Zeng 1..6 - Science Advances

RESEARCH ARTICLE NANOMATERIALS Structural patterns at all scales in a nonmetallic chiral Au133(SR)52 nanoparticle 2015 © The Authors, some rights reserved; exclusive licensee American Association for the Advancement of Science. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial License 4.0 (CC BY-NC). 10.1126/sciadv.1500045 Chenjie Zeng,1 Yuxiang Chen,1 Kristin Kirschbaum,2 Kannatassen Appavoo,3 Matthew Y. Sfeir,3 Rongchao Jin1* Structural ordering is widely present in molecules and materials. However, the organization of molecules on the curved surface of nanoparticles is still the least understood owing to the major limitations of the current surface characterization tools. By the merits of x-ray crystallography, we reveal the structural ordering at all scales in a super robust 133–gold atom nanoparticle protected by 52 thiolate ligands, which is manifested in self-assembled hierarchical patterns starting from the metal core to the interfacial –S–Au–S– ladder-like helical “stripes” and further to the “swirls” of carbon tails. These complex surface patterns have not been observed in the smaller nanoparticles. We further demonstrate that the Au133(SR)52 nanoparticle exhibits nonmetallic features in optical and electron dynamics measurements. Our work uncovers the elegant self-organization strategies in assembling a highly robust nanoparticle and provides a conceptual advance in scientific understanding of pattern structures. INTRODUCTION The atomic structure of nanoparticles is of paramount importance because many applications (such as catalysis and biomedicine) and fundamental studies of quantum size effect in ultrasmall nanoparticles require structural details at the atomic level (1–3). Thus, significant research efforts have been put forth to uncover the structure of nanoparticles (4–7). Among the different types of nanoparticles, gold nanoparticles protected by thiolate ligands (–SR) serve as a paradigm system and constitute an important platform for nanotechnology. Novel nanomaterials with different functionalities are created through manipulating the surface structure of gold nanoparticles (8–11). In recent years, great advances have been made in controlling the quality of thiolate-protected gold nanoparticles (5, 6, 12, 13), and the syntheses of such nanoparticles have reached atomic precision, with a series of reported magic sizes ranging from tens to hundreds of gold atoms (7, 14–16). Such advances have led to total structure determination of a few magic-sized nanoparticles by x-ray crystallography (3, 6, 17–19). The crystal structures provide valuable information on the structural construction and evolution rules in the gold nanoparticles with dozens of gold atoms, and also shed light on the structure of the gold-thiolate interface, which had been sought for decades (20). However, since the first report of the Au102(p-MBA)44 structure (where p-MBA = SPh-p-COOH) (6), it still remains a daunting task to elucidate even larger structures of gold nanoparticles—which are critically important to understand the growth pattern, surface structural ordering, and the emergence of metallic properties. Here, we report the hitherto largest crystallographic structure of a chiral gold nanoparticle having 133 gold atoms and 52 surface-protecting thiolate ligands. The Au133(SR)52 nanoparticle (where R = SPh-p-But and the same hereafter) exhibits aesthetic orderings from the gold kernel to the Au-S interface to the carbon tails of thiolates, with a kaleidoscope of patterns at the atomic, molecular, and ensemble scales: (i) the gold kernel follows a shell-by-shell growth pattern, forming a 1 Department of Chemistry, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA. College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, University of Toledo, Toledo, OH 43606, USA. 3Center for Functional Nanomaterials, Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, NY 11973, USA. *Corresponding author. E-mail: rongchao@andrew.cmu.edu 2 Zeng et al. Sci. Adv. 2015;1:e1500045 20 March 2015 quasi-spherical Au107 kernel comprising a Au55 two-shelled icosahedron and a third Au52 transition shell; (ii) the gold-thiolate interface exhibits a helical “stripe” pattern in which the S–Au–S motifs stack into ladders in the curved space; (iii) the carbon tails of thiolates further form “swirl” patterns that are different from the underlying S– Au–S stripe patterns; (iv) the ensemble packing of nanoparticles gives rise to a triclinic single crystal. The icosahedron-based gold kernel illustrates shell-by-shell growth at the atomic scale and constitutes a smaller counterpart of the 20-fold twinned icosahedral gold nanoparticle observed under an electron microscope (21). The resolved –S–Au–S– helical stripes provide the first crystallographic proof for the formation of selfassembled monolayer (SAM) structures on the curved surface of nanoparticles (10) and offer clues to the SAMs on flat surfaces (22). The –S–Au–S– helical stripes, together with carbon-tail swirls on the spherical gold kernel, also illustrate the unique patterning in the curved space, reminiscent of the twist of ropes, capsids of viruses, and the “hairy ball theorem” (10, 23–25). These self-assembled hierarchical patterns in the chiral Au133(SR)52 nanoparticle have not been observed in the previously reported gold nanoparticle structures, which were not large enough to support the extended patterning structures. The observed structural features in Au133(SR)52 demonstrate nature’s patterning strategies in fabricating large and robust nanostructures. The Au133(SR)52 nanoparticle can be viewed as a transitional state in geometric structure from small nanoclusters toward large nanoparticles. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION The magic-sized Au133(SR)52 nanoparticle was obtained via a thermal reaction of molecularly pure Au144(SCH2CH2Ph)60 nanoparticles (26) with excess 4-tert-butylbenzenethiol at 80°C for 4 days (see Supplementary Materials for details). The Au133(SR)52 nanoparticles crystallized in space group P1; the final anisotropic (Au and S atoms) refinement converged at R1 = 8.65% for the observed data (tables S2 to S4). Figure 1 shows the total structure of an enantiomer of the Au133(SR)52 nanoparticle and packing of the racemic pair in the crystal. The diameter 1 of 6 RESEARCH ARTICLE (expected m/z = 11,729.77, deviation: 0.13); that is, the nanoparticle’s intrinsic charge is zero. The 133 gold atoms in the nanoparticle are distributed in four shells, that is, one central atom with successive shells of 12, 42, 52, and 26 gold atoms (Fig. 2, A to D). The central atom and the first shell form a 13atom icosahedron (Fig. 2A), which is enclosed by a second 42-atom icosahedral shell (Fig. 2B, gray), forming the 55-atom Mackay icosahedron (Au55-MI) (27). The Au55-MI can be viewed as 20 tetrahedral units joined together with a common vertex (that is, the center) through sharing three adjacent facets. The gold atoms in each tetrahedral unit are assembled in a layered a-b-c manner (Fig. 2, E and F, green-pink-gray), that is, cubic closepacking. This is indeed the first observation of the icosahedral Au55 motif, which has long been sought since Schmid et al. reported phosphine-protected Au55 nanoparticles in 1981 (28). The third shell serves as a transition layer between the Au55-MI and the surface layer and is largely dictated by the surface. This shell is constructed through capping the 20 exposed triangular (111) facets of Au55-MI (Fig. 2C), with 16 facets each capped by three gold atoms in an a-bc-b manner (Fig. 2E, capping atoms highlighted in cyan) B and the remaining four facets each capped by only one gold atom in an a-b-c-a manner (Fig. 2F, capping atom in blue), hence totaling 52 gold atoms in this third shell. The 52 gold atoms actually provide the “footholds” for the 52 thiolate ligands. Overall, the 107 gold atoms in the first three shells constitute a nearly perfect sphere with a diameter of 14 Å (atomic-center-to-center distance). The Au-Au bond lengths between successive shells (that is, radial bonds) and within each shell (that is, transverse bonds) are listed in table S1. The radial bonds (r) are shorter than the transverse bonds (a); for example, the average bond length between the central gold atom and the first shell is r = 2.760 ± 0.008 Å, whereas the bond length within the first icosahedral shell is a = 2.920 ± 0.035 Å. Their ratio (that is, 2.760/ 2.920 = 0.945) closely matches the geometry requirement (r = 0.95a) of an icosahedron. The fourth gold shell contains 26 gold atoms, which combine with 52 thiolate ligands to form the surface of the Au133(SR)52 nanoparticle (Fig. 2D). The surface gold atoms and thiolates are organized into 26 –S–Au–S– staFig. 1. Total structure of chiral Au133(SR)52 nanoparticle characterized by x-ray ple motifs. The 52 thiolates terminate the 52 gold atoms crystallography. (A) An enantiomer of the chiral Au133(SR)52 nanoparticle. Magenta: of the third shell in a one-on-one manner (Fig. 2G), that gold; yellow: sulfur; gray: carbon; white: hydrogen. (B) Ensemble packing of Au133(SR)52 is, 26 (staples) × 2 (footholds per staple) = 52 sites. The nanoparticles in P1 space group. The left- and right-handed enantiomers are indicated in surface-protecting monomeric staples require that the magenta and green. underlying foothold Au-Au distance (4.872 ± 0.377 Å) of the entire nanoparticle (including the ligand shell) is ~3.0 nm, roughly matches with the span of the staple, that is, twice the Au(staple)-S with the metal core diameter being ~1.7 nm. The Au133(SR)52 nano- bond length (2 × 2.319 ± 0.023 Å). Together, the Au133(SR)52 nanoparticle is charge-neutral, evidenced by electrospray ionization mass particle can be divided into [Au1-Au12-Au42-Au52][Au(SR)2]26. spectrometry analysis; thus, cesium acetate was added to form posiThe monomeric staples (–S–Au–S–) are self-assembled into aestively charged cesium adducts of the Au133(SR)52 nanoparticle (15). thetic “helical stripes” on the spherical surface of the Au107 kernel Two strong peaks at mass/charge ratio (m/z) = 17,528.3 and (Fig. 3). Each stripe comprises six staples that are parallel to each 11,729.9 are observed (fig. S1), corresponding to [Au133(SR)52 + 2Cs]2+ other and form a ladder-like helix with a width of ~4.9 Å (Fig. 3, A (expected m/z = 17,528.20, deviation: 0.1) and [Au133(SR)52 + 3Cs]3+ and C). The four helices emanate from one pole of the globular A Zeng et al. Sci. Adv. 2015;1:e1500045 20 March 2015 2 of 6 RESEARCH ARTICLE Fig. 2. The four-shell structure of Au133(SR)52. (A to D) The first icosahedral shell with 12 Au atoms (pink) (A); second icosahedral shell with 42 Au atoms (gray) (B); third shell with 52 Au atoms (blue and cyan) (C); fourth shell with 26 Au atoms (orange) and 52 sulfur atoms (yellow) (D). (E) Layered a-b-c-b packing of Au atoms in a tetrahedral unit of an icosahedron; total of 16 such units. (F) a-b-c-a packing of atoms; total of four such units. (G) Monomeric –SR–Au–SR– motifs clamping on the third shell gold atoms. Carbon groups are omitted for clarity. Au107 kernel and coil up like a four-stranded rope (24) and converge at the other pole (Fig. 3, B and C). The clockwise and anticlockwise rotations of the four helices give rise to chirality in the Au133(SR)52 nanoparticle (that is, the left- and right-handed isomer pair in the unit cell; Figs. 1B and 3D). Such a self-organized helical –S–Au–S– stripe pattern on the surface of a nanoparticle is remarkable. It provides the first crystallographic evidence that highly ordered patterns of staple motifs can form on the extended curved surface of nanoparticles. This is in contrast to the smaller Au102(pMBA)44 structure (6), in which the –S–Au–S– motifs do not form such an ensemble pattern. It is worth noting that rectangular stripes (rather than helical stripes) were previously observed on flat gold film by scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) (22). Also, Jackson et al. reported ripple-like stripe domains on mixed-thiolate monolayer–protected gold nanoparticles through STM analysis (10, 29). The crystallographically characterized helical stripe patterns of –S–Au–S– motifs provide more insight into those systems. Resolving every thiolate ligand by x-ray crystallography allows us to further examine the arrangement of the Ph-p-But carbon tails on the spherical surface. Surprisingly, the carbon tails do not adopt the same helical stripe pattern as that of the underlying –S–Au–S– motifs; that is, the orientation of carbon tails do not follow the allcis or all-trans conformation in each –S–Au–S– stripe. Instead, the tails tend to self-organize into multiple swirls in accord with the spherical surface of the nanoparticle (Fig. 4A), and each swirl consists of four rotatively arranged phenyl rings (Fig. 4B). Such a twisted arrangement of phenyl rings in Au133(SR)52 is in contrast with the preferred parallel stacking of phenyl rings of p-MBA (that is, SPhp-COOH) ligands in Au102(p-MBA)44 (6). The swirly arrangement of phenyl rings can be attributed to the combined effects of spherical surface and bulky tert-butyl substituents and is a more compact packing mode compared to the parallel stacking of phenyl rings. It Zeng et al. Sci. Adv. 2015;1:e1500045 20 March 2015 is worth noting that self-assembly of carbon tails of the ligands on the Au133 surface also induces chirality (Fig. 4A), but the chiral pattern is different from that formed by the –S–Au–S– motifs (that is, swirls versus helices). The surface patterns of both the helical ladders of –S–Au–S– motifs and the swirly distribution of carbon tails destroy the perfect symmetry of the spherical gold kernel and may act as specific reaction sites for functionalization (10, 30). The extraordinary stability of the Au133(SR)52 nanoparticle is largely attributed to its highly ordered geometric structure. The hierarchical patterning from the inner gold core to the surface ligand shell minimizes the internal stress of the nanoparticle. Furthermore, the proper arrangement of the staple motifs and carbon tails provides full protection of the Au133 nanoparticle’s surface from attack by excess thiols or other chemicals. In terms of the electronic factor, the Au133(SR)52 nanoparticle has 81 valance electrons (that is, 133 − 52 = 81), which is an odd number and does not match with the superatom series (for example, 2, 8, 18, 58, 92…). As the size of nanoparticles increases and the spacing between the electronic orbitals decreases, the geometric effect will contribute more to the stability of nanoparticles than the electronic effect (7). To probe whether the Au133(SR)52 nanoparticle is in the metallic state, we performed ultraviolet-visible (UV-vis) absorption and femtosecond transient optical measurements. The Au133(SR)52 nanoparticles exhibit a highly structured UV-vis spectrum with absorption bands at 336, 421, 503, and 712 nm (Fig. 5A), being distinctly different from the single plasmon band (for example, at ~520 nm) of metallic-state spherical nanoparticles. Thus, Au133(SR)52 nanoparticles are nonmetallic in nature, which is further supported by femtosecond broadband transient absorption measurements. Upon photoexcitation above the optical gap, we observe three primary transient optical features (Fig. 5B), including a net bleach near 500 nm and two net positive features of excited-state absorption at ~580 and 3 of 6 RESEARCH ARTICLE 640 nm (Fig. 5B, lower panel). The bleach at 500 nm correlates to the ground-state transition at 503 nm observed in Fig. 5A. The other ground-state transition observed at 712 nm is superimposed on the excited-state absorption features such that no net negative signal can be seen. These overlapping contributions cannot be rigorously separated (for example, using global analysis) because identical kinetics are observed at all wavelengths in our data set. This is illustrated in the right panel of Fig. 5B, where decay kinetics at each Fig. 3. Self-assembled –S–Au–S– helical stripes on the spherical Au107 kernel. (A and B) Side views. (C and D) Top views. The two chiral isomers are shown in (D). Each stripe is composed of six monomeric staples stacked into a ladder-like helical structure. Yellow: sulfur; orange/red/blue/green: gold in the helices; purple: gold in the independent monomeric staples. Fig. 4. Chiral self-assembly of the carbon tails of the SPh-p-But ligands. (A) The rotative arrangement of phenyl rings results in the formation of fourfold swirls. (B) Carbon-tail swirls on the square unit; top: left-handed isomer; bottom: right-handed isomer. Yellow: sulfur. Zeng et al. Sci. Adv. 2015;1:e1500045 20 March 2015 4 of 6 RESEARCH ARTICLE Fig. 5. Optical properties of Au133(SR)52 nanoparticles. (A) The dashed lines represent peak positions extracted from fitting to a series of inhomogeneously broadened transitions and a nonresonant scatter background. (B) Image plot of transient absorption data with optical pumping at 420 nm, along with representative kinetics (absolute value) at wavelengths corresponding to the dashed lines in the image plot (right panel) and transient spectra (bottom panel) at 1 ps. (C and D) Normalized decay kinetics as a function of laser fluence with 500-nm pump pulses (C) and extracted values of the rate constant for the faster decay component of a two-exponential fit showing the fluence independence of the carrier dynamics (D). of the three primary transient features can be globally fit with just two time constants (~2.8 and ~30 ps). The absence of more complex spectral dynamics suggests that a single electronic configuration is responsible for all of the resolvable transient features. This is in contrast with the expected dynamics for a metallic-state nanoparticle (31, 32). All of the observed relaxation dynamics are independent of laser fluence, in sharp contrast to metallic noble metal nanoparticles (33). Normalized kinetic traces measured at either the bleach (500 nm) or the excited-state absorption features (580 nm, Fig. 5C) can be superimposed over an absorbed fluence range of 12 to 192 mJ/cm2. Both the faster (~2.8 ps) and slower components (~30 ps) of the biexponential decay are found to be independent of pump fluence and pump wavelength (Fig. 5D). These results significantly differ from the traditional carrier relaxation processes in metallic-state nanoparticles, where carrier cooling is described by the two-temperature model (31, 33). Within this model, the rate of thermal equilibration between the electronic and lattice subsystems is described by a conZeng et al. Sci. Adv. 2015;1:e1500045 20 March 2015 stant electron-phonon coupling term, such that an increase of the electronic temperature (at high laser fluence) results in a longer relaxation time. Together, our results suggest that despite its relatively large size, the unique structure of the Au133(SR)52 nanoparticle delays the onset of metallic behavior. SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/ full/1/2/e1500045/DC1 Materials and Methods Fig. S1. Electrospray ionization mass spectrum of Au133(SR)52 nanoparticles. Table S1. Au-Au bond lengths in the Au107 kernel. Table S2. Sample and crystal data for Au133. Table S3. Data collection and structure refinement for Au133. Table S4. Atomic coordinates and equivalent isotropic atomic displacement parameters (Å2) for Au133. 5 of 6 RESEARCH ARTICLE REFERENCES AND NOTES 1. M. Behrens, F. Studt, I. Kasatkin, S. Kühl, M. Hävecker, F. Abild-Pedersen, S. Zander, F. Girgsdies, P. Kurr, B. L. Kniep, M. Tovar, R. W. Fischer, J. K. Nørskov, R. Schlögl, The active site of methanol synthesis over Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 industrial catalysts. Science 336, 893–897 (2012). 2. N. L. Rosi, D. A. Giljohann, C. S. Thaxton, A. K. Lytton-Jean, M. S. Han, C. A. Mirkin, Oligonucleotide-modified gold nanoparticles for intracellular gene regulation. Science 312, 1027–1030 (2006). 3. M. Zhu, C. M. Aikens, F. J. Hollander, G. C. Schatz, R. Jin, Correlating the crystal structure of a thiol-protected Au25 cluster and optical properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 5883–5885 (2008). 4. S. Billinge, I. Levin, The problem with determining atomic structure at the nanoscale. Science 316, 561–565 (2007). 5. H. Qian, M. Zhu, Z. Wu, R. Jin, Quantum sized gold nanoclusters with atomic precision. Acc. Chem. Res. 45, 1470–1479 (2012). 6. P. D. Jadzinsky, G. Calero, C. J. Ackerson, D. A. Bushnell, R. D. Kornberg, Structure of a thiol monolayer-protected gold nanoparticle at 1.1 A resolution. Science 318, 430–433 (2007). 7. H. Qian, Y. Zhu, R. Jin, Atomically precise gold nanocrystal molecules with surface plasmon resonance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 696–700 (2012). 8. C. A. Mirkin, R. L. Letsinger, R. C. Mucic, J. J. Storhoff, A DNA-based method for rationally assembling nanoparticles into macroscopic materials. Nature 382, 607–609 (1996). 9. W. A. Lopes, H. M. Jaeger, Hierarchical self-assembly of metal nanostructures on diblock copolymer scaffolds. Nature 414, 735–738 (2001). 10. G. A. Devries, M. Brunnbauer, Y. Hu, A. M. Jackson, B. Long, B. T. Neltner, O. Uzun, B. H. Wunsch, F. Stellacci, Divalent metal nanoparticles. Science 315, 358–361 (2007). 11. F. Manea, F. B. Houillon, L. Pasquato, P. Scrimin, Nanozymes: Gold-nanoparticle-based transphosphorylation catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 43, 6165–6169 (2004). 12. R. B. Wyrwas, M. M. Alvarez, J. T. Khoury, R. C. Price, T. G. Schaaff, R. L. Whetten, The colours of nanometric gold. Eur. Phys. J. D 43, 91–95 (2007). 13. N. K. Chaki, Y. Negishi, H. Tsunoyama, Y. Shichibu, T. Tsukuda, Ubiquitous 8 and 29 kDa gold:alkanethiolate cluster compounds: Mass-spectrometric determination of molecular formulas and structural implications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 8608–8610 (2008). 14. Y. Negishi, K. Nobusada, T. Tsukuda, Glutathione-protected gold clusters revisited: Bridging the gap between gold(I)-thiolate complexes and thiolate-protected gold nanocrystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 5261–5270 (2005). 15. C. Zeng, Y. Chen, G. Li, R. Jin, Magic size Au64(S-c-C6H11)32 nanocluster protected by cyclohexanethiolate. Chem. Mater. 26, 2635–2641 (2014). 16. Y. Song, J. Zhong, S. Yang, S. Wang, T. Cao, J. Zhang, P. Li, D. Hu, Y. Pei, M. Zhu, Crystal structure of Au25(SePh)18 nanoclusters and insights into their electronic, optical and catalytic properties. Nanoscale, 6, 13977–13985 (2013). 17. M. W. Heaven, A. Dass, P. S. White, K. M. Holt, R. W. Murray, Crystal structure of the gold nanoparticle [N(C8H17)4][Au25(SCH2CH2Ph)18]. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 3754–3755 (2008). 18. C. Zeng, C. Liu, Y. Chen, N. L. Rosi, R. Jin, Gold-thiolate ring as a protecting motif in the Au20(SR)16 nanocluster and implications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 11922–11925 (2014). 19. C. Zeng, H. Qian, T. Li, G. Li, N. L. Rosi, B. Yoon, R. N. Barnett, R. L. Whetten, U. Landman, R. Jin, Total structure and electronic properties of the gold nanocrystal Au36(SR)24. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 51, 13114–13118 (2012). 20. R. L. Whetten, R. C. Price, Chemistry. Nano-golden order. Science 318, 407–408 (2007). Zeng et al. Sci. Adv. 2015;1:e1500045 20 March 2015 21. M. R. Langille, J. Zhang, M. L. Personick, S. Y. Li, C. A. Mirkin, Stepwise evolution of spherical seeds into 20-fold twinned icosahedra. Science 337, 954–957 (2012). 22. O. Voznyy, J. J. Dubowski, J. T. Yates, P. Maksymovych, The role of gold adatoms and stereochemistry in self-assembly of methylthiolate on Au(111). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 12989–12993 (2009). 23. P. Ball, The Self-Made Tapestry: Pattern Formation in Nature (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2001). 24. I. R. Bruss, G. M. Grason, Non-Euclidean geometry of twisted filament bundle packing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 10781–10786 (2012). 25. J. M. Grimes, J. N. Burroughs, P. Gouet, J. M. Diprose, R. Malby, S. Ziéntara, P. P. Mertens, D. I. Stuart, The atomic structure of the bluetongue virus core. Nature 395, 470–478 (1998). 26. H. Qian, R. Jin, Controlling nanoparticles with atomic precision: The case of Au144(SCH2CH2Ph)60. Nano Lett. 9, 4083–4087 (2009). 27. A. Mackay, A dense non-crystallographic packing of equal spheres. Acta Cryst. 15, 916–918 (1962). 28. G. Schmid, R. Pfeil, R. Boese, F. Bandermann, S. Meyer, G. H. M. Calis, J. W. A. van der Velden, Au55[P(C6H5)3]12CI6—Ein Goldcluster ungewöhnlicher Größe. Chem. Ber. 114, 3634–3642 (1981). 29. A. M. Jackson, J. W. Myerson, F. Stellacci, Spontaneous assembly of subnanometre-ordered domains in the ligand shell of monolayer-protected nanoparticles. Nat. Mater. 3, 330–336 (2004). 30. C. L. Heinecke, T. W. Ni, S. Malola, V. Mäkinen, O. A. Wong, H. Häkkinen, C. J. Ackerson, Structural and theoretical basis for ligand exchange on thiolate monolayer protected gold nanoclusters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 13316–13322 (2012). 31. C. Yi, M. A. Tofanelli, C. J. Ackerson, K. L. Knappenberger, Optical properties and electronic energy relaxation of metallic Au144(SR)60 nanoclusters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 18222–18228 (2013). 32. S. Malola, L. Lehtovaara, J. Enkovaara, H. Häkkinen, Birth of the localized surface plasmon resonance in monolayer-protected gold nanoclusters. ACS Nano 7, 10263–10270 (2013). 33. J. H. Hodak, A. Henglein, G. V. Hartland, Electron-phonon coupling dynamics in very small (between 2 and 8 nm diameter) Au nanoparticles. J. Chem. Phys. 112, 5942 (2000). Acknowledgments: We thank T. Li for early trials on the crystal structure of Au133, Z. Zhou for assistance in electrospray ionization mass spectrometry analysis, and K. J. Lambright for assistance with the crystallographic experiment. Funding: This work was supported by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research under AFOSR award no. FA9550-11-1-9999 (FA9550-11-1-0147) and the Camille Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar Awards Program. Transient optical measurements were carried out at the Centre for Functional Nanomaterials, Brookhaven National Laboratory, which is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under contract no. DE-AC02-98CH10886. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests. Submitted 13 January 2015 Accepted 20 January 2015 Published 20 March 2015 10.1126/sciadv.1500045 Citation: C. Zeng, Y. Chen, K. Kirschbaum, K. Appavoo, M. Y. Sfeir, R. Jin, Structural patterns at all scales in a nonmetallic chiral Au133(SR)52 nanoparticle. Sci. Adv. 1, e1500045 (2015). 6 of 6

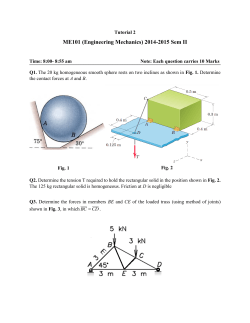

© Copyright 2025