Puberty—Timing is everything!

Puberty—Timing is everything! BELINDA PINYERD, PhD, RN Central Ohio Pediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes Services Columbus, OH WILLIAM B. ZIPF, MD, FAAP Central Ohio Pediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes Services Columbus, OH BWResearch@columbus.rr.com T: 614/840-0535 F: 614/840-0536 Page 1 of 17 ABSTRACT Puberty is a dynamic period of physical growth, sexual maturation, and psychosocial achievement that generally begins between age 8 and 14 years. The age of onset varies as a function of gender, ethnicity, health status, genetics, nutrition, and activity level. Puberty is initiated by hormonal changes triggered by the hypothalamus. Children with variants of normal pubertal development—both early and late puberty—are common in pediatric practice. Recognizing when variations are normal and when referral for further evaluation is indicated is an important skill. INTRODUCTION "When it's time to change, you have to rearrange." - Peter Brady “Puberty,” derived from the Latin pubertas meaning adulthood, is not a de novo event but a process leading to physical, sexual, and psychosocial maturation (Blondell, Foster & Dave 1999). “Puberty” differs from “adolescence” in that it is just one change (maturation of the reproductive system) that occurs during adolescence. From a biological perspective, puberty is the stage of development during which an individual first attains fertility and is capable of reproduction. Physical changes that occur during puberty include somatic growth, primary sexual organ development (gonads and genitals), and the appearance of secondary sexual characteristics (breasts and pubic hair). This paper reviews the hormonal processes responsible for inducing puberty, clinical indicators and staging of normal puberty, and psychosocial changes that accompany the physical maturation. Abnormal puberty patterns and guidelines for assessment are also reviewed. OVERVIEW: REGULATION OF PUBERTY In normal puberty, hormone secretion changes dramatically. Central to the process is a section of the brain called the hypothalamus, which produces a substance called gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH). During childhood, GnRH secretion is minimal but with the onset of puberty, secretion of GnRH is enhanced. The primary function of GnRH is to regulate the growth, development, and function of the testes in the male and the ovaries in the female. GnRH signals the pituitary gland to secrete luteinizing hormone (LH) and folliclePage 2 of 17 stimulating hormone (FSH) (also known as “gonadotropins”). In boys, LH stimulates testosterone production and FSH promotes sperm production. In girls, both LH and FSH are necessary for ovulation (rupture of follicle and release of egg from the ovary) while FSH stimulates development and maturation of a follicle in one the ovaries HORMONAL CHANGES Two processes contribute to the physical manifestations of puberty: gonadarche, the ovary or testes component of puberty; and adrenarche, the adrenal gland component of puberty. These two components may seem to occur simultaneous and be a consequence of the same phenomena, but they are separate and distinct events. Gonadarche is initiated by cells of the hypothalamus that secrete GnRH. During childhood, prior to the onset of puberty, the hypothalamus “gonadostat” is exquisitely sensitive to very low concentrations of sex steroids (androgens and estrogens). As a result, GnRH secretion is suppressed, preventing LH and follicle-stimulating hormone FSH release from the pituitary. At the end of childhood, the hypothalamus is released from the suppressive effects of the sex steroids, resulting in increased GnRH release and increased release of LH and FSH. In boys, LH stimulates testosterone production and FSH supports sperm maturation. In girls, FSH and LH stimulate ovary production of estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone, all necessary for normal menstruation (Lee, 2003). Adrenarche can occur separate from and without other signs of sexual development. The physical signs of adrenarche include the development of adult body odor, increase in testicular size, and early changes in body growth, axillary hair growth, and development of pubic hair (pubarche). Biochemically, adrenarche actually begins earlier then these signs. Studies have shown that in both boys and girls at approximately six years there is an increase production of adrenal hormones by the adrenal gland. The stimulus of adrenarche has not yet been determined, but it is separate from the onset of pituitary secretion of LH and FSH (Lalwani, Reindollar & Davis, 2003). While adrenarche begins biochemically in boys and girls at the same time, pubarche (onset of sexual hair development.) occurs 6 to 12 months later in boys than girls. In females, the signs Page 3 of 17 of adrenarche occur approximately six to 12 months after the onset of gonadarche. Physically, it is observed that shortly after the onset of the first signs of breast development (a sign of ovarian estrogen secretion), a young girl will then show signs of adrenal androgen secretion. For some girls, this sequence is reversed. Recently there is greater attention being given to this component of puberty because abnormalities in the timing of adrenarche have been shown to be associated with irregular menstrual cycles, obesity, insulin resistance, and increased risks for diabetes (Ibanez et al, 1998). In boys, the physical signs of adrenarche cannot be distinguished from the signs of gonadarche. However, the presence of pubarche, without a change in testicular size, is usually a sign that gonadarche has not yet begun. STAGING AND TIMING The pubertal sequence of events follows a certain pattern (accelerated growth, breast development, adrenarche, menarche) on average requiring a period of 4.5 years (range 1.5–6 years), with girls beginning puberty earlier than boys. In fact, most information available about the timing of puberty is for girls, as breast development and onset of menstruation (menarche) are more overt and recordable than changes in penis and testicle size in boys. Several factors in addition to gender and ethnicity impact the timing of puberty, including genetics, dietary intake, and energy expenditure. Genetic factors play an important role, as illustrated by the similar age of menarche in members of an ethnic population and in mother-daughter and sibling pairs (Meyer et al., 1991). Type of protein consumption (animal versus vegetable), amount of dietary fat, and total calories has also been related to onset of puberty (Grumbach & Styne, 2003). Puberty often begins earlier in heavier children of both sexes (Qing & Karlberg, 2001), whereas excessive exercise and psychiatric illnesses (eg, anorexia nervosa) are associated with hypogonadotropic states that can delay or arrest the onset of puberty (Warren & Vu, 2003). What specifically triggers the onset is still debated. The attainment of a particular proportion of fat mass has long been argued to be requisite for the onset of puberty in girls (Plant, 2002). Interest in this theory has intensified recently as a result of delayed puberty noted in athletic girls and girls with eating disorders (Georgopoulos et al., 1999; Warren & Fried, 2001). Page 4 of 17 Females The first visible sign of sexual maturation is the appearance of “breast buds,” generally around age 10 or 11 years of age. Full breast development takes 3 to 4 years, and is generally complete by 14 years of age. In approximately 20 percent of girls, pubic hair may be the first sign of puberty (Lalwani, Reindollar & Davis, 2003). As mentioned, pubic and axillary hair growth is primarily due to a pubertal increase in adrenal androgen (adrenarche). Over the next three years, the pubic hair becomes darker, curlier, and coarser, and spread to cover a larger area. Hair also develops under the arms, on the arms and legs, and to a slight degree on the face. The most dramatic sign of sexual maturity in girls is the onset of menstruation, which usually occurs at an average age of 12.8 years (range 11–13). Initial menstrual cycles are usually anovulatory, which is associated with irregular and often painful periods. After approximately one to two years the menstrual cycles become ovulatory and more regular (Zacharias, Rand & Wurtman, 1976. Males For boys, an increase in testicular size occurs at 9.5–13.5 yr (average 12 yr) of age, which is followed by the growth of pubic hair (Marshall & Tanner, 1970). The testes and scrotum begin to grow, and the scrotum thins, darkens, and becomes pendulous. The penis lengthens and widens, taking several years to reach full size. Sperm production coincides with testicular and penile growth, generally occurring at age 13.5–14 years. Facial hair appears about three years after the onset of pubic hair growth, first in the mustache area above the upper lip, and later at the sides of the face and on the chin. The density and distribution of hair growth varies considerably among adult men, and is correlated more with genetic factors than with hormone levels (Lee, 2003). Gynecomastia (visible breast tissue) occurs in approximately two-thirds of males some time during puberty. Onset may coincide with the onset of puberty but primarily begins at ages 13–14, before testosterone levels have reached adult levels. Most commonly it persists for 18–24 months then regresses by age 16 years (Zosi et al., 2002). Page 5 of 17 OTHER PHYSICAL AND PSYCHOLOGICAL CHANGES Growth Spurt During puberty females and males experience a growth velocity greater than at any postnatal age since infancy. The pubertal growth spurt in girls is usually observed along with the first signs of puberty (breast development and pubic hair). Peak growth occurs when breast development is between Tanner stages 2 and 3. Because girls reach peak height velocity about 1.3 years before menarche, there is limited growth potential after menarche; most girls grow only about 2.5 cm in height after menarche although there is a variation from 1 to as much as 7 cm (Grumbach & Styne, 2003). In contrast to females, the peak growth spurt in males occurs during midpuberty (Tanner stages 3–4), when testosterone levels are rapidly rising. Peak growth velocity in boys is generally at 14–15 years of age. Boys attain 28 to 31 cm of growth during the pubertal growth spurt whereas girls attain 27.5 to 29 cm of growth (Abbassi, 1998). In both males and females, the ages at menarche and peak height velocity are not good predictors of adult height because the duration of pubertal growth is the more important determinant of final height. Nonetheless, extremely early onset of puberty can diminish ultimate adult stature (Bourguignon, 1988) and prolonged delay of puberty (Hägg & Juranger, 1991) can increase stature. Acne Comedones, acne, and seborrhea of the scalp appear as a result of the increased secretion of gonadal and adrenal sex steroids. Early-onset acne correlates with the development of severe acne later in puberty. Acne vulgaris, the most prevalent skin disorder in adolescence, occurs at a mean age of 12.2 years ± 1.4 years (SD; range 9–15 years) in boys and progresses with advancement through puberty. However, acne vulgaris can be the first notable sign of puberty in a girl, preceding public hair and breast development. Mood and depression During puberty young girls frequently exhibit a negative self-image. Prepubertal boys and girls demonstrate an equal frequency of depression, although there is a more frequent occurrence in girls at stage 3. This change in the prevalence of depression appears more Page 6 of 17 related to serum sex steroid concentrations than to LH or FSH values or the physical changes of puberty (Angold, Costello & Worthman, 1998). Reports of attempted suicide increase sharply during puberty, and suicide now ranks fourth as a cause of death among 15- to 19-year-olds (Larsen, 2003). A retrospective analysis showed that adolescents who actually committed suicide during puberty had the onset of their depression in childhood or early puberty, even though the act of suicide occurred later in puberty (Rao et al., 1993). Body image An important aspect of puberty is the development of body image. Body image is a person’s inner conception of his/her physical appearance. As obvious from the previous discussion, adolescence is a time of great physical and social change. Adolescents are critical and embarrassed about their bodies during puberty, either because they are maturing too early, too late, or they are not developing according to societal’s standards of “attractiveness.” Adolescent girls appear to be particularly vulnerable to developing a negative body image, especially if their bodies develop at a pace that differs from average (Rosenblum & Lewis, 1999). Adolescents with severe body image distortions are vulnerable to developing psychiatric disorders that can have life-threatening consequences (Weinshenker, 2002). Psychosocial changes Puberty includes a profound social change from the sheltered, single-classroom environment of elementary school to the multiple classrooms and teachers of middle school (Mayer & Carter, 2003). There is exposure to new peers, often with different life experiences and behavior patterns. Risk-taking behaviors often increase, including sexual precocity and alcohol and cigarette abuse. In contrast to the concrete reasoning of childhood, the child entering puberty develops maturing abstract thought and decision-making processes. Other psychological and psychosocial changes that occur during this time include the ability to absorb the perspectives or viewpoints of others, the development of personal and sexual identity, the establishment of a system of values, and increasing autonomy from family (Remschmidt, 1994). Page 7 of 17 ABNORMAL PUBERTY Although the average age at menarche (12.8 years) has not fallen much in the past 60 years, recent data suggest that the lower age limit for normal pubertal (thelarche) onset is below the threshold of 8 years that is cited in many texts. Before 1997, premature adrenarche was defined as pubic hair developing in girls younger than 8 years old and boys younger than 9 years. However, the results of a large, cross-sectional study (Herman-Giddens, Slora & Wasserman, 1997) suggest that the onset of puberty in girls is occurring earlier than previous studies have documented, with pubic hair development appearing in white girls as young as 7 years (between 7–11 years) and in African American girls as young as 6 years (between 6–11 years). The timing of puberty is significant from a clinical standpoint given the observation that early-maturing girls and late-maturing boys show more evidence of adjustment problems than other adolescents (Graber et al., 1997). However, the definition of early puberty remains “puberty that occurs prior to age 8 years in girls and nine years in boys” (Saenger, 2003). Early The majority of children who show signs of puberty at a young age have no discernable underlying pathology, particularly if they meet other criteria (see Table 1). Some physicians order an x-ray to check that the skeletal age of the child is no more than 2.5 standard deviations (typically about 2 years) above the chronological age. For boys younger than 9 years of age who have penile enlargement, scrotal thinning, and accelerated growth, a formal evaluation is warranted. TABLE 1. CRITERIA OF BENIGN PREMATURE PUBERTY Sparse to moderate development of pubic hair Sparse or no growth of axillary hair Mild or no acne Minimal or no acceleration in growth rate Mild apocrine body order No lowering of voice No breast or testicular enlargement No clitoromegaly Source: Nakamoto, 2000 Page 8 of 17 When puberty in a young child is driven by activation of hypothalamic GnRH secretion, it is designated "central" or "true" precocious puberty (CPP). In a minority of patients, CPP arises in the setting of a central nervous system (CNS) lesion (e.g. neurofibromatosis, hydro- cephalus, CNS infection, and intracranial neoplasm with or without radiation therapy). CNS lesions seem to predispose males and females equally to early central puberty; that is, the sex ratio among patients with neurogenic CPP approximates unity. However, among children with CPP in whom there is no underlying pathology (idiopathic CPP), there is a striking sex difference, with the female to male ratio approaching 10:1 in most series (Palmert & Boepple, 2001). From a psychosocial perspective, CPP is sometimes accompanied with behavioral disturbances and symptoms of depression and/or anxiety. Dorn et al (1999) reported more withdrawal, social problems, aggression, somatic complaints, and depression in children with premature adrenarche as compared to children with “on-time” adrenarche. Precocious puberty also places a child at risk for not achieving his/her genetic height potential. The rapid maturation of the growth plate (due to sex steroid exposure) will often result in temporary acceleration of linear growth, but the accompanying early closure of growth plates results in early cessation of growth and ultimately shorter than would be expected adult height (Lee, 1999). Delayed Delayed puberty describes the clinical condition in which the physical manifestations of puberty start late (usually > +2.5 SD later than the mean). In the United States, puberty is considered to be delayed if sexual maturation has not become apparent by age 14 years in boys or age 13 years in girls. This clinical diagnosis also is made in the absence of menarche by age 16 years or in the absence of menarche within 5 years of pubertal onset. Using these criteria, approximately 2.5% of healthy adolescents will be identified as having pubertal delay (Rosen & Foster, 2001). In most cases delayed puberty is not due to any underlying pathology, but instead represents an extreme end of normal puberty, referred to as constitutional delay of growth and maturation. When puberty does begin, it is entirely normal. However, delayed puberty generally warrants referral to a pediatric endocrinologist to rule out possible genetic, hypothalamic, pituitary, gonodal, or system conditions that could be present. Page 9 of 17 PUBERTAL ASSESSMENT The standard clinical system for describing normal pubertal development and its variations is the five-stage system (called “Tanner Staging”) developed by Marshall & Tanner (1969, 1970) (refer to Tables 2 & 3). Each stage represents the extent of pubic hair growth and breast (female)/genitalia (males) development. In girls, breasts and pubic hair must be staged separately (see Table 2). Tanner stage 2 is characterized by small breast buds and "peach-fuzz" in the pubic area. During stage 3, breast buds become larger and pubic hair growth continues, but it is mostly in the center and does not extend out to the thighs or upward. Stage 4 is characterized by noticeable growth of pubic hair, underarm hair growth, and the breasts take on a "mound" form. The first menstrual period usually occurs sometime during the fourth or fifth stage. A girl has reached Tanner stage 5 when her breasts are fully formed and her pubic hair is adult in quantity and type, forming the classical upside-down triangle shape common to women. Rough estimates based upon the size and shape of the breasts (see Figure 1) along with the amount and type of hair present in the pubic area are the indexes used to track pubertal changes (Marshall & Tanner, 1969). In boys, pubertal hair distribution and testicular size must be staged separately (see Table 3). In stage 1, there is no pubic hair growth, and the penis, testes, and scrotum are about the same size and proportion as in early childhood. Stage 2 is characterized by "peach-fuzz" in the pubic area, testicular enlargement, and scrotum growth, thinning and reddening. During stage 3 the penis grows in length and pubic hair growth is darker and coarser. Stage 4 is characterized by more pubic hair, darkening of the scrotum, and increased growth of the penis. A boy has reached Tanner stage 5 when the genitalia are adult size and shape and his pubic hair has spread to the medial thighs (Marshall & Tanner, 1970). During this time the testes increase in volume from approximately 3 mL (prepubertal) to up to 20 mL (adult- hood). The Prader orchidometer, which consists of a series of increasingly larger oval beads, is the standard by which the practitioner makes a determination of the patient’s testicular size (Styne, 2002). Page 10 of 17 When a child presents with abnormal puberty, the goal of the initial assessment is to distinguish benign constitutional causes from pathologic causes. The history should focus on the child’s previous growth and development, including the timing and sequence of the physical milestones of puberty. A history of medical or surgical treatment may provide clues to an underlying pathologic condition. The family history may reveal information about a familial pattern of delayed or early puberty, as well as information about genetic disease. A physical examination should focus on evaluation of the genitalia and determination of the stage of pubertal development. A detailed growth chart is used to estimate annual growth rate (centimeters per year) and to determine if a growth spurt has occurred. When the history and/or evaluation of the child with early or delayed pubertal development suggest a pathological cause, referral to a pediatric endocrinologist is warranted. CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS Knowledge of the timing and the physical changes associated with puberty is important for pediatric practitioners. Parents and adolescents often experience anxiety when puberty is not occurring as expected, even when it occurs within the range of normal. The pediatric practitioner can allay much of that anxiety with counseling regarding the natural and normal variation of this process. A clear understanding of pubertal milestones also promotes appropriate interventions for delayed or advanced puberty when the practitioner and parents are in agreement that intervention is in the best interest of the child. Recently, changes in the timing of puberty as compared to previously published standards now make the understanding of this complex process even more important. The observation that more children are showing signs of puberty earlier places pressure upon the practitioner to differentiate the child with early but otherwise normal puberty from the child with early onset puberty as a consequence of a pathologic process. Even with normal but early-onset puberty, close observation of the temporal process is needed to adequately predict if the abnormal timing will impact final adult height. Referral to a specialist in pediatric endocrinology is indicated for patients who present with signs of early or delayed puberty. Health care for adolescents should include systematic monitoring of pubertal development and concerns in order to aggressively educate preadolescents to negotiate this period smoothly and to avoid high-risk behaviors that could have negative health and social Page 11 of 17 sequelae during adolescence and adulthood. Interventions with parents of children who present with abnormal puberty include providing anticipatory guidance, supporting parent communication strategies, and providing support and information resources (Doswell & Vandestienne, 1996; Williams, 1995). Finally, with the observation that precocious adrenarche can be an early sign of the metabolic syndrome, close monitoring for obesity, insulin resistance, acanthosis nigracans, hypertriglyceridemia, and other problems associated with the metabolic syndrome are particularly relevant when the child presents with signs of early puberty. Page 12 of 17 TABLE 2. TANNER STAGES OF FEMALE PUBERTY STAGE BREAST 1 PUBIC HAIR Only papillae are elevated. Vellus hair only and hair is similar to development over anterior abdominal wall (ie. no pubic hair). 2 Breast bud and papilla are elevated and a small mount is present; areola diameter is enlarged. There is sparse growth of long, slightly pigmented, downy hair or only slightly curled hair, appearing along labia. 3 Further enlargement of breast mound; increased palpable glandular tissue. Hair is darker, coarser, more curled, and spreads to the pubic junction. 4 Areola and papilla are elevated to form a second mound above the level of the rest of the breast. Adult-type hair; area covered is less than that in most adults; there is no spread to the medial surface of thighs. 5 Adult mature breast; recession of areola to the mound of breast tissue, rounding of the breast mound, and projection of only the papilla are evident. Adult-type hair with increased spread to medial surface of thighs; distribution is as an inverse triangle. Preadolescent Adult FIGURE 1. DIAGRAMMATIC REPRESENTATION OF TANNER STAGES I TO V OF HUMAN BREAST MATURATION From Marshall WA, Tanner JM: "Variations in patterns of pubertal changes in girls." Archives of Disease in Childhood 44:291-303, 1969; USED WITH PERMISSION??? Page 13 of 17 TABLE 3. TANNER STAGES OF MALE PUBERTY STAGE GENITAL STAGE 1 Testes, scrotum, and penis are about the same size and proportion as those in early childhood. Vellus over the pubes is no further developed than that over the abdominal wall, i.e., no pubic hair. 2 Scrotum and testes have enlarged, and there is a change in the texture of scrotal skin and some reddening of scrotal skin. There is sparse growth of long, slightly pigmented, downy hair, straight or only slightly curled, appearing chiefly at base of penis. 3 Growth of the penis has occurred, at first mainly in length but with some increase in breadth. There has been further growth of the testes and the scrotum. Hair is considerably darker, coarser, and more curled and spreads sparsely over junction of pubes. 4 The penis is further enlarged in length and breadth, with development of glans. The testes and the scrotum are further enlarged. There is also further darkening of scrotal skin. Hair is now adult in type, but the area covered by it is smaller than that in most adults. There is no spread to the medial surface of the thighs. 5 Genitalia are adult in size and shape. No further enlargement takes place after stage 5 is reached. Hair is adult in quantity and type, distributed as an inverse triangle. There is spread to the medial surface of the thighs but not up the linea alba or elsewhere above the base of the inverse triangle. Preadolescent Adult Page 14 of 17 PUBIC HAIR STAGE REFERENCES Abbassi V. (1998). Growth and normal puberty. Pediatrics, 102, 507-511. Angold A., Costello E.J., & Worthman C.M. (1998). Puberty and depression: the roles of age, pubertal status and pubertal timing. Psycholological Medicine, 28, 51-61. Blondell R.D., Foster M.B., & Dave K.C. (1999). Disorders of puberty. American Family Physician, 60, 209-224. Bourguignon J.P. (1988). Linear growth as a function of age at onset of puberty and sex steroid dosage: therapeutic implications. Endocrine Reviews, 9, 467-488. Dorn L.D., Mitt S.F., & Rotenstein D. (1999). Biopsychological and cognitive differences in children with premature vs. on-time adrenarche. Archives Pediatric Adolescent Medicine, 153, 137-146. Doswell W.M., & Vandestienne G. (1996). The use of focus groups to examine pubertal concerns in preteen girls: initial findings and implications for practice and research. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing, 19(2), 103-120. Georgopoulos N., Markou K., Theodoropoulou A., Paraskevopoulou P., Varaki L., Kazantzi Z., Leglise M., & Vagenakis A.G. (1999). Growth and pubertal development in elite female rhythmic gymnasts. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 84(12), 4525-4530. Graber J.A., Lewinsohn P.M., Seeley J.R., &Brooks-Gunn J. (1997). Is psychopathology associated with the timing of pubertal development? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(12), 1768-1776. Grumbach M.M., & Styne D.M. (2003). Puberty: Ontogeny, neuroendocrinology, physiology, and disorders. In Larsen P.R. (Ed.), Williams textbook of endocrinology, 10th ed, (pp 1115-1200). St. Louis: Saunders. Hägg U., & Juranger J. (1991). Height and height velocity in early, average and late maturers followed to the age of 25: a prospective longitudinal study of Swedish urban children from birth to adulthood. Annals of Human Biology, 18, 47-56. Hamann A., & Matthaei S. (1996). Regulation of energy balance by leptin. Experimental and Clinical Endocrinology and Diabetes, 104, 293-300. Herman-Giddens M.E., Slora E.J., Wasserman R.C., et al. (1997). Secondary sexual characteristics and menses in young girls seen in office practice: a study from the Pediatric Research in Office Settings Network. Pediatrics, 99, 505-512. Ibanez L., Potau N., Francois I., & de Zegher F. (1998). Precocious pubarche, hyperinsulinism, and ovarian hyperandrogenism in girls: relation to reduced fetal growth. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 83, 3558-3562. Page 15 of 17 Lalwani S., Reindollar R.H., & Davis A.J. (2003). Normal onset of puberty have definitions of onset changed? Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America, 30(2), 279-286. Lee P.A. (1999). Central precocious puberty: An overview of diagnosis, treatment, and outcome. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics, 28(4), 901-908. Lee P.A. (2003). Puberty and its disorders. In F. Lifshitz F (Ed.), Pediatric endocrinology, 4th ed (pp. 221-237). New York: Marcel Dekker. Marshall W.A., & Tanner J.M. (1969). Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 44(235), 291-303. Marshall W.A., & Tanner J.M. (1970). Variations in the pattern of pubertal changes in boys. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 45(239), 13-23. Mayer C., & Carter J. (2003). Puberty advice for year 6 and 7 boys and girls. The Journal of Family Health Care, 13(3), 70-72. Meyer J.M., Eaves L.J., Heath A.C., & Martin N.G. (1991). Estimating genetic influences on the age-at-menarche: a survival analysis approach. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 39, 148154. Nakamoto J.M. (2000). Myths and variations in normal pubertal development. Western Journal of Medicine, 172(3), 182-185. Palmert M.R., & Boepple P.A. (2001).Variation in the timing of puberty: clinical spectrum and genetic investigation. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 86, 2364-2368. Plant T.M. (2002). Neurophysiology of puberty. Journal of Adolescent Health, 31(6 Suppl), 185191. Qing H., & Karlberg J. (2001). BMI in childhood and its association with height gain, timing of puberty, and final height. Pediatric Research, 49, 244-251. Rao U., Weissman M.M., Martin J.A., & Hammond R.W. (1993). Childhood depression and risk of suicide: a preliminary report of a longitudinal study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 32, 21-27. Remschmidt H. (1994). Psychosocial milestones in normal puberty and adolescence. Hormone Research, 41(suppl 2), 19-29. Rosen D.S., & Foster C. (2001). Delayed puberty. Pediatrics in Review, 22(9), 309-315. Rosenblum G.D., & Lewis, M. (1999). The relations among body image, physical attractiveness and body mass in adolescence. Child Development, 70, 50-64. Page 16 of 17 Saenger P. (2003). Precocious puberty: McCune-Albright syndrome and beyond. Journal of Pediatrics, 143(1), 9-10. Styne D.M. (2002). The testes: disorders of sexual differentiation and puberty in the male. In M.A. Sperling (Ed.), Pediatric endocrinology (pp. 565-628). Philadelphia: Saunders. Warren M.P., & Fried J.L. (2001). Hypothalamic amenorrhea. The effects of environmental stresses on the reproductive system: a central effect of the central nervous system. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America, 30(3), 611-629. Warren M.P., & Vu C. (2003). Central causes of hypogonadism–functional and organic. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America, 32(3), 593-612. Weinshenker N. (2002).Adolescence and body image. School Nurse News, 19(3), 12-16. Williams J.K. (1995). Parenting a daughter with precocious puberty or Turner syndrome. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 9(3), 751-752. Zacharias L., Rand W.M., & Wurtman R.J. (1976).A prospective study of sexual development and growth in American girls: the statistics of menarche. Obstetrical and Gynecological Survey, 31(4), 325-337. Zosi P., Karakaidos D., Triantafyllidis G., Milioni N., Franglinos P., & Karis C. (2002). Natural course of pubertal gynecomastia. Endocrine Abstracts, 4, P18. Page 17 of 17

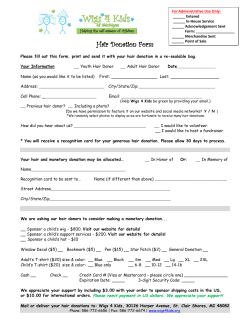

© Copyright 2025