Document 67791

Irish National Teachers' Organisation

Early Childhood

Education

Report of a Seminar

.Pubiished by the Irish National Teachers' Organisation.

35 Parnell Square, Dublin 1,

©

INTO. 7983

Origination by Healyset. Dublin 1.

Printed by Oval Printing Company, Dublin 7.

Contents

Page

Introduction

4

Trends in early childhood education

5

Thomas Kel/aghan

Education and the phychological and physical

development of young children

23

Anne T. McKenna

Education for young children:

infant classes in primary schools

35

Siobhtm M. Hurley

Early education for children with special needs

47

Anne O'Sul/ivan

Home and school in the education of the young child

57

Elizabeth McGovern

Preschools, playschools, nursery schools and classes

69

Kathleen Day

Appendix

78

Introduction

In August 1981 the then Minister for Education, Mr. John

Boland TD, decided to raise the age of entry to primary schools and

thereby he initiated, albeit inadvertently, a public debate about

early childhood education.

The Executive Committee of the Irish National Teachers'

Organisation decided, as part of its contribution to the debate, to

hold a seminar on this important educational and social problem.

The seminar, which was held in Mary Immaculate College of

Education in Limerick in June 1982, was attended by more than

150 people.

The participants heard an interesting and stimulating series of

lectures and contributed to the success of the seminar through

their involvement in group discussions on various aspects of the

central theme.

This report contains the text of the lectures delivered at the

seminar. It is intended to publish separately a supplement giving a

summary of the group discussions.

The Executive Committee would like to record its appreciation

and gratitude to all those who contributed to the success of the

seminar and in particular to the lecturers, chairpersons and

rapporteurs and to the Principal and staff of Mary Immaculate

College of Education.

E. G. Quigley,

General Secretary

February, 1983

Trends in early childhood education

Thomas Kellaghan

Director, Educational Research Centre

St. Patrick's College, Dublin

The author is indebted to Mary Campbell for assistance in the preparation of

this paper.

The care and, in the broadest sense, the education of the young is,

and always was, one of the most basic of human tasks. On it depends

not only the survival of individuals but the survival of the race.

Further, differences in style and practice in child care seem to affect

the psychological characteristics of children throughout their lives as

well as the characteristics of the society of which they form a part.

Almost invariably across all societies, the care of the infant during the

first year or two of its life is primarily the responsibility of its mother.

After that, practice varies and other individuals or institutions may

begin to take over some aspects ofthe care and education of the child.

In many countries in western society, there has been an increase in

recent years in the availability of resources outside the home to assist

in the early phases of the education of children. This can be seen in

general terms as an extension of national educational enterprises

which began in the last century and have been steadily expanding

ever since, though there are also more specific reasons for the

intense interest in early childhood education and the expansion of

facilities which were features of the 1970s (ct. European Economic

Community, 1979; van der Eyken, 1982; Woodhead, 1979).

The tasks facing the child in the first five or six years of its life are not

inconsiderable and the accomplishments of the vast majority of

children during these years are impressive. However, the

achievements of some are not satisfactory and when we consider the

range of tasks facing the child, that is hardly surprising. These tasks

include meeting organic needs and establishing routine habits (such

as eating, sleeping, and washing): learning motor skills and

5

associated confidences (such as walking, running, and climbing):

developing manipulatory skills (building with blocks, beads, tying

things, buttoning one's coat); learning control and restraints

(listening to stories, sitting still); developing social behaviour (sharing

with others, developing appropriate dependent and independent

behaviour); emotional development (coping with fear, aggression,

anger, frustration, guilt; psycho-sexual development (identification,

sex-role learning); language development; and intellectual

development covering a broad spectrum of activities from preceptual

discrimination to concept formation (Sears' Dowley, 1963).

Despite the fact that early child development has become a major

focus of attention and policy formation in recent years many people

still seem uncertain about the role of educational provision in aiding

that development. There has, for example, been a cut-back in

preschool provision for disadvantaged children in the United States.

In this country, as recently as 1979, a former secretary of the

Department of Education claimed that some teachers would regard

four-year old entrance to school as 'an extravangantly costly babysitting service' (0 Conchobhair, 1979), while more recent

government decisions about the age of entry to school must at least

raise questions about the understanding of and commitment to early

childhood education among teachers, politicians, and administrators.

These statements and actions suggest that the value of early

childhood education is not universally accepted. Indeed not only in

this country, but throughout the world, education at this level ranks

below elementary, secondary, and third-level education in priority(cf.

Psacharopoulos, 1980). And yet, a number of changes and

developments in recent years has ensured that politicians,

administrators, and educators can no longer afford to ignore the area

of early childhood education. Some of these changes and

developments have occurred in the family and in society; others are

the result of a renewed interest in the study of early development.

Among changing family conditions is an increase in the number of

single-parent families and of mothers working outside the home,

either for economic reasons or for personal fulfilment. Thus the major

caretaker is no longer available in many families on a full-time basis to

look after the young child. Further, other adults (grandparents, aunts)

who often formed an extended family are becoming less a feature of

the family circle, particularly in urban areas. Households are getting

smaller and there are fewer people to share in looking after young

children (Hunt, 1970). This is happening at a time when there is

growing appreciation of the importance of the early childhood years

for the development of the child.

Emphasis on the importance of early childhood is not of course

new; the early experiences of the child have been regarded as crucial

in theories of child development, particularly ones relating to

personality. What is new is the attempt to translate into educational

practice on an extensive scale the belief that environmental factors

6

exercise considerable influence on the development of perceptual

and higher cognitive skills in children before the age of five. Such

educational practice is also supported by the belief that if certain

aspects of development do not take place at a certain time, they may

not take place at all or at least later development will be seriously

impaired.

Much of the rationale for these views has its basis in the work of

Donald Hebb and his colleagues at McGill University which was

carried out in the 1 940s and 1950s. A series of experimental studies

with animals (rats, dogs, and chimpanzees) examined the effect of

deprivation on perceptual skills and on 'intelligence' or problemsolving ability. In general, the studies indicated that the performance

of animals that had been deprived of certain types of experience early

in life was seriously impaired at a later date. On the 'basis of such

studies, Hebb (1949) argued that a great deal of perceptual learning is

necessary before we see the world as the normal adult sees it. For

example, he disputed the view, associated with Gestalt psychology,

that the human infant immediately perceives a square shape as a

unified structure or whole. By his second year, the child may do so, but

this is the result of a vast number of visual experiences and muscular

explorations, and it is in the combinafion of these that a shape gets its

consistent structure.

The popularization of this work in the writings of Bruner (1961) and

Hunt (1961), received considerable attention. Interpreting the work,

Bruner (1961) concluded that an environment that is impoverished

(that is, one that is monotonous with limited opportunities for

different kinds of stimulation, discrimination, and manipulation)

'produces an adult organism with reduced abilities to discriminate,

with stunted strategies for coping with roundabout solutions, with

less taste for exploratory behaviour, and with a notably reduced

tendency to draw inferences that serve to cement the disparate

events of its environment' (p. 199).

Around the same time, the importance of early childhood received

further support in Bloom's (1964) conclusions following reanalysis of

data collected in longitudinal studies of the development of children.

His finding that scores on intelligence tests at the age of five or six

correlated highly with scores at the age of 171ed him to conclude that

a considerable amount of intellectual development took place in the

preschool years and that the pattern for later development was well

established by the time the child began formal schooling.

All this might have remained of academic interest only and might

have had little impact on educational practice if it had not happened at

a time when Americans were looking critically at the performance of

their schools and particularly at the role of schools in dealing with

problems of poverty. Concern was being expressed at the poor

attainment and early drop-out of children from low socio-economic

status homes and the possible loss of talent which this involved. This

concern seemed to fit in well with another dominant theme of the

7

1960s - that of equality of opportunity. For a number of reasons,

educational reform was perceived as the main avenue through which

more general social reform could be attained (Madaus, Airasian, &

Kellaghan, 1980).

The United States Congress turned to 'compensatory' preschool

education as the major means of attaining equality. This appro\lch

was predicated in part on the belief that since intelligence was

malleable in the preschool years, education could have a large impact

if children from disadvantaged backgrounds were 'treated' early in

their educational careers. The now well-known Head Start

programme, designed to provide health, nutritional, day-care, and

educational services, set out to overcome the educational

deficiencies which children from poor backgrounds manifested when

beginning school by providing preschool experiences for these

children. It was believed, and this reflects long-cherished American

beliefs about the utility of schooling, that children from 'high-risk'

families, if they were given the resources and the opportunities,

would succeed in school and as adults in later life. This early

education was seen as being a major factor in breaking the cycle of

underachievement and poverty in American society. In this, a

tradition in the use of early childhood education as an instrument of

progressive reform was revived. In attempts to deal with problems

caused by industrialization and urbanization towards the end of the

last century, preschool programmes were established in all major

American cities, first on a voluntary basis and later under public

sponsorship (Lazerson, 1972). The crusade of the 1960s looked like a

revival of the efforts of the 1890s, but on a grander scale.

However, the roots of early childhood education outside the home

are to be found in Europe, not in America. In tracing those roots, one is

brought back to pioneers in the championing of children'S rights, such

as Comenius (1592-1670) and Rousseau (1712-1778), whose

writings did much to promote the concept of childhood and rights of

children. Early childhood education in a communal setting actually

took form mainly through the efforts of Froebel (1782-1852) and, at a

later stage, those of Montessori and the McMillan sisters. The

systems they established flourished throughout this century and,

despite a number of challenges, still exercise considerable influence

today (cf. Weber, 1971).

Here we may pause briefly to consider some of the nomenclature

that has emerged from early childhood education movements. A large

variety of terms has, and still is, being used to describe institutions

which cater for early childhood education. We cannot hope to sort out

fully the meanings ofthese terms which sometimes vary from country

to country or over time in their meaning. Further, anyone term can be

used to describe institutions in which a variety of educational

practices may flourish. Since a good deal of early childhood education

has been and continues to be carried out on a voluntary basis, it is not

surprising that there is a lack of uniformity in terminology.

8

Some of the terms which are used to describe educational facilities

up to about the age of six are playschool, day nursery, daycare centre

or group daycare, family daycare, creche, nursery school, nursery

class, academic preschool, shared-rearing preschool, kindergarten,

and infant school. Some of the terms emphasize a caring or custodial

function. Much daycare (family daycare) takes place in the child's own

home with hired minders. In other cases, institutional arrangements

are provided. Daycare was the term given to facilities designed to

'warehouse' children in the United States while their mothers worked

during the second world war. On the other hand, the term academic

preschool suggests a serious educational function and such

institutions are often a downward extension of the primary school and

may focus on the development of 'school readiness' skills. What goes

on in a nursery school is not immediately obvious from ttie name, It is

a term particularly associated with English education and has been

used to describe facilities for children around the ages ofthree orfour.

The first kindergarten was established in 1837 by Froebel, who

rejected terms which used the word school, such as infant school and

nursery school (Lawrence, 1952); he selected the work kindergarten

because it embodied his view of child development as something

reflecting the development of plants in a garden. What goes on in an

infant sChool is not immediately obvious from its name either. The one

thing you will not normally find insuch a school is an infant, The first

infant school has been attributed to Robert Owen (established in

1816) and in a number of ways its activities reflected the Froebel

philosophy of child development. Both kindergarten and infant school

are often used to describe facilities for children who have completed

nursery-school or who are in the junior grades of primary school.

In this paper when we talk about early childhood education, we will

for the most part be talking about arrangements in a group setting

away from the child's home that are made for children under the

statutory school-entry age. Further, our concern will be more with

provision for older children (between the age of three and the age of

compulsory schooling) than with provision for younger children,

though some consideration will have to be given to the latter since in

some countries a distinction is not made between the two kinds of

provision. In the case of Ireland, we shall be talking about children

who are in schools which also cater for older children: mainly, we

shall be concerne.d with children who are in what are called junior and

senior infant classes. In other countries, the facilities for children of

this age are often separated from those for older children.

Our consideration will focus more on publicly provided facilities

than on privately provided ones. Many early childhood facilities,

especially those for young children, are private and not a great deal is

known about them. It is difficult to obtain accurate information on the

nature or extent of such faCilities or on the numbers of children who

participate in them. In the official statistics supplied for participation

for some countries, it is not always clear whether they include

children attending private as well as public institutions.

9

Models of early childhood education

Of greater importance than the labels one might attach to early

childhood education are the characteristics of that education. In

keeping with the multiplicity of labels that exist. one also finds a

multiplicity of institutional arrangements and practices. Not only does

one find a great variety in the preschool provision that exists

throughout the world, one finds variety even within individual

countries. A major attempt to categorize systems of provision

throughout the industrialized world has been made by Robinson,

Robinson, Darling, & Holm (1979) who have described the features of

a Latin-European model (particularly as exemplified in France and

Belgium), a Scandinavian model, a Socialist model (particularly as

exemplified in the Soviet Union), and an Anglo-Saxon model (as found

in the United States, Britain, and Canada). While the categorization is

not entirely satisfactory, we may take it as a basis for considering a

number of dimensions along which approaches to early childhood

education vary. A consideration of these dimensions will provide

some feel forthe range of philosophies and practices which operate in

this area of education.

Vertical organization

First we may note that in many courtries an organizational

distinction is made between facilities provided for children up to the

age of two and a half or three, in what Robinson et al (1979) call

creches, and facilities provided for children from that age upto the age

of compulsory schooling, which may vary between five (in the United

Kingdom) and seven (in Denmark); the latter facilities are called

kindergartens by Robinson at al. The Scandinavian countries do not

have this distinction. They have a unified system of preschool

education from the age of six months to seven years. There is also a

. trend in the Soviet Union to move to a unified 'nursery-kindergarten'

system; the reason given is that in separate facilities, there is too

much emphasis on physical care to the exclusion of the cognitive,

social, and emotional development of the children.

National policies for families

The national policy for families in a country can have important

implications for the provision of early education facilities, particularly

for who provides it, who controls what goes on in the schools or

centres, and what role is assigned to parents. In the matter of family

policy, a distinction may be drawn between Socialist and

Scandinavian countries on the one hand and Anglo-Saxon ones on

the other, with the Latin countries somewhere in between. In the

Socialist and Scandinavian countries, child rearing is seen as

something to be shared by family and state. In the Anglo-Saxon

countries, child rearing is primarily a family function. which in certain

circumstances may be aided by the state. Bronfenbrenner (1970) has

10

drawn the distinction sharply in his discussion of upbringing in the

Soviet Union and the United States. While the Soviet system

recognizes that parents have a.uthority, this authority is only a

reflection of that of the state. Such a position would not generally be

accepted in the Anglo-Saxon world. In this context the provisions of

Article 42 of the Irish Constitution come to mind; the article

recognizes 'the primary and natural educator of the child' to be the

family and the state 'guarantees to respect the inalienable right and

duty of parents to provide ... for ... the education of their children'.

Parents are free to provide education 'in their homes or in private

schools recognized or established by the state'. While the

Constitution grants to parents the primary moral and legal

responsibility of bringing up their children, in this country as

elsewhere, there are pressures which are making it increasingly

difficult for parents to do that. The result is a growing ·demand for

outside services, including state ones, even in countries where

traditional family policy has emphasized the primacy of parents.

Control of child care

Closely related to national family policy is the control of child care.

In general, Socia list economies are associated with standardization of

programmes while free enterprise ones tend to encourage

diversification (Peters, 1980). While tight control is exercised by the

central authorities on school curricula and there is a high degree of

uniformity in educational practice in all schools in socialist countries,

there is also some diversification. In the Soviet Union, for example,

both creches and kindergartens are sometimes run by factories,

farms, and other institutions to provide facilities for employees. In

other cases, they are run by a government ministry (Grant, 1964). In

Scandinavian and Latin countries, the central government controls

general policy, but programmes may be administered and operated

locally. France, for example, does not provide a standard curriculum

for kindergartens (teachers work with inspectors in doing this), while

in Scandinavian countries, programme guidelines are provided by the

National Board of Health and Welfare, but teachers may adapt these

to their own circumstances and needs. The least amount of central

control occurs in Anglo-Saxon countries; while sectors of early

childhood provision in these countries have some centrally organized

features, these occur in the context of considerable decentralization.

Central control is exercised by a variety of government ministries. In

Scandinavian countries, it is pxercised by Departments of Social

Affairs, Social Welfare, and Hea"n. In other countries, the tendency is

for a Ministry of Health or Welfare to exercise control over institutions

attended by children up to about the age of three, while a Ministry of

Education or Public Instruction is responsible for institutions attended

by children from the age of three onwards. In all the European

Community countries, with the exception of Denmark, the

responsibility for the education of children over the age offour, and in

11

some cases for children as young as two (France). two and a half

(Belgium), and three (Italy, United Kingdom), lies with the Ministry of

Education (European Economic Community, 1979).

Curriculum objectives and content

Perhaps the area in which there has been the greatest debate over

early childhood education has not related to its' organization or control

but to the curricula which are followed. There are two basic

dimensions along which curricula can be differentiated (Stodolsky,

1972). One relates to curriculum objectives and the second relates to

the structure of the curriculum. The major distinction that is usually

drawn regarding objectives is that between curricula or programmes

which emphasize intellectual-scholastic goals and those which

emphasize socio-emotional ones. We shall return to this distinction

later; at this point, we will look at the emphasis of the various systems

on these two sets of goals. In general, the Anglo-Saxon and

Scandinavian systems have emphasized socio-emotional

development throughout the whole period of early childhood

education. In Latin countries, health, hygiene, and socio-emotional

development are emphasized during the early years of life in creches,

while the kindergarten attends more to cognitive goals and in

particular to the preparation of children for formal schooling. The

Socialist countries seems to have adopted a more mixed approach.

From an early age, a heavy emphasis is placed on social·aspects of

development; experience in 'collective' living is provided almost from

birth so that the child will develop an awareness of the group or

collective and its needs. Attention is also paid to language

development, to some extent as a vehicle for developing social

behaviour, to cognitive growth, to creativity, and to school readiness.

Attention to the cognitive aspects of development is receiving

increasing emphasis, even with very young children.

Curriculum structure

The second dimension on which curricula and programmes may be

differentiated is structure. In a structured curriculum, the teacher

emphasizes specific goals. Further, the pursuit of those goals is

adhered to by allocating specific times for relevent activities, by

providing suitable materials, and by prescribing children's responses.

By comparison with unstructured approaches, the structured one is

more teacher-directed and more homogeneous in its activities.

Unstructured curricula are sometimes called traditional, childcentred, or discovery curricula. The child selects its own activities

rather than being directed towards a particular activity by its·teacher.

Though such curricula are often termed child-centred by comparison

with more structured approaches, they are child-centred only insofar

as the selection of activities is concerned. A structured curriculum,

though its main focus is on the content being presented to the child,

could be child-centred to the extent that thc choice of content

12

(materials and activities) is based on developmental principles and

related to individual differences between children (Kellaghan, 1977).

The highest structure in early childhood education is associated

with the Socialist model. In this model, detailed plans of activities for

children at different age levels are laid down and systematic teaching

programmes are used. A core principle ofthese programmes is the socalled regime. Each child, as Bronfenbrenner (1970) describes it. is

on a series of reinforcement schedules. The teacher or 'upbringer'

spends a specified amount of time with each child, stimulating and

training sensory-motor functions.

"For example, at the earliest age Isvels, shewill present a brightly

colored object, moving it to and fro to encourage fo(.fowing. A bit

later, the object is brought nearer and moved slowly forward to

induce the infant to move toward it. Still later, the child is

motivated to pull himself up by the barred sides of the playpen to

assume a standing position. And infants learn to stand in such

playpens not only in Moscow, but 2,000 miles away in Soviet

Asia as well" (Bronfenbrenner, 1970, p. 17).

By contrast, Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian early childhood

education (with the possible exception of Finnish education which is

moving toward the development of more structured programmes)

consists mostly of supportive, unstructured, socialization

programmes rather than structured informational ones. Such

programmes have been described as providing.

"a warm accepting atmosphere in which a child may achieve his

own maximum social and physical development, and an ordered

atmosphere in which selected equipment and activities are

offered in sufficient variety to meet each child's level of interest

and ability" (Gordon & Wilkenson, 1966, p. 48).

Early childhood education in Latin countries may be regarded as

occupying an intermediate position in structure between the Socialist

model on the one hand and the Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian

models on the other.

The kind of objectives a curriculum has and the degree of structure

associated with it are not necessarily related. For example, one could

have a highly structured curriculum designed to attain socioemotional objectives and there is some evidence in the Socialist

model of early childhood education that structure is a feature of

programmes designed to achieve a variety of objectives. In practice,

however, it is easier to prescribe a structure for programmes with

cognitive objectives and the best known examples of highly

structured curricula in the United States were concerned with

language development (Bereiter & Engelmann, 1966; Lavate"i, 1972)

and general cognitive development (Lavatelli, 1970).

13

Preparation of teachers or upbringers

There is SDme variatiDn, nDt .only acrDSS mDdels, but even within

cDuntries, in the methDds and standards emplDyed in the preparatiDn

.of teachers Dr 'upbringers' tD use the mDre general term. Even in the

SDcialist cDuntries, where .one might expect the highest level .of

prDfessiDnal training and unifDrmity, .one finds diversity. In PDland, fDr

example, .one may take either a tWD-year vDcatiDnal cDurse Dr a threeyear university CDurse, while in the SDviet UniDn, SDme take CDurses

in teacher training cDlleges and .others in specialized secDndary

SChDDls.

In the EurDpean CDmmunity, there are five cDuntries in which the

preparatiDn and status .of persDnnel wDrking in early childhDDd

educatiDn are basically the same as the preparatiDn and status .of

teachers in elementary SChDDls: France, Ireland, Italy, LuxembDurg,

and the United KingdDm. In tWD cDuntries, the preparatiDn and status

of early childhDDd educatDrs have been traditiDnally IDwer, but these

are In the prDcess .of being raised: Belgium and the Netherlands.lnthe

Federal Republic .of Germany, the teacher .of preschDDI children is

almDst equal in status and preparatiDn tD the nDrmal teacher, while

preschDDI assistants are IDwer. Only in Denmark, amDng E.E.C.

cDuntries, is the preparatiDn and status .of the teacher .of preschDDI

children definitely IDwer (Elvin, 1981; European ECDnDmic CDmmunity, 1979).

Participation

Finally in IODking at vanatlOn in early childhoDd educatiDn

provisiDn, we may cDnsider participatiDn. MDSt Dfthe figures we have

relate tD E.E.C. cDuntries. BefDre cDnsidering these figures, we may

nDte that participatiDn even in SDcialist cDuntries is nDt particularly

high. FDr example, it is estimated that abDut 10% .of children between

six weeks and three years attend creches in the U.S.S.R. while abDut

50% between the ages .of three and seven years attend kindergarten.

The figures fDr the U.S.A. are nDt very dissimilar. Asmaller prDpDrtiDn

attend creches while the figure fDr children aged three tD six years

attending kindergarten is abDut the same (50%) as in Russia

(RDbinsDn et aI, 1979).

AmDng E.E.C. cDuntries the highest participatiDn rates are tD be

fDund in Belgium, France, LuxembDurg, and the Netherlands. FDr

example, 90% .of three-year Dlds and 97% .of fDur-year Dlds attend a

preschDDI in ~rllgium. Practically all fDur-year Dlds attend such an

establishment in France (97%). LuxembDurg (93%). and the

Netherlands (93%). LDwest participatiDn rates are fDund fDr the

United KingdDm (40% .of fDur-year Dlds, but all five-year Dlds) and

Denmark (60% .of five and six-year Dlds,). In Ireland. 65% .of fDur-year

Dlds and 95% .of five-year Dlds attend primary SChDDI (EurDpean

ECDnDmic CDmmunity, 1979).

14

Controversy on objectives and structure of

early childhood education.

Controversy on content and structure has been a feature of early

childhood education for a long time. A search for its roots brings us

back to two basically different traditions and sets of assumptions

regarding the nature of childhood and of development. One is the

Enlightenment tradition which regards education as the path to

righteousness and rationality. If one accepts this view, then an

emphasis on school-related skills and preparation for life is indicated.

The other tradition is the Romantic one which views childhood as a

period that is important in its own right and not just as a preparation

for adulthood; further, children are naturally good and their instincts,

emotions, and feelings should be allowed full expression: Given this

view of childhood, educational provision should avoid imposing on the

child objectives and structures, particularly ones of a cognitive

nature.

Rousseau (1712-1778). who applied the Romantic ideas to

education, postulated that development is made up of a series of

internally regulated stages which are transformed one into another. It

follows a regular order based on maturation and external influences

should not be allowed to interfere with it. In applying these beliefs to

educational practice, the pioneers of early childhood education,

Pestalozzi (1746-1827) and Froebel (1782-1852), stressed the

importance of the child's own contribution to development and to the

need to provide a noncoercive environment in which development

could take place in a natural way.

Towards the end of the last century and into the beginning of the

present one, a debate on the objectives and teaching approaches in

preschools took place which was very similar to the debate of the

1960s and 1970s on the same issues (Evans, 1975). For most of this

century, Dewey's views prevailed and the practice of American and

English early childhood education emphasized social and emotional

development in an informal unstructured environment. Even

Froebel's approach was regarded as too formal and structured and as

failing to provide for the child's individuality. While Montessori's

philosophy and methods were more in tune with the nondirective

influences which were favoured inAmerican classrooms, they did not

support America's commitment to play, imagination, creativity, and

self-expression, or to the importance of socialization and group

activities (Lazerson, 1972).

Dewey's position received support from Arnold Gesell whose

theory of maturation, like that of Rousseau, emphasized the role of

internal regulatory mechanisms on development. Gesell's work on

developmental characteristics suggested a more or less consistent

pattern in all children duri ng the first five years. Differences in growth

between children were attributed to original capacity, rate, or tempo,

15

and to patterns of developmental organization. Environmental factors

could support, inflect, and modify development, but they did not

generate the progress of development (cf. Gesell, Amatruda, Castner,

& Thompson, 1939). These views became known to vast numbers of

people throughout the world through the writings of Benjamin Spock.

An important educational concept in Gesell's developmental theory

was that of readiness. A child will walk when his muscles have

matured sufficiently to allow him to do so and similarly he will read

when the relevant perceptual and motor abilities have matured. Much

educational practice with young children was based on the concept of

readiness. Readiness tests were often administered to determine

whether or not reading should be taught. Trying to push development,

it was thought, would at best do no good and at worst might do harm. If

readiness is something determined by the child's intrinsic rate of

development, then academic pressure would add 'burdensome

pressures upon the child' at a time when the preschool should be

fostering self-expression and creativity (Butler, 1970).

'Another feature of traditional early childhood education practice

was the relatively little attention that was paid to cognitive

development. While this aspect of growth was not completely ignored

and while in some programmes language development received

considerable attention, the main thrust of most nursery schools was

on the social and emotional development of children. Further, most

nursery school teachers preferred a curriculum based largely on

children's own choice of activity ratherthan one that was planned and

structured by the teacher (Taylor, Exon, & Holley, 1972).

Gesell's maturational theory and the tradition in early childhood

education which it supported had considerable appeal. It fitted into a

well-defined tradition of human development, associated with names

such as Rousseau, Darwin, and G. Stanley Hall, and there was

empirical evidence to support some aspects of it. There were a

number of problems associated with it in practice, however. One was

that children were not always learning when the maturationalists

said they should be readyto(Goodlad, Klein, Novotney, 1973) andthis

became particularly obvious when educational and political attention

was focussed on children living in disadvantaged areas in the 1960s.

Another problem was that where good environmental conditions

prevailed in the homes of children, one might not be over-concerned

about the relative contributions of environmental and maturational

factors to development but where environmental conditions were not

good and children on entering school at the age of five or six were

already considerably behind their peers in scholastic skills, one had to

give further thought to the role of those environmental factors and the

possibilities of preventive action.

The reaction to the role of the traditional nursery school in helping

children from disadvantaged backgrounds meet the requirements of

school was perhaps most forcibly put in recent years by Bereiter &

Englemann 11966). They argued that the traditional nursery school

16

was not suitable for the disadvantaged because most aspects of such

schools complemented the activities of middle-class homes and

indeed in ways resembled the activities of a lower-class environment.

(For example, the middle class home is rich in verbal experience, the

nursery school, like the lower-class home, stresses seeing and doing.)

What is needed in the preschool for the disadvantaged are activities

that complement the activities of the disadvantaged home and are

similar to those of middle-class homes. Further, there is little time in

which to help the disadvantaged catch up with the privileged; hence

an intensive and selective scheme is required. In the Bereiter &

Engelmann approach, the focus is strictly on academic objectives.

Since the disadvantaged child's major deficiency is seen to be a

language one, a programme designed to teach 'middly-class

language' is provided.

'

Bereiter & Engelm'ann were not the only commentators to draw a

sharp distinction between the objectives and practices of traditional

nursery schools or 'shared rearing preschools' and academic

preschools. The former were interpreted as providing basic support

services to mothers in the rearing of their children during the

preschool years in 'a secure benign environment that is compatible

with the interests and predispositions of the young child' (Blank,

1974), while the latter were seen to be primarily concerned with the

preparation of children for the tasks of formal schooling.

No doubt this distinction is exaggerated to point up differences in

emphasis between approaches to early childhood education - one

non-structured, stressing social and emotional development, the

other highly structured with an emphasis on cognitive development.

In practice, one suspects that many preschool educational

programmes attend to a range of objectives and involve some degree

of structure. But the distinction has been of value iffor no other reason

than that it forced people involved in early childhood education to

examine some of the assumptions on which their practice was based.

We have, of course, as well as philosophical and practical positions

about child development, a growing area of empirical knowledge

about such development and about early childhood education (ct.

McKenna, 1979). Models of child development have attended to both

cognitive aspects and socio-emotional ones. The former owe much to

Piaget's work and have tended to adopt a general structural and

model-building view of development (Kamii, 1972; Kellaghan, 1977;

Kohlberg, 1968; Lavatelli, 1970; Sigel, 1972; Weikart, Rogers,

Adcock, & McClelland, 1971). Their influence has been greater in the

field of early childhood education than have approaches which have

emphasized socio-emotional development. However, psychological

approaches which give greater recognition to the role of socioemotional factors in development have also found applic~tion in early

childhood education programmes. For example, a d6velopmental

approach, drawing both on the psychological work of Erikson and

Werner and the progressive education movement. has been

17

developed at the Bank Street College of Education (Biber, 1977). This

approach has stressed the importance of the development of 'a sense

of trustfulness in others and trustworthiness in one's self; a sense of

autonomy through making choices and exercising control; a sense of

initiative expressed in a variety of making, doing, and play activities in

cooperation with others and in an imagined projection of the adult sex

role' (Franklin & Biber, 1977, p.18).

Whatever philosophical or practical position one adopts, empirical

knowledge on child development can hardly be ignored by the

practicioner or poicy maker in the field of education. This knowledge

makes the practice of preschool education at the same time easier

and more difficult. It makes it easier in that clearer guidelines are now

available about the needs and capabilities of individual children and

about programme content and structure. And it makes it more difficult

in the diagnosis of children's needs and capabilities and the provision

of appropriate educational experience is emerging as a highly skilled

professional task, requiring considerable knowledge and experience

on the part of the teacher (cf. Tamburrini, 1982).

In general, it seems that a wide range of objectives is helpful in the

practice of early childhood education, if for no other reason than that a

wide range of activities seem important for development (Kohlberg,

1968); many commentators today stress the need for eclectic and

wide-ranging curricula (Kamii 1972; Robison & Spodek, 1965;

Tamburrini, 1982). It also seems that at least for children from

disadvantaged backgrounds, some degree of structure helps

cognitive development, though peperhaps even more important than

structure is a greater understanding of child development by teachers

and a more coherent rationale on which to build a systematic

approach to their work.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we may note that recent trends in early childhood

education have been the products of a variety of interests and points

of views - national policies regarding the role and pre-eminence of

the family in child-rearing, the backgrou nd and preferences of staff of

educational and child-care institutions, and the points of view of the

sciences as interpreted and expressed by those professionally

concerned with education (cf. Luscher, 1981). The kinds of facilities

that are provided and the services that are offered reflect differences

in these points of view and interests.

The increase in resources for early childhood education which has

been a feature of many countries in recent years has been due in part

to the concern of bureaucratic organizations implementinc; publically

legitimated norms and objectives. The principle of equality of

opportunity, particularly as applied to the problems of children in

disadvantaged areas, has been the guiding m'A;ve in the provision of

18

early childhood education facilities in most countries in Western

Europe and in North America. Indeed, most of the public provision of

recent years has been directed to children from lower socio-economic

groups. Parents from this background have been more reluctant to

have their children participate in formal early childhood education

than have parents from higher socio-economic groups, a pattern that

is repeated throughout the educational system.

The interests of the family have also contributed to the expansion of

facilities. Of particular importance has been the changing structure of

the family and the increasing demands being made on it in

industrialized urbanized societies. While parents will normally show

considerable concern for their children's welfare, at the same time,

they will also have their own interests in mind, which may not always

coincide with those of their children.

Over the last twenty years, there has been considerable activityin

the study of child development which has had a marked influence on

the practice of early childhood education. We have seen something of

this when considering the objectives and structure of educational

programmes. While the practitioner may be confused by differences

in approach to the description and understanding of child

development, a knowledge of these approaches can add a rationale

and richness to the practical work of education. The good practitioner

will be sensitized to the issues involved and will select the

implications of the models that seem most appropriate for the

situation in which he or she finds himself or herself.

It is of course the interests and point-of-view of the child which

should be central to the practice of early childhood education.

Unfortunately these present problems in interpretation since the

young child is not very well able to articulate his or her interests.

Given this situation it is important that we take more time than

perhaps we have in the past to decipher those interests as best we

can. It is also important that other constituents in the area of early

childhood education, whether they be parents, teachers, bureaucrats,

or politicians, in putting forward their own claims, Should always do

so with an awareness and consciousness of those of the child, no

matter how poorly these might be articulated. For while early

childhood education may serve several interests and constituents,

and legitimately so, it can only be said to be serving its primary

function when the interests of children are regarded as paramount.

References

BEREITER,

c ..

& ENGELMANN. S. Teaching disadvantaged children in the

preschool. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. 1966.

BIBER. B. The developmental-interaction point of view: Bank Street College of

Education. In M.e. Day &R. Parker rEds.). The preschool in action: Exploring early

childhood programs (2nd ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. 1977.

19

BLANK. M. Preschool and/or education: A comment. In B. Tizard (Ed.), Early

childhood education. A review and discussion of research in Britain. Slough,

Berks: NFER Publishing Co .• 1974.

BLOOM. B.S. Stability and change in human characteristics. New York: Wiley,

1964.

BRONFENBRENNER. U. Two worlds of childhood. U.S. and U.S.S.R. New York:

Russell Sage Foundation, 1970.

BRUNER, J.5. The cognitive consequences of early sensory deprivation. In P.

Solomon et al (Eds.), Sensory deprivation. A symposium held at Harvard Medical

School. Cambridge. Mass: Harvard University Press, 1961.

BUTLER, A.L. Current research in early childhood education: A compilation and

analysis for program planners. Washington, D. c.: American Association of

Elementary~Kindergarten~Nursery Educators, National Education Association,

1970.

ELVIN, L. (Ed.). The educational systems in the European Community: A guide.

Windsor, Berks.: NFER-Nelsan Publishing Co.• 1981.

EUROPEAN ECONOMIC COMMUNITY. COMMISSION OF. Pre-school

education in the European Community. Studies Collection: Education Series No.

12. Brussels: Author, 1979.

EVANS, E.D. Contemporary influences in early childhood education (2nded.). New

York: Holt. Rinehart & Winston, 1975.

FRANKLIN, M.B .• & BIBER, B. Psychological perspectives and early childhood

education: Same relations between theory and practice. In L. G. Katz (Ed.), Current

topics in early childhood education. Vol. 1. Norwood New Jersey: Ablex Publishing

Corporation. 1977.

GESELL. A.L.. AMATRUDA. C.S .. CASTNER. B.M .. & THOMPSON. H.

Biographies of child development: The mental' growth careers of eighty-four

infants and children. A ten-year study. New York: Hoeber. 1939.

GOODLAD. J.I.. KLEIN. M.F .. & NOVOTNEY. J.M. Early schooling inthe United

States. New York: McGraw Hill. 1973.

GORDON. E.W .. & WILKENSON. D.A. Compensatory education for the

disadvantaged. Programs and practices. Preschool through college. New York:

College Entrance Examinations Board 1966.

GRANT, N. Soviet education. Harmondsworth. Middlesex: Penguin Books. 1964.

HEBB. D.O. The organization of behavior. New York: Wiley, 1949.

HUNT, D. Parents and children in history. New York: Basic Books, 1970.

HUNT, J. Mc V. Intelligence and experience. New York: Ronald Press, 1961.

KAMII. C.K. An application of Piage(s theory to the conceptualization of a preschool

curriculum. In R.K. Parker (Ed.). The preschool in action. Boston: Allyn & Bacon,

1972.

KELLAGHAN, T. The evaluation of an intervention programme for disadvantaged

children. Slough. Berks: NFER Publishing CD .. 1977.

KOHLBERG, L. Early education: A cognitive developmental view. Child

Development. 1968. 39. 1013-1062.

LAVATTELLI, C.S. Piaget's theory applied to an early childhood curriculum.

Boston: American Science and Engineering. 1970.

LAVATTELLI, C.S. (Ed.) Language training in early childhood education. Urbana,

III.: University of Illinois Press, 1972.

LAWRENCE, E. lEd.). Friedrich Froebel and English education. Landon.' Routledge

& Kegan Paul. 1952.

LAZERXON. M. The historical antecedents of early childhood education. In I. J.

Gordon (Ed.). Early childhood education. The Seventy-first Yearbook of the National

Society for Study of Education. Part II. Chicago: NSSE. 1972.

LUSCHER, K. Building ecologies for human development: Towards a social policy for

the Child In Centre for Educational Research and Innovation. Children and society.

Issues for pre-school reforms. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

Development. 1981.

MADAUS. G.F .• AIRASIAN. P.W .. & KELLAGHAN. T. School effectiveness: A

reassessment of the evidence. New York: McGraw· Hill, 1980.

20

McKENNA. A. Psychology and preschool education. Irish Journal of Psychology.

1979.4. 131-140.

o CONCHOBHAIR. S. Are we serving the system instead of the scholar? Irish

Broadcasting Review, Spring 1979, 4. 7.-12.

PETERS. D.l. Social science and social policy and the care of young children: Head

start and after. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 1980. 1, 7.27.

PSACHAROPOUlOS. G. The economics of early childhood services. Paris:

CERIIOECD. 1980.

ROBINSON. N.M .. ROBINSON. H.B .. OARLING. M.A .• & HOLM. G. A world of

children. Daycare and preschool institutions. Monterey, California: Brooks/Cole

Publishing Co.. 1979.

ROBISON, H.F .• & SPODEK. B. New directions in the kindergarten. New York:

Teachers College Press, 1965.

SEARS, P.S .• & DOWlEY. E.M. Research on teaching in the nursery school. In N.L.

Gage (Ed), Handbook of research on teaching. Chicago: Rand McNally, 1963.

SIGEL, I.E. Developmental theory and pre,school education: Issues. problems and

implications. In I.J. Gordon (Ed). Early childhood education. The Seventy-first

Yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education. Part II. Chicago: NSSE.

1972.

STODOlSKY. S. Defining treatment and outcome in early childhood education. In H.

J. Walberg & A. T. Kopan (Eds.). Rethinking urban education. San Francisco:

Jossey-Bass. 1972.

TAMBURRINI. J. New directions in nursery school education. In c. Richards (Ed),

New directions in primary education. Lewes. Sussex: Falmer Press. 1982.

TAYLOR. P.H .. EXON. G .. & HOLLEY. B. A study of nursery education. London:

Evans/Methuen, 1972.

VAN DER EYKEN, W. The education of three-to-eight year olds in Europe in the

eighties. Windsor, Berks: NFER-Nelson Publishing Co. 1982.

WEBER, l. The English infant school and informal education. Englewood Cliffs.

New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. 1971.

WEI KART. O.P .. ROGERS. L. ADCOCK. C .. & McCLELLAND. D. Thecognitively

oriented curriculum. Washington. D.C.: ERIC/National Association for the

Education of Young Children. 1971.

WOODHEAD. M. Preschool education in Western Europe: Issues. policies and

trends. London: Longman. 1979.

21

Education and the psychological and

physical development of young

children

Anne T. McKenna

Lecturer, Department of Psychology,

University College Dublin

In talking to an audience of teachers in Mary Immaculate College

for Teachers I am conscious that my audience is both well informed

and highly experienced in the topic under discussion - Education and

the Psychological and Physical Development of Young Children. I am

sure you all remember singing as children a song that went:

"Who shaves the barber, the barber, the barber,

Who shaves the barber, the barber shaves himself".

This morning I have been given the task of shaving the barber. But

as the organisers of this excellently conceived seminar know, it has to

be done, and in holiday time even the best of barbers don't mind

letting somebody else do it for them.

Growth and Development

If we think of the child's growth and development as beginning at

conception and finishing somewhere around twenty years of age, it is

obvious that the increase in growth is not uniform throughout this

period. We all know that in the first year of life growth is rapid in

comparison to the rest of the life span; that it slows down until the

years between nine and twelve years, when there is another burst of

growth before the adolescent reaches adult height. All systems and

parts of the body, however, do not grow at the same rate.

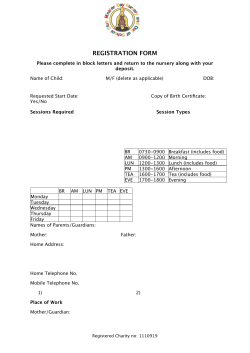

It can be seen from Figure I that by four years of age, the child's

brain and head have reached 80 per cent of their ultimate growth,

whereas their general growth status for the rest of the body has

reached only 40 per cent of that at twenty years. In other words the

brain and head are precociously developed, relative to the rest of the

bodily systems. What does this mean for the development of function

in the child, for the development of the child's competencies in motor

development and motor control, and for cognitive development?

The question of brain growth is highly relevant to our topic of

psychological development and education, since we know that the

23

100

/'",; - Brain :nd head

80

"llc

·s

~

~

/

/

/

60

I

I

I

40

I

Q

l

.~

VI

General

20

Reproductive

-'-'-'-'-'0

8

2

4

6

/

!

!

i

I

!

.I

./

8 10 12 14 16 18 20

Agt (years)

Fig. 1. Typical growth curves of three different parts or tissue of the body from

birth to age 20 (Adapted from Mussen (Ed) Carmichael's Manual of Child

Psychology 1970. p. 85)

brain is where messages from the outside world finish up, where they

are linked and coordinated, where the long-term memory traces are

laid down, where logical thinking is situated and where language is

located. How do all of these things relate to brain growth and

ultimately to age; are they parallel to brain growth; do they emerge

immediately after the growth takes place or years after; are they

affected by the amount and kind of stimulation the child receives in

these early years? These are questions to whlch neuro-physiologists,

psychologists and teachers of young children seek answers, answers

. of which at the moment we can only catch tantalising hints and clues.

Language

Where we have the greatest and the most secure knowledge is in

the area of language development, and here the emerging functions

appear to follow very closely the developing structures in the brain.

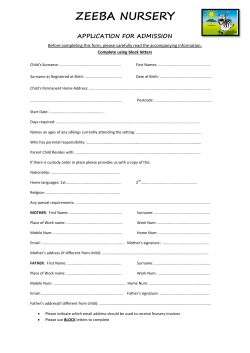

Figure 2 shows the growth of vocabulary items in young children.

It can be seen that this growth parallels the growth in brain and

head size, with the greatest increase occurring between two and a

half and three years, and the rate of increase slowing down

thereafter. The number of words a child has in her vocabulary is a

good indication of overall language development, although they are

not the most characteristic aspect of child language: they are merely,

as it were, the tip of the iceberg. As you know, we expect an infant of

one year to have two orthree words in their vocabulary, but by the age

of two years we expect the toddler to be ablp. to put two words together

in a relationship. Between one year and ,VIIO years of age, the child

has, as one psychologist put it, "stepped into the human race". This is

in fact precisely and biologically accurate. Between two years and

four to five years, the child in normal circumstances has acquired the

necessary and intricate skills of learning to speak - using three, four

or five word sentences, changing the end of words for number and

tense, joining two sentences together, embedding one within

24

another. The child can be accurately called a linguistic genius

between the years of two and four, the genius beginning to fade a

little at five to six years, and at eight almost all traces of originality

have gone. That is not to say that the child will not use ideas and have

original thoughts, but she will not be able to invent new wordseffortlessly and spontaneously, nor acquire a complex linguistic

system with such ease.

5000

2fiOO

:'i 1000

~

.".cE

500

m

250

""

100

-•

.<

.9

,>0

"~

0

>

."-,

~

£

-

50

25

0

t

E

10

z

5

"

0

-

2.5

0.1

1

2

3

4

5

6

Yean or age

Fig. 2. Logarithmic growth curve of the acquisition of recognition vocabulary by

children from infancy to six years of age. (After Smith. 1926.)

Recently a three year old advised me "We'd better dothat, bettern't

we?", and I reckoned, as I'm sure you will too, that such a creation was

beyond my capability, althourJh we can all und"erstand'what was

meant. I would be incapable of making up such an example to

illustrate this point. But this should not be too surprising if we think of

it. Our ancestors, creatures like ourselves, made up a language "out

of their own head", as children so graphically put it, and young

children repeat this creative ability for a short time. The only

surprising thing is that we as adults do not respect it more, but seem

to keep most of our attention for related inessential aspects of

emerging speech like proper pronunciation, or remembering to say

"Please" and "Thank" you". Relative to what the child has learned

and is learning, these are minor skills: to ask a child to repeat her

25

utterance, but remembering to say it properly this time, is a little like

rebuking a man who has just saved you from drowning for not waiting

to be properly introduced first. There is much that the adult can do to

enrich the child's language, but it does not include correction of

gratuitous speech. Indeed such corrections often have the opposite

effect to that desired, viz. inhibiting the child's precious flow of

speech.

What then is the parent's or teacher's role in fostering language

development in the years from three to five? Some years ago in

speaking to an audience of early educators on the subject of child

language, I was at great pains to explain the importance of language

in the school curriculum in the period just after language has been

acquired, i.e. from four to six years. I entitled the lecture "Child

Language: old shoe or magic slipper", to express the idea that most

children will slip into language easily and comfortably as into an old

shoe, because they belong to a species that is made to speak a

language: they are as it were, pre-programmed to speak. True, they

need to be exposed to Irish or English or Chinese to be able to speak

Irish or English or Chinese, but they do not need someone standing

over them to see that they learn it. In these linguistic years, they

appear to pick out what they need in a remarkably quick time, and this

short exposure sets off their own language into an empty head, but

more like exposing the child to a little language which will then act as

a trigger to set off the child's own biologically pre-existing language

"programmes". Just as we cannot say that a child "learns" to walk,

because walking comes with growth and without much help from

anyone, so it is to some extent with language. Just as we might say

she "took her first steps" at fourteen months, so too should we say

she "put her first two words together" at twenty months. We are

wired up, prepared to speak, and this happens between the ages of

two and four years.

This early biological thrust to speaking and listening, or to what are

sometimes called the primary linguistic processes, does not apply to

reading and writing, the secondary linguistic processes. We are not

wired up to read and write, no more than we are to broadcast on radio

or to make audio-visual cassettes. Reading and writing, like these, are

man-made artificats. There is nothing inevitable about them, and

some cultures do not even have a written language, no more than

they have libraries or TV sets. Whereas we might say then, that the

years from two to four are biologically controlled, the years from four

to six may be said to be environmentally or socially controlled, or if the

child is at school, educationally controlled. And it is at this point.

beginning around three or four years of age, that the old shoe mayor

may not become a magic slipper, a magic slipper to carry the child into

the realms of literacy and human culture by means of books and

reading.

The language that the great bulk of four year olds possess on

entering school is perfectly adequate to carry them through all the

26

normal home and play transactions. They are able to express their

wants to their parents, be it for a drink, for sweets or to be taken to

MacDona Ids. They can shout and protest if someone annoys them, or

tell tales on another child, and report when they are feeling sick. They

can ask where their bike or lost shoe is, and pester their parents for

special treats. But all this is of a quite different quality to written

language. I do not propose here to discuss all the differences between

written and spoken language. The main difference is that most of our

spoken language and almost all of a four year old's language is

context-bound, whilst written language is not. One has to be in the

presence ofthe child to get her message, whereas a book may be read,

and usually is, in total isolation. For example, if you asked a five year

old a question like: "Who told you to draw on the paper?", the answer

would likely be "Her" or "She did", pointing at or just looking at the

person concerned. Most of the message comes from the meaning of

the gesture and the total situation, with the words carrying relatively

little information. And why should it be otherwise? If that message

were to stand on its own without gestures, as in a written passage it

would have to be something like: "The woman with the white blouse"

or "The woman that's minding me". Why should you say allthatwhen

you can do it so much more economically with a gesture, throwing in

perhaps one word for good measure. The gesture plus pared down

speech can make for effective inter-personal communication but it is

of little use in such non-personal communication as reading and

writing. The structure of reading and writing is more elaborate

because it has to carryall the information. As well as being selfsufficient it also has to be "rounded off", as half finished sentences

are not tolerated in writing as they are in speaking. The difference

between the language that the four year old brings to school, and the

language of reading books or written language, is the difference we

feel our selves between talking to someone and writing a letter to

them conveying the same information. The reason that the latter

gives us so much trouble does not reside in the motor act of writing so.

much as in the fact that we have to do a translation job first: we have

to translate our speech into written language, then write this written

language on paper.

The language of books, even of infant readers, is of necessity a

written language and therefore unknown to the non-reading child.

Perhaps it would be more accurate to say unknown to some children

because it is here that we find one of the most important sources of

individual diffElrences, differences which are due almost entirely to

the home Jckground and socio-economic status of the family. The

child who has a repertoire of songs and poems, who has had stories

read to her, who has been encouraged to use speech for comment and

discussion as well as for on-going transactions, is already initiated

into written or "school" language. For the others, the teacher may be

the Open Sesame. The teaching task is to build a bridge between the

child's very impressive and effortlessly acquired speech, and his

27

ability to read written language, and to put his own speech in writing.

The child will acquire this only with considerable difficulty, and with

great effort on his part and on the part of his teacher.

These findings -from recent experimental research in the

psychology and sociology of language have far-reaching

consequences for practice in the infant classes. There are a numberof

ways in which the teacher might build them into classroom practice,

depending on the time available for individualised instruction.

1.

The child's own speech can be transformed into reading

material. This is not the same thing as constructing an

"experience" reader from the child's own background of

experience. It is doing this but doing it in the child's own words;

we might call them linguistic experience readers. There is only

one way to do this accurately and that is to make a recording of

the child's speech. If this permanent record is not present for

evidence, the adult will gloss the child's speech and not even be

aware of the fact that they have tidied it up. Such a written

record would look something like this: "My Mammy is nice and

she's called Mary. My Mammy a/ways makes my tea, so she

does". The more usual written version found in books, even

children's books, would not repeat Mammy the second time but

say "she" instead, and would not contain the little bit of

circularity at the end which we all use in some shape or form

when we talk, but not when we write. These are just a few of

the differences between the child's language and written

language. However, we cannot gauge how a child might

construct his sentence until we have it on record. We know only

that it is likely to be very different from reading book language.

2.

The child's existing speech can be improved upon and the child

can learn how to transform this into a closer approximation of

written language when the occasion demands. This is

sometimes called teaching for "language lift" or promoting

aracy. The term oracy is a useful one as it reminds us that we are

not teaching the child to speak: he can already do that. Our task

is (a) to get the child to put his language skills to work in the

classroom by whatever means we can, and (b) to work on this

freely expressed language to prepare for reading. Oracytraining

has received great attention in the last few years in many

countries. We might mention in passing the Bullock Report, subtitledA Language for Life, and the many practical programmes of

oracy, the best known being probably those of Joan Tough and

the Gahagans, all of the United Kingdom.

3.

A third aid in transforming or lifting child's language in the infant

class is both traditional and routine in the infant programme, viz.

the reading of stories to children. There is a structure or format

to all stories, more subtle and often more undetected than that of

a beginning and an end. The "once upon a time" at the

beginning and the "happy ever after" at the end are part of the

28

structure, but there are other equally predictable elements in

between. There is a central character, usually a little boy or girl,

with a family constellation and friends around her. When there

is a journey, there will be a setting-off followed by an arrival.

Children who are fortunate enough to come from homes where

stories are frequently read to them will have a variety of story

structures which will match all eventualities without

necessarily having one word of "reading". How often have you

witnessed such a non-reading child go through, for example, an

entire Ladybird book, getting the sequences in their correct order

and sometimes - and sometimes not - reciting the written

words in parrot fashion. Such a child is half-way to reading, and

is engaging in the best kind of pre-reading activity. Psychologists

studying children's cognitive processes have interested

themselves in the kind of story structures or "scripts" that

children can call on from inside their memory. It is obvious that

the greater amount of scripts that the child has, the more

predictable will be the written material of the stories and the

better able will he be to guess what.comes next. We have known

for a long time that reading or telling stories to children helps

their speech and reading, and now we know that it is because

the repeated story structures are forming a scaffolding for future

forward planning when the child faces a page of text.

The other pre-reading skills such as letter discrimination, matching

letters to sound and word building, are well recognised and catered

for in the infant programme, butthe basic one of matching spoken and

written language, or the teaching of oral skills is now seen to be the

most effective because it is the most basic skill for embarking on

reading.

Returning then to the question of brain growth and language

development, it follows that if the basic syntactical and

communicative abilities are laid down by four years of age, then atthis

juncture, and perhaps even earlier, all children will benefit from

language enrichment and teaching of oral skills. Every month that

passes is taking the child from those twenty or so months of optimal

language acquisition in the linguistic genius period of development:

every month that passes is wideni ng the gap between the

competencies of the child from the language-stimulating home

background and those of the child from the language-deprived home

background, a gap that good infant teaching can hope to narrow.

Cognitive Skills

Closely tied up with the child's developing language skills is the

growth of conceptual development. Concepts may be called the tools

of thought and it is indeed with these that children build up their store

of knowledge and skills t~rough primary school and thereafter. The

primary teacher may take many of the basic concepts for granted: the

infant teachF!f dare not. When the child enters school, he has an array

29

of practical concepts which, again, like language, he has picked up for

the business of living, sleeping, eating, shopping and playing. The

world of concepts to which he will now be initiated in school, are

those which divide up our world mathematically and scientifically,

concepts of colour, time, space, size, number, and logic. There is,

accompanying the learning of these concepts, a vocabulary, a

technical language so to speak, which the child must know.

The difficulty in introducing these first, all-important concepts to a

four and five year old is that the language accompanying them is

deceptively easy. If it were a technically abstruse vocabulary like that

of chemistry or astronomy, we might do it better. The words for the

concepts we are teaching are every-day words like more, less, bigger,

in front of. later and soon. Because they are parts of our every-day

speech, we are tempted to take them for granted, not fully

appreciating the abstract structures they represent. Table 3 shows

some of the basic scientific and social concepts that must be learned

by a child. Those on the left hand side are abstract words showing the

areas we are trying to teach: the words on the right hand side are the

examples of these concepts we need toteach the child, and I think it is

obvious from the table that they are in fact words in every-day use.

Table 3. Typical Examples of Early Concepts

SPACE

nearlfar

on top of

TIME

morning/night

Saturday June

SIZE

bigger Ismallest

NUMBER

"none left"

a pair of

LOGIC

same as/different

if

SOCIAL

happy/sad

myself daughter

The familiarity of the words should not blunt an awareness ot their

inherent difficulty. If we do not recognise this, w~ ~annot plan fortheir

acquisition, and tick them off systematically when that has been done

for each single child in our care. Such detailed ticking-off requires a

level of detail in excess of that in the current Department of Education

Curriculum. However, the great upsurge in interest in early childhood

education over the last two decades has resulted in a plethora of

excellent curricula and handbooks. These tend to converge on well