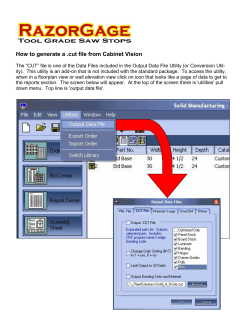

Leadership for the long term: Whitehall`s capacity to address future