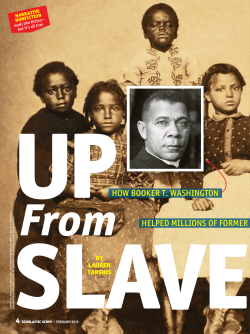

Up from Slavery TG