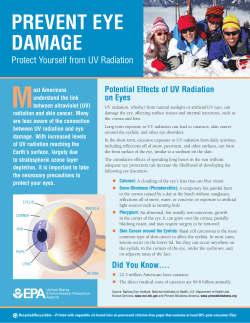

United States Office of Radiation and EPA 402-B-00-001 August 2000