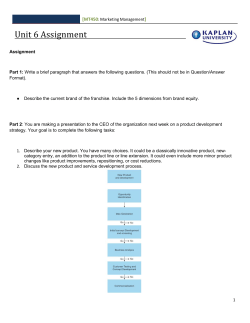

Read this report