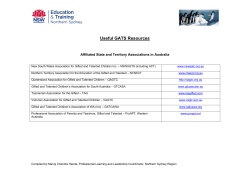

ted Gif G d