Monitoring trends in recreational drug use from the analysis of

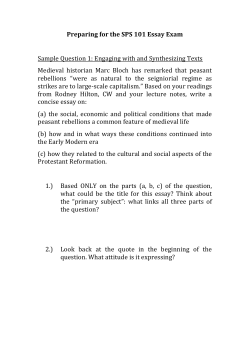

Q J Med 2013; 106:1111–1117 doi:10.1093/qjmed/hct183 Advance Access Publication 17 September 2013 Monitoring trends in recreational drug use from the analysis of the contents of amnesty bins in gay dance clubs T. YAMAMOTO1, A. KAWSAR2, J. RAMSEY3, P.I. DARGAN1,4 and D.M. WOOD1,4 From the 1Department of Clinical Toxicology, Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and King’s Health Partners, Westminster Bridge Road, London, SE1 7EH, UK, 2Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London, London, E1 2AD, UK, 3TICTAC Communications Ltd., St. George’s University of London, London, SW17 0RE, UK, and 4King’s College London, Guy’s Campus, London, SE1 1UL, UK Address correspondence to Dr. Takahiro Yamamoto, Department of Clinical Toxicology, St Thomas’ Hospital, Westminster Bridge Road, London, UK SE1 7EH. email: takahiro.yamamoto@gstt.nhs.uk Received 15 July 2013 and in revised form 21 August 2013 Background: In 2011/12, 8.9% of the UK population reported use of recreational drugs. Problems related to drug use is a major financial burden to society and a common reason for attendance to hospital. Aim: The aim of this study was to establish current trends in recreational drug use amongst individuals attending gay-friendly nightclubs in South London. Method: Contents of drug amnesty bins located at two night clubs were documented and categorized into powders, herbal products, liquids, tablets and capsules. These were then sent to a Home Office licensed laboratory for identification through a preexisting database of almost 25 000 substances. If required, further qualitative analysis was performed. Results: A total of 544 samples were obtained. Of them, 240 (44.1%) were liquids, 220 (40.4%) powders, 42 (7.7%) herbal and 41 (7.5%) tablets or capsules. Gamma-butyrolactone (GBL) was the most common liquid drug (n = 160, 66.7%) followed by poppers (n = 72, 30.0%). Powders provided the widest range of drugs with mephedrone being the most common (n = 105, 47.7%) followed by ketamine (n = 28, 12.7%), 3,4-methylenedioxy-Nmethylamphetamine (MDMA) (n = 26, 11.8%), and cocaine (n = 21, 9.5%). Tablets and capsules included medicinal drugs, recreational drugs and plaster of Paris tablets that mimicked the appearance of ‘ecstasy’ tablets. Conclusions: This study has provided a snapshot of the pattern of drug use in the gay community which compliments findings of the self-reported surveys and other studies from the same population. The information obtained will be helpful in guiding in designing harm reduction interventions in this community and for monitoring the impact of changes in legislation. Introduction interest to health professionals and local/national organizations for designing prevention, education and treatment approaches for problems related to drug use. Self-reported surveys are often used to identify and measure trends in drug use.4–6 In 1996, questions were added to the then British Crime Survey (now Crime Survey for England and Wales)1 to examine drug use amongst 16–59 year olds. In 2011/2012, A total of 8.9% of the UK population reported using recreational drugs in 2011/20121 and use is a common reason for presentation to an emergency department (6.9% of all attendances).2 Drug use is also a major financial burden to society, costing £15.4 billion a year in the UK.3 Therefore knowledge of current trends in the use of recreational drugs is of ! The Author 2013. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Association of Physicians. All rights reserved. For Permissions, please email: journals.permissions@oup.com Downloaded from by guest on December 29, 2014 Summary 1112 T. Yamamoto et al. bins, and whether the analytical results were comparable with self-reported surveys in individuals attending the same clubs. Methods Sample collection This opportunistic study, undertaken in South East London in September 2011, was made possible through joint co-operation between the nightclubs, the police and ourselves. Amnesty bins were located in two ‘gay-friendly’ nightclubs and the samples collected in the bins during club opening hours. Samples were placed in sealed police evidence bags and delivered securely by the Metropolitan Police to a Home Office-licensed drug database company situated at St. George’s, University of London. Sample analysis The analytical methods used have been previously described17 (Figure 1). Contents were categorized into liquids, powders, tablets, capsules and herbal products. Attempts were then made to visually identify all solid preparations using the pre-existing TICTAC (The Identification CD-ROM for Tablets and Capsules) database of nearly 25 000 known products.20 A sample from each batch (determined as products of the same size, colour and markings) was then subjected to a Marquis Test21 for confirmation of contents. If the findings were inconclusive, further qualitative analysis was performed by Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (GC–MS). Liquid and powder samples were initially analysed using Attenuated Total Reflectance Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (ATR FTIR). If further analysis was required, these were also analysed by GC–MS. Herbal products (incorporating substances including herbs, herbal materials, herbal preparations and herbal products that contain the active ingredients of the plant or plant materials)22 were identified by visual inspection only and were not tested further. Results A total of 544 samples were obtained; 240 samples (44.1% of the total) were liquids, 220 (40.4%) powder, 42 (7.7%) herbal and 41 (7.5%) tablets/ capsules. Herbal drugs were identified as cannabis; no further analysis performed and there is the potential that these products may have contained synthetic Downloaded from by guest on December 29, 2014 the most common drugs used were cannabis (6.9%), powder cocaine (2.2%) and ecstasy (1.4%).1 Subpopulation analysis of those who frequent the nighttime economy,7–9 have shown that nearly one-third (30.7%) of those who visit nightclubs four or more times in the past month have used drugs in the past year compared with 6.5% of their peers who do not visit nightclubs.1 In this higher drug-using group, the pattern of use is also different to the general population, with a higher proportion using ecstasy, mephedrone and LSD.7,10 Self-reported surveys however are not without limitations. Recreational drugs are often adulterated with other drugs or chemicals to enhance the desired effects or to mimic the appearance of the drugs.11–16 For the drug user, this can be a source of potential harm due to an increase in adverse effects directly from the adulterant or its interactions with the drug. This variation may limit the validity of self-reported surveys as users are recalling the drugs they intended to use rather than what they actually used.11–13 In addition, drug use can be stigmatized in society and this may influence survey response as respondents may fear self-incrimination despite guarantees of anonymity.4 Methods such as audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (CASI), which eliminates some bias associated with face-to-face interviews, have been shown to achieve higher frequency of self-reporting on drug use14 but this requires additional resources and therefore cannot be carried out as easily when compared with more traditional survey methods. Validity testing by way of biological sampling has been used to check the accuracy of self-reporting and this has shown that self-reporting alone is not a good way to measure drug use.4 However, biological assays can be liable to producing false results (most commonly falsenegative) depending on type of sample, collection device and time elapsed from drug consumption15 and may themselves require confirmatory assays. A different way to assess trends in drug use is through the analysis of drugs in circulation by collecting them in drug amnesty bins.16–18 Work by our group established this technique and more recently a protocol has been published by the London Drug & Alcohol Policy Forum.19 In addition to this analysis, amnesty bins also: (i) provide a safe place for security staff to dispose of any substances they find; (ii) decrease drugs entering premises; (iii) advertise that venues do not tolerate the use of drugs; (iv) allow clubbers to dispose of drugs without fear of arrest; and (v) provide a secure method of storing potentially controlled drugs/substances before collection/disposal by the correct authorities.19 This study looked at the trends in local recreational drug use by analysing contents of amnesty Trends in recreational drug use gay dance clubs 1113 Sealed Police Evidence Bags Tablet/ Capsule Liquid Herbal Powder Idenfied on database? Liquid idenfied Cannabis Infrared spectroscopy No Unidenfiable Tablet/ Capsule idenfied GC-MS GC-MS Perform Marquis Test for confirmaon Tablet idenfied Powder idenfied Powder idenfied Figure 1. Flow diagram of the analysis of samples using the Home Office Licence method protocol. cannabinoid receptor agonists. The remaining items were analysed for further identification (Figure 2). Liquids These were colourless or pale yellow and contained in a variety of packaging ranging from brown medicinal dropper bottles to nail polish remover pads. Analysis found gamma-butyrolactone (GBL) in 66.7% (n = 160) of the samples and ‘poppers’ (alkyl nitrites) in 30.0% (n = 72). The remaining 3.3% (n = 8) of the samples were found only to contain water or aqueous solutions. None of the liquids contained gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB). Powders Powders provided the widest range of drugs, including novel psychoactive substances (NPS), with mephedrone being the most common (n = 105, 47.7% of total powder items). Other drugs were ketamine (n = 28, 12.7%), 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine (MDMA) (n = 26, 11.8%), cocaine (n = 21, 9.5%), methylamphetamine (n = 6, 2.7%), para-methoxy-N-methylamphetamine (PMMA) (n = 3, 1.4%), 4-methylethcathinone (4-MEC) (n = 3, 1.4%), piperazines (n = 2, 0.9%) [N-benzylpiperazine (BZP) and 3-trifluoromethylphenylpiperazine (TFMPP)], amphetamine (n = 2, 0.9%) and 5-iodo-2-aminoindane (5-IAI) (n = 1, 0.5%). The remaining 10.5% of samples (n = 23) contained no recreational drug or novel psychoactive substance. Instead these were medicinal drugs including caffeine, ibuprofen, acetaminophen, chloroquine or substances such as lactose and calcium carbonate which were presumably intended to mimic the appearance of other drugs. Tablets and capsules Both medicinal and recreational drugs were found in the tablets and capsules. Medicinal drugs (43.9% of tablets), of which there were 14 different types (Table 1), included two sildenafil tablets which could have potential use as a recreational drug. A further 12.2% contained plaster of Paris (calcium sulphate dihydrate). It is likely that this was intended to mimic the appearance of ‘ecstasy’ tablets. The remaining samples were MDMA (n = 8, 19.5%), TFMPP (n = 4, 9.8%), benzodiazepines (n = 1, Downloaded from by guest on December 29, 2014 Yes 1114 T. Yamamoto et al. GBL 160 Mephedrone 105 Alkyl Nitrites 72 Herbal/Cannabis 43 MDMA 34 Medicinal drugs 30 Ketamine 28 Cocaine 21 Plaster of Paris 8 Aqueous Soluon 8 Methylamphetamine 6 Piperazines 6 Caffeine 6 Other 6 3 3 Amphetamine 2 Benzodiazepine 1 6-APB 1 5-IAI 1 Figure 2. Graph showing the types of samples collected in the amnesty bin. Table 1 Different types of pharmaceutical drugs found in the tablets Drug Numbers found Paracetamol Sildenafil citrate Ibuprofen Atripla Nicotinamide Truvada Nicardipine Hydrochloride Detrusitol (Tolterodine) Viramune (Nevirapine) Folic acid Imirpamine Ferrous sulphate Tramadol Co-fluampicil 3 2 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2.4%) and 5/6-(2-aminopropyl)benzofuran (5/6APB) (n = 1, 2.4%). Five samples had a physical appearance not previously been seen and were added to the TICTAC drugs identification database; these were MDMA (2 samples), combination of TFMPP/BZP (1), 5/6-APB (1) and plaster of Paris (1). Discussion This study provides further evidence that drug use is common amongst those attending nightclubs. The gay community is often seen as early adopters of the latest trends in drugs23 and the wide variety of drugs, including numerous NPS, seen in this study reflects this. The study has found distinct differences in types of drug found when compared with the results of previous analyses of amnesty bins in 2005 and 2008.16,17 The most common form of drug found in this study was liquid, followed by powder, herbal and tablet/capsule. In past studies tablets and powders were the most common.16,17 The difference seen here is likely to be due to the high use of GBL and ‘poppers’ which are used in liquid form and are drugs favoured by the gay community. Another important difference compared with previous studies is that no GHB was detected; this is discussed in more detail below. Comparison to surveys and other local data on drug use Data collection on drug use in the local area has previously been conducted through the use of surveys, web-mapping projects and analysis of pooled Downloaded from by guest on December 29, 2014 4-MEC PMMA Trends in recreational drug use gay dance clubs 1115 Table 2 Comparison of findings from the amnesty bin samples, the results of self-reported surveys and analysis of urine from nightclub urinals Drug Amnesty Bin (%) Urinal study concentration ng/ml21 Survey 120 (%) Survey 222 (%) GBL Mephedrone Alkyl nitrites (poppers) Cannabis MDMA Ketamine Cocaine Methylamphetamine Piperazines 4-MEC PMMA Amphetamine Benzodiazepine 6-APB 5-IAI 29.4 19.3 13.2 7.9 6.3 5.1 3.9 1.1 1.1 0.6 0.6 0.4 0.2 0.2 0.2 23000 2965.1 – – 1922.9 2273.3 154.9 35.6 123.7 – – 57.7 – – – 14 27 – 15 11 14 16 3 – – – – – – – 24 41 – 14 – 13 17 – – – – – – – – Drug adulteration Drugs are often adulterated to enhance desired effects or to mimic the appearance and reduce the proportion of the active drug.26 Adulterants may include active pharmaceutical ingredients, which can have their own inherent toxicity, or pharmacologically inactive substances such as plaster of Paris which has historically been used as an adulterant in foods.27 Although substances such as plaster of Paris have no inherent toxicity, the user may take a number of these tablets/powders and not find the desired effect. This may cause the user to take the same or possibly more of the drug on the next occasion they use it; posing a risk to the user should the next batch of drugs contain a higher proportion of the active substance. Impact of legislation One notable finding was the absence of GHB amongst the samples analysed. In a study of samples seized from the same nightclubs in 2006, 37.8% of the liquid drugs were aqueous solutions of GHB with the remaining samples containing GBL.18 GHB was classified under the UK Misuse of Drugs Act, 1971 as a class C drug in June 2003. GBL which is a pro-drug of GHB was also classified as a Class C drug in December 2009, but only when intended for human consumption. It therefore remains available when used in products which are not aimed for human consumption such as nail varnish remover and other chemical products. Our study suggests that the GHB legislation has had a greater impact than the GBL legislation. Downloaded from by guest on December 29, 2014 urine from portable urinals located at the same nightclubs.23–25 These studies were held at different times, concentrating more on Friday night/weekends when clubs were at the busiest. Comparison of results from this study and these previous studies are shown in Table 2. This shows that GBL and mephedrone, which were the most common drugs found in the amnesty bins, were also the drugs of choice amongst clubbers in the surveys25 and commonly detected in the urine samples.24 However, there are also differences between the datasets, with drugs such as cocaine and ketamine found less frequently in amnesty bins ranked higher in the surveys and also found in greater concentration in urine analyses. One potential explanation for this is that users may be selectively keeping drugs they intend to use and dispose of any that are not required upon entering the club; however this would not explain the positive correlation between the sample sets for GBL and mephedrone. The ease with which drugs can be concealed and consequently not detected during a door search by nightclub security staff is also an important factor. Wraps or small ziplock plastic bags containing powder are likely to be more easily concealed than liquids. The discrepancies in results between the different datasets suggest that each method of collecting data on drug use do not always validate each other but they perhaps complement each other. Therefore, they each provide information which can in combination give a more accurate picture of drug use. Awareness of the limitations of each technique allows efficient data triangulation between the techniques. 1116 T. Yamamoto et al. Mephedrone was classified as a Class B drug in April 2010 but studies and surveys conducted nationwide after this date found ongoing evidence of mephedrone use25 despite the rising price of the drug since classification.8,28 This was also demonstrated in surveys in these nightclubs where mephedrone was the most commonly used drug on the night and also the most favoured drug.25 This study, approximately 18 months since classification, confirms that mephedrone continues to be present. New formulations of drugs Novel psychoactive substances (‘legal highs’) In recent years, there has been an emergence of a range of different NPS.5 In this study the NPS detected were 4-methylmethcathinone (mephedrone), 4-methylethcathinone (4-MEC), 5-Iodo-2-aminoindane (5-IAI) and 5/6-(2-aminopropyl)benzofuran (5/6-APB). Of these, mephedrone and 4-MEC are classified under the UK Misuse of Drugs Act, 1971. Another controlled substance para-methoxy-Nmethylamphetamine (PMMA), which was held responsible for 12 fatal intoxications in Norway31 and further outbreak of cases in Israel,32 was also found in the amnesty bin analyses. Previous studies analysing the content of such ‘legal high’ products have shown that these products can contain active ingredients which are not declared as such.33 These additional active ingredients may be other ‘legal’ substances or controlled substances such as PMMA, mephedrone and 4-MEC.34,35 The finding of controlled substances in the samples suggests that there may be a close association between the NPS and illicit markets.35 Limitations of the study Although this study removes the recall and responder bias seen in self-reported surveys, it is not without its limitations. Analysis of amnesty bin samples Conclusions The analysis of the amnesty bins of two gay-friendly nightclubs in South East London has provided a snapshot of the likely pattern of drug use in the gay community. Comparison of data from this study with previous amnesty bin studies has shown a change in the drugs—in particular a switch from GHB to GBL. Use of data from this study together with data from self-reported surveys and other studies such as the analysis of pooled urine can provide a more accurate picture of drug use. Information found from this study will be useful in designing targeted drug prevention and education and also in informing clinicians and legislative authorities. Wider use of this technique has the potential to allow comparison of drug availability/ use in different sub-populations and geographical regions. Conflict of interest: None declared. References 1. Home Office Statistical Bulletin. Drug Misuse Declared: Findings from the 2011/12 British Crime Survey for England and Wales (2nd Edition) July 2012 [online] 2012. http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/publications/science-research -statistics/research-statistics/crime-research/drugs-misuse-dec -1112/drugs-misuse-dec-1112-pdf?view=Binary (20 August 2013, date last accessed). 2. Binks S, Hoskins R, Salmon D, Benger J. Prevalence and healthcare burden of illegal drug use among emergency department patients. Emerg Med J 2005; 22:872–3. Downloaded from by guest on December 29, 2014 There has been a decrease in self-reported use of MDMA in recent years1,29 but it remains the fifth most common drug found in the amnesty bins. The TICTAC database was updated following this study with previously unseen logos on MDMA tablets to suggest the marketing of this drug is continually evolving. In addition, a powdered form of MDMA was found. This may be in response to the decreased purity of the drug in the tablet form.29 Previous studies from our group have shown significant variation in the MDMA content of MDMA tablets.30 As a consequence, there may be increased health risks as the dose ingested becomes more difficult to control when taken in a powdered form. is limited to what was discarded by the clubbers and/or found during door searches prior to entering the nightclub. It is possible that clubbers selectively discarded drugs which they did not want and kept those that they did. In addition, there were no specific measures in place to ensure consistency of the security checks performed at the door by staff which may be another source of bias. As an example, bulky drugs may be more likely to be detected than more discreet compounds. These confiscated drugs were not disposed in a separate bin and therefore it was not possible to differentiate between these and the selectively discarded drugs. It is also likely that some drugs may have been consumed prior to entry to the club and there is the potential that users may source drugs within the nightclubs. Finally, not all drugs were analysed and there is the potential, for example, that herbal products assumed to be cannabis may have contained synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists. Trends in recreational drug use gay dance clubs 3. Morgan CJA, Noronha LA, Muetzelfeldt M, Fielding A, Curran HV. Harms and benefits associated with psychoactive drugs: findings of an international survey of active drug users. J Psychopharmacol 2013; 27:497–506. 4. Harrison L. The validity of self-reported drug use in survey research: an overview and critique of research methods. NIDA Res Monogr 1997; 167:17–36. 5. European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction Annual Report 2012. http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/attache ments.cfm/att_190854_EN_TDAC12001ENC_.pdf (20 August 2013, date last accessed). 6. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World Drug Report 2012. http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-ana lysis/WDR-2012.html (7 July 2013, date last accessed). 7. The Mixmag/Guardian Drugs Survey 2012. http://www. mixmag.net/drugssurvey (20 August 2013, date last accessed). 8. Wood D, Hunter L, Measham F, Dargan PI. Limited use of novel psychoactive substances in South London nightclubs. QJM 2012; 105:959–64. 9. European Commission. Eurobarometer Special Surveys – European Week for Drug Abuse Prevention. http://ec. europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_067_en.pdf (20 August 2013, date last accessed). 11. Brandt SD, Sumnall HR, Measham F, Cole J. Analyses of second-generation ‘legal highs’ in the UK: initial findings. Drug Test Anal 2010; 2:377–82. 12. Vogels N, Brunt TM, Rigter S, van Dijk P, Vervaeke H, Niesink RJ. Content of ecstasy in the Netherlands:19932008. Addiction 2009; 104:2057–66. 13. Brunt TM, Rigter S, Hoek J, Vogels N, van Dijk P, Niesink RJ. An analysis of cocaine powder in the Netherlands: content and health hazards due to adulterants. Addiction 2009; 104:798–805. 14. Turner CF, Villarroel MA, Rogers SM, Eggleston E, Ganapathi L, Rpman AM, et al. Reducing bias in telephone survey estimates of the prevalence of drug use: a randomised trial of telephone audio-CASI. Addiction 2005; 100:1432–44. 15. Ventura M, Pichini S, Ventura R, Leal S, Zuccaro P, Pacifici R, et al. Stability of drugs of abuse in oral fluid collection devices with purpose of external quality assessment schemes. Ther Drug Monit 2009; 31:277–80. 16. Ramsey JD, Butcher MA, Murphy MF, Lee T, Johnston A, Holt DW. A new method to monitor drugs at dance venues. BMJ 2001; 323:603. 17. Kenyon SL, Ramsey JD, Lee T, Johnston A, Holt DW. Analysis for identification in amnesty bin samples from dance venues. Ther Drug Monit 2005; 27:793–98. 18. Wood DM, Warren-Gash C, Ashraf T, Greene SL, Shather Z, Trivedy C, et al. Medical and legal confusion surrounding gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB) and its precursors gammabutyrolactone (GBL) and 1,4-butanediol (1,4BD). QJM 2008; 101:23–9. 19. LADPF. Drugs at the door – Guidance for venues and staff on handling drugs. http://www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/services/ adult-health-wellbeing-and-social-care/drugs-and-alcohol/ substance-misuse-partnership/Documents/SS_LDAPF_drug satthedoor2011.pdf (20 August 2013, date last accessed). 20. TICTAC Communications Ltd, St Georges University of London, Cranmer Terrace, SW17 0RE. http://www.tictac. org.uk/ (20 August 2013, date last accessed).. 21. Winstock AR, Wolff K, Ramsey J. Ecstasy pill testing: harm minimization gone too far? Addiction 2001; 96:1139–48. 22. WHO Traditional Medicine. Definitions. www.who.int/medi cines/areas/traditional/definitions/en/index.html (20 August 2013, date last accessed). 23. Measham F, Wood DM, Dargan PI, Moore K. The rise in legal highs: prevalence and patterns in the use of illegal drugs and first- and second generation ‘legal highs’ in South London gay dance clubs. J Subs Use 2011; 16:263–72. 24. Archer JR, Dargan PI, Hudson S, Davies S, Puchnareqicz M, Kicman AT, et al. Taking the Pissoir - a novel and reliable way of knowing what drugs are being used in nightclubs. J Subs Use 2013; 00:1–5. 25. Wood DM, Measham F, Dargan PI. ‘Our favourite drug’: prevalence of use and preference for mephedrone in the London night-time economy 1 year after control. J Subs Use 2012; 17:91–7. 26. Cole C, Jones L, McVeigh J, Kicman A, Syed Q, Bellis M. Adulterants in illicit drugs: a review of empirical evidence. Drug Test Anal 2011; 3:89–96. 27. The fight against food adulteration. http://www.rsc.org/edu cation/eic/issues/2005mar/thefightagainstfoodadulteration. asp (20 August 2013, date last accessed). 28. Winstock A, Mitcheson L, Marsden J. Mephedrone: still available and twice the price. The Lancet 2010; 376:1537. 29. Smith Z, Moore K, Measham F. MDMA powder, pills and crystal: the persistence of ecstasy and the poverty of policy. Drugs and Alcohol Today 2009; 9:13–19. 30. Wood DM, Stribley V, Dargan PI, Davies S, Holt DW, Ramsey J. Variability in the 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine content of ‘ecstasy’ tablets in the UK. Emerg Med J 2011; 28:764–5. 31. Vevelstad M, Oiestad EL, Middelkoop G, Hasvold I, Lilleng P, Delaveris GJ. The PMMA epidemic in Norway: comparison of fatal and non-fatal intoxications. Forensic Sci Int 2012; 219:151–7. 32. Lurie Y, Gopher A, Lavon O, Almog S, Sulimani L, Bentur Y. Severe paramethoxymethamphetaine (PMMA) and paramethoxyamphetamine (PMA) outbreak in Israel. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2012; 50:39–43. 33. Elie MP, Elie LE, Baron MG. Keeping pace with NPS releases: fast GC-MS screening of legal high products. Drug Test Anal 2013; doi:10.1002/dta.1434 [Epub 7 January 2013]. 34. EMCDDA-Europol 2011 Annual Report on the implementation of Council Decision 2005/387/JHA. http://www. emcdda.europa.eu/publications/implementation-reports/ 2011 (20 August 2013, date last accessed). 35. Ayres TC, Bond JW. A chemical analysis examining the pharmacology of novel psychoactive substances freely available over the internet and their impact on public (ill) health. Legal highs or illegal highs? BMJ Open 2012; 2:e000977. Downloaded from by guest on December 29, 2014 10. Wood DM, Davies S, Calapis A, Ramsey J, Dargan PI. Novel drugs—novel branding. QJM 2012; 105:1125–6. 1117

© Copyright 2025