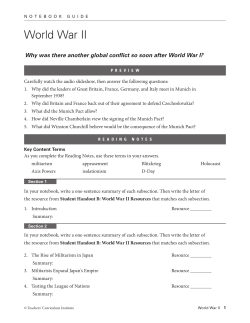

Holocaust Learning Trunk Project