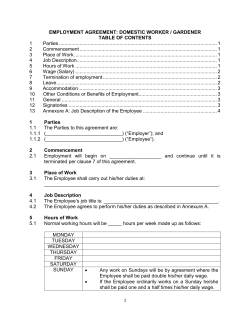

Wages, prices, and living standards in China, 1738- Title