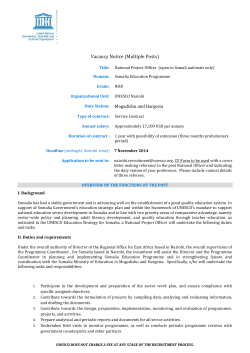

The right to education