Lost in translation?

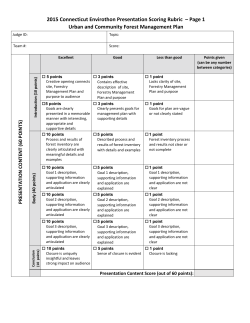

university of copenhagen Lost in translation? How project actors shape REDD+ policy and outcomes in Cambodia Pasgaard, Maya Published in: Asia Pacific Viewpoint DOI: 10.1111/apv.12082 Publication date: 2015 Document Version Preprint (usually an early version) Citation for published version (APA): Pasgaard, M. (2015). Lost in translation? How project actors shape REDD+ policy and outcomes in Cambodia. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 56(1). 10.1111/apv.12082 Download date: 06. jul.. 2015 bs_bs_banner Asia Pacific Viewpoint, Vol. 56, No. 1, April 2015 ISSN 1360-7456, pp111–127 Lost in translation? How project actors shape REDD+ policy and outcomes in Cambodia Maya Pasgaard1 Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management. Email: mapa@ign.ku.dk Abstract: Forest protection policies to Reduce Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation (REDD+) are currently being implemented by international donors, governments and conservation agencies across the developing world aiming for reduction of greenhouse gases while ensuring fair distribution of benefits. This paper draws on a case study in northern Cambodia to analyse how conservation practitioners and the local forest management committees engaged in implementing REDD+ actively translate and influence the policy and its implementation in accordance with their respective interests through particular communication strategies. When assessing project progress and outcomes, the conservation practitioners involved in implementing projects show an interest in emphasising positive project assessments by downplaying potential project complications, and by primarily communicating with pro-REDD+ members of the local communities. Powerful actors in the local forest management committees adopt the conservation rhetoric of these practitioners; at the same time, they can interpret and control local access to resources to their own advantage. By doing so, they can ensure continued support, while not necessarily representing all community members or sharing benefits equally. The processes and consequences of this policy translation in a REDD+ arena are discussed and compared with existing dominant trends in environment and development policies. Keywords: Cambodia, policy actors, pro-poor policy, REDD+, social assessments, translation Introduction Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation (REDD+) is a multi-donor climate mitigation programme which seeks to create and trade the financial value of carbon stored in forests as a means of reducing forest emissions and mitigating climate change (UN, 2009a; World Bank, 2011). The United Nations and the World Bank with their UN-REDD+ programme and Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF), respectively, are the main international organisations promoting and supporting REDD+ activities, along with a wide range of other institutions (Cerbu et al., 2011). Besides the intended carbon offsets, proponents of REDD+ promise social co-benefits in terms of jobs, livelihoods, land tenure clarification, enhanced participation in decision-making 1 Present address: Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management. and improved governance from REDD+ (UN, 2009b). However, the social implications and potential co-benefits from REDD+ are of a complex and multidimensional nature (Ghazoul et al., 2010; Hirsch et al., 2011). REDD+ as a global climate change and development policy faces daunting challenges (e.g. Hansen et al., 2009; Ghazoul et al., 2010; Dooley et al., 2011; Hirsch et al., 2011; Thompson et al., 2011; Pasgaard, 2013). Key concerns include insecure tenure arrangements, inequitable distribution of benefits (e.g. Hansen et al., 2009; Sunderlin et al., 2009; Blom et al., 2010; Sikor et al., 2010; Springate-Baginski and Wollenberg, 2010; Milne and Adams, 2012; Pasgaard and Chea, 2013), the risk of policy failure due to the involvement of multiple actors with diverse interests (e.g. Di Gregorio et al., 2012), a failure to acknowledge the inherent complexities at the community level (e.g. Hirsch et al., 2011), inadequate assessment of socio-political challenges © 2015 Victoria University of Wellington and Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd doi: 10.1111/apv.12082 M. Pasgaard (Pasgaard, 2013) and the risk of elite capture of benefits from various forest protection programmes (e.g. Larson and Ribot, 2007; Andersson and Agrawal, 2011). These are serious concerns that could undermine the prospects of reaching the anticipated social and pro-poor benefits promoted in the REDD+ policies. Because REDD+ is a relatively new programme, studies of how the policy objectives compare with the practical achievements at the project level are only beginning to emerge (e.g. McCarthy et al., 2012; CIFOR, 2013). While this emerging research consistently emphasises how new relationships, intermediary actors and novel alliances shape conservation schemes such as REDD+ (see Di Gregorio et al., 2012; Fairhead et al., 2012; Funder et al., 2013), no studies have yet addressed policy translations within these new (re)configurations. Policy translation is developed in detail below, but refers simply to the processes through which policies are interpreted and communicated through different actors and networks. This paper draws on recent empirical research in Cambodia to identify how REDD+ practices and impacts are translated through policy processes. The paper primarily focuses on the translational activities taking place between the conservation practitioners responsible for the implementation of the REDD+ project, and the local forest management committees as the community representatives. The emphasis on these two groups of actors is chosen because their relations and activities profoundly shape REDD+ on the ground, and on the basis of access to informant networks during data collection phase. Policy translation is also taking place among other relevant actors in the policy chain, such as local Nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) and the international donors. They are referred to in order to provide a broader perspective on the chains of actors involved in the translation of the REDD+ policy from global to local levels and back. The Oddar Meanchey REDD+ project in Cambodia was selected as a case study by the author to investigate how REDD+ impacts and practices are translated through project stages. As other tropical developing countries throughout Southeast Asia and beyond engaged with 112 REDD+, the country faces massive deforestation challenges and is undergoing dramatic changes in land use and development (e.g. Hall et al., 2011). The Oddar Meanchey province, which has historically been densely forested, is suffering from a high demand for timber and agricultural and settlement land resulting in a high rate of decline in forest cover (Bradley, 2009). The REDD+ demonstration project is at a relatively advanced stage, having been initiated in 2008 with carbon credits now on the market (Pact, 2012). This means that the project actors are defined and established, and that several studies and assessments of the project have been conducted, such as a recent household survey (Blackburn, 2011) and studies of deforestation drivers (e.g. Poffenberger, 2009; Pact, 2010). This paper examines and goes beyond these assessments to advance an understanding of how particular groups of actors shape REDD+ through policy translation. The paper is structured as follows. The second section presents the theoretical framing of the paper and its focus on policy translation in the context of REDD+. The third section presents the methods and case study including a brief outline of the Oddar Meanchey REDD+ demonstration project. Drawing on empirical findings, this project is analysed in two ways in the fourth section. First, in relation to the roles and interests of a selection of the key actors engaged in the REDD+ project; and second, by examining the mode in which the policy is translated and circulated through this chain of actors. The last section discusses and compares the findings with existing research in conservation and development policies. Theoretical and conceptual frame Various institutions and stakeholders operating at local, regional and global scales are often involved simultaneously in the same projects. These actors are neither completely neutral nor passive in the processes of shaping and implementing the policy. This paper centres primarily on the actors engaged directly in the practical implementation of a policy, namely the conservation agency and the local forest management committee. Translation of REDD+ between these policy actors, both with regard to the policy implementation and its achievements, is © 2015 Victoria University of Wellington and Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd Lost in translation? the focal point of investigation within the theoretical and conceptual frame outlined below. The idea of ‘translation’ provides an underlying theoretical entry point for the subsequent analysis of the empirical data. Translation, development brokers and friction In his ‘model of translation’, Latour (1986) describes how a chain of actors can actively shape and change power – or any other ‘token’1 – in accordance with the actor’s own project and interests. In that way, each of the people in the chain shape the token according to their different projects, rather than simply resisting it or transmitting it in its entirety like in a diffusion process. In the same line of thinking, Lewis and Mosse (2006) unfold the translation model in a development policy context. These authors argue that an actor-oriented approach allows for the study of intermediary actors or ‘brokers’, who can be seen as intermediaries between development institutions and local society. Such brokers operate at the interfaces of different world views and knowledge systems, and are important in negotiating roles, relationships and representations. In turn, the translation or meanings through development brokers produces project realities (Lewis and Mosse, 2006). Several other scholars have studied how different actors can shape a policy and its outcome, some emphasising the ‘frictions’ (Tsing, 2005) or ‘slippery spaces’ (Zink, 2013) that occur when the diverging interests of actors conflict or coexist, as the policy moves across actor networks. For instance, Tsing (2005) emphasises the unexpected and unstable aspects of local/global interactions and encounters in globe-crossing capital and commodity chains, such as development and conservation projects, which REDD+ arguably is a part of. These heterogeneous and unequal encounters can lead to new arrangements of culture and power, she argues, and this ‘friction’ gets in the way of the smooth operation of global power. In conservation programmes, collaborations and unexpected alliances can arise, creating new interests and identities, but not to the benefit of all. For example, community leaders might intentionally misrepresent a given situation to conservation experts and learn the rhetoric of conservation in order to be recognised and effective in their advocacy (Tsing, 2005: 199). Thus, these kinds of translations or frictions through different actors or brokers are essential in determining the practical outcome of a policy and how the policy shapes and evolves. Besides the introduced concepts of translation, brokers and friction, other metaphors and examples are used to describe the way implementation of a policy is modified through chains of actors. In a study on environmental change in Kenya, Adams (1996) describe how ideas ‘move from the planning room to field project’ (Adams, 1996: 156, emphasis added) by percolating down through the bureaucratic system, and how ideas sediment down gradually and adapt themselves to precedent thinking. This paper will primarily use the term ‘translation’ from this point forward to describe how a policy is shaped through a chain of actors. Importantly, indicating a one-way and downward direction of this translation from policy to practical outcomes (Adams, 1996) does not address how the policy itself can be reshaped through actors’ translation. Including influential actors at the local level as brokers or a ‘conservation elite’ and not merely as beneficiaries or participants is also essential (Funder et al., 2013). Taken together and exemplified with the case from Cambodia, this paper examines the two-directional translation processes or activities; the upward translation in which policy practice and achievements are translated by community representatives through conservation practitioners to reach donors, and the downward translation of the policy rhetoric and objectives resulting in unintended outcomes (summarised in Fig. 2). Environmental subjects and hidden transcripts In order to enable a more detailed examination of the specific translational activities which occur between conservation practitioners and local forest managers, two supplementary concepts are included in the theoretical frame of this paper, namely environmentality (Agrawal, 2005) and transcripts (Scott, 1990). In his muchcited writings on ‘Environmentality’, Agrawal (2005) describes the creation of ‘environmental subjects’ – people who come to care about the environment as a response to changes in © 2015 Victoria University of Wellington and Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd 113 M. Pasgaard ownership when a new policy is introduced. He argues that villagers’ beliefs change when they become involved in practices of environmental regulation, such as monitoring in community forestry. For instance, the rhetoric of these new environmental subjects becomes resonant with the prevailing conservation rhetoric, which favours forest protection and matches policy objectives. Agrawal (2005) emphasises the significant variation within villages in how individual villagers see forests and protect them. Furthermore, subjects might not make themselves in ways desired by the ‘gaze of power’. Arguably, conflicting desires for personal gain and interests still matter, which is an important aspect in the policy translation between these new environmental subjects and the conservation practitioners. Thus, in a study of REDD+ policy translation, it is relevant to investigate the use of certain conservation rhetoric oriented towards the making of environmental subjects, their interests and their relationships with other powerful actors. Agrawal (2005) refers to James Scott’s work on domination and resistance, in particular on how autonomous views in local communities about the prevailing social order are invisible to outsiders. Scott (1990) describes the public transcript as open interaction, as the roles played by disguise and surveillance in power relations. In contrast to the public transcripts are the hidden transcripts, the off-stage performances specific to a given social site and a particular set of actors, which do not find public expression. Scott (1990) describes and exemplifies the frontier between the public and the hidden transcripts as a class struggle, ‘a zone of constant struggle between dominant and sub-ordinate’ (Scott, 1990: 14), and he argues that analysis based exclusively on public transcript will likely conclude that the subordinate groups are willing, even enthusiastic, partners in that subordination and endorse the given terms. While the relationship between conservation practitioners involved in REDD+ implementation and a local forest management committee might not constitute a classic class struggle between a dominant and subordinate group, the concepts of public and hidden transcripts are useful for understanding the translation process in what is still a power-laden context. Thus, the concepts of environmentality and transcripts are relevant 114 for the examination of the upward translation of policy achievements, which are to be assessed by the conservation practitioners in order to (dis-)continue or adapt policies. Specifically, it is critical to establish not only the extent to which new environmental subjects come to actually care about the forest they are responsible for, but also to establish whether their rhetoric about conservation is a staged public transcript to satisfy powerful visitors and match policy objectives. Financial aspects As the last part of the theoretical frame, the present paper emphasises the interplay between policy translation and finance. Financial aspects and incentives are omnipresent in the REDD+ policy arena and affect the interactions between the actors, to whom the policy constitutes a resource, a profession, a market, a stake or a strategy (see de Sardan, 2005; see Goldman, 2005). The organisations involved in implementing a project, for example, have an incentive to portray project success over failure as a means of securing continued funds and influence (Saito-Jensen and Pasgaard, in press). In a process of actively not learning from experience, certain lessons from project evaluations and assessments are readily recognised and incorporated in future initiatives, while other lessons are selectively avoided or even suppressed (Hulme, 1989). Finance, therefore, shapes policy translation, with financial aspects continuously surfacing along a policy chain where actors communicate. The link between the two is also expressed in the particular conservation rhetoric or project ‘language’ spoken by local brokers in the presence of visitors (see also Agrawal, 2005). For these brokers, who act as accountable representatives for the target population, the ability to speak the language development institutions and donors expect is an entry ticket into an international development network and with it the promise of funds (de Sardan, 2005). The use of this language – and other translational means and channels – plays a central role in the reproduction of a policy or a project, when it moves along a chain of actors. Examination of this conservation rhetoric, as well as of project assessments and conflicts, is a key part of the empirical approach © 2015 Victoria University of Wellington and Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd Lost in translation? Table 1. Overview of the groups of actors included in the study of policy translation in REDD+ Actor Local villagers Forest Management Committee Local NGO Conservation agency Donor institution Main interests Data sources Daily subsistence, mainly from agriculture Access to benefits from forest protection Benefits from forest protection, such as forest products (legal or illegal), donor support (employment or direct financial support) and carbon funds Influence over decision-making Continued project funds for staff employment Influence on project functioning and project assessments Successful project, i.e. reach policy objectives Continued support from donors for staff Build capacity and start new projects (more funds) Successful projects, i.e. reach environmental and social policy objectives Continued support and funding from donor countries Semi-structured interviews Field observations Semi-structured interviews Key informant interviews Observations at CF federation meeting Document analysis Observations at CF federation meeting Interviews and conversations with conservation agency staff Document analysis Interviews and informal conversations with project staff Observations at CF federation and project validation meetings Document analysis Observations at international donor-attended seminars, workshops and meetings CF, community forestry; NGO, Non-governmental organisation. to this study of policy translation among actors in REDD+ as described below. Empirical approach and study area At the centre of this research are semi-structured interviews and documentary analysis, coupled with observations of the project site (summarised in Table 1). The paper primarily draws on a field study in the Oddar Meanchey province conducted in 2011 consisting of 114 semistructured interviews with local villagers covering five different community forestry (CF) sites and eight villages in total. The CFs included in the study are Chhouk Meas (one village studied), Prey Srorng (two villages), Samaky (two villages), Sangkrous Preychheu (one village) and Sorng Rokavorn (two villages). The respondents were mainly relatively poor farmers, who worked their crop fields, ran a small business at the roadside, produced charcoal or worked for hire. An equal number of men and women were interviewed and more than half of the respondents were members of the CF their village belonged to. A few village headmen, CF leaders and a Buddhist monk were interviewed as well. The open-ended questions in the interviews mainly concerned the causes of deforestation and the challenges encountered by CF/REDD. In addition to these interviews, primary data consist of eight interviews with other stakeholders, namely government officials from the Forest Administration and project staff from international aid agencies involved with forest conservation and development programmes. Primary data also consist of notes and minutes from meetings, including a CF federation meeting with the presence of all CF leaders and a REDD+ validation meeting between the conservation agency and a thirdparty consultancy firm. Furthermore, data are supplemented by field observations, observations at meetings and seminars, as well as various secondary data sources (newspaper articles, reports, legal documents, scientific papers, etc.). As an analytical entry point, these data are structured around two specific forms of translation between the actors in a policy chain. Firstly, the conservation rhetoric or ‘project language’ is examined through the analysis of interviews, written documents, project meetings, etc. (see also de Sardan, 2005). Secondly, various project assessments are examined, such as social assessments and the third-party validation meeting, in order to study the translation, reproduction and extension of the project through such project evaluations (see Hulme, 1989; Goldman, 2001, 2005; Mosse, 2001). Besides the examination of the conservation rhetoric © 2015 Victoria University of Wellington and Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd 115 M. Pasgaard and project assessments, conflicts among groups of actors are identified and studied, as a way of revealing their strategies and logics (de Sardan, 2005). Together, these three points are examined by employing a range of methodological strategies and data sources (described above). Overall, these methods are employed with the aim of following the processes, practices, discourses, technologies or networks that construct and deconstruct policy (see Peck and Theodore, 2010). In practice, this means connecting ‘the places of policy invention not only with spaces of circulation and centers of translation, but also with the netherworlds of policy implementation’ (Peck and Theodore, 2012: 24). Penetrating below the official line and staged performances to reveal the ‘hidden transcripts’ (Scott, 1990), and to expose actors’ economic incentives, personal strategies, failures and contradictions (de Sardan, 2005) requires a high level of trust. Also, access to the relevant policy actors and networks is a necessity. This access was gained and extended through existing networks, collaboration and exchange of knowledge, personal follow-up interviews and timing of data collection. For instance, observing at a validation meeting and REDD+ seminar was only made feasible through mutual collaboration and by being present at the right time and place. Empirical data, policy documents and secondary sources were analysed using QSR Nvivo 9 software QSR International Pty Ltd., Doncaster (Victoria), Australia, Version 9, 2010 for qualitative analyses in order to identify prevailing rhetoric, common narratives and themes. The case study area in Oddar Meanchey Oddar Meanchey province is one of the country’s poorest and most remote, located at the northern Thai-Cambodian border, where political and armed border conflicts have played out over past years (Bradley, 2009). Multiple complex factors at the local, national and regional scale drive deforestation in the province, such as agricultural expansion, Economic Land Concessions, forestland encroachment and illegal logging, as well as land speculation and firewood consumption (see Bradley, 2009; Poffenberger, 2009). The influx of poor, landless people to forest-rich resource frontiers, such as 116 Oddar Meanchey, also plays an important role in competition for land and resources (see USAID, 2004; Thul, 2011). Weak forest sector governance with inadequate forest law enforcement and low institutional capacity (UN-REDD, 2010) underlies and aggravates the problem. For instance, high levels of corruption and violence in the forestry sector play a role (Le Billon, 2002; Global Witness, 2007), reflected in land conflicts and continued granting of concessions in Oddar Meanchey leading to disputes over land (Roeun and Vrieze, 2011; Soenthrith, 2011). The REDD+ project In an attempt to protect the remaining forests in Oddar Meanchey from a deforestation rate of more than 2% decline in forest cover2 per year, 13 CFs have been established and supported by international NGOs and by legal frameworks provided by the Government of Cambodia (RECOFTC, 2010). The CFs are managed by the local communities as a response to increasing levels of deforestation and insecure forest tenure (Bradley, 2009). These CFs provide the platform for the country’s first REDD+ demonstration project initiated in 2008, followed by the approval of Cambodia’s National UN-REDD Program a few years later (UNREDD, 2010). The REDD+ project in Oddar Meanchey CFs is expected to provide financing and development to the communities through carbon credits generated from forest protection and regeneration. The 13 CFs currently participating in the Oddar Meanchey CF/REDD+ project comprise 58 villages and cover an area of approximately 68 000 ha of forestland. An international NGO, an international carbon company, and two local NGOs facilitate the preparation and implementation of the CF/REDD+ project in partnership with the government (the Forestry Administration) (see Fig. 1). Specifically, the Forestry Administration is the seller of carbon on behalf of Royal Government of Cambodia. The Forest Administration participates in project design, and is responsible for implementation and daily administration of project activities. The conservation agency (international NGO) assists the Forest Administration with coordination of project actions, participates in project design, and in the facilitation between various stake- © 2015 Victoria University of Wellington and Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd Lost in translation? Forest Administration • Government agency • Implementing organisation Administration and design of project activities, support forest protection, seller of carbon Conservation Agency Carbon company • International NGO • Implementing partner Project design, activities and assessments • Private organisation • Technical implementing partner Project design, carbon calculations and marketing Two local NGOs • Implementing partners Consultations, project actions and assessments in the communities Communities of Oddar Meanchey Province • Community Forestry Federation • Implementing partner Daily management Figure 1. Organisational diagram indicating roles and responsibility of the main project partners (based on Terra Global, 2012). Lines indicate the connections between the organisations: The FA, conservation agency and local NGOs work directly with the communities (represented by the CF Federation of CF leaders and the management committees) during field visits, project activities, meetings, etc. The carbon company supports the development of all carbon market preparatory work and negotiations. The conservation agency and the community representatives are at the centre of analysis in the study presented in this paper as indicated with bold outlines. NGO, non-government organisation holders including training of local communities, stakeholder consultation and integration, such as designing and conducting social assessments and forest inventories. The carbon company also participates in the project design and provides technical assistance, as well as marketing project carbon credits. One of the local NGOs supports implementation project actions in the field, such as training local communities, and stakeholder consultation and integration (Terra Global, 2012). For the practical everyday management of the CF, the Community Forestry Management Committees (CFMCs) have the main responsibilities and decision-making power, including recruitment and fund management, and these committees are elected by CF members for five-year terms (Royal Government of Cambodia (RGC), 2003). The objective of the project is to reduce emissions of approximately 8.3 million metric tons of carbon dioxide over 30 years, earning more than $50 million under an assumed price of $7 per ton carbon dioxide (Bradley, 2012). In order to reach this objective, the project needs to reduce the complex drivers of deforestation and forest degradation previously outlined, which threatens the forests protected under CF/REDD+ in the province. The main project activities include reinforcement of forest tenure, community-based forest protection, fire prevention, introduction of fuel-efficient cook stoves and agricultural intensification (Terra Global, 2012). The Forestry Administration stipulates that a minimum of 50% of net income from the sale of carbon credits, after project costs are covered, is expected to flow directly to local communities (Bradley, 2009). Both monetary and non-monetary benefits from the protection of the forest (e.g. from carbon sales and in terms of NTFPs, respectively) are to be shared among the community members. One of the main policy documents, the Project Design Document (see Terra Global, 2012: 163), calls for a pro-poor approach to benefit sharing to specifically ensure that the poorest households receive substantial benefits from the project. © 2015 Victoria University of Wellington and Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd 117 M. Pasgaard Actors shaping a policy through translation The analysis of policy translation among project actors in Oddar Meanchey REDD+ has three components. Firstly, based on empirical findings, I describe and categorise groups of actors in the policy chain in terms of their interests and strategies. Secondly, based on an analysis of project language and assessments, a conceptual model is suggested that illustrates and explains the routes and forms of translation between these actors in the policy chain. In this model, the two-directional mode in which such translation shapes policy outcomes and feeds back into policy making is emphasized. Thirdly, the actors and the suggested mode of policy translation among them are discussed and compared with existing dominant trends in conservation and development policies. Taken together, the analysis shows how project actors shape and translate the REDD+ policy and its outcomes according to their own interests, exemplified by the strategic use of conservation rhetoric and selective learning from project assessments. Actors engaged in Oddar Meanchey REDD+ demonstration project Based on empirical findings, five groups of actors in the Oddar Meanchey REDD+ policy network are briefly described here (see also ‘The REDD+ project’ section above). These five groups – the local villagers, the forest management committees, a local NGO, the international conservation agency and the donor institution – were selected for analysis due to their project relevance and their levels of interactions. The following analysis mainly focuses on the project level actors and in particular the translation activities that take place between the conservation agency and the local forest management authority (Community Forestry Management Committee (CFMC)). The local villagers are mainly agriculturalists who rely on agricultural land. Their main interest is their daily subsistence and survival. Only a few households have land titles recognised by the authorities and the risk of land grabbing by commercial companies or influential elites is high. Interviews show that many villagers are recent migrants, who were displaced, landless 118 and living in poverty. Most villagers are unaware that the REDD+ project exists and what it is about. While some villagers engage in CF/REDD+ activities, the empirical findings reveal how others are excluded from enjoying the benefits of forest protection due to various constraints, such as poor health, lack of resources, distance to the forest or due to deliberate exclusion by the CFMC, who controls forest access and management decisions (see also Pasgaard and Chea, 2013; see also Howson and Kindon, 2015). The local CFMCs are dominated by the wealthier households in the communities and by existing social relations. Broadly, their main interests in the CF/REDD+ project are the forest benefits, the expected ‘carbon cash’ for income and development, and donor support for monitoring activities. As explained by a CF leader: From what I experience about CF establishment, there are many benefits from forest management. The land and forest has been managed and many people can access to products like mushroom, resin, rattan, wild vegetables, etc. From my point of view, because I’ve participated in trainings, I expect to get benefits in cash from carbon project to my CF development. Some of the villagers have limited education; therefore it was very hard for them to understand about the project (pers. comm., 2011, 13 July). It appears that a common strategy to secure and attract more financial support is related to monitoring activities. The biggest challenge is the lack of financial support to the patrol team, because they have some immediate needs and they spend a lot of time on patrol and rotate regularly. Because if we didn’t do like this, the forest area will be lost and the project also going to fail (pers. comm., 2011, 2 July, CF leader). These are genuine concerns and the general desire to support forest protection appears reasonable. However, according to some villagers, their management committee and leaders are involved in illegal harvesting of timber in the CF they themselves manage (see Pasgaard and Chea, 2013), while at the same time they © 2015 Victoria University of Wellington and Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd Lost in translation? require support for forest monitoring (see also Funder et al., 2013). A local NGO is involved in the dissemination and assessment activities in Oddar Meanchey. For instance, the NGO conducted a comprehensive household survey used as part of the social assessment and to estimate secondary emissions and ‘leakage’ from the project area (Blackburn, 2011). The local NGO is tied by strong kin relations and must have an interest in continued employment from project funds in order to maintain income and influence on project implementation and monitoring. The conservation agency is the main implementing partner together with the government agency, and has a range of responsibilities (see ‘The REDD+ project’ section). The main interest of the conservation agency is to ensure implementation of the project in order to secure continued funding for it (and future projects), and for its own international and local staff. In order to reach these goals, criteria for project validation and registration on the carbon market must be fulfilled. The large multilateral donor institution for REDD+ support (together with the World Bank) is UN-REDD+. The UN has an interest in a successful REDD+ programme. The organisation wants to reach the ambitious environmental and social co-benefits expected from REDD+, such as ‘equitable pro-poor outcomes’ (the United Nations REDD programme 2011– 2015: 13–14) in order to satisfy the individual donor countries (decision-makers and the public), whose support and funds they ultimately rely on. The actors and their respective interests are summarised in Table 1. Translation of REDD+ policy In this section, I explore the routes and processes of translation between the actors introduced above (Fig. 2 below). Two types of translation activities are identified – those relating to conservation rhetoric and to those relating to project assessments. These are supplemented with observations of how acts of translation are related to benefit sharing and conflicts within local communities. The conservation rhetoric The use of a specific conservation rhetoric or ‘project language’ was evident among the most active CF members and leaders: for instance, by referring to the concept of leakage: I am worried about the REDD project, if the forest outside the CF area were cleared, it will impact on REDD by causing the carbon emitted to increase around my CF area (pers. comm., 2011, 2 July, CF leader). The project language is also reflected in the technical terminology and common development phrases and objectives adopted by some CF members: [The carbon project] is helpful – when credits come it will be shared among the CF and support patrolling. Benefit sharing from credits goes to all members, [this is] more transparent and fair. We will use it for fish pond, pig and chicken farm, school and hospital for the whole village. It is hard to say when the benefits will be delivered. If no funding – [I am] not satisfied, but will still conserve the forest for future generations (pers. comm., patrol team leader, 2011, 30 June, emphasis added). A similar rhetoric is adopted by a CF leader, when asked about the requirements and responsibilities of being a CF member: Whoever loves and is willing to protect the forest for their next generation. We didn’t force them to become a member, it based on their voluntariness. A person who is from 18 years old up can be a CF member, without favoritism and we do not mind about any [political] party involvement (pers. comm., 2011, 13 July, emphasis added). Despite these promising statements resonating with REDD+ policy objectives, interviews among community members showed how the actual decisions and regulations concerning sharing of forest and carbon benefits are interpreted and practised quite differently across the individual CFs. Examples of collection of fees from villagers to extract resources and be CF members are common, along with several accusations of social exclusion of certain members by the CFMC, leading to biased access to benefits among villagers, together with accusations of illegal forest activities by these committees and leaders: © 2015 Victoria University of Wellington and Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd 119 120 Conservation agency Donor level (UN) Conservation rhetoric Active members adopt and use project language The CFMC communicates directly with conservation practitioners Project assessment Validation of the project PERCEPTION of Cambodia as “leading country” Conflict Accusations of illegal activities among CFMCs Low representativeness Figure 2. The figure summarises the forms and examples of translational activities shaping the policy through the chain of actors. As highlighted, the diagram emphasises the contrast between the social objectives and the perceptions at donor level on the one hand, and the realities in the local communities on the other hand. CF, community forestry; NGO, Non-governmental organization OUTCOME: Inequitable distribution of benefits Local community level (villagers) Interpretation of policy Inclusion/exclusion of members Biased access to benefits Community Forestry Management Committee (CFMC) Project assessments Selectively target active CF members Conducted via local NGO (household survey) Policy rhetoric Win-win narratives Social and pro-poor OBJECTIVES M. Pasgaard © 2015 Victoria University of Wellington and Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd Lost in translation? [I] used to be active [in CF], but stopped being called to patrols and other activities five months ago . . . A CF fee was collected by the CF team leader, [it is] based on kindness, on what you can spare . . . I paid 5000 riel per month – don’t know the use [of the money] . . . [I] didn’t get any benefits – other members do – [there is] favoritism of a closed group of related patrollers who keep the information and benefits to themselves (pers. comm., 2011, 5 July). [I] used to be [CF member], but now I am not allowed because I am old and can do no CF activities . . . As a member I paid fee to the CF. The amount of fee depend on the member, the ‘kindness of their heart’ – whatever they can spare. Collected per month – the CF management asked village chief to collect [the money]. These and other statements by different villagers tell strikingly similar stories about exclusions, apparently random and off-the-record collection of fees, and illegal activities in the CF, all quite contrary to statements about conservation, transparency, equity, membership requirements and non-favouritism expressed by higherlevel CF members echoing CF regulations (see RGC, 2003) and REDD+ policy documents (see Terra Global, 2012). Assessment of the project Three specific aspects of project assessment became apparent from the case study, namely in relation to: (i) social assessments in local communities, (ii) validation of the REDD+ project for its registration on the carbon market; and (iii) the accumulation of such assessments at donor level. Firstly, social assessments of the demonstration project in Oddar Meanchey are required as prescribed in the project design document (Terra Global, 2012). Besides a household survey among project participants and nonparticipants, the periodic social assessments include Participatory Rural Appraisals (PRAs) and focus groups among a ‘targeted, purposive sample of CFMC members and project participants’ (p. 138, emphasis added). This package of so-called ‘community impact monitoring’ is mainly the responsibility of the conservation agency and it is an important criterion for the validation of the project. In practice, however, the household survey contained several major flaws and lacked important questions (Blackburn, 2011: 100 forward). For instance, sections on attitudes and behaviours related to the project, as well as on changes in land tenure security, social capital and access to resources, were not included in the survey. Also, questions concerning patrolling and trading of timber were also missing. Furthermore, the actual data collection in the communities was outsourced to the local NGO, which raised several concerns about the reliability and accuracy of the survey (see Blackburn, 2011: 5–8). In sum, the PRA and other impact monitoring activities, such as field visits, workshops, training and meetings, primarily target the community members who engage actively in the carbon project, while the non-members or less active members seem to be included in assessments to a lesser extent. Secondly, a REDD+ meeting was held between the conservation agency, representatives from the carbon trade company and the government agency, and a third-party consultancy firm, with the purpose of validating the project. At the meeting, the REDD+ proponents (the conservation agency, the government agency and the carbon company) addressed specific challenges for REDD+ in Oddar Meanchey in a particular way, making them appear less critical and more manageable, as described below. For example, potential conflicts within communities were disregarded with reference to the participatory processes of consultation, stakeholder engagement and conflict resolution (pers. comm., 2011, 16 August, conservation agency representatives). Similarly, the potential detrimental effects of Economic Land Concessions on the project were addressed as a ‘leakage problem beyond what REDD+ can deal with, [it is] much more efficient to intensify agriculture’ (pers. comm., 2011, 16 August, carbon company representative). This is in line with the main project activities suggested in the policy documents, which explicitly excludes Economic Land Concessions from the carbon calculations (Terra Global, 2012: 36). A third aspect of project assessments concerns the donor level. Here the information about the specific challenges and outcomes for © 2015 Victoria University of Wellington and Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd 121 M. Pasgaard REDD+ programme countries accumulates, affects policy-making and is disseminated to the wider public. For example, the head of the UN-REDD secretariat was keynote speaker at a REDD+ seminar in Copenhagen in autumn 2011. When questioned broadly about success stories in REDD+, he mentioned Cambodia as a ‘leading country’ (pers. comm., 2011, 14 September). The donor level completes the circle of translation from policy objectives to perceptions of project success and will be further described below. A two-directional translation of the REDD+ policy? The actors, their rhetoric and project assessments can be summarised as a twodirectional mode of translation, with examples of how actors can shape the policy to their own advantage (Fig. 1). In short, the analysis above shows how the social objectives of the policy, such as pro-poor benefit sharing, are disregarded in the project assessments, for which the conservation agency is responsible. These policy objectives and regulations are further translated and interpreted by the local forest management committees in their own favour, as they control the everyday access to benefits and decision-making in practice. Local villagers thereby risk an inequitable distribution of benefits and they lack representation in the forest management committees. These committees instead communicate directly with the conservation agency using their powerful positions and conservation rhetoric to influence project assessments and decisions about funding. Besides building their project evaluations on communication with the management committees, the conservation agency communicates project challenges and outcomes in a way that eases project validation and continued funding. In the end, this translation across actors of the REDD+ policy could contribute to the donor perception of Cambodia as ‘a leading country in REDD+’ and sustain and confirm the policy objectives. Discussion Multiple actors with diverse interests The empirical findings from the REDD+ demonstration project in Oddar Meanchey show 122 how the rhetoric of local forest management resonates with the prevailing conservation rhetoric on forest protection for future generations and carbon emissions (e.g. leakage), and matches REDD+ policy objectives of fair and transparent distribution of benefits. On the outside, the villagers actively engaged in forest protection have become ‘environmental subjects’, who truly care about the forest (Agrawal, 2005). However, the research in Oddar Meanchey shows how the public transcript expressed rhetorically in official ‘staged’ interactions (Scott, 1990), such as an interview with a foreign researcher, might not tell the whole story. While the public transcript and the conservation rhetoric used by these environmental subjects portray deference and consent, this is possibly only a tactic (see Scott, 1990). A hidden transcript appears to lie beneath with resistance to REDD+ in terms of unequal benefit sharing and illegal forest activities, which take place beyond the eyes of visitors. The ‘conservation elite’ is able to strengthen monitoring practices to their own advantage, and to some extent move them beyond the reach of government agencies and conservation and development practitioners (Funder et al., 2013). As mentioned, these elites can selectively adopt specific environmental idioms and turn them to their own advantage in struggles over resource control, and they thereby affect the implementation or outcome of an intervention (Leach and Mearns, 1996). Such a scenario can play out if conservation fieldworkers blindly accept the local accounts as indisputable in their assessments, because the power relations shaping the encounters between locals and conservation agency are invisible to the latter (Leach and Mearns, 1996). A similar situation arises if complicated struggles over land and forest resources within the community are simply ignored by the project staff (Milne and Adams, 2012). Indeed, the everyday regulations in and decisions about forest management are influenced far more directly by the local management committee networks than by state officials or conservation agencies. The social exclusion of peripheral members and the low representativeness found in the case study, as well as the lack of information and attention to stakeholder processes reflected by the inadequate social assessments, emphasise the risk © 2015 Victoria University of Wellington and Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd Lost in translation? of procedural inequity in REDD+ (see McDermott et al., 2013; Marion Suiseeya and Caplow, 2013). Facilitated by contextual inequities in the form of existing underlying power structures, these procedural equities surface in the case study as a critical part of the distributional inequity within communities, where benefits are biased towards the certain wellconnected members, who are active in forest patrols or are part of the committee network (see also Pasgaard and Chea, 2013). While these high-level community members do protect the forest and control illegal practices, they also calculate their own potential gains and losses in a context of new institutional arrangements (Agrawal, 2005). As development brokers, this conservation elite negotiates the terrain between the forest conservation agencies and other community members (Funder et al., 2013). They have a rhetoric competence in their ability to speak the language the conservation agency and donor experts expect; a language which they never use in their everyday lives except in the presence of visitors seen a priori as potential donors. This project language, in turn, is not only an entry ticket into an international network and development funds; it also plays a central role in the reproduction of the project itself (de Sardan, 2005). With regard to the interests of the local forest management committees, who seek to maintain and expand their resources and influence, the social assessments of the project can also be to their advantage. In particular, an examination of social assessments in Oddar Meanchey shows that the household survey has several flaws and shortcomings, as it ignores or misses out on information which is important and relevant from an equity perspective. Other social assessment activities, including training and workshops, often selectively target the more active members and management committees, so that other community members cannot raise their voices with equal strength. In addition, the validation of the project through a third-party consultancy firm is eased by making it appear more feasible and equitable, portraying communities as homogenous units fighting external threats. According to Li (2007), conservation agencies and other NGOs ‘sell’ the term community in order to access donor-funded projects, as their institu- tional survival depends upon successful projects and further donor funds. They are part of the development and conservation industry, which is a time-consuming, and yet potentially lucrative, business opportunity (Goldman, 2005), where funds funnel to Northern scientists, consultants and firms shuttling back and forth between the developing country and their home countries (Goldman, 2001). However, this presents a twofold paradox for the conservation practitioners. They rely on external funding and their campaigns must therefore appeal to a wide public and donor audience; this ironically often serves to reinforce the stereotyped images the very same institutions may wish to challenge (see Leach and Mearns, 1996). At the same time, the conservation agency relies on the engagement of local power structures in the remote rural villages, even at the risk of legitimising and becoming reliant upon these networks (Hughes, 2001). In turn, this can cause problematic connections and encounters when a policy moves across diverse actor networks in development and conservation programmes (Tsing, 2005), as exemplified with the REDD+ demonstration project in Oddar Meanchey. Lastly, at the donor level, policy objectives are formulated and policy outcomes are synthesised and disseminated to the wider public and the scientific community. Open to speculation is whether UN-REDD’s perception of Cambodia as a ‘leading country’ in REDD+ is partly a result of the upward translational activities across other actors during validation meetings and the selective learning from community assessments, facilitated by the conservation rhetoric mastered by the community members active in forest management. If the direction of the argument is reversed, then the failure to respect social standards can also be the result of the combined pressure from REDD+ countries resisting stringent environmental and social standards, and key donors wanting quick disbursement of funds (Dooley et al., 2011: 32). Donors need to distribute funding in order to secure next year’s budget (Zink, 2013), and thus the development industry can be accused of creating its own demand (Goldman, 2005). These two lines of arguments are not mutually exclusive, but rather mutually reinforcing. © 2015 Victoria University of Wellington and Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd 123 M. Pasgaard Translation among actors shaping REDD+ policy This paper summarises how various actors contribute to the overall translation of the REDD+ policy from the donor level to local villagers and back (Fig. 2). The translation across the chain of actors occurs in a two-directional mode, or in an ‘orbital manner’, where local traces are fed back into policy audits and negotiations at the international level (Zink, 2013: 172). As such, the art of eco-governance circulates and expands through multiple sites of encounter, leading to new modalities of power and knowledge, while the modern eco-rational subject and the environmental state are being mutually constituted (Goldman, 2001). This globally circulating knowledge also creates new gaps, even as it grows through the frictions of encounters (Tsing, 2005: 13). A gap in REDD+ between policy objectives and procedural and distributional injustices on the ground is exemplified with the Oddar Meanchey REDD+ project in Cambodia. These empirical findings also show how policies rarely travel as complete packages; rather, they move in bits and pieces, and arrive as policies already-intransformation instead of replicas (Peck and Theodore, 2010). This is shown with regard to the social objectives of pro-poor benefit sharing, which are re-shaped and interpreted at the local level by the CFMC. With examples of selective project assessments and rhetorical adaptations, the case study exemplifies how such policy objectives and regulations can mutate and morph as they are shaped by multidirectional forms of cross-scalar and inter-local policy mobility (Peck and Theodore, 2010). Concluding remarks In more general terms, there seems to be a major gap between concepts and forest policy initiatives developed and promoted at international and national levels on the one hand, and their application at the regional and local levels on the other hand (Rametsteiner, 2009). This paper argues that such policies do not reach their well-meaning intentions because various project actors with diverse interests translate the policies and the practical achievements of the policies in a self-reinforcing manner. And as shown, the 124 responsibility for conducting social assessments intended to identify the gaps between policies and their practical achievements, including potential community impacts, lies with the conservation agency, who rely on project success. The conservation agency outsources project surveys to the local NGO, who is also interested in continued project funds, and targets project assessments towards the forest management committee. This same committee is also the authority in control of forest monitoring activities and decisions. In sum, the conservation agency and these local partners are not impartial in the process; rather, stakes and interests are high, and these actors depend on the success of and funds from the project they monitor and assess. The inclusion of an external and neutral body that would assist with developing and conducting project assessments, and who is financially independent of project success, might be required to minimise the translation of the policy objectives by influential actors. The essential first step, however, is to acknowledge the complex social networks and communication patterns within and between a community and conservation practitioners, and to avoid uniform project approaches that do not take into account these networks and practices (see Hoang et al., 2006). As suggested by Funder et al. (2013: 218): ‘we need to move beyond simplistic assumptions of community strategies and incentives in participatory conservation and allow for more adaptive and politically explicit governance spaces in protected area management’. Overall, a more nuanced perspective with increased emphasis on the various actors engaged in REDD+, their interests and rhetoric, as well as their roles in project assessments, is needed to prevent the well-intentioned objectives of REDD+ being lost in translation. Acknowledgements The author would like to thank Lily Chea, Christina Ender and Phat Phanna for their valuable support and company during the fieldwork in Oddar Meanchey, and thanks also to the residents of the study sites for their help in participating in interviews. A special thank you goes to the Community Forestry Program staff of Pact Cambodia, and in particular Amanda Bradley for her collaboration and constructive feedback. © 2015 Victoria University of Wellington and Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd Lost in translation? Finally, the author gratefully acknowledges the comments provided by the issue editors, and the financial assistance from WWF/Novozymes that made the research fieldwork possible. This research is part of the project entitled Impacts of Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation and Enhancing Carbon Stocks (I-REDD+), and also contributes to the Global Land Project (GLP). Notes 1 Besides power, a token can also be a claim, an order, an artefact (Latour, 1986) or a policy, as examined here. 2 Refer to data where forest is defined as land spanning more than 0.5 ha, with trees higher than 5 m and a canopy cover of more than 10%, or trees able to reach these thresholds in situ (GRAS A/S, 2010). References Adams, W.M. (1996) Irrigation, erosion & famine, Chapter 9, in M. Leach and R. Mearns (eds.), The lie of the land: Challenging received wisdom on the African environment. Oxford: James Currey. Agrawal, A. (2005) Environmentality – Community, intimate government, and the making of environmental subjects in Kumaon, India, Current Anthropoloogy 46: 161–190. Andersson, K. and A. Agrawal (2011) Inequalities, institutions, and forest commons, Global Environmental Change: Human and Policy Dimensions 21: 866–875. Blackburn, T. (2011) Oddar meancheay REDD+ project. Report on 2010 household survey. Pact-Cambodia. Phnom Penh, Cambodia: Pact. Blom, B., T. Sunderland and D. Murdiyarso (2010) Getting REDD to work locally: Lessons learned from integrated conservation and development projects, Environmental Science & Policy 13: 164–172. Bradley, A. (2009) Communities & carbon. Establishing a community forestry-REDD project in Cambodia. Retrieved 26 March 2014, from Website: http:// www.focali.se/filer/Communities%20and%20Carbon .pdf Bradley, A. (2012) Does community forestry provide a suitable platform for REDD? A case study from Oddar Meanchey, Cambodia, in L. Naughton-Treves and C. Day (eds.), Lessons about Land Tenure, Forest Governance and REDD+. Case studies from Africa, Asia and Latin America (pp. 61–72). Madison, WI: UW-Madison Land Tenure Center. Cerbu, G.A., B.M. Swallow and D.Y. Thompson (2011) Locating REDD: A global survey and analysis of REDD readiness and demonstration activities, Environmental Science & Policy 14: 168–180. CIFOR (2013) REDD+ subnational initiatives. Fact sheet on the Global Comparative Study on REDD+. Bogor, Indonesia: Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR). Retrieved 26 March 2013. from Web- site: http://www.cifor.org/online-library/browse/view -publication/publication/4261.html de Sardan, J-P.O. (2005) Anthropology and Development: Understanding Comtemporary Social Change. Zed Books. Di Gregorio, M., M. Brockhaus, T. Cronin and E. Muharrom (2012) Politics and power in national REDD+ policy processes, in A. Angelsen, M. Broackhaus, W.D. Sunderlin and L. Verchot (eds.), Analysing REDD+. Challenges and choices. Bogor, Indonesia: Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR). Dooley, K., T. Griffiths, F. Martone and S. Ozinga (2011) Smoke and mirrors: A critical assessment of the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility. Report by FERN and Forest Peoples Programme, February 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2014, from Website: http://www.fern.org/sites/ fern.org/files/Smokeandmirrors_internet.pdf Fairhead, J., M. Leach and I. Scoones (2012) Green Grabbing: a new appropriation of nature?, Journal of Peasant Studies 39(2): 237–261. Funder, M., F. Danielsen, Y. Ngaga, M.R. Nielsen and M.K. Poulsen (2013) Reshaping conservation: The social dynamics of participatory monitoring in Tanzania’s community-managed forests, Conservation & Society 11(3): 218–232. Ghazoul, J., R.A. Butler, J. Mateo-Vega and L.P. Koh (2010) REDD: A reckoning of environment and development implications, Trends in Ecology & Evolution 25: 396– 402. Global Witness (2007) Cambodia’s family trees. Illegal logging and the stripping of public assets by Cambodia’s elite. Washington, DC: Global Witness Publishing. Goldman, M. (2001) Constructing an environmental state: Eco-governmentality and other transnational practices of a ‘Green’ world bank, Social Problems 48(4): 499– 523. Goldman, M. (2005) Imperial nature. The world bank and struggles for social justice in the age of globalization. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. GRAS A/S (2010) Quality assurance and product verification of the 2010 forest cover assessment in Cambodia. Copenhagen, Denmark: GRAS A/S, University of Copenhagen. December 2010. Hall, D., P. Hirsch and T.M. Li (2011) Powers of exclusion: Land dilemmas in Southeast Asia. Challenges of the agrarian transition in Southeast Asia. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press. Hansen, C.P., J.F. Lund and T. Treue (2009) Neither fast, nor easy: The prospect of Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation (REDD) in Ghana, International Forestry Review 11: 439–455. Hirsch, P.D., W.M. Adams, J.P. Brosius, A. Zia, N. Bariola and J.L. Dammert (2011) Acknowledging conservation trade-offs and embracing complexity, Conservation Biology 25: 259–264. Hoang, L.A., J.-C. Castella and P. Novosad (2006) Social networks and information access: Implications for extension in a rice farming community in Northern Vietnam, Agriculture and Human Values 23: 513–527. Howson, P. and S. Kindon (2015) Analysing access to the local REDD+ benefits of Sungai Lamandau, Central © 2015 Victoria University of Wellington and Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd 125 M. Pasgaard Kalimantan, Indonesia, Asia Pacific Viewpoint 56(1): 96–110. Hughes, C. (2001) Mystics and militants: Democratic reform in Cambodia, International Politics 38(1): 47–64. Hulme, D. (1989) Learning and not learning from experience in rural project planning, Public Administration and Development 9: 1–16. Larson, A.M. and J.C. Ribot (2007) The poverty of forestry policy: Double standards on an uneven playing field, Sustainability Science 2: 189–204. Latour, B. (1986) The powers of association, in J. Law (ed.), Power, action and belief. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. Le Billon, P. (2002) Logging in muddy waters – The politics of forest exploitation in Cambodia, Critical Asian Studies 34: 563–586. Leach, M. and R. Mearns (1996) Challenging received wisdom in Africa, Chapter 1, in M. Leach and R. Mearns (eds.), The lie of the land: Challenging received wisdom on the African environment. Suffolk, UK: James Currey. Lewis, D. and D. Mosse (2006) Theoretical approaches to brokerage and translation, Chapter 1, in D. Lewis and D. Mosse (eds.), Development brokers and translators: The ethnography of aid and agencies. Boulder, CO: Kumarian Press. Li, T.M. (2007) Practices of assemblage and community forest management, Economy and Society 36: 263– 293. Marion Suiseeya, K.R. and S. Caplow (2013) In pursuit of procedural justice: Lessons from an analysis of 56 forest carbon project designs, Global Environmental Change 23(5): 968–979. McCarthy, J., J. Vel and S. Afiff (2012) Trajectories of land acquisition and enclosure: development schemes, virtual land grabs and green acquisitions in Indonesia’s outer islands, Journal of Peasant Studies 39(2): 521– 549. McDermott, M., S. Mahanty and K. Schreckenberg (2013) Examining equity: A multidimensional framework for assessing equity in payments for ecosystem services, Environmental Science & Policy 33: 416–427. Milne, S. and B. Adams (2012) Market masquerades: Uncovering the politics of community-level payments for environmental services in Cambodia, Development and Change 43: 133–158. Mosse, D. (2001) ‘People’s knowledge’, Participation and patronage: Operations and representations in rural development, in B. Cooke and U. Kothari (eds.), Participation. The new tyranny? London: Zed Books. Pact (2010) Report on Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA). Oddar Meanchey community forestry REDD project, Phnom Penh, Cambodia: Pact. Pact (2012) Oddar Meanchey REDD project carbon credits now on the market. Retrieved 25 June 2012, from Website: http://www.pactworld.org/cs/news/ news_archive/carbon_credits_on_the_market Pasgaard, M. (2013) The challenge of assessing social dimensions of avoided deforestation: Examples from Cambodia, Environmental Impact Assessment Review 38: 64–72. 126 Pasgaard, M. and L. Chea (2013) Double inequity? The social dimensions of deforestation and forest protection in local communities in Northern Cambodia, Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies 6(2): 330– 355. Peck, J. and N. Theodore (2010) Mobilizing policy: Models, methods, and mutations, Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 41: 169–174. Peck, J. and N. Theodore (2012) Follow the policy: A distended case approach, Environment and Planning A 44: 21–30. Poffenberger, M. (2009) Cambodia’s forests and climate change: Mitigating drivers of deforestation, Natural Resources Forum 33: 285–296. Rametsteiner, E. (2009) Governance concepts and their application in forest policy initiatives from global to local levels, Small-Scale Forestry 8: 143–158. RECOFTC (2010) Review of community forestry and community fisheries in Cambodia. Phnom Penh, Cambodia: The Center for People and Forests (RECOFTC). RGC (2003) Sub-decree on community forestry management. Pursuant to the approval of the Council of Ministers at its plenary session on 17/10/2003. Unofficial Translation, Edited 30/12/2006. Phnom Penh, Cambodia: Royal Government of Cambodia (RGC). Roeun, V. and P. Vrieze (2011) P Vihear concessions raise fears of disputes. The Cambodia Daily, 12 July 2011. Saito-Jensen, M. and M. Pasgaard (in press) Blocked learning in development aid? Reporting success over failure in Andhra Pradesh, India, Knowledge Management for Development Journal 10. Scott, J. (1990) Domination and the arts of resistance: Hidden transcripts, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Sikor, T., J. Stahl, T. Enters et al. (2010) REDD-plus, forest people’s rights and nested climate governance, Global Environmental Change: Human and Policy Dimensions 20: 423–425. Soenthrith, S. (2011) Villagers complain as land is razed in Oddor Meanchey. The Cambodia Daily, 12 August 2011. Springate-Baginski, O. and E. Wollenberg (2010) REDD, forest governance and rural livelihoods. Bogor, Indonesia: Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR). Sunderlin, W.D., A.M. Larson and P. Cronkleton (2009) Forest tenure rights and REDD+: From inertia to policy solutions, in A. Angelsen (ed.), Realising REDD+: National strategy and policy options. Bogor, Indonesia: Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR). Terra Global (2012) Reduced emissions from degradation and deforestation in community forests – Oddar Meanchey, Cambodia. Project Design Document for validation under Climate, Community & Biodiversity Standard (Version 3-0) July 26, 2012. Developed by Terra Global Capital for The Forestry Administration of the Royal Government of Cambodia. Retrieved 26 March 2014, from Website: https://s3.amazonaws .com/CCBA/Projects/Reducing_Emissions_from _Degradation_and_Deforestation_in_Community _Forests-Oddar_Meanchey%2C_Cambodia/PD_CCB _OMC_07-30-2012.pdf © 2015 Victoria University of Wellington and Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd Lost in translation? Thompson, M.C., M. Baruah and E.C. Carr (2011) Seeing REDD+ as a project of environmental governance, Environmental Science & Policy 14: 100–110. Thul, P.C. (2011, August 9) World Bank stops funds for Cambodia over evictions. Reuters. Retrieved from http://www.reuters.com/assets/print?aid=USL3E7J920 D20110809 Tsing, A.L. (2005) Friction: An ethnography of global connection, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. UN (2009a) About REDD+. Retrieved 26 March 2014, from Website: http://www.un-redd.org/AboutREDD/tabid/ 582/Default.aspx UN (2009b) What are the multiple benefits of REDD+? Retrieved 26 March 2014, from Website: http://www .un-redd.org/AboutUNREDDProgramme/Global Activities/New_Multiple_Benefits/tabid/1016/Default .aspx United Nations REDD Programme (2010) National programme document – Cambodia. UN-REDD Programme 5th Policy Board Meeting, UNREDD/PB5/ 2010/9. Washington, DC: United Nations. United States Agency for International Development (2004) Cambodia: An assessment of forest conflict at the community level. Washington, DC: USAID. World Bank (2011) Forest carbon partnership facility. Introduction. Last update September 2011. Retrieved 6 March 2012, from Website: http://www.forestcarbon partnership.org/fcp/node/12 Zink, E. (2013) Hot science, high water. Assembling nature, society and environmental policy in contemporary Vietnam. Copenhagen, Denmark: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies (NIAS) Press. © 2015 Victoria University of Wellington and Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd 127

© Copyright 2025