment of recalcitrant viral warts: randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. Br J Dermatol 2002;146: 423–431. 36. Yaghoobi R, Sadighha A, Baktash D. Evaluation of oral zinc sulfate effect on recalcitrant multiple viral warts: a randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009;60:706–708. 37. Johnson SM, Roberson PK, Horn TD. Intralesional injection of mumps or Candida skin test antigens—a novel immunotherapy for warts. Arch Dermatol 2001;137:451– 455. 38. Horn TD, Johnson SM, Helm RM et al. Intralesional immunotherapy of warts with mumps, Candida, and Trichophyton skin test antigens—a single-blinded, randomized, and controlled trial. Arch Dermatol 2005;141: 589–594. 39. Gamil H, Elgharib I, Nofal A et al. Intralesional immunotherapy of plantar warts: report of a new antigen combination. J Am Acad Dermatol 2010;63:40–43. 40. Clifton MM, Johnson SM, Roberson PK et al. Immunotherapy for recalcitrant warts in children using intralesional mumps or Candida antigens. Pediatr Dermatol 2003;20: 268–271. 41. Peman M, Sterling JB, Gaspari A. The painful purple digit: an alarming complication of Candida albicans antigen treatment for recalcitrant warts. Dermatitis 2005;16:38–40. 42. Garland SM, Sellors JW, Wikstrom A et al. Imiquimod 5% cream is a safe and effective self-applied treatment for anogenital warts. Results of an open-label, multicentre Phase IIIB trial. Int J STD AIDS 2001;12:722–729. 43. Hengge UR, Esser S, Schultewolter T et al. Self-administered topical 5% imiquimod for the treatment of common warts and molluscum contagiosum. Br J Dermatol 2000;143:1026–1031. 44. Grussendorf-Conen EI, Jacobs S. Efficacy of imiquimod 5% cream in the treatment of recalcitrant warts in children. Pediatr Dermatol 2002;19:263–266. 45. Micali G, Dall’Oglio F, Nasca MR. An open label evaluation of the efficacy of imiquimod 5% cream in the treatment of recalcitrant subungual and periungual cutaneous warts. J Dermatolog Treat 2003;14:233–236. 46. Lee A, Mallory SB. Contact immunotherapy with squaric acid dibutylester for the treatment of recalcitrant warts. J Am Acad Dermatol 1999;41:595–599. 47. Micali G, Nasca MR, Tedeschi A et al. Use of squaric acid dibutylester (SADBE) for cutaneous warts in children. Pediatr Dermatol 2000;17:315–318. 48. Buckley DA, Keane FM, Munn SE et al. Recalcitrant viral warts treated by diphencyprone immunotherapy. Br J Dermatol 1999;141:292–296. 49. Choi M, Seo SH, Kim IH et al. Comparative study on the sustained efficacy of diphencyprone immunotherapy versus cryotherapy in viral warts. Pediatr Dermatol 2008;25: 398–399. 50. Gladsjo JA, Alió Sáenz AB, Bergman J et al. 5% 5fluorouracil cream for treatment of verruca vulgaris in children. Pediatr Dermatol 2009;26:279–285. 51. Yazdanfar A, Farshchian M, Fereydoonnejad M et al. Treatment of common warts with an intralesional mixture of 5-fluorouracil, lidocaine, and epinephrine: a prospective placebo-controlled, double-blind randomized trial. Dermatol Surg 2008;34:656–659. 52. Saitta P, Krishnamurthy K, Brown LH. Bleomycin in dermatology: a review of intralesional applications. Dermatol Surg 2008;34:1299–1313. 53. Bunney MH, Nolan MW, Buxton PK et al. The treatment of resistant warts with intralesional bleomycin: a controlled clinical trial. Br J Dermatol 1984;111:197–207. 54. Field S, Irvine AD, Kirby B. The treatment of viral warts with topical cidofovir 1%: our experience of seven pediatric patients. Br J Dermatol 2009;160:223–224. 55. Zabawski EJ Jr, Sands B, Goetz D et al. Treatment of verruca vulgaris with topical cidofovir. JAMA 1997; 278:1236. Boull and Groth: Update: Treatment of Warts 56. Tobin AM, Cotter M, Irvine AD et al. Successful treatment of a refractory verruca in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia with topical cidofovir. Br J Dermatol 2005;152:386–388. 57. Cusack C, Fitzgerald D, Clayton TM et al. Successful treatment of florid cutaneous warts with intravenous cidofovir in an 11-year-old girl. Pediatr Dermatol 2008;25: 387–389. 58. Bienvenu B, Martinez F, Devergie A et al. Topical use of cidofovir induced acute renal failure. Transplantation 2002;73:661–662. 59. Bunney MH, Nolan MW, Williams DA. An assessment of methods of treating viral warts by comparative treatment trials based on a standard design. Br J Dermatol 1976;94: 667–669. 60. Kubeyinje EP. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of 0.05% tretinoin cream in the treatment of plane warts in Arab children. J Dermatol Treat 1996;7:21– 22. 229 61. Gelmetti C, Cerri D, Schiuma AA et al. Treatment of extensive warts with etretinate; a clinical trial in 20 children. Pediatr Dermatol 1987;4:254–258. 62. Gupta AK, Koren G, Shear NH. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of eutectic lidocaine ⁄ prilocaine cream 5% (EMLA) for analgesia prior to cryotherapy of warts in children and adults. Pediatr Dermatol 1998;15:129–133. 63. Venugopal SS, Murrell DF. Recalcitrant cutaneous warts treated with recombinant quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (Types 6, 11, 16, and 18) in a developmentally delayed, 31-year-old white man. Arch Dermatol 2010;146: 475–477. 64. Cockayne ES. The EVERT (effective verruca treatments) trial protocol: a randomised controlled trial to evaluate cryotherapy versus salicylic acid for the treatment of verrucae. Trials 2010;11:12.

© Copyright 2025