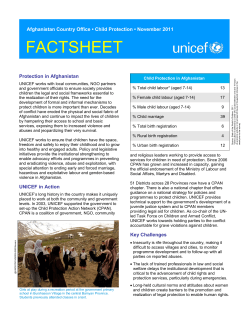

Document 72393