Beyond Badges and Couch-to-5K

Designing for Advanced Amateurs: Beyond Badges and Couch-to-5K Pawel Wo´ zniak t2i Interaction Lab Chalmers University of Technology Gothenburg, Sweden pawelw@chalmers.se Kristina Knaving Department of Applied IT University of Gothenburg Gothenburg, Sweden kristina.knaving@ait.gu.se Abstract In this position paper we postulate a shift in designing for sports and physical exertion. Most past efforts in Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) have concentrated on how to persuade users to engage in physical activity in order to change their lifestyle. We are engaged in ethnographic work with runners and those attending fitness classes. Based on our results, we posit that there is a user group that has been neglected — those committed to a training routine (advanced amateurs) are lacking technology support. We describe how we envision a shift from persuasion to reflection in designing for sports and provide directions for the development of future systems. We suggest that future design should concentrate on the less-than-ideal aspects of running and rich qualitative accounts of the running experience. This can be achieved by stimulating reflection and sense making through new ways of visualising running data and facilitating creating narratives. Author Keywords Running, exertion, sports, race, competition Copyright is held by the author/owners). CHI ’15, April 18th - April 23rd, Seoul, South Korea. Workshop on ’Beyond Personal Informatics: Designing for Experiences of Data’. ACM Classification Keywords H.5.m [Information interfaces and presentation (e.g., HCI)]: Miscellaneous. Introduction A growing interest in health has led to many efforts centered on helping people with very little intrinsic motivation for sports to start fitness activities. Since running is low-cost and readily available for most people, it has been one of the more popular entry sports with dozens of commercial applications built to convince people to start a running routine e.g through gamification [6] or peer pressure [1]. In contrast, our research focuses on how technology support for runners can move from persuading to engage in physical activity to helping the users who are already active reflect and make sense of their regular sports efforts. Our idea is influenced by a general trend in HCI of moving away from theory-motivated persuasive interventions towards building infrastructures for reflection [2]. Those who practice running regularly have a variety of needs that require them to monitor and understand their progress. We believe that providing advanced amateurs with the means to reflect on their routines will not only help internalise motivation (our past research shows that this is crucial motivation goal), but also lead to an overall improved quality of life. This is especially relevant when one considers the different geographical locations inhabited by runners and how the yearly cycles affect their training. Furthermore, one cannot forget about race experiences and how perceptions of feeling healthy are altered by organised events. Advanced Amateur Runners When we studied runners these past two years, we have focused on advanced amateur runners 1 , i.e. individuals 1 Many of the motivations mentioned in this paper are based on our extensive ethnographic research of running communities. The results of this work are now in submission. engaged in a regular training routine with an intention of participating in organised races. These running enthusiasts are often perceived by others as very motivated — they train relatively often and it a factor in how they plan their lives. They also participate in longer races and always strive to finish the race in the best time possible. This perception may be why most technology designed for these runners is focused on delivering numbers as-is, i.e. geopositioning and pulse data with fairly basic graphs. When interviewing advanced amateur runners on motivation, it is clear that they are helped by intrinsic motivations (e.g. ”I like running”), but also that extrinsic motivation (e.g. ”I want to beat my personal best” or ”I want to stay healthy”) are important tools that support their everyday training routines. We also used the Sports Motivation Scale [7] questionnaire, and the results support this finding as well. Many of the interviewed runners also mention the need to set a goal for training as a main motivator for signing up to events. While members of this group often report that they have to run to feel good, they also note that it is sometimes very tough to run and that they have lapsed in their training, sometimes for years. Matching personal expectations is hard and individuals are often unsatisfied if they do not comply with their training goals. This, in turn, affects not only the runner, but also their social environment. We wonder how technology can alleviate this and we believe that more sense making with running data can be of help. The runners we interviewed found it difficult to find time in their often very busy lives to go out running. While the image of race preparation promoted by current running phone app companies and sports stores is that of an ideally dressed runner taking a mid-day run, our work revealed that a more relevant image would be that of a tired father squeezing in a 10pm interval training session in the rain after the kids had gone to bed, or scarfing down a quick sandwich in order to run during the lunch hour. Running data is not complete without the context, and this context is also one of the building blocks of creating a personal running narrative. An often cited reason for dissatisfaction is the weather changes throughout the year, especially in countries with moderate climate. Data has shown that many runners skip running during the winter months, either making do with gym sessions or mostly skipping physical workouts altogether. Supporting advanced amateur running also means supporting the training-event cycles throughout the year, where planned training culminates in a race event, both with very different needs and expectations from technology. Our experience is that current technology rarely take different goals and environments into account. Figure 1: Example of the current state of the art for running applications. Simple maps and elevation plots are not enough to stimulate reflection and enable runners to understand more about their training routines. Another reason is the fairly high number of sports related injuries among amateur runners [9]. This was evident in our supporter interviews, where a third of randomly contacted supporters at a race informed us that they wanted to run the race, but were injured, and by interviewed runners talking about how they regretted past injuries. Injured runners often talked about how they planned to start running again, and stressed both the importance of not over-extending as well as the fear that the need to go out running would make them restart their training too early. Unlike elite runners, who rely on trainers and medical specialists, the runners we interviewed rarely found that they were helped in their decision to decide on the best time to start running by health services. Since they are mainly guided by their own knowledge, it is imperative that they have good decision support to counteract their ambitions. By supporting reflection and sensemaking, we hope that runners can learn more about the patterns that lead to injury. Gamifying fitness classes Another advanced amateur group we are currently investigating is those attending regular fitness classes aimed at overall body development. We are engaged with coaches and users participating in a programme where participants complete a number of challenges to complete quests similar to role-playing games. The coaches have decided that the game is only accessible to those with training experience, a minimum period of two months of continuous attendance is required. The game is paper-based — an overview board is available at the training facilities and participants have their own paper player cards. Figure 2 shows the current version of the system. Figure 2: The current version of the fitness class game with user markers depicting the progress of each user. This setting is quite different than working with runners. The challenge for data collection and, consequently, technology support for the activities is enhancing group dynamics and promoting healthy competition. We are now in a process of determining what the qualities of a groups support system should be. Before the programme began, we administered the Sports Motivation Scale questionnaire to all participants and whenever a new user joins the programme, they are required to complete the form. The impact of the system will be measured by using the questionnaire once again after six months. We are now conducting regular semi-structured interviews with the participants to monitor their progress and the impact of the game on their training experience. Initial interview data indicated that while the users have different motivations to attend the classes (e.g. weight loss, support of other sports, the company of others) they all stress group support as the most important factors that keeps them attending the exhausting training routines. When asked about the toughest moments of the training session, they often report thinking of the praise and support of their training friends. We have also observed that placing and moving the markers in the game became an important group activity and users reported the event as a source of motivation. Figure 3 shows the initial marker placement event. A question that remains is how digital systems can be built to support these types of interactions. Reflecting the human values involved in group activities while still presenting the data for analysis in training support technology remains a challenge for interaction design. Figure 3: Users gathered around the overview board for fitness class progress. On this particular occasion, most users are placing their markers for the first time and thus their starting fitness level is determined. Making Sense of Sports Data The key to our proposed approach is an attempt to use all of the data we can possibly gather about running and create interfaces that will enable runners to understand more about their training. Speed, pace, route length and heart rate measurements are now easily accessible. Soon, more sensors, such as advanced gait and foot strike clips will be available. With an abundance of data produced by every run and even more input generated by training plans, we need to build tools that enable runners to immerse themselves in the data and see the story of their running among the data points. We propose using a data-aware design approach [4] where runners are not only enabled to curate how their running data is collected, but also to analyse and process it for a variety of purposes. Moving away from the map-and-elevation-plot model (see Figure 1 for an example) we know see in most running software can potentially be beneficial. For example, if we can couple workout data with knowledge from physiology and medicine, we will be able to design systems that foster reflection and, hopefully, lead to a reduction in injury rates. Figure 4: Some pictures of a cross country race taken with the Narrative Clip. We also see a need for building more sports memories. In our studies, we often found that runners find it find hard to recall details of past running events. Most importantly, it is quite hard to recall and analyse what happened on race day due to the heightened emotions and intensified exertion. Recall of training sessions, while not intense, is often hampered by their routine nature — most of our respondents, for example, mainly ran in the same limited area because of time constraints. Systems that facilitate recall (such as the SenseCam [3]) are known in HCI and we believe we should seek to apply them in a running context. Enhanced memories of running achievements and the hardships that one had to endure can lead to more satisfaction and motivation. Or, maybe, a memory of a past success can suggest a well-deserved day off? An important question is which data that should be gathered and how it should be presented in order to trigger runner’s memories [8]. In a preliminary effort, we used the NarrativeClip2 mounted on a running belt to gather visual material from a cross country race. Figure 4 presents some of the pictures taken. The material allowed telling a richer story of the race as well as supporting recall of particular events. It also enabled those not participating to become more engaged and ask relevant questions. Furthermore, we are also taking snapshots of the fitness class game. The role of HCI We ask ourselves how HCI can help advanced advanced amateurs make sense of data. As interaction designers, we 2 getnarrative.com have a robust apparatus of visual interface design and interactive information visualization at hand. We know how to build effective, usable and fun interfaces given that we have a profound understanding of the users and the design constrained [5]. In the case of sports technology, we need more understanding before we are able to design the next big thing. Not only do we need more ethnographic studies of running, but we also need to engage in other disciplines that have a tradition of studying sports. We will need more knowledge from the domains of sports physiology and sports psychology to design better systems. Understanding the social aspects of running seem to be particularly challenging as one needs to understand the complicated processes of how runner groups are formed and maintained as well as how runners interact with friends and family. We do not need to redo all the ethnographic work that has already been done, but we rather need focus on studying the role technology plays in the lives of runners. Conclusions In this paper we presented our vision of future sports support technology which stimulates reflection and story telling by creative use of the extensive sensing capabilities available for runners. We shared some of the insights from our studies of runners and races to look for directions for future development. We believe that innovative visualisation can help runners reflect about their training process, understand more about their bodies and enjoy the sport more. We illustrated how a game-based is now used to organise fitness classes and motivate users to improve their physical skills. We also think that there is an emerging need for technology that supports and triggers runner memories as the unique mental state of participating in a race often makes it hard to recall events. Life logging technology can be used to cater to those needs. We also highlighted how HCI needs to enter a dialogue with other disciplines concerned with running to acquire a better understanding of the design constraints involved. [4] We believe that the increased availability of sensor and camera data present a huge opportunity for enabling people to recall, reflect and learn from their activities, and that we have to create solutions that facilitate this process in the future. While we focus on advanced amateur runners, it is likely that increasing storytelling support with the gathered data can translate well to other usage scenarios e.g. helping patients see the progress of their physiotherapy sessions or aiding users who monitor their food intake for health reasons. As there are many opportunities in this area, we hope that future design can be inspired by our analysis. [5] [6] [7] References [1] Arteaga, S. M., Kudeki, M., Woodworth, A., and Kurniawan, S. Mobile system to motivate teenagers’ physical activity. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Interaction Design and Children, IDC ’10, ACM (New York, NY, USA, 2010), 1–10. [2] Brynjarsdottir, H., H˚ akansson, M., Pierce, J., Baumer, E., DiSalvo, C., and Sengers, P. Sustainably unpersuaded: How persuasion narrows our vision of sustainability. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI ’12, ACM (New York, NY, USA, 2012), 947–956. [3] Caprani, N., O’Connor, N. E., and Gurrin, C. Experiencing sensecam: A case study interview [8] [9] exploring seven years living with a wearable camera. In Proceedings of the 4th International SenseCam & Pervasive Imaging Conference, SenseCam ’13, ACM (New York, NY, USA, 2013), 52–59. Churchill, E. F. From data divination to data-aware design. interactions 19, 5 (Sept. 2012), 10–13. Harper, R., Rodden, T., Rogers, Y., and Sellen, A. Being human: Human-computer interaction in the year 2020. Microsoft Research, 2008. Kan, A., Gibbs, M., and Ploderer, B. Being chased by zombies!: Understanding the experience of mixed reality quests. In Proceedings of the 25th Australian Computer-Human Interaction Conference: Augmentation, Application, Innovation, Collaboration, OzCHI ’13, ACM (New York, NY, USA, 2013), 207–216. Pelletier, L. G., Fortier, M. S., Vallerand, R. J., Tuson, K. M., Briere, N. M., and Blais, M. R. Toward a new measure of intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, and amotivation in sports: The sport motivation scale (sms). Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 17 (1995), 35–35. Sellen, A. J., and Whittaker, S. Beyond total capture: A constructive critique of lifelogging. Commun. ACM 53, 5 (May 2010), 70–77. van Gent, B. R., Siem, D. D., van Middelkoop, M., van Os, T. A., Bierma-Zeinstra, S. S., and Koes, B. B. Incidence and determinants of lower extremity running injuries in long distance runners: a systematic review. British Journal of Sports Medicine 41, 8 (2007), 469–480.

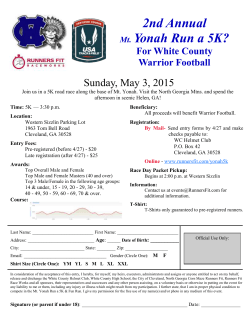

© Copyright 2025