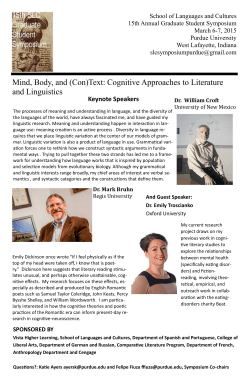

this new draft by Ramirez, Theofanopoulou and Boeckx

A hypothesis concerning the neurobiological basis of phrase structure building∗ Javier Ram´ırez1 , Constantina Theofanopoulou2 & Cedric Boeckx2,3 1 Universitat de Girona, 2 Universitat de Barcelona, 3 ICREA correspondence: cedric.boeckx@ub.edu March 2015 Abstract The goal of this paper is to offer a theoretical model of how the aspect of our linguistic cognition known as phrase-structure building may be implemented in neural terms. Our proposal concerning this brain implementation requires us to decompose phrase-structure building into more elementary sub-processes, which we suggest can be captured in terms of brain rhythms. The rhythms involved—alpha, beta, gamma, and theta—are generated in various cortical and sub-cortical structures, and form part of a widely-distributed network that we argue is superior to more classical approaches in neurolinguistics that rely mostly on a fronto-temporal circuit. keywords: phrase structure, oscillation, syntax, frequency-coupling, language. 1 Introduction It is beyond dispute that members of our species, barring the most severe pathologies or environmental circumstances, have the cognitive capacity to ∗ We are indebted to David Poeppel for invaluable comments and advice. This work was made possible through a Marie Curie International Reintegration Grant from the European Union (PIRGGA-2009-256413), research funds from the Fundaci´o Bosch i Gimpera, a grant from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (FFI-2013-43823-P), a grant from the Generalitat de Catalunya (2014-SGR-200), and an FI-fellowship from the Generalitat de Catalunya. 1 acquire grammatical systems of great internal complexity. At the heart of this capacity lies a process that one can call “Phrase Structure building”. This process takes elementary units as its input and organizes them into nested sets. It is this process that leads to the dictum that words in sentences are not mere beads on a string. A major challenge for us is that unlike phonological representations, which are linked to perceptual units, syntactic representations rely on mind-internal, self-generated cognitive inputs. Over thirty years of intensive research on a wide range of languages have made it clear that this Phrase Structure Building capacity (hereafter, PSBC) is not subject to variation (Boeckx, 2014). It underlies the construction of every sentence in every language, even if each language exhibits distinct morphophonological properties that “dress” phrases in many ways, thereby providing the major source of linguistic diversity. Put another way, PSBC can to a significant extent be kept separate from cross-linguistic considerations pertaining to variation and change. One can even go further and argue that traditional grammatical conceptions that take language-specific units like “words” to provide instructions to build phrases are wrong, and that instead, lexical items are the expressions or outputs of syntactic structures (Hale and Keyser, 1993, Halle and Marantz, 1993, Boeckx, 2014). In others words, PSBC provides the scaffolding for language-specific morphological elaborations. The goal of this paper is to offer a theoretical model of how this invariant aspect of our grammar-forming capacity may be implemented in brain terms. We have chosen to focus on PSBC, as opposed to more general notions such as ‘syntax’ because along with Ben Shalom and Poeppel (2008) we think that traditional research areas in linguistics should not be expected to map neatly onto brain units, be they areas, regions, or elementary networks. Rather, the focus should be on processes that ultimately can be decomposed into primitive and generic operations of the sort the brain is known to perform. Thus, our approach to ‘language’ fully agrees with the ‘divide-and-conquer’ perspective advocated by Schaafsma, Pfaff, Spunt, and Adolphs (2015) for other cognitive traits like “Theory of Mind”. These authors are right to stress that standard cognitive units do not permit easy downward translation to more basic processes such as those studied in neuroscience, and if taken as starting points only serve to exacerbate the granularity mismatch problem highlighted by Poeppel and Embick (2005), Embick and Poeppel (2014). The divide-and-conquer approach has recently yielded significant results in evolutionary studies grounded in comparative cognitive considerations (Ravignani et al., 2014), and we think that it could prove equally fruitful in bridging the gap between mind and brain. In addition, the divide-and-conquer approach aligns well with recent attempts in theoretical linguistics to approach components of the human language faculty “from below” (Chomsky, 2007), which also facilitates the formulation of 2 linking hypotheses between fields. An immediate consequence of this divideand-conquer approach is that it forces to adopt a new perspective on how to ground cognition in brain function. In the context of language, this meshes well with the numerous calls to go beyond the classical Broca-Lichtheim-Wernicke model (Poeppel et al., 2012, Poeppel, 2014, Fedorenko and Thompson-Schill, 2014, Hagoort, 2014). 2 Decomposing Phrase Structure Building Although already more appropriate than notions like ‘syntax’, ‘Phrase Structure Building’ itself is not a single, atomic concept. We claim that at least 4 distinct sub-processes must be distinguished if PSBC is to be mapped onto brain operations. We should point out at the outset that these sub-processes receive different names in different theoretical traditions, but we think that on the whole the recognition of these four characteristics is relatively theoryneutral. The first sub-process we dub ‘atomization’. It sets the stage for what is perhaps the most distinctive aspect of linguistic cognition. In principle, any two “conceptual” units can be combined into a phrase in the linguistic domain. Of course, in practice, languages impose many restrictions on this combination, filtering out many unwanted phrases. Likewise, many of these combinations don’t immediately make a lot of sense (think of colorless green ideas sleep furiously). But in theory any two units can be paired into a phrase. This is quite unlike what we find in more ‘primitive’ cognitive domains (e.g., the core knowledge systems of Spelke and Kinzler (2007)), which impose severe ‘adicity’ restrictions reminiscent of ‘chemical valences’. As has been documented by numerous experimental and comparative psychologists, non-linguistic minds are highly modular. In the absence of language, cross-modular combinations are extremely rare and unstable (Spelke, 2003, Hauser, 2009). Not surprisingly, several authors have seen in language the mechanism by which cross-modular thoughts can be formed and robustly used (Spelke, 2003, Carruthers, 2006, Boeckx, 2011, Pietroski, 2012, Reinhart, 2006, Mithen, 1996). By placing concepts in the language domain, ‘selectional’ restrictions can be lifted, and combinatorial possibilities expand dramatically, leading to creativity. The second sub-process amounts to set-formation, a term we prefer to arrays or sequences, although we will return to the notion of ‘hierarchical sequences’ at several points in this paper, especially in the context of the chunking role of the basal ganglia. Set-formation is the operation that combines linguistic units. We will refer to it as ‘combine’ in what follows. Many linguists take this combination process to be restricted to the combination of two 3 elements (Kayne, 1984, 1994). We will not provide a strong argument in favor of this position, but will simply adopt it here as the simplest case scenario. The third sub-process is one of categorization or labeling. It is the process by which a phrase acquires its identity. Phrases in language come in several varieties: verb phrases, noun phrases, and so on. Labeling is the operation by which a particular unit entering the combination process gives an entire phrase its identity. Traditionally, this is done ‘endocentrically’ or ‘from within’: one of the two units combined gives the phrase its name (Chomsky, 1970). More recently, though, it has been pointed out that labeling is more accurately thought of as an ‘exo-skeletal’ process: a phrase receives its entity based on its ‘entourage’, that is, the elements immediately surrounding it (Marantz, 2008, Borer, 2005, Boeckx, 2014). A noun phrase is a noun phrase in virtue of being surrounded by a determiner (the book), not because it contains a noun. A verb phrase is a verb phrase not because it contains a verb, but because a tense marker immediately dominates it (to book). Advocates of the exo-skeletal approach to labeling often point out that this process is transparently at work in the linguistic interpretation that speakers naturally impose on poems like Lewis Carroll’s Jabberwocky. Thanks to recognizable units like determiners, tense markers, etc., we come to identify nouns and verbs that otherwise could not be driving the labeling process, being as they are novel, unknown, and therefore a-categorial. The fourth sub-process is intrinsically tied to the third one. Labeling is monotonic in that once a phrase has been labeled and is embedded in another phrase, its identity is preserved. This monotonicity is often captured in linguistics by appealing to the notion of (strict) cyclicity. The process of labeling takes place as a sliding window of activity traverses the sentence: once categorized, a phrase is “consolidated” or stored as a chunk, and the next as-yet unlabeled structure becomes the focus of syntactic decision. 3 Phrase Structure Building and Brain Oscillations Our proposal concerning the brain implementation of the processes giving rises to phrases will be couched in terms of brain rhythms. It has long been suspected that the rhythmic fluctuations of electrical activity produced by the brain may play a role in cognition, but in recent years numerous publications have put forward specific proposals concerning how neural oscillations at different frequencies could be related to a wide range of basic and higher cognitive processes (Buzs´ aki, 2006). In the language domain perhaps the most detailed 4 an compelling model is that of Giraud and Poeppel (2012), who show that θ and γ oscillations are engaged by the multi-timescale, quasi-rhythmic properties of speech and can track its dynamics. In so doing, brain rhythms ‘package’ incoming information into units that provide the basis for representations like syllables. Outside of language, several authors have shown how brain rhythms interact with one another to provide the basic computational machinery to support functions like ‘working memory’ (Lisman, 2005, Dipoppa and Gutkin, 2013, Roux and Uhlhaas, 2014). Buzs´aki (2010) goes so far as to claim that brain oscillations provide the foundational framework for a neural ‘syntax’, understood as “a set of principles that govern the transformation and temporal progression of discrete elements into ordered and hierarchical relations”. We are quite aware that not every issue has been solved in the domain of brain rhythms, but we feel quite confident that the quantity of works consulted [see Supplementary Material] provides a solid basis for the claims put forth in this section. The rhythms we will implicate to capture the processes that make up PSBC will be α, β, γ, and θ. We will claim that these rhythms interact in such a way as to yield the fundamental operations of PSBC. In addition to the cortex, we will recruit subcortical structures to generate some of these rhythms: the thalamus for the α band, the basal ganglia for the β band, and the hippocampus for the θ band. The existing literature offers evidence for associating the generation of these rhythms with these brain structures [see Supplementary Material], although they rarely assign them a fundamental function in language (but see Theofanopoulou and Boeckx (To appear)). In part this is due to the fact that neurolinguistics continues to be cortico-centric. But it is also due to the fact that most neuroscientists think of language in very concrete terms: words, sounds, etc. Our focus here is on an aspect of language that is much more closely related to the formation of thoughts, and, as we already said, is relatively separate from the morpho-phonological substance used in languages. Not surprisingly, then, the network we envisage depart in significant ways from the traditional fronto-temporal circuit (Friederici and Gierhan, 2013), which we have argued elsewhere (Boeckx et al., 2014) has been wrongly associated with aspects of phrase structure building (Friederici, 2009), an issue we return to at the end of this article. Our network also inverts the distinction between language core and periphery (Fedorenko and Thompson-Schill, 2014), attributing to domain-general circuits the role of elementary syntactic operations. In the cognitive neuroscience literature one finds two large cortical networks that seem to us to relate to the nature of PSBC as we conceive of it: the Default Mode Network (Raichle et al., 2001) and the Multiple Demand network (Duncan, 2010). Both consist of distributed cortical regions regulated 5 in part by subcortical activity. The Default Mode Network (DMN) comprises portions of the Pre-frontal cortex, the precuneus, the posterior cingulate cortex, the inferior parietal cortex, the lateral temporal cortex. DMN activitity has been detected for passive or internally-driven tasks, as opposed to active or externally-driven tasks (Buckner et al., 2008). The Multiple Demand network (MD) also consists of a fronto-parietal circuit that has been used to capture cognitive notions like “fluid intelligence” and “complex cognition”. “Mind wandering” or “divergent (unconventional) thinking” also exploit to Frontoparietal connections, and we think that it is ultimately related to the frontoparietal expansion that gives our species’ brain its distinctive globular shape (Boeckx and Ben´ıtez-Burraco, 2014). Although often assumed to be anticorrelated networks (Fox et al., 2005), DMN and MD have been shown to be transiently coupled at the scale of the rhythms we implicate here (de Pasquale et al., 2012), which we take to confer initial plausibility to our suggestion that both networks are involved in the model we envisage here. The network we have in mind also shares properties of the global workspace model in Dehaene et al. (1998) or the ‘connective core’ in Shanahan (2012). For purposes of the proposal to come, it is crucial to exploit layer-specific properties of the neo-cortex, as distinct layers have distinct rhythmic preferences, and thus ultimately play distinct cognitive roles. Here we will rely on the distinction between supra-granular and infra-granular layers, and, following Bastos et al. (2012), associate high, γ frequency oscillations mostly with the supra granular layers, and lower frequencies (specifically, β and α) with infra granular layers. Infragranular layers connect to higher-order thalamic nuclei such as the medio-dorsal nucleus and the pulvinar, which generate a robust α rhythm (Bollimunta et al., 2011) and are crucially involved in cortico-cortical information management (Theyel et al., 2010, Saalmann et al., 2012). Infragranular layers also connect to the basal ganglia, in particular the striatum, which is implicated in sequencing and chunking procedures, as well as a process of characterization in tandem with the cortex and higher-order thalamic nuclei like the medio-dorsal nucleus (Antzoulatos and Miller, 2014). Striatal structures, as well as the medio-dorsal thalamic nucleus, have been shown to operate at the β range (Leventhal et al., 2012, Parnaudeau et al., 2013). Finally, the θ rhythm is the signature rhythm of the hippocampus and associated enthorinal cortex. Through its connections with the thalamus and the basal ganglia, we hypothesize that the hippocampus is responsible for the theta rhythm detected in anterior thalamic nuclei and reuniens, and in the ventral and dorsomedial striatum, respectively. See Figures 1 and 2 for details of the “connectome”/“dynome” we envisage. We claim that PBSC arises as the result of the interaction among these 6 various rhythms. In a nutshell, the α rhythm provides the means to embed γ activity generated in widely-distributed cortical sources (but also present in sub-cortical structures such as the basal ganglia), which essentially amounts to the combination of atomic units across modular cognitive boundaries (suboperations 1 and 2 from section 2). The cyclic consolidation or storage of partial structures amounts to the periodic embedding of γ cycles inside the hippocampus-driven θ rhythm (sub-operation 4 from section 2). We hypothesize that for this γ–θ embedding to take place, γ activity must be decoupled from α activity, a process that is achieved through the action of thalamic reticular nucleus. Crucially, for this γ–θ pairing to lead to successful cognitive interpretation, it must be accompanied by a labeling process (sub-operation 3 from section 2), which in oscillatory terms is achieved by the slowing down of γ activity to the β frequency, and the subsequent coupling of β and α. See Figure 3 for a schematic representation of our mapping hypothesis. Let us spell out each claim in what follows, beginning with sub-operation 1 from section 2. Atomization is accomplished by α-embedded neural assemblies oscillating at γ in supragranular layers of the cortical regions of DMN. This is consistent with claims in the literature such as the formation of “words” in “neural syntax” (Buzs´ aki, 2010); the binding of features into coherent objects (Bosman et al., 2014); the local nature of the operation due to conduction delays (Von Stein and Sarnthein, 2000); and the directionality of feed-forward processing attributed to the rhythm (Bastos et al., 2015). Set-formation (sub-operation 2 from section 2) is accomplished by a crossfrequency coupling mechanism between higher order thalamic nuclei, specifically the dorsal pulvinar, oscillating at α frequency (Saalmann and Kastner, 2011) and the above-described assemblies oscillating at the γ range. The function of the α frequency is consistent with the active processing hypothesis in Palva and Palva (2011); the working memory literature, where the α rhythm binds visuo-spatial elements (Roux and Uhlhaas, 2014); the coexistence of α and γ signals in task-relevant regions of working memory models (Honkanen et al., 2014) and its modulation of local gamma amplitude (Roux et al., 2013, Saalmann et al., 2012). The set-formation operation just described could be regulated by activity of the thalamic reticular nucleus, which would move higher-order thalamic nuclei such as the pulvinar from a ‘burst” firing mode that would wake-up the transient cortical nodes of the network (Womelsdorf et al., 2014), to a second, tonic firing mode that would strengthen the dialog among the nodes of MD. Crucially for us, we take α activity in higher-order thalamic nuclei to go beyond the traditional inhibitory function associated with that frequency in lower-level, perceptual nuclei (Palva and Palva, 2011, Klimesch, 2012, Theofanopoulou and Boeckx, To appear). Labeling (sub-operation 3 from section 2) is accomplished by one basal 7 ganglia-thalamic-cortical loop, likely crossing the dorsolateral striatum, disinhibiting the thalamic medio-dorsal nucleus, by means of the β rhythm, retaining in working memory one of the objects generated by sub-operation 1. We claim that the basal ganglia select and hold one of the above γ-supported items, which allows it to stay coupled to the set-forming α rhythm for a longer period than other γ assemblies momentarily coupled to θ (sub operation 4). The retained γ rhythm must be slowed down to β frequency due to conduction delays that are unavoidable in the wider neural population recruited in the model envisaged here. (The distinction we introduce here between the role of the β-band and the θ-band may well correspond to the function of shortterm vs. working memory, although we leave a detailed examination of this possibility for the future, as the literature on memory systems is so complex that we cannot adequately survey it here.) Such labeling process thus leads us to distinguish two different elements as a function of the rhythms that sustain them: γ and β objects. This is consistent with the anatomical and oscillatory boundaries between supra-granular and infra-granular layers (Bastos et al., 2012) and their direction of information flow (feed-forward and feedback; Bastos et al. (2015), Miller and Buschman (2012)). It is also consistent with the different rhythms that sustain objects as a function of their complexity (Honkanen et al., 2014). There is a sense in which the system generates two kinds of ‘labels’, as in exoskeletal approaches in linguistics: a ‘procedural label’ (serving as an instruction to interpret neighboring elements), and a more ‘declarative label’, associated with traditional categories like nouns, verbs, and adjectives. This procedural/declarative distinction is often associated with the basal ganglia and the hippocampus. In fact, we hypothesize that this result is achieved when basal ganglia θ and hippocampal θ rhythms get synchronized, as shown in decision periods in various tasks (Tort et al., 2008, DeCoteau et al., 2007). Our use of the β frequency is consistent with the notion of top-down control we assume is required for labeling (Chan et al., 2014), and fits well with the idea that MD links attentional episodes in a hierarchy (Duncan, 2013). It also meshes well with the idea that β rhythm is associated with the sustainment of status quo (Engel and Fries, 2010), as well as with claims in the working memory literature that β holds information (Martin and Ravel, 2014, Engel and Fries, 2010, Parnaudeau et al., 2013, Tallon-Baudry et al., 2004, Deiber et al., 2007, Salazar et al., 2012). Ultimately, we think that the β frequency fulfills the role of non-terminal symbols in early computational models of generative grammar (Chomsky, 1957). Sub-operation 4 from section 2 consists of the desynchronization of the items from the set-forming α rhythm, and their subsequent synchronization with a θ oscillation generated by the hippocampal complex. Concretely, we 8 point to the thalamic reticular nucleus as a key element in the desyncrhonization of oscillations by means of local thalamic inhibition, along the lines of Huguenard and McCormick (2007). We also hypothesize a possible function of the median raphe nucleus in the final stage of the operation (Vertes et al., 2004). The periodicity of the sub-operation under discussion is naturally given by the cross-frequency phase-phase 2:1 coupling of α and θ (Buzs´aki, 2006). Incidentally, we think that it is this periodicity that gives its very meaning to the notion of ‘cycle’ attached to linguistic processes. The involvement of the hippocampus in our model is consistent with its widely-connected nature (de Pasquale et al., 2012) and claims that it is in service of other systems (Rubin et al., 2014). Our use of the θ frequency is consistent with claims concerning its use in the storing of items in working memory (Roux and Uhlhaas, 2014). The cross-frequency coupling of θ and α we defend here has already been recognized in the attention literature (Song et al., 2014), where this coupling controls the multi-item sampling in which θ dominates alternating periods of α. It may also shed light over the sequential/parallel debate about multi-items with attentional search (Dugu´e et al., 2014). Indeed, we think that the α rhythm plays an important role in suppressing distracting information during working memory encoding and maintenance, which lies at the heart of the intersection between working memory and attention. To a significant extent, PSBC relies on generic, conserved brain rhythm mechanisms (Buzs´ aki et al., 2013), and are therefore neither language-, nor human-specific. In our opinion, both species- and cognitive-specificity arise from the context in which these operations take place. In particular, the globularity of our species, associated with parietal expansion, certainly led to an expansion of the pulvinar and a concomitant reduction of the portion allocated to it that connects with the occipital lobe, itself reduced in anatomically modern humans (Boeckx and Ben´ıtez-Burraco, 2014, Pearce et al., 2013). Plausibly, this expansion of the pulvinar, along with a more central location of higher-order nuclei in the brain as a whole, led to a more efficient connectivity pattern across widely-distributed cortical areas, reducing “spatial inequalities” (Salami et al., 2003) in other species’ brains that prevent the formation of the “necessary symmetry” (Bastos et al., 2015) and “temporal equidistance” (Vicente et al., 2008) required to couple rhythms over widely-distributed networks. In this case, we believe that this anatomical reconfiguration played a key role in allowing for cross-modular thoughts to be robustly established and put to use. 9 4 Conclusion Needless to say, the model offered here remains to be tested experimentally. But we think that in addition to offering a biologically plausible linking hypothesis between cognitive science and neuroscience, it may provide a useful point of departure to understand cognitive deficits across a wide range of mental disorders, for which we have an increasing amount of information couched in oscillatory terms (Buzs´ aki and Watson, 2012). We also believe that some of the grammatical constraints identified in the theoretical linguistic literature may receive a natural interpretation in terms of the model presented here. Indeed, the literature on brain frequency coupling routinely mentions bottleneck effects that arise from the narrow windows of opportunities that wave-cycles offer, or the limited patterns of oscillations that local structures can sustain. In independent work we examine how the frequency-couplings put forward here may capture some of the basic restrictions found cross-linguistically, with special attention to ‘local’ patterns of exclusion known as “anti-locality” or “identity avoidance” (Richards, 2010, Boeckx, 2014). As already pointed out above, the neurobiological architecture proposed here departs from traditional thinking about language and its implementation in the brain. But we wish to stress that we regard some of the betterestablished claims in neurolinguistics to complement our approach. For instance, although we question the claim that “syntax” crucially relies on Broca’s region (Friederici, 2009), we recognize that Broca’s region plays a crucial role in processing hierarchical representations (specifically, hierarchical sequences, in the sense of Fitch and Martins (2014)), as shown in Pallier et al. (2011), Ohta et al. (2013). We take Broca’s area to provide a memory stack that is independently needed to linearize complex syntactic structures (Boeckx et al., 2014) and to integrate or unify several linguistic representations (Hagoort, 2005, Flinker et al., 2015), including sound and meaning (Bornkessel-Schlesewsky and Schlesewsky, 2013). Likewise, although we do not endorse the view that the anterior temporal lobe is the locus of syntactic structure building (Brennan et al., 2012), we endorse the more nuanced conclusion that this region plays a crucial role in compositional interpretation of syntactic structures (Westerlund and Pylkk¨anen, 2014, Del Prato and Pylkk¨ anen, 2014). Indeed, our conception of PSBC leads us to take the canonical fronto-temporal language network to be an output system of the combinatorial processes we have focused on here. We think that it is likely that this network, rooted as it appears to be in primate audition (Bornkessel-Schlesewsky et al., 2015), was recruited (in the sense of Dehaene (2005), Parkinson and Wheatley (2013)) to pair sound and meaning boosted 10 up by PSBC in our species. It also bears repeating that in line with current linguistic theorizing we take the PSBC to be dissociable from phonological processing. As a result, the involvement of some of the frequency ranges we have appealed to here may not have been detected in standard neurolinguistic paradigms, which adopt too concrete a view on linguistic structures, too close to auditory processing. Such a reliance on concrete perceptual events may not provide the right detection threshholds for pure syntactic computations. Quite apart from this complementarity, we think that a major conclusion of our approach lies in the role of subcortical structures in language beyond the domain of speech (Kotz and Schwartze, 2010). We anticipate that properties once thought to be the exclusivity of the cortex will turn out to be mirrored sub cortically, as recent research indicates (Friederici, 2006, Wahl et al., 2008, Jeon et al., 2014). References Antzoulatos, Evan G, and Earl K Miller. 2014. Increases in functional connectivity between prefrontal cortex and striatum during category learning. Neuron 83:216–225. Bastos, Andre M, W Martin Usrey, Rick A Adams, George R Mangun, Pascal Fries, and Karl J Friston. 2012. Canonical microcircuits for predictive coding. Neuron 76:695–711. Bastos, Andre M, Julien Vezoli, and Pascal Fries. 2015. Communication through coherence with inter-areal delays. Current opinion in neurobiology 31:173–180. Ben Shalom, Dorit, and David Poeppel. 2008. Functional anatomic models of language: assembling the pieces. The Neuroscientist 14:119–127. Boeckx, Cedric. 2011. Some reflections on Darwin’s Problem in the context of Cartesian Biolinguistics. In The biolinguistic enterprise: New perspectives on the evolution and nature of the human language faculty, ed. A.-M. Di Sciullo and C. Boeckx, 42–64. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Boeckx, Cedric. 2014. Elementary syntactic structures. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Boeckx, Cedric, and Antonio Ben´ıtez-Burraco. 2014. The shape of the language-ready brain. Frontiers in Psychology 5:282. Boeckx, Cedric, Anna Martinez-Alvarez, and Evelina Leivada. 2014. The functional neuroanatomy of serial order in language. Journal of Neurolinguistics 32:1–15. Bollimunta, Anil, Jue Mo, Charles E Schroeder, and Mingzhou Ding. 2011. 11 Neuronal mechanisms and attentional modulation of corticothalamic alpha oscillations. The Journal of Neuroscience 31:4935–4943. Borer, Hagit. 2005. Structuring Sense (2 vols.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Bornkessel-Schlesewsky, Ina, and Matthias Schlesewsky. 2013. Reconciling time, space and function: a new dorsal–ventral stream model of sentence comprehension. Brain and language 125:60–76. Bornkessel-Schlesewsky, Ina, Matthias Schlesewsky, Steven L Small, and Josef P Rauschecker. 2015. Neurobiological roots of language in primate audition: common computational properties. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 19:142–150. Bosman, Conrado A, Carien S Lansink, and Cyriel Pennartz. 2014. Functions of gamma-band synchronization in cognition: from single circuits to functional diversity across cortical and subcortical systems. European Journal of Neuroscience 39:1982–1999. Brennan, Jonathan, Yuval Nir, Uri Hasson, Rafael Malach, David J Heeger, and Liina Pylkk¨ anen. 2012. Syntactic structure building in the anterior temporal lobe during natural story listening. Brain and language 120:163– 173. Buckner, Randy L, Jessica R Andrews-Hanna, and Daniel L Schacter. 2008. The brain’s default network. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1124:1–38. Buzs´ aki, Gy¨ orgy. 2006. Rhythms of the brain. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Buzs´ aki, Gy¨ orgy. 2010. Neural syntax: cell assemblies, synapsembles, and readers. Neuron 68:362–385. Buzs´ aki, Gy¨ orgy, Nikos Logothetis, and Wolf Singer. 2013. Scaling brain size, keeping timing: Evolutionary preservation of brain rhythms. Neuron 80:751–764. Buzs´ aki, Gy¨ orgy, and Brendon O Watson. 2012. Brain rhythms and neural syntax: implications for efficient coding of cognitive content and neuropsychiatric disease. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience 14:345. Carruthers, P. 2006. The Architecture of the Mind . Oxford: Oxford University Press. Chan, Jason L, Michael J Koval, Thilo Womelsdorf, Stephen G Lomber, and Stefan Everling. 2014. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex deactivation in monkeys reduces preparatory beta and gamma power in the superior colliculus. Cerebral Cortex bhu154. Chomsky, Noam. 1957. Syntactic structures. The Hague: Mouton. Chomsky, Noam. 1970. Remarks on nominalization. In Readings in English transformational grammar , ed. R. Jacobs and P. Rosenbaum, 184–221. 12 Waltham, Mass.: Ginn and Co. Chomsky, Noam. 2007. Approaching UG from below. In Interfaces + recursion = language? Chomsky’s minimalism and the view from semantics, ed. U. Sauerland and H.-M. G¨artner, 1–30. Mouton de Gruyter. DeCoteau, William E, Catherine Thorn, Daniel J Gibson, Richard Courtemanche, Partha Mitra, Yasuo Kubota, and Ann M Graybiel. 2007. Learningrelated coordination of striatal and hippocampal theta rhythms during acquisition of a procedural maze task. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104:5644–5649. Dehaene, Stanislas. 2005. Evolution of human cortical circuits for reading and arithmetic: The “neuronal recycling” hypothesis. In From monkey brain to human brain, ed. S. Dehaene, J.-R. Duhamel, M. Hauser, and J. Rizzolatti, 133–157. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. Dehaene, Stanislas, Michel Kerszberg, and Jean-Pierre Changeux. 1998. A neuronal model of a global workspace in effortful cognitive tasks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 95:14529–14534. Deiber, Marie-Pierre, Pascal Missonnier, Olivier Bertrand, Gabriel Gold, Lara Fazio-Costa, Vicente Ibanez, and Panteleimon Giannakopoulos. 2007. Distinction between perceptual and attentional processing in working memory tasks: a study of phase-locked and induced oscillatory brain dynamics. Journal of cognitive neuroscience 19:158–172. Del Prato, Paul, and Liina Pylkk¨anen. 2014. Meg evidence for conceptual combination but not numeral quantification in the left anterior temporal lobe during language production. Frontiers in psychology 5. Dipoppa, Mario, and Boris S Gutkin. 2013. Flexible frequency control of cortical oscillations enables computations required for working memory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110:12828–12833. Dugu´e, Laura, Philippe Marque, and Rufin VanRullen. 2014. Theta oscillations modulate attentional search performance periodically. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 26:1–14. Duncan, John. 2010. The multiple-demand (md) system of the primate brain: mental programs for intelligent behaviour. Trends in cognitive sciences 14:172–179. Duncan, John. 2013. The structure of cognition: attentional episodes in mind and brain. Neuron 80:35–50. Embick, David, and David Poeppel. 2014. Towards a computational(ist) neurobiology of language: correlational, integrated and explanatory neurolinguistics. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience 1–10. Engel, Andreas K, and Pascal Fries. 2010. Beta-band oscillations—signalling the status quo? Current opinion in neurobiology 20:156–165. Fedorenko, E., and S. L. Thompson-Schill. 2014. Reworking the language 13 network. Trends in cognitive sciences 18:120–126. Fitch, W. Tecumseh, and Mauricio D Martins. 2014. Hierarchical processing in music, language, and action: Lashley revisited. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1316:87–104. Flinker, Adeen, Anna Korzeniewska, Avgusta Y Shestyuk, Piotr J Franaszczuk, Nina F Dronkers, Robert T Knight, and Nathan E Crone. 2015. Redefining the role of broca’s area in speech. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112:2871–2875. Fox, Michael D, Abraham Z Snyder, Justin L Vincent, Maurizio Corbetta, David C Van Essen, and Marcus E Raichle. 2005. The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102:9673–9678. Friederici, Angela D. 2006. What’s in control of language? Nature neuroscience 9:991–992. Friederici, Angela D. 2009. Brain circuits of syntax. In Biological Foundations and Origin of Syntax. Str¨ ungmann Forum Reports (Volume 3), 239–252. Mit Press. Friederici, Angela D, and Sarah ME Gierhan. 2013. The language network. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 23:250–254. Giraud, Anne-Lise, and David Poeppel. 2012. Cortical oscillations and speech processing: emerging computational principles and operations. Nature neuroscience 15:511–517. Hagoort, Peter. 2005. On broca, brain, and binding: a new framework. Trends in cognitive sciences 9:416–423. Hagoort, Peter. 2014. Nodes and networks in the neural architecture for language: Broca’s region and beyond. Current opinion in neurobiology 28:136– 141. Hale, Ken, and S. Jay Keyser. 1993. On argument structure and the lexical expression of grammatical relations. In The view from Building 20: Essays in Linguistics in honor of Sylvain Bromberger , ed. K. Hale and S. J. Keyser, 53–110. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. Halle, Morris, and Alec Marantz. 1993. Distributed morphology and the pieces of inflection. In The view from building 20 , ed. K. Hale and S. J. Keyser, 111–176. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. Hauser, Marc D. 2009. The possibility of impossible cultures. Nature 460:190– 196. Honkanen, Roosa, Santeri Rouhinen, Sheng H Wang, J Matias Palva, and Satu Palva. 2014. Gamma oscillations underlie the maintenance of featurespecific information and the contents of visual working memory. Cerebral Cortex bhu263. 14 Huguenard, John R, and David A McCormick. 2007. Thalamic synchrony and dynamic regulation of global forebrain oscillations. Trends in neurosciences 30:350–356. Jeon, Hyeon-Ae, Alfred Anwander, and Angela D Friederici. 2014. Functional network mirrored in the prefrontal cortex, caudate nucleus, and thalamus: High-resolution functional imaging and structural connectivity. The Journal of Neuroscience 34:9202–9212. Kayne, Richard S. 1984. Connectedness and binary branching. Dordrecht: Foris. Kayne, Richard S. 1994. The antisymmetry of syntax . Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. Klimesch, Wolfgang. 2012. Alpha-band oscillations, attention, and controlled access to stored information. Trends in cognitive sciences 16:606–617. Kotz, Sonja A, and Michael Schwartze. 2010. Cortical speech processing unplugged: a timely subcortico-cortical framework. Trends in cognitive sciences 14:392–399. Leventhal, Daniel K, Gregory J Gage, Robert Schmidt, Jeffrey R Pettibone, Alaina C Case, and Joshua D Berke. 2012. Basal ganglia beta oscillations accompany cue utilization. Neuron 73:523–536. Lisman, John. 2005. The theta/gamma discrete phase code occuring during the hippocampal phase precession may be a more general brain coding scheme. Hippocampus 15:913–922. Marantz, Alec. 2008. Words and phases. In Phases in the theory of grammar , ed. S.-H. Choe, 191–222. Seoul: Dong In. Martin, Claire, and Nadine Ravel. 2014. Beta and gamma oscillatory activities associated with olfactory memory tasks: different rhythms for different functional networks? Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience 8. Miller, Earl K., and Tim J. Buschman. 2012. Cortical circuits for the control of attention. Current opinion in neurobiology 23:1–7. Mithen, Steven J. 1996. The prehistory of the mind . London: Thames and Hudson. Ohta, Shinri, Naoki Fukui, and Kuniyoshi Sakai. 2013. Syntactic computation in the human brain: The degree of merger as a key factor. PloS one 8:e56230. Pallier, Christophe, Anne-Dominique Devauchelle, and Stanislas Dehaene. 2011. Cortical representation of the constituent structure of sentences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108:2522–2527. Palva, Satu, and J Matias Palva. 2011. Functional roles of alpha-band phase synchronization in local and large-scale cortical networks. Frontiers in psychology 2. Parkinson, Carolyn, and Thalia Wheatley. 2013. Old cortex, new contexts: re-purposing spatial perception for social cognition. Frontiers in human 15 neuroscience 7. Parnaudeau, Sebastien, Pia-Kelsey O’Neill, Scott S Bolkan, Ryan D Ward, Atheir I Abbas, Bryan L Roth, Peter D Balsam, Joshua A Gordon, and Christoph Kellendonk. 2013. Inhibition of mediodorsal thalamus disrupts thalamofrontal connectivity and cognition. Neuron 77:1151–1162. de Pasquale, Francesco, Stefania Della Penna, Abraham Z Snyder, Laura Marzetti, Vittorio Pizzella, Gian Luca Romani, and Maurizio Corbetta. 2012. A cortical core for dynamic integration of functional networks in the resting human brain. Neuron 74:753–764. Pearce, Eiluned, Chris Stringer, and Robin I. M. Dunbar. 2013. New insights into differences in brain organization between neanderthals and anatomically modern humans. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 280:20130168. Pietroski, Paul M. 2012. Language and conceptual reanalysis. In Towards a Biolinguistic Understanding of Grammar: Essays on Interfaces, ed. A.M. Di Sciullo. John Benjamins. Poeppel, David. 2014. The neuroanatomic and neurophysiological infrastructure for speech and language. Current opinion in neurobiology 28:142–149. Poeppel, David, and David Embick. 2005. Defining the relation between linguistics and neuroscience. In Twenty-first century psycholinguistics: Four cornerstones, ed. A. Cutler, 173–189. Hillsdale, NJ:: Erlbaum. Poeppel, David, Karen Emmorey, Gregory Hickok, and Liina Pylkk¨anen. 2012. Towards a new neurobiology of language. The Journal of Neuroscience 32:14125–14131. Raichle, Marcus E, Ann Mary MacLeod, Abraham Z Snyder, William J Powers, Debra A Gusnard, and Gordon L Shulman. 2001. A default mode of brain function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 98:676–682. Ravignani, Andrea, Daniel L. Bowling, and W. Tecumseh Fitch. 2014. Chorusing, synchrony, and the evolutionary functions of rhythm. Frontiers in psychology 5. Reinhart, Tanya. 2006. Interface strategies: optimal and costly computations. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. Richards, Norvin. 2010. Uttering trees. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. Roux, Fr´ed´eric, and Peter J Uhlhaas. 2014. Working memory and neural oscillations: alpha–gamma versus theta–gamma codes for distinct wm information? Trends in cognitive sciences 18:16–25. Roux, Fr´ed´eric, Michael Wibral, Wolf Singer, Jaan Aru, and Peter J Uhlhaas. 2013. The phase of thalamic alpha activity modulates cortical gammaband activity: evidence from resting-state meg recordings. The Journal of Neuroscience 33:17827–17835. Rubin, Rachael D, Patrick D Watson, Melissa C Duff, and Neal J Cohen. 16 2014. The role of the hippocampus in flexible cognition and social behavior. Frontiers in human neuroscience 8. Saalmann, Yuri B, and Sabine Kastner. 2011. Cognitive and perceptual functions of the visual thalamus. Neuron 71:209–223. Saalmann, Yuri B, Mark A Pinsk, Liang Wang, Xin Li, and Sabine Kastner. 2012. The pulvinar regulates information transmission between cortical areas based on attention demands. Science 337:753–756. Salami, Mahmoud, Chiaki Itami, Tadaharu Tsumoto, and Fumitaka Kimura. 2003. Change of conduction velocity by regional myelination yields constant latency irrespective of distance between thalamus and cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 100:6174–6179. Salazar, RF, NM Dotson, SL Bressler, and CM Gray. 2012. Content-specific fronto-parietal synchronization during visual working memory. Science 338:1097–1100. Schaafsma, Sara M., Donald W. Pfaff, Robert P. Spunt, and Ralph Adolphs. 2015. Deconstructing and reconstructing theory of mind. Trends in cognitive sciences 19:65–72. Shanahan, M. 2012. The brain’s connective core and its role in animal cognition. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 367:2704–2714. Song, Kun, Ming Meng, Lin Chen, Ke Zhou, and Huan Luo. 2014. Behavioral oscillations in attention: rhythmic α pulses mediated through θ band. The Journal of Neuroscience 34:4837–4844. Spelke, Elizabeth. 2003. What makes us smart? Core knowledge and natural language. In Language and Mind: Advances in the study of language and thought, ed. D. Gentner and S. Goldin-Meadow, 277–311. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. Spelke, Elizabeth, and Katherine D. Kinzler. 2007. Core knowledge. Developmental science 10:89–96. Tallon-Baudry, Catherine, Sunita Mandon, Winrich A Freiwald, and Andreas K Kreiter. 2004. Oscillatory synchrony in the monkey temporal lobe correlates with performance in a visual short-term memory task. Cerebral Cortex 14:713–720. Theofanopoulou, Constantina, and Cedric Boeckx. To appear. The central role of the thalamus in language and cognition. In Advances in biolinguistics, ed. C. Boeckx and K. Fujita. London: Routledge. Theyel, Brian B, Daniel A Llano, and S Murray Sherman. 2010. The corticothalamocortical circuit drives higher-order cortex in the mouse. Nature neuroscience 13:84–88. Tort, Adriano BL, Mark A Kramer, Catherine Thorn, Daniel J Gibson, Yasuo Kubota, Ann M Graybiel, and Nancy J Kopell. 2008. Dynamic cross- 17 frequency couplings of local field potential oscillations in rat striatum and hippocampus during performance of a T-maze task. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105:20517–20522. Vertes, Robert P, Walter B Hoover, and Gonzalo Viana Di Prisco. 2004. Theta rhythm of the hippocampus: subcortical control and functional significance. Behavioral and cognitive neuroscience reviews 3:173–200. Vicente, Raul, Leonardo L Gollo, Claudio R Mirasso, Ingo Fischer, and Gordon Pipa. 2008. Dynamical relaying can yield zero time lag neuronal synchrony despite long conduction delays. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105:17157–17162. Von Stein, Astrid, and Johannes Sarnthein. 2000. Different frequencies for different scales of cortical integration: from local gamma to long range alpha/theta synchronization. International Journal of Psychophysiology 38:301–313. Wahl, Michael, Frank Marzinzik, Angela D Friederici, Anja Hahne, Andreas Kupsch, Gerd-Helge Schneider, Douglas Saddy, Gabriel Curio, and Fabian Klostermann. 2008. The human thalamus processes syntactic and semantic language violations. Neuron 59:695–707. Westerlund, Masha, and Liina Pylkk¨anen. 2014. The role of the left anterior temporal lobe in semantic composition vs. semantic memory. Neuropsychologia 57:59–70. Womelsdorf, Thilo, Salva Ardid, Stefan Everling, and Taufik A Valiante. 2014. Burst firing synchronizes prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortex during attentional control. Current Biology 24:2613–2621. 18 Figure 1: Areas, connections, and rhythm generations 19 Figure 2: Key to Figure 1 20 Figure 3: Cross-frequency couplings mapping onto Phrase Structural relations 21

© Copyright 2025