Child Adjustment and Parent Efficacy Scale (CAPES): a Parent Report Measure

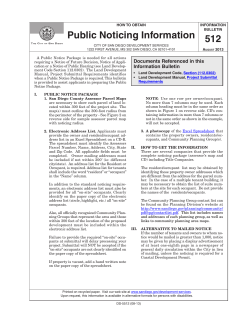

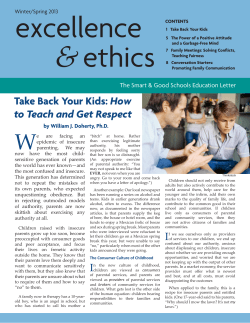

Australian Psychologist (Accepted 19/2/14). 1 Child Adjustment and Parent Efficacy Scale (CAPES): Development and Initial Validation of a Parent Report Measure Alina Morawska* Matthew R Sanders, Divna Haslam Ania Filus Renee Fletcher Parenting and Family Support Centre, School of Psychology, The University of Queensland Brisbane, Australia *Corresponding author Parenting and Family Support Centre School of Psychology University of Queensland Brisbane 4072 Ph: +61 7 3365 7304 Fax: +61 7 3365 6724 Email: alina@psy.uq.edu.au Abstract Background: This study examined the psychometric characteristics of the Child Adjustment and Parental Efficacy Scale (CAPES). The CAPES was designed as a brief outcome measure in the evaluation of both public health and individual or group parenting interventions. The scale consists of a 30-item Intensity scale with two subscales measuring children’s behaviour problems and emotional maladjustment and a 20-item Self-efficacy scale which measures parent’s self-efficacy in managing specific child problem behaviours. Method: A sample of 347 parents of 2-12 year old children participated in the study. Results: Psychometric evaluation of the CAPES revealed that both the Intensity and Self-efficacy scales had good internal consistency, as well as satisfactory convergent and discriminant validity. Conclusions: Potential uses of the measure and implications for future validation studies are discussed. What is already known about this topic: Child behavioural and emotional problems are common and there are a range of effective intervention approaches. Population level tools for assessment of child behavioural and emotional problems are needed. Existing tools have a number of limitations and weaknesses in application across clinical and population levels. What this topic adds: This study reports on the development and piloting of the Child Adjustment and Parent Efficacy Scale (CAPES). The CAPES shows good psychometric properties, and therefore has the potential to be used as a measure of child behavioural and emotional problems and parenting efficacy across a range of contexts. Further research is needed to establish population norms, and generalizability across groups and cultures. 1 Australian Psychologist (Accepted 19/2/14). 2 The key to healthy optimal child development begins with positive, nurturing, and responsive parent-child relationships (Collins, Maccoby, Steinberg, Hetherington, & Bornstein, 2000; Vimpani, Patton, & Hayes, 2002). Traditionally, parenting programs that foster the development of such relationships by increasing the knowledge, skills and confidence of parents have been conducted within clinical settings targeting at-risk families or those identified with more severe child behavioural difficulties (e.g., Sanders, Markie-Dadds, Tully, & Bor, 2000; Webster-Stratton & Reid, 2003). However, the need for wide reaching, evidence-based parenting support is gaining increasing highlevel international recognition (e.g., Biglan, Flay, Embry, & Sandler, 2012; Sanders, 2012). To inform public health policy and parenting interventions child adjustment measures that fulfil specific requirements need to be developed. Such measures should have good psychometric properties, be reliable, change sensitive, readily deployable, and be able to facilitate the tracking of intervention outcomes at both individual and population levels. While a number of well validated measures of child behaviour and adjustment exist, these suffer from a number of limitations when applied in the context of a public health approach to parenting intervention. These limitations include: (a) a focus on clinical diagnosis (e.g., Conners, 2009) and limited examination of frequent, but problematic behaviours seen among children with subclinical problems (Goodman, 1997); (b) in addition, most measures focus on older children with limited screening tools available for children under age 5 (Bagner, Rodríguez, Blake, Linares, & Carter, 2012; Briggs-Gowan et al., 2013). Furthermore, most measures: (c) take a deficit approach and do not examine behavioural competencies (Tsang, Wong, & Lo, 2012); (d) a focus on only one type of behaviour (e.g., Kovacs, 2010) or only on internalizing (e.g., Spence, 1998) or externalizing (e.g., Eyberg & Pincus, 1999) behaviour. The other problematic issues with the existing measures include: (e) low to moderate estimates of internal consistency (e.g., Strenghts and Diffiuclites Questionnaires .51-.76; Smedje, Broman, Hetta, & von Knorring, 1999); (f) measures such as the CBCL (Achenbach, 2000) that are lengthy and time consuming for parents to complete (Goodman & Scott, 1999), and; (g) licensing fees, which can place limits on dissemination in large population studies (e.g., Eyberg & Pincus, 1999; Goodman, 1997). In particular, the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire which is a widely used screening tool, suffers from a number of limitations for population level use, such as relatively low internal consistency (Goodman, 2001) particularly for some subscales (e.g., peer problems subscale), limited data for children younger than seven years (Mieloo et al., 2012), questions about the underlying structural validity (Palmieri & Smith, 2007), limited data on sensitivity to change (Tsang et al., 2012), as well as the requirement of a licence fee for online administration. Furthermore, in the context of parenting and parenting intervention, parental self-efficacy is increasingly being recognised as important to understanding the ways in which parent-child relationships and child behavioural and emotional problems develop and maintain over time (Jones & Prinz, 2005) and none of the existing measures include parental self-efficacy in relation to the specific behavioural and emotional problems measured. The term “self-efficacy”, often used interchangeably with “confidence”, is defined as “the conviction that one can successfully execute the behaviour required to produce the outcomes” (Bandura, 1977). Although “confidence” refers to the strength of a particular belief, the construct of self-efficacy, as defined by Bandura, specifically pertains to an individual’s belief that they can perform a given activity successfully, as well as to the strength of that belief (Bandura, 1997). Thus, self-efficacy beliefs are attached to specific domains of functioning (e.g. parenting) (Bandura, 2000). Parental self-efficacy has been shown to impact on children’s behaviour both directly and indirectly via parenting practices, and on parental adjustment (Jones & Prinz, 2005). Furthermore, it has been identified as an important modifiable factor for parenting intervention (Morawska & Sanders, 2007) alongside parental competence (Jones & Prinz, 2005). While there are a number of parental efficacy measures, these are generally measures of global self-efficacy (e.g., Johnston & Mash, 1989), despite the fact that task specific efficacy is a better predictor of child outcomes (Jones & Prinz, 2005). Similarly, while task-specific measures do exist (e.g., Sanders & Woolley, 2005) these are not integrated with existing measures of child behavioural problems, thus increasing the assessment burden on families when both variables are assessed. Furthermore, there may be differences between a parent’s perceptions of their child’s behaviour and their own self-efficacy in dealing with the behaviour which can be important to differentiate in an intervention approach. For example, the 2 Australian Psychologist (Accepted 19/2/14). 3 parent who experiences relatively low levels of behaviour problems, but nevertheless has low selfefficacy about managing these might need quite a different treatment approach to one who experiences high levels of behaviour problems and has high self-efficacy. The current study provides initial validation of a newly developed measure of child behavioural and emotional adjustment that would overcome some of the limitations outlined above, enabling population level assessment of child adjustment, and facilitating outcome evaluation and meta-analysis of population-level interventions. In developing the assessment tool we sought to create a measure that would meet a number of different criteria. Specifically, the measure needed to be easy to administer, score, and interpret, use consistent methods of scaling, and have sound psychometric properties in terms of reliability, face and construct validity. In addition, we sought to develop a measure that would have the following characteristics: (a) minimal assessment burden, (b) be sensitive to change in both clinical and non-clinical populations, (c) be comprehensive enough to cover primary targets of parenting interventions focusing on improving children’s adjustment (reducing externalising and internalising problems and increasing prosocial and adaptive behaviours), (d) be applicable for interventions of different intensities and, (e) have the potential to be used as a population level indicator of the prevalence of behavioural and emotional problems of children. While we designed the measure to address a number of limitations in the literature, this study provides the results of an initial validation of this measure, and serves as the beginning of a broader program of research to evaluate the measure. We aimed to test the psychometric properties of the Child Adjustment and Parent Efficacy Scale (CAPES). Specifically we sought to: 1) apply principles of measure development to create a brief parent report, user friendly, public domain measure of children’s adjustment and parental self-efficacy in managing children’s behaviour; 2) determine the construct validity of the CAPES, and; 3) determine the internal consistency of the scale. Method Participants The sample consisted of 347 parents of children 2-12 years old who were recruited Australiawide from schools and day care centres, online forums, and parenting newsletters. The only eligibility criteria were that parents have a child between ages 2-12 years. Parents’ ages ranged from 24 to 58 years (M=39.49, SD=5.98). The majority of the sample self-identified as Caucasian/Australian (n=250, 72.1%) with the remaining identifying as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (n=7, 2.0%), Asian (n=5, 1.4%), or other (n=8, 2.3%)1. More mothers (n=295, 85.0%) than fathers (n=14, 4.0%) responded to the questionnaire. Children’s ages ranged from 2 to 12 years (M=7.34, SD=2.80) and there were more girls (n=180, 51.9%) than boys (n=129, 37.2%). A range of parental education attainment was represented with 166 (47.8%) having a university degree, 76 (21.9%) completing part or all of high school, and 67 (19.3%) completing trade or technical college. Most parents were married (n=229, 66.0%) and employed (n=239, 68.9%). The majority of parents (n=240, 69.2%) reported having no difficulties meeting essential household expenses, whereas 67 (19.3%) declared having problems meeting essential expenses over the last 12 months. Furthermore, 104 (30.0%) reported that they earn enough to comfortably purchase most of the things they really want, 146 parents (42.1%) declared that their earnings allow them to purchase only some things that they want, while 59 parents (17.0%) reporting they don’t have enough money to purchase much of anything they really want. Procedure Ethical clearance for the study was obtained in accordance with the ethical review processes of the University of Queensland. The following steps were taken in designing the measure: (1) definition of constructs; (2) review of existing measures; (3) generation of initial item pool; (4) input and feedback from key experts; (5) input and feedback from parents, and; (6) initial piloting to assess psychometric properties. In determining the construct domains for assessment, we focused on 1 Numbers do not add to 100% due to missing data. 3 Australian Psychologist (Accepted 19/2/14). 4 behavioural difficulties and anxiety, as these are the most prevalent types of difficulties experienced by children (Morawska & Sanders, 2011), and on child strengths and competencies to be consistent with interventions designed to improve child skills and self-regulatory abilities (e.g., Sanders, 2012). Furthermore, we wanted to integrate ratings of parenting efficacy which were domain specific, given the increasing focus on task-specific self-efficacy in the parenting literature (Jones & Prinz, 2005). We reviewed existing validated measures, including examining our own data from a range of intervention and population studies (e.g., Morawska & Sanders, 2006; Sanders et al., 2008) to identify common difficulties experienced by parents. The initial item pool was generated on the basis of this review in the context of our focus on child competencies. The initial scale was disseminated to a number of international experts in the parenting literature for feedback and to ensure wording and content were culturally relevant. Four in-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted with parents to gain feedback about ease of understanding, the completion process and face validity. Parents were asked to complete the questionnaire like they usually would and then to use a highlighter to mark anything on the questionnaire that was unclear or ambiguous. They were then asked a series of questions designed to elicit feedback (e.g., Is there anything that would make the survey easier to complete? Is there anything missing from the questionnaire that is important to you?). Feedback from the interviews indicated the measure was easy to understand and had high face validity however some parents recommended rewording items slightly. Several items were modified in response to expert and parent feedback, the order of items was changed and some items were dropped. This resulted in the final 30-item Child Adjustment and Parent Efficacy Scale (CAPES; Morawska & Sanders, 2010, see Appendix A). To ensure the revised measure could be understood by a wide range of parents it was assessed for readability using the Flesch reading ease and the Flesch-Kincaid grade tests. These tests assess comprehension difficulty and provide an estimate of education grade level (grade 1- 12) required for understanding. Scores of 65.1 (out of a possible 100 where higher scores indicate greater ease) and 9.5 (possible range 1-12) were obtained on the Flesch reading ease test and the Flesch-Kincaid grade tests respectively indicating the measure could be easily understood by a student aged 13-15 years or someone with a grade 9 level education. Following the measure development and consultation process initial piloting was conducted to assess the psychometric properties of the measure. An online survey was created and a large parent sample was recruited to complete the questionnaire. Recruitment was via school and childcare newsletters, online posts at parenting websites and via media releases. The number of parents who may have seen information about the survey but chose not to participate is unknown. Parents were directed to a website where they read a brief information sheet and provided informed consent prior to completing the questionnaire anonymously. Measures The Family Background Questionnaire (Sanders & Morawska, 2010) was used to assess family demographic characteristics, including child and parent age and gender, family composition, parent marital status, ethnicity and education and income. The Child Adjustment and Parent Efficacy Scale (CAPES; Morawska & Sanders, 2010) is a measure of child behavioural and emotional adjustment and parental efficacy. It consists of 30 items rated on a 4-point scale, ranging from not true of my child at all (0) to true of my child very much, or most of the time (3), where 20 items are two part questions that assess both child behaviour and parent efficacy. Twenty-six items assess behaviour concerns (e.g., My child rudely answers back to me) and behavioural competencies (Behaviour Scale; e.g., My child follows rules and limits), and four items assess emotional adjustment (Emotional Maladjustment Scale; e.g., My child worries). Some items are reverse scored. Items are summed to yield a total intensity score (Capes Intensity Scale: range of 0-90), which is made up of a behaviour score (range of 0-78) and an emotional maladjustment score (0-12) where high scores indicate higher levels of problems. The Self-efficacy Scale consists of 20 items and measures parents’ level of self-efficacy in managing child emotional and behavioural problems. Items are rated on a 10-point scale, ranging from certain I can't do it (1) to certain I can do 4 Australian Psychologist (Accepted 19/2/14). 5 it (10). A total efficacy score with a possible range of 20-200 is calculated by summing all efficacy items, with higher scores indicating a greater level of self-efficacy. Analytical Procedure Construct validity refers to the extent to which the scale measures what it is supposed to measure (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). In order to establish construct validity the factor structures of the CAPES Intensity and Self-efficacy were examined through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using AMOS v.20. The maximum likelihood estimation method was applied to the analysis of the covariance matrices2. The absolute goodness-of-fit of the models was evaluated using the χ2 test and three additional criteria: the comparative fit index (CFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) with 90% confidence interval, and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). The CFI index is a revised version of the Bentler and Bonett (1980) normed fit index that adjusts for degrees of freedom; values above .90 are considered adequate and above .95 as very good (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The RMSEA index indicates the error of approximation; values of less than .05 are considered good, though values as high as .08 are also considered reasonable (Browne & Cudeck, 1989). The SRMR index is an absolute measure of fit and represents the difference between the observed correlation and the predicted correlation; values close to .08 or less represent a good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Models were respecified based on Modification Indices (MIs), inspection of standardized residuals and theoretical considerations (Kline, 2011). The MIs values indicate the expected decrease in χ2 given the relaxation of imposed constraints; values < 5.00 indicate little appreciable improvement fit. A particularly high standardized residual for the covariance between two variables indicates that the relationship between those variables is not well accounted for by the model. In addition, to assess the extent to which a newly specified model exhibits an improvement over its predecessor, the χ2 difference test (Δχ2) was used. A significant Δχ2 indicates a substantial improvement in model fit. Convergent validity refers to the degree to which a set of measurement items appear to be indicators of one single underlying latent variable. Three approaches were applied to assess convergent validity: (1) we examined whether factor loadings for each indicator were statistically significant (Gerbing & Anderson, 1988); (2) checked that the estimate of the average variance extracted (AVE) that is shared between the construct and its measures is above .50 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981)3, and; (3) tested that estimates of composite reliability (CR) were above .704. Three approaches were also used to assess the discriminant validity of the measure. Discriminant validity refers to the extent to which items that measure one construct are different from the items that measure another construct. First, we analysed the correlations between the latent constructs, which should not be close or equal to 1.00. As an extension to this method we used a χ2 difference test (Bollen, 1989). In this test a model is analysed, in which the correlation between the factors is fixed at 1.00. The constrained model’s χ2 is compared to the original model’s χ2 where the correlation between the constructs is estimated freely. Discriminant validity is shown when the unconstrained model has a significantly lower chi-square value, indicating that the constructs are not perfectly correlated. The third method included the comparison of AVE to the squared interconstruct 2 The variance-covariance matrices available on request from the corresponding author. 3 The AVE estimate represents the average amount of variation that a latent construct is able to explain in the observed variables that theoretically relate to the construct. It is calculated by averaging the sum of squared factor loadings for each latent construct. The squared factor loading represents the amount of variation in each observed variable that the latent construct accounts for. When this variance is averaged across all observed variables that relate theoretically to the latent construct, we generate the AVE. 4 The composite reliability represents the overall reliability of a collection of heterogeneous yet similar items. It reflects the degree to which the scale score reflects one particular factor. It is calculated in the following way: CR = (sum of standardized factor loadings)2/ (sum of factor loadings)2 + (sum of indicator measurement error). 5 Australian Psychologist (Accepted 19/2/14). 6 correlation estimates (SIC); the AVE for each construct should be larger than the SIC among these constructs (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Internal consistency of CAPES Intensity and CAPES Self-efficacy was examined using Cronbach’s alphas computed in SPSS v.20. Values above .70 were considered good indicators of internal consistency (De Vaus, 2002) Results Preliminary Analyses Three hundred and seventy parents responded to the survey, but 23 of these provided only demographic data and did not complete the questionnaires; hence, they were excluded from analyses. For the remaining 347 respondents those who did not respond to any of the Intensity (n=1, 0.2%) or Self-efficacy (n=66, 19.0%) items were also excluded from analyses. This gave a total sample of n=346 for Intensity and n=281 for Self-efficacy. The expectation-maximization method in SPSS v.20 was used to handle missing data (<1.5% for both Intensity and Self-efficacy). A minimal recommended sample size in SEM studies is 200 cases (Kline, 2011). Recent simulation studies indicate that the recommended sample sizes for confirmatory factor analysis are N ≥ 200 for theoretical models and N ≥ 300 for the population models (Myers, Ahn, & Jin, 2011) In addition, empirical research of MacCallum, Widaman, Zhang, and Hong (1999) suggests that the adequacy of factor analysis results depends more on data characteristics (e.g. communalities) than on the sample size employed. When the communalities are high the sample size can be smaller. As can be seen in Figures 1-2, the communalities for the tested scales were moderate to high in size. Under these guidelines the available sample of 346 participants for CAPES Intensity and 281 participants for CAPES Self-efficacy are acceptable for testing models presented in Figures 1-2. Data were examined for departures from both univariate and multivariate normality, and for the presence of potential outliers. For 10 out of 30 Intensity items skewness and kurtosis estimates exceed the absolute value of 1 (average skewness and kurtosis were 0.77 and 0.36, respectively). The normalized estimate of Mardia’s coefficient of multivariate kurtosis was 93.42 with the Critical Ratio (C.R.) value of 19.83 indicating multivariate non-normality of the sample (Bentler, 2005; Byrne, 2010). In addition, univariate outliers were detected; as a result 277 (2.7%) extreme data points were transformed by changing the value to the next highest/lowest (non-outlier) number. A review of squared Mahalanobis distances (D2) showed minimal evidence of serious multivariate outliers (Byrne, 2010). In the case of Self-efficacy, for 14 out of 20 items skewness and kurtosis estimates exceed the absolute value of 1 (average skewness and kurtosis were -1.12 and 0.66, respectively). The normalized estimate of Mardia’s coefficient of multivariate kurtosis was 240.31 with C.R. value of 67.90 implying multivariate non-normality of the sample (Bentler, 2005; Byrne, 2010). Univariate outliers were also detected, and thus 151 (2.7%) of extreme data points were transformed by changing the value to the next highest/lowest (non-outlier) number. A review of D2 showed minimal evidence of serious multivariate outliers (Byrne, 2010). The deviation from normality of many items violated the assumptions on which normal theory maximum likelihood estimation technique is based. Thus, the factor validity of CAPES Intensity and Self-efficacy was assessed using a parcelling approach. A parcelling approach reduces bias caused by non-normal distributions and increases the stability of parameter estimates in a complex model (Coffman & MacCallum, 2005; Kishton & Widaman, 1994). Confirmatory Factor Analysis CFA using individual items was conducted to examine unidimensionality of the items and as a prerequisite to the subsequent parcelling. Examination of factor structure coefficients showed that for both CAPES Intensity and Self-efficacy none of the items exhibited problems; each item had a high and significant factor loading on its hypothesized factor. Construct validity evidence for Intensity and Self-efficacy was assessed using parcels-based CFA. At least 2 items (two observed variables) are needed to build a parcel. For adequate model identification at least three indicators are necessary within each factor (Kline, 2011), and as the Emotional maladjustment scale consists of four items, parcelling would violate this assumption. Four observed 6 Australian Psychologist (Accepted 19/2/14). 7 variables of the Emotional maladjustment subscale would be reduced to 2 parcels (2 items per parcel), which would cause identification problems. Therefore, for CAPES Intensity only items within the Behaviour subscale were parcelled. Each parcel represented an average of the two individual items. Items were combined in such a way as to maximize the normality of the resulting parcels. The detailed information on which items were combined into which parcels is listed in the footnote5. Validity of CAPES Intensity. The analysis of the factor structure of CAPES Intensity started with a single model factor (Model A) to serve as a comparison to the hypothesized two factor model. As Table 1 shows, the overall fit of the one-factor model to the data was poor, therefore it was rejected. In the next step a model with two correlated factors named Emotional maladjustment and Behaviour was tested (Model B). Model B showed much better fit to the data compared to Model A according to all fit indices. In addition, the change in the χ2 value between the one and two-factor model was significant, which also indicated that the two-factor model was adequate. Therefore we tested the two-factor model. As presented in Table 1, Model B achieved acceptable fit according to the SRMS and RMSEA, but not according to χ2 and CFI. A statistically significant lack of fit as indexed by χ2 difference test is quite typical in social sciences research because of the sensitivity of the test in large samples or with many degrees of freedom (Byrne, 2010). Nevertheless, the CFI index showed that the model could be improved. Inspection of standardized residuals indicated that Model B did not adequately account for the associations between Parcel 5 (Item 12 “My child misbehaves at school or day care” & Item 28 “My child gets on well with other children”) and Item 27 (“My child seems to feel good about him/herself’). To assess the extent to which these items contaminate the factor validity of CAPES Intensity, a second model (Model C) was specified, in which Parcel 5 and Item 16 were deleted. As expected, results demonstrated a significant improvement in fit (see Table 1). However, the CFI value below .95 indicated that a certain degree of model misfit remained. A review of MIs revealed that the model fit could be improved by allowing several of the error terms to correlate. These modifications were made one at a time until the fit indices met the cut-off criteria for acceptable levels. All correlations between error terms were theoretically sound. In Model D we allowed the correlations between error terms of Parcel 2 (Items 2 and 16) and Parcel 12 (Items 6 and 10), both containing items referring to child’s non-compliance and disobedience. In Model E we allowed the correlation between error terms of Parcel 3 (Items 4 and 14) and Parcel 13 (Items 23 and 30), both comprised of items referring to child’s tantrum outburst and immaturity. Finally in Model F we allowed correlation between error terms of Parcel 9 (Items 25 and 26) and Parcel 11 (Items 8 and 20), both comprising of items referring to personal independence and social ability with others. As shown in Table 1, fit values based on CFI, SRMR and RMSEA indicated that a reasonable amount of data was explained by Model F [χ2(86)=174.88, p<.001; CFI=.952; SRMR=.052; RMSEA=.055 (90% CI .043-.066)]. The chi-square difference between Model E and Model F was 8.99 (df=1) indicating a significant improvement (p<.001) of model fit. Thus, further fitting of the model would clearly represent an overfit (Byrne, 2010). Therefore, Model F was selected as an adequate description of the data. A graphic illustration of the final model is presented in Figure 1. The AVE estimate for the Behaviour scale reached the value of .40, slightly lower than the recommended cut-off value of .50. For Emotional maladjustment the AVE estimate reached the value of .51, exceeding the recommended cut-off value of. 50. The CR estimates for both, Behaviour and Emotional maladjustment were above .70 (.95 and .85, respectively). In addition, all items and parcels 5 For the CAPES Intensity, Behavior subscale: Parcel 1 included items 24 & 1, Parcel 2 included items 2 &16, Parcel 3 included items 4 &14, Parcel 4 included items 5 &7, Parcel 5 included items 12 &28, Parcel 6 included items 9 &18, Parcel 7 included items 21 &13, Parcel 8 included items 15 &17, Parcel 9 included items 25 &26, Parcel 10 included items 22 &29, Parcel 11 included items 8 &20, Parcel 12 included items 6 &10, Parcel 13 included items 23 &30. For the CAPES Confidence: Parcel 1 included items 1 &2, Parcel 2 included items 3 &4, Parcel 3 included items 5 &6, Parcel 4 included items 7 &8, Parcel 5 included items 9 &10, Parcel 6 included items 11 &12, Parcel 7 included items 12 &16, Parcel 8 included items 13 &14, Parcel 9 included items 17 &18, Parcel 10 included items 19 &20. 7 Australian Psychologist (Accepted 19/2/14). 8 had significant loadings >.40 on the factors they were specified to measure (Stevens, 1992). The lowest factor loading on the Behaviour scale was .45 and the highest was .81. The factor loadings on the Emotional maladjustment scale ranged from .67 to .79. These results indicate that CAPES Intensity exhibited adequate convergent validity. The correlation between the two factors was moderate (r=.36, p<.001). A model with fixed correlation between the two factors was compared to one in which correlation was freely estimated. The two models differed significantly [Δχ2(1)=386.96-174.88=212.08, p<.001], indicating that the better model is the one in which the two constructs are viewed as distinct, yet correlated factors. The SIC between the two factors reached the value of .13 and was much lower than the AVE estimates for both Behaviour (.40) and Emotional maladjustment (.51). These results imply strong evidence for discriminant validity of the two-factor model of CAPES Intensity. Validity of CAPES Self-efficacy. The analysis of the factor structure of CAPES Self-efficacy started with the hypothesized single factor model (Model A). As Table 2 shows, Model A achieved acceptable fit according to the CFI and SRMS, but not according to χ2 and RMSEA. Inspection of standardized residuals indicated that Model A adequately accounted for the associations between the variables. A review of MIs revealed that the model fit could be improved by allowing several of the parcels’ errors to correlate. These modifications were made one at time until the fit indices met the cut-off criteria for acceptable levels. All correlations between error terms were theoretically sound. In Model B we allowed the correlations between error terms of Parcel 6 (Items 11 and 12) and Parcel 10 (Items 19 and 20), both containing items referring to child fears and anxieties as well as conduct problems. In Model C we allowed the correlation between error terms of Parcel 2 (Items 3 and 4) and Parcel 7 (Items 12 and 16), both comprised of items referring to child’s tantrum outburst and misbehaviour at school and at home. Finally in Model D we allowed correlation between error terms of Parcel 3 (Items 5 and 6) and Parcel 4 (Items 7 and 8), both comprising of items referring to child’s conduct problems during mealtimes and dressing up. As shown in Table 2 fit values based on CFI, SRMR and RMSEA indicated that a reasonable amount of data was explained by Model D [χ2(32)=89.06, p<.001; CFI=.980; SRMR=.022; RMSEA=.080 (90%CI .060-.100)]. The chi-square difference between Model D and Model E was 12.92 (df=1) indicating a significant improvement (p<.001) of model fit. Thus, further fitting of the model would clearly represent an overfit (Byrne, 2010). Therefore Model D was selected as an adequate description of the data. A graphic illustration of the final model is presented in Figure 2. The AVE estimate for CAPES Self-efficacy reached the value of .72, indicating sufficient amount of variance explained by the construct. The CR estimate for the scale reached the value of .88 indicating good internal consistency of the construct. Furthermore, all parcels had significant loadings >.40 (range from .75 to .89) on the hypothesized factor (Stevens, 1992). These results indicate good convergent validity for CAPES Self-efficacy. As CAPES Self-efficacy is unifactorial, the Self-efficacy construct was compared against the Behaviour and Emotional maladjustment constructs of CAPES Intensity. The two scales were tested in one model. The correlations between Self-efficacy and Behaviour and Emotional maladjustment constructs were moderate (r=-.33 and r=-.65, p<.001, respectively). The chi-square difference tests indicated that discriminant validity was achieved between Self-efficacy and Behaviour [Δχ2(1)=1263.32-878.68=384.64, p<.001] and between Self-efficacy and Emotional maladjustment [Δχ2(1)=1046.60-878.68=167.92, p<.001]. The SIC reached the value of .11 for the relation with the Behaviour construct, which is lower than the AVE estimates for both Behaviour (.40) and Selfefficacy (.72). Further, the SIC estimate reached the value of .42 for the relation with the Emotional maladjustment construct, which is lower than the AVE estimates for both Emotional maladjustment (.51) and Self-efficacy (.72). These results imply strong evidence for discriminant validity of the onefactor measurement model of CAPES Self-efficacy. Reliability For CAPES Intensity Cronbach’s alphas were .90 (Total scale score), .90 (Behaviour) and .74 (Emotional maladjustment). The Cronbach’s alpha for CAPES Self-efficacy was .96. Thus, 8 Australian Psychologist (Accepted 19/2/14). 9 Cronbach’s alphas were above the recommended cut-off value of .70 for good internal consistency of the measure (De Vaus, 2002). Discussion The present study used an expert informant approach to construct a brief, easy to administer, valid measure of children’s adjustment that could be used in both population-based and individual clinical outcome evaluations of parenting interventions. We also sought to determine the psychometric properties of the CAPES as a measure of child adjustment including the validation of the factor structure and reliability of the scale, and a measure of parental self-efficacy in managing children’s problem behaviours. With respect to the measure development process we harnessed the views of experienced international parenting researchers and clinicians to identify an item pool of 30 items that would provide a brief, valid measure of both externalizing and internalizing difficulties that could be subjected to psychometric evaluation. The resulting scale has the advantage of including items that address both externalizing and internalizing problems as well as prosocial behaviours of children. The relatively wide age range 2-12 for the scale means it could potentially be used in longitudinal studies or in follow up evaluations of early intervention programs targeting families. The readability of the scale indicated it could be comfortably read by parents with a grade 9 education level. Both the CAPES Intensity and Self-efficacy scales proved to be psychometrically sound measures. Confirmatory factor analysis supported a 27-item, two-subscale structure of the CAPES Intensity. The findings suggested that three items require either deletion or content modification. Two of these items, 12“My child misbehaves at school or day care” and 28 “My child gets on well with other children” were designed to measure the child’s behaviour problems. These items may not have fit well because they reflect behaviour out of the home setting. Item 27 “My child seems to feel good about him/herself’ may not be a valid indicator of child’s emotional adjustment. Furthermore, CAPES Intensity showed reasonable convergent validity as measured by average variance extracted estimates, the composite reliability estimates and examination of factor loadings. In other words, the CAPES Intensity items appear to be good indicators of the two constructs, Behaviour and Emotional maladjustment, they were designed to measure. In terms of discriminant validity, the results confirmed that the two subscales of CAPES Intensity, Behaviour and Emotional maladjustment represent two distinct, yet correlated constructs. Evidence also suggested that CAPES Intensity is an internally consistent measure. As far as CAPES Self-efficacy is concerned, confirmatory factor analysis supported a 20-item, 1-factor structure of the scale. Regarding construct validity, CAPES Self-efficacy showed good convergent and discriminant validity. The results indicated that the 20 items of CAPES Self-efficacy appear to be indicators of the one latent construct - parental self-efficacy. To test the discriminant validity of CAPES Self-efficacy its factor structure was compared against the Behaviour and Emotional maladjustment constructs of CAPES Intensity. The analyses indicated that parental Selfefficacy represents a distinct construct to both the Behaviour and Emotional maladjustment constructs of CAPES Intensity. Moreover, CAPES Self-efficacy demonstrated excellent internal consistency. The advantage of having several developmentally important constructs related to children’s social competence, mental health and wellbeing (e,g., conduct problems, emotional difficulties, prosocial behaviour) and a construct related to the quality of the family environment (Viz parental efficacy) in the one scale is that these problems can be concurrently assessed and potential targets for both child and parental intervention identified. In evidence based parenting and family based prevention and treatment programs parental self-efficacy is often a primary target of intervention and changes in parental self-efficacy are frequently associated with reductions in children’s behavioural and emotional problems (Sanders & Mazzucchelli, 2012). This study provides the first evidence that the psychometric properties of the CAPES make it a potentially useful measure, and serves as the basis for a more extensive evaluation of the measure and application across a range of contexts. The findings of this initial validation study need to take into account a number of limitations. Firstly, while the sample size was reasonable, we did not specifically include clinical cases. Future studies should examine more heterogeneous groups and 9 Australian Psychologist (Accepted 19/2/14). 10 include multiple-group analysis to examine equivalence between clinical and non-clinical populations, mothers and fathers, boys and girls as well as different age groups of children. As the initial psychometric evaluation was promising further research is warranted to establish age and gender specific norms, and cut offs to determine clinical caseness of the CAPES Intensity scale when used with children with or at risk of serious mental health problems. In addition, the current Emotional maladjustment subscale is made up of a very small number of items, and indeed there is limited assessment of child sadness and anxiety. Further extension of this subscale is required, particularly as several items were removed during the initial piloting and subsequent analysis stages. Notwithstanding these limitations further psychometric investigation of the scale in the context of prevention and treatment studies are required to establish the change sensitivity of the measure in trials of parenting programs. An initial study by Morawska, Tometzki and Sanders (2012) examining this possibility showed that the CAPES scores successfully captured improvements in children conduct problems following parents’ participation in a version of the Triple P-Positive Parenting Program delivered as a radio podcast intervention. The validation also needs to be extended to more diverse samples in terms of sex, age and ethnicity. Further, there is a need for evaluation of the validity of CAPES by investigating patterns of relationships between CAPES and other measures assessing similar and different constructs. Research is also warranted to examine the cross cultural robustness of the scale. Finally, studies examining the convergent and discriminant validity of the CAPES would be useful to determine the extent to which the intensity scale correlates with other measures of the same constructs including independent behavioural observations of child behaviour, parenting behaviour, parent-child interaction and teacher assessment of behavioural and emotional problems. The CAPES has good potential both as a clinical and research tool and is currently being used and evaluated across varying contexts and cultures where is it demonstrating good psychometric properties (e.g., Mejia, Filus, Calam, Morawska, & Sanders, 2014; Sumargi, Sofronoff, & Morawska, 2013). Its strength lies in its brevity and assessment of both child behaviour and parenting efficacy in a single measure, which has significant benefits in assessment in a clinical setting where a psychologist may need to assess a variety of areas to effectively formulate and to offer a tailored intervention. 10 Australian Psychologist (Accepted 19/2/14). 11 References Achenbach, T. M. (2000). Child Behavior Checklist 1½-5. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry. Bagner, D. M., Rodríguez, G. M., Blake, C. A., Linares, D., & Carter, A. S. (2012). Assessment of behavioral and emotional problems in infancy: A systematic review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 15(2), 113-128. doi: 10.1007/s10567-012-0110-2 Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191-215. Bandura, A. (1997). Self efficacy: the exercise of control. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. Bandura, A. (2000). Self-efficacy: the foundation of agency. In W. J. Perrig & A.Grob (Eds.), Control of human behavior, mental processes, and consciousness. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. Bentler, P. M. (2005). EQS 6 Structural equations program manual. Encino, CA: Multivariate Software. Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance Tests and Goodness of Fit in the Analysis of Covariance-Structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88(3), 588-606. doi: 10.1037/00332909.88.3.588 Biglan, A., Flay, B. R., Embry, D. D., & Sandler, I. N. (2012). The Critical Role of Nurturing Environments for Promoting Human Well-Being. American Psychologist, 67(4), 257–271. doi: 10.1037/a0026796 Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. New York: Wiley. Briggs-Gowan, M. J., Carter, A. S., McCarthy, K., Augustyn, M., Caronna, E., & Clark, R. (2013). Clinical Validity of a Brief Measure of Early Childhood Social–Emotional/Behavioral Problems. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 38(5), 577-587. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jst014 Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1989). Single Sample Cross-Validation Indexes for CovarianceStructures.Multivariate Behavioral Research, 24(4), 445-455. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2404_4 Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts,applications, and programming. Mahwah, NJ US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. Coffman, D. L., & MacCallum, R. C. (2005). Using parcels to convert path analysis models into latent variable models. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 40(2), 235-259. Collins, W. A., Maccoby, E. E., Steinberg, L., Hetherington, E. M., & Bornstein, M.H. (2000). Contemporary research on parenting: The case for nature and nurture. American Psychologist, 55, 218-232. Conners, C. K. (2009). Conners Rating Scales-Revised (CRS-R). Toronto, Ontario, Canada: MultiHealth Systems. De Vaus, D. A. (2002). Analyzing social science data. London: SAGE. Eyberg, S. M., & Pincus, D. (1999). Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory and Sutter-Eyberg Student Behavior Inventory - Revised: Professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 39-50. doi: 10.2307/3151312 Gerbing, D. W., & Anderson, J. C. (1988). An Updated Paradigm for Scale Development Incorporating Unidimensionality and Its Assessment. Journal of Marketing Research, 25(2), 186-192. doi: 10.2307/3172650 Goodman, R. (1997). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38, 581-586. Goodman, R. (2001). Psychometric Properties of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(11), 1337-1345. Goodman, R., & Scott, S. (1999). Comparing the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire and the Child Behavior Checklist: Is Small Beautiful? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 27(1), 17-24. doi: 10.1023/a:1022658222914 11 Australian Psychologist (Accepted 19/2/14). 12 Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria Versus New Alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling-a Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1-55. doi: Doi 10.1080/10705519909540118 Johnston, C., & Mash, E. J. (1989). A measure of parenting satisfaction and efficacy. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 18, 167-175. Jones, T. L., & Prinz, R. J. (2005). Potential roles of parental self-efficacy in parent and child adjustment: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 25(3), 341-363 doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.12.004 Kishton, J. M., & Widaman, K. F. (1994). Unidimensional Versus Domain Representative Parceling of Questionnaire Items - an Empirical Example. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 54(3), 757-765. doi: 10.1177/0013164494054003022 Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). New York: Guilford Press. Kovacs, M. (2010). Children's Depression Inventory 2. Toronto, Ontario, Canada:Multi-Health Systems. MacCallum, R. C., Widaman, K. F., Zhang, S., & Hong, S. (1999). Sample size in factor analysis. Psychological Methods, 4(1), 84-99. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.4.1.84 Mejia, A., Filus, A., Calam, R., Morawska, A., & Sanders, M. R. (2014). Translation and validation of the CAPES in Spanish: A brief instrument for assessing child maladjustment and parent efficacy. Submitted for publication. Mieloo, C., Raat, H., Oort, F. v., Bevaart, F., Vogel, I., Donker, M., & Jansen, W. (2012). Validity and Reliability of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire in 5–6 Year Olds: Differences by Gender or by Parental Education? PLoS One, 7(5), e36805. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036805 Morawska, A., & Sanders, M. R. (2006). Self-directed behavioural family intervention. International Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy, 2, 332-340. Morawska, A., & Sanders, M. R. (2007). Concurrent predictors of dysfunctional parenting and parental confidence: Implications for parenting interventions. Child: Care, Health & Development, 33, 757-767. Morawska, A., & Sanders, M. R. (2010). The Child Adjustment and Parent Efficacy Scale (CAPES). Brisbane: Parenting and Family Support Centre. Morawska, A., & Sanders, M. R. (2011). Disorders of Childhood. In E. Rieger (Ed.),Abnormal Psychology: Leading Researcher Perspectives (2nd ed., pp. 403-447). Sydney: McGraw-Hill Australia. Morawska, A., Tometzki, H., & Sanders, M. R. (2012). An Evaluation of the Efficacy of a Triple PPositive Parenting Program Podcast Submitted for publication. Myers, N., Ahn, S., & Jin, Y. (2011). Sample Size and Power Estimates for a Confirmatory Factor Analytic Model in Exercise and Sport: A Monte Carlo Approach. [Article]. Research Quarterly for Exercise & Sport, 82(3), 412. Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory 3rd edition: McGrawHill. Palmieri, P. A., & Smith, G. C. (2007). Examining the Structural Validity of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) in a U.S. Sample of Custodial Grandmothers. Psychological Assessment, 19(2), 189-198. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.2.189 Sanders, M. R. (2012). Development, Evaluation, and Multinational Dissemination of the Triple PPositive Parenting Program. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 8, 345-379. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143104 Sanders, M. R., Markie-Dadds, C., Tully, L. A., & Bor, W. (2000). The Triple P- Positive Parenting Program: A comparison of enhanced, standard, and self-directed behavioral family intervention for parents of children with early onset conduct problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(4), 624-640. doi: 10.1037//002-006X.68.4.624 Sanders, M. R., & Morawska, A. (2010). Family Background Questionnaire. Brisbane: Parenting and Family Support Centre. 12 Australian Psychologist (Accepted 19/2/14). 13 Sanders, M. R., Ralph, A., Sofronoff, K., Gardiner, P., Thompson, R., Dwyer, S., & Bidwell, K. (2008). Every Family: A population approach to reducing behavioural and emotional problems in children making the transition to school. Journal of Primary Prevention, 3, 197-222. doi: 10.1007/s10935-008-0139-7 Sanders, M. R., & Woolley, M. L. (2005). The relationship between maternal self-efficacy and parenting practices: Implications for parent training. Child: Care, Health & Development, 31(1), 65-73. Smedje, H., Broman, J.-E., Hetta, J., & von Knorring, A.-L. (1999). Psychometric properties of a Swedish version of the "Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire". European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 8(2), 63-70. Spence, S. H. (1998). A measure of anxiety symptoms among children. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36, 545-566. Stevens, J. (1992). Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences: Lawrence Erlbaum. Sumargi, A., Sofronoff, K., & Morawska, A. (2013). Understanding Parenting Practices and Parents' Views of Parenting Programs: A Survey Among Indonesian Parents Residing in Indonesia and Australia. In Press: Journal of Child and Family Studies Accepted 1/8/13. Tsang, K. L. V., Wong, P. Y. H., & Lo, S. K. (2012). Assessing psychosocial well‐being of adolescents: A systematic review of measuring instruments. Child: Care, Health and Development, 38(5), 629-646. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01355.x Vimpani, G., Patton, G., & Hayes, A. (2002). The relevance of child and adolescent development for outcomes in education, health and life success. In A. Sanson (Ed.), Children's health and development: New research directions for Australia (pp. 14-37). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Webster-Stratton, C., & Reid, M. J. (2003). Treating conduct problems and strenghtening social and emotional competence in young children: The dina dinosuar treatment program. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 11, 130-143. 13 Australian Psychologist (Accepted 19/2/14). 14 Table 1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Factor Structure of CAPES Intensity. Model χ2 df Δχ2 Δdf CFI SRMR RMSEA RMSEA 90% CI Pre-test A 701.71** 119 .742 .100 .128 .111 - .128 One-factor B 408.31** 118 293.40** 1 .871 .075 .084 .076 - .093 Two-factor Post-test C Parcel 5 & item 207.04** 89 201.27** 29 .936 .055 .062 .051 - .073 16 deleted D with correlated 196.40** 88 10.64** 1 .941 .055 .060 .049 - .071 error between Parcels 2 & 12 E with correlated 183.87** 87 12.53** 1 .947 .053 .057 .045 - .068 error between Parcels 3 & 13 F with correlated 174.88** 86 8.99** 1 .952 .052 .055 .043 - .066 error between Parcels 9 & 11 Notes: df = degrees of freedom, CFI = comparative fit index, SRMR = standardized root mean square residual, RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation, CI = confidence interval. Models A to F are based on N = 346. The chi square test is used to test the newly specified model with the previous one (only if the models are nested, i.e., if one of the models could be obtained simply by fixing/ eliminating parameters of the other model). This means that in the above Table Δχ2 test show the results for comparisons of: the Model B with Model A; Model C with Model B; Model D with Model C; Model E with Model D and Model F with Model E, respectively. **p < .001 14 Australian Psychologist (Accepted 19/2/14). 15 Table 2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Factor Structure of CAPES Self-efficacy. Model χ2 df Δχ2 Δdf CFI SRMR RMSEA RMSEA 90% CI .103 - .138 A 176.58** 35 .950 .031 .120 B with correlated 129.84** 34 46.74** 1 .966 .027 .100 .081 - .119 error between Parcels 6 & 10 C with correlated 101.98** 33 27.86** 1 .976 .023 .086 .068 - .106 error between Parcels 2 & 7 D with correlated 89.06** 32 12.92** 1 .980 .022 .080 .060 - .100 error between Parcels 3 & 4 Notes: df = degrees of freedom, CFI = comparative fit index, SRMR = standardized root mean square residual, RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation, CI = confidence interval. Models A to D are based on N = 281. The chi square test is used to test the newly specified model with the previous one (only if the models are nested, i.e., if one of the models could be obtained simply by fixing/ eliminating parameters of the other model). This means that in the above Table Δχ2 test show the results for comparisons of: the Model B with Model A; Model C with Model B; Model D with Model C. **p < .001 15 Australian Psychologist (Accepted 19/2/14). 16 Figure 1 2-Factor Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the 27-item CAPES Intensity with 3 Error Covariances and Standardized Estimates. Item 5 .67 Item 17 Item 29 .79 Emotional Maladjustment .68 .36 Parcel 1 .81 -.18 Behaviour Parcel 2 .73 -.22 Parcel 3 .81 -.17 Parcel 4 Parcel 6 .54 .76 .47 Parcel 7 .62 Parcel 8 .54 Parcel 9 .53 .45 Parcel 10 .68 Parcel 11 .56 Parcel 12 Parcel 13 16 χ2 (86) = 174.88, p < 0.001; CFI = .952; SRMR = .052; RMSEA = .055 (90% CI .043 - .066) Australian Psychologist (Accepted 19/2/14). 17 Figure 2 1-Factor Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the 20-item CAPES Self-efficacy with 3 Error Covariances and Standardized Estimates. Parcel 1 .86 Parcel 2 .85 Confidence Parcel 3 .87 .23 Parcel 4 .75 -.38 Parcel 5 .87 .84 Parcel 6 .85 Parcel 7 .89 .40 Parcel 8 Parcel 9 .89 .80 Parcel 10 17 χ2 (32) = 89.06, p < 0.001; CFI = .980; SRMR = .022; RMSEA = .080 (90% CI .060 - .100) Australian Psychologist (Accepted 19/2/14). 18 Appendix A Child Adjustment and Parent Efficacy Scale (CAPES) Please read each statement and select a number 0, 1, 2 or 3 that indicates how true the statement was of your child (aged 2-12) over the past four (4) weeks. Then, using the scale provided, write down the number next to each item that best describes how confident you are that you can successfully deal with your child’s behaviour, even if it is a behaviour that rarely occurs or does not concern you. There are no right or wrong answers. Do not spend too much time on any statement. Example: My child: Gets upset or angry when they don’t get their own way 0 1 2 3 9 The rating scale is as follows: 0. Not true of my child at all 1. True of my child a little, or some of the time 2. True of my child quite a lot, or a good part of the time 3. True of my child very much, or most of the time How true is this of your child? My child: 1. ets upset or angry when they don’t get their own way 2. efuses to do jobs around the house when asked 3. orries 4. oses their temper 5. isbehaves at mealtimes 6. rgues or fights with other children, brothers or sisters 7. efuses to eat food made for them 8. akes too long getting dressed 9. urts me or others (e.g., hits, pushes, scratches, bites) 10. nterrupts when I am speaking to others 11. eems fearful and scared 12. isbehaves at school or daycare 13. 18 Not at all A little Quite a lot Very much 0 1 2 G3 0 1 2 R 3 0 1 2 W3 0 1 2 L 3 0 1 2 M3 0 1 2 A 3 0 1 2 R 3 0 1 2 T 3 0 1 2 H3 0 1 2 I 3 0 1 2 S 3 0 1 2 M3 0 1 2 H3 Rate your confidence 1 = Certain I can’t do it 10 = Certain I can do it Australian Psychologist (Accepted 19/2/14). 19 as trouble keeping busy without adult attention 14. ells, shouts or screams 15. hines or complains (whinges) 16. cts defiant when asked to do something 17. ries more than other children their age 18. udely answers back to me 19. eems unhappy or sad 20. as trouble organising tasks and activities 0 1 2 Y 3 0 1 2 W3 0 1 2 A 3 0 1 2 C 3 0 1 2 R 3 0 1 2 S 3 0 1 2 H3 How true is this of your child? My child: 21. an keep busy without constant adult attention 22. ooperates at bedtime 23. an do age appropriate tasks by themselves 24. ollows rules and limits 25. ets on well with family members 26. s kind and helpful to others 27. eems to feel good about themselves 28. ets on well with other children 29. alks about their views, ideas and needs appropriately 30. oes what they are told to do by adults 19 Not at all A little Quite a lot Very much 0 1 2 C 3 0 1 2 C 3 0 1 2 C 3 0 1 2 F 3 0 1 2 G3 0 1 2 I 3 0 1 2 S 3 0 1 2 G3 0 1 2 T 3 0 1 2 D3 Australian Psychologist (Accepted 19/2/14). 20 Appendix B Table 3 Descriptive statistics for the items of CAPES Intensity Scale. Item Mean SD Range (min-max) Item 1 2.62 .82 3 (1-4) Item 2 2.03 .79 3 (1-4) Item 3 2.21 .88 3 (1-4) Item 4 2.02 .93 3 (1-4) Item 5 1.86 .87 3 (1-4) Item 6 2.30 .85 3 (1-4) Item 7 1.73 .85 3 (1-4) Item 8 1.97 .98 3 (1-4) Item 9 1.46 .70 3 (1-4) Item 10 2.46 .89 3 (1-4) Item 11 1.55 .75 3 (1-4) Item 12 1.53 .82 3 (1-4) Item 13 1.70 .86 3 (1-4) Item 14 2.02 .91 3 (1-4) Item 15 2.20 .78 3 (1-4) Item 16 1.97 .81 3 (1-4) Item 17 1.41 .75 3 (1-4) Item 18 1.92 .83 3 (1-4) Item 19 1.55 .72 3 (1-4) Item 20 1.81 .89 3 (1-4) Item 21 3.14 .87 3 (1-4) Item 22 3.06 .95 3 (1-4) Item 23 3.65 .67 3 (1-4) Item 24 3.12 .76 3 (1-4) Item 25 3.42 .79 3 (1-4) Item 26 3.24 .75 3 (1-4) Item 27 3.17 .84 3 (1-4) Item 28 3.34 .79 3 (1-4) Item 29 3.10 .79 3 (1-4) Item 30 3.25 .76 3 (1-4) 20 Skew .29 .66 .57 .70 .74 .53 1.06 .70 1.51 .32 1.36 1.55 1.12 .65 .63 .71 1.93 .76 1.37 .90 -.63 -.64 -2.10 -.40 -1.23 -.64 -.72 -1.00 -.36 -.69 Kurtosis -.73 .29 -.25 -.31 -.24 -.24 .50 -.55 1.87 -.69 1.59 1.68 .51 -.32 .27 .29 3.17 .17 1.94 -.03 -.55 -.64 4.20 -.61 .72 -.28 -.26 .30 -.82 -.15 Australian Psychologist (Accepted 19/2/14). 21 Table 4 Descriptive statistics for the items of CAPES Self-efficacy Scale. Item Mean SD Range (min-max) Item 1 7.35 2.25 9 (1-10) Item 2 7.82 2.23 9 (1-10) Item 3 7.41 2.24 9 (1-10) Item 4 7.70 2.38 9 (1-10) Item 5 7.98 2.27 9 (1-10) Item 6 7.33 2.23 9 (1-10) Item 7 8.07 2.24 9 (1-10) Item 8 8.12 2.18 9 (1-10) Item 9 8.21 2.44 9 (1-10) Item 10 7.65 2.10 9 (1-10) Item 11 7.99 2.23 9 (1-10) Item 12 8.20 2.24 9 (1-10) Item 13 8.26 1.95 9 (1-10) Item 14 7.66 2.35 9 (1-10) Item 15 7.58 2.24 9 (1-10) Item 16 7.70 2.23 9 (1-10) Item 17 8.32 2.23 9 (1-10) Item 18 7.73 2.39 9 (1-10) Item 19 7.83 2.40 9 (1-10) Item 20 7.95 2.06 9 (1-10) 21 Skew -.79 -1.07 -.87 -1.10 -1.14 -.71 -1.21 -1.28 -1.47 -.95 -1.25 -1.46 -1.43 -.97 -.84 -.92 -1.55 -1.04 -1.13 -1.15 Kurtosis -.01 .53 .16 .52 .51 -.24 .73 .90 1.29 .58 1.01 1.64 1.95 .14 -.16 -.02 1.75 .16 .45 1.07

© Copyright 2025