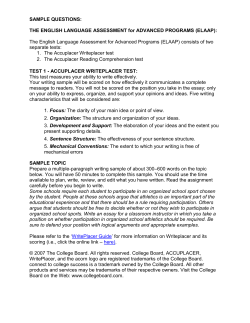

Gruber`s