The Use of Iron Sucrose Complex for Christian Breymann

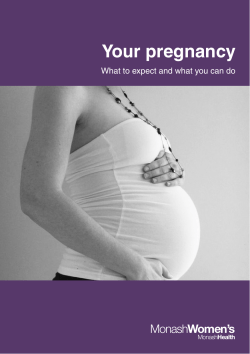

The Use of Iron Sucrose Complex for Anemia in Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period Christian Breymann Iron-deficiency anemia resulting in reduced blood reserves is one the most common problems in pregnancy. It is estimated that 20% to 50% of the world population is suffering from iron deficiency and iron-deficient states, pregnancy being one of the most important “risk factors” for iron deficiency and iron-deficiency anemia. The traditional treatments, ie, oral iron therapy and blood transfusion, involve significant drawbacks. High doses of oral iron frequently cause side effects, and noncompliance is common. Therefore, intravenous iron, alone or in association with recombinant human erythropoietin (rHuEPO) therapy, has been considered as an alternative in the management of iron deficiency in this setting. There is increasing evidence that iron sucrose is safe for the mother and the fetus using the recommended dosages and therapy regimens. Iron sucrose is effective in pregnant and postpartum patients who do not respond to oral iron, who are noncompliant to oral iron, or who are treated with rHuEPO. In both cases, according to the present data, the expected hemoglobin increase and time for therapy are predictable in responding patients. Whether it is reasonable to wait for a response to oral iron in moderate to severe anemia is therefore questionable. Indications for the use of iron sucrose complex are: preexisting (moderate– severe) anemia; no effect of oral iron; side effects of oral iron; refusal of blood transfusion (eg, Jehovah’s Witness patients); limited time until delivery; coexisting risks (eg, bowel disease, renal disease); pre- and postoperative period and postpartum anemia. Future fields of research are the evaluation of patient satisfaction and quality of life, impact on costs and hospital stay, impact on blood transfusion frequency and mortality rate, and finally impact on other factors such as breast feeding behavior and neonatal outcome such as birth weight, prematurity and neonatal iron stores. Semin Hematol 43(suppl 6):S28-S31 © 2006 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. I ron-deficiency anemia is one the most common problems in pregnancy. It is estimated that 20% to 50% of the world population is suffering from iron deficiency and iron-deficient states, pregnancy being one of the most important “risk factors” for iron deficiency and iron-deficiency anemia.1-3 According to World Health Organization (WHO) data presented at the Federation International d’Obstetrique e Gynecology (FIGO) meeting in 2003 in Chile, around 500,000 maternal death cases per year and 20,000,000 morbidity cases per year are related to iron deficiency and anemia. In view of the fetal and maternal risks associated with irondeficiency anemia, it is obvious that treating anemia efficiently would lead to a considerable reduction in the risk factors affecting pregnancy and fetal outcome (Table 1). Feto Maternal Medicine, Obstetric Research, Feto Maternal Hematology Research Group, University Hospital Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland. Address correspondence to Christian Breymann, MD, University Hospital Zurich, Frauenklinikstr. 10, 8091 Zurich, Switzerland. E-mail: christian. breymann@usz.ch S28 0037-1963/06/$-see front matter © 2006 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. doi:10.1053/j.seminhematol.2006.08.002 The traditional treatments, ie, oral iron therapy and blood transfusion, involve significant drawbacks. High doses of oral iron frequently cause side effects, and noncompliance is common. In addition, such therapy has to be given for a long time in cases of severe iron deficiency, and absorption and red blood cell production are influenced by additional pathologies such as renal disease or chronic inflammatory bowel disease in pregnancy. As far as blood transfusions are concerned, because of the risk of infection (bacterial, viral, prions) and immunomodulation associated with allogeneic blood products, especially in this young and otherwise healthy population, transfusions are used only in the most severe cases and particularly in life-threatening situations.4-6 Therefore, intravenous iron, alone or in association with recombinant human erythropoietin (rHuEPO), has been considered as an alternative in the management of iron deficiency in this setting.7-15 Since the early 1990s, iron sucrose (Venofer®, Vifor, St. Gallen, Switzerland) has been the only parenteral iron preparation used during pregnancy and the puerperium at the Zurich University Hospital Obstetrics Clinic. Intravenous iron sucrose in obstetric anemia S29 Table 1 Fetal and Maternal Risks as a Consequence of Anemia Fetus Mother Growth retardation Prematurity Quality of life Anemia symptoms (dizziness, cardiovascular, etc) Death in utero Lactation habits (insufficient milk syndrome) Amnion rupture Physical performance Infection “Baby blues” Fetal programming Infection rate (feto-placental miss-ratio) Wound healing, fever Prolonged hospital stay Data on the safety of the iron sucrose complex were first collected in a multicenter study in 1998. The side effect rate following the administration of 2000 ampoules, with a maximum single dose of 200 mg intravenously, was found to be less than 0.5%.16 Our data are in accordance with previously published studies showing that iron sucrose complex produces no side effects during pregnancy. In accordance with Obstetrics Clinic guidelines, an incremental treatment plan is used in anemia management.4 Prerequisites for the use of parenteral iron include diagnostic investigations and fulfillment of the following inclusion criteria: ● Hemoglobin (Hb) ⬍10 g/dL ● No effect of oral iron therapy (160 –200 mg/d) over 2 weeks (ie, no Hb increase and/or reticulocyte response) ● Proven iron deficiency (serum ferritin ⬍15 g/L) ● Exclusion of hemoglobinopathy or other red cell disorders ● Exclusion of acute inflammatory state (C-reactive protein determination) ● Gestational age over 16 weeks The first Hb determination is normally carried out during the first trimester, with oral iron prescribed in the first instance only if the Hb value is less than 10 g/dL. If the Hb level on oral iron treatment falls below 10 g/dL within 2 to 4 weeks, or if the Hb level on the first diagnostic test is already less than 10 g/dL, we use the iron sucrose complex as the treatment of first choice. Practical Use of Iron Sucrose at the Zurich Clinic of Obstetrics The substance is administered through a venous butterfly canula, once correct positioning in the vein has been tested with NaCl. Iron sucrose can be administered undiluted as a bolus or diluted, eg, to 100 to 200 mL of isotonic NaCl solution as a short infusion. Administration of a test dose (1 mL) is required in different countries. The bolus injection may be given over 5 to 10 minutes; however, a short infusion over approximately 20 minutes is considered safer. The maximum single dose is 200 mg. We generally give two doses a week to achieve a target Hb value of 11 g/dL. The treatment can be given on an outpatient basis without any problems; in our experience, a long period of monitoring is not usually necessary following administration. Anemia of Pregnancy Between 1992 and 2005, more than 500 pregnant women with anemia were treated at the Zurich Obstetrics Clinic. The mean treatment duration was 25 (8 to 29) days, with a mean total dose of 1,000 mg (400 to 1,600 mg) iron sucrose, corresponding to five doses of 200 mg. There are several studies on, and clinical experience with, the use of iron sucrose during pregnancy and in the postpartum period. Overall, a high level of efficacy and safety was demonstrated in all studies. Similarly, parenteral iron therapy with the iron sucrose complex was superior to oral iron in all studies so far. Concerning evidence of effectiveness of iron sucrose in pregnancy, it can be concluded that iron sucrose is effective: ● in patients not responding to oral iron ● in combination with rHuEPO, particularly in the case of a significant inflammatory state ● in severe anemia (Hb ⬍9 g/dL) Baseline hematologic values and results of intravenous iron sucrose therapy of pregnant anemic women are given in Table 2. The study of Bayoumeu et al showed no advantage of iron sucrose over oral iron with regard to Hb increase but an advantage concerning ferritin levels at the end of treatment.7 In the Cochrane Database Review (2001) of 54 studies on the use of intravenous iron during pregnancy, only one study showed a favorable Hb response at 36 weeks and pre-delivery, using intravenous iron compared to oral iron in anemic women.17 It should be noted that this review includes only studies with other intravenous iron preparations such as iron dextran and ferric gluconate, while most positive experiences with iron sucrose complex in pregnancy were published from 2000 onwards. These studies should be included in a forthcoming new edition of this review. Table 2 Baseline Hematologic Values and Values After Therapy of Pregnant Anemic Women With Iron Sucrose Complex (200 mg IV twice weekly) Hb (g/dL) Reticulocytes (%) MCV (fL) MCH (pg) Transferrin saturation (%) Ferritin (g/L) Baseline End (day 25) 9.1 2.2 79 25 6 6 11.0* 4.2* 87* 28* 20* 180* Abbreviations: IV, intravenous; Hb, hemoglobin; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; MCH, mean corpuscular volume. Data from Huch and Breymann.4 *P <.01 v baseline values. C. Breymann S30 Postpartum Anemia The treatment of postpartum anemia depends on the severity of the anemia and/or additional maternal risk factors or comorbidities. A young, healthy woman can compensate for heavy blood losses far better than a puerpera with a heart defect who may decompensate even after less severe losses. In addition, blood losses need to be viewed in relation to the body mass and the estimated total blood volume. Another consideration is that significant errors can be made particularly when estimating blood loss. Blood loss is often underestimated, which can readily be verified by comparing prepartum and postpartum Hb levels. In addition to volume replacement, treatment options include the administration of oral iron, parenteral iron and allogeneic blood transfusion. Another option to be considered is the administration of rHuEPO.4,11,18-23 Oral iron should be prescribed at hemoglobin levels of over 9.5 g/dL; 80 to 100 mg/d is sufficient in such cases. The iron supplementation should be continued for a period of several months, so as to normalize not only the Hb but also the iron stores. In one study, we were able to show that puerperae with iron deficiency, but no anemia can replenish their iron stores through iron supplementation only.24 Thus, puerperae who have iron deficiency and anemia are particularly likely to have high iron requirements. We therefore continue to give iron for at least 6 months. In most cases, giving oral iron is not enough when treating severe anemia, since the endogenous iron stores are usually depleted and not enough iron is provided to ensure sufficient erythropoiesis. As mentioned earlier, the reasons for this include limited absorption, poor compliance at high doses due to adverse effects, and low plasma transferrin saturation levels, which lead to functional iron deficiency. In addition, an inflammatory reaction can occur, particularly following surgically assisted deliveries and cesarean section, leading to iron sequestration in the macrophages and decrease of intestinal absorption, so that the administered iron is not available for hemopoiesis.10,18 One alternative is the parenteral administration of iron sucrose. The high plasma iron concentrations that occur shortly after intravenous administration bypass the limited release of iron from the reticuloendothelial system and the inhibited absorption through the intestinal mucosa, thus delivering sufficient quantities of iron for erythropoiesis. As in pregnancy, we follow an incremental treatment plan using parenteral iron sucrose at Hb levels below 9.5 g/dL.4 Since 1996 we have published several studies on the use of iron sucrose (with or without rHuEPO) for postpartum anemia in various dosages between 100 and 800 mg (total dose). Depending on the selected total dose, Hb increases between 2.1 and 3.5 g/dL were observed after 14 days (Fig 1).4,19,20,22,23 In our studies, a reduction of transfusion frequency was not detected since transfusion was not an outcome parameter, ie, we would consider transfusion only in emergency cases and not as a regular treatment option. Gravier et al showed a Hb increase of 3.8 g/dL after 14 days (400 to 600 mg total dose) and a time difference of 14 days versus 30 days (with oral iron) until target Hb was reached.11 Delta-Hb 3.5 3 2.5 2 (g/dL) Day 14 1.5 1 0.5 0 100 mg 400 mg 800 mg Iron Sucrose total dose FERRITIN 200 180 160 140 120 (mg/dL) 100 80 60 40 20 0 Baseline Day 14 100 mg 400 mg 800 mg Iron Sucrose Total Dose Figure 1 Hemoglobin increase (delta Hb from baseline) and ferritin (absolute increase) 14 days after therapy with iron sucrose complex in various total dosages in women with postpartum anemia.18-20 More recently, Broche et al retrospectively analyzed data from 4,292 patients who gave birth in their institution between April 2001 and March 2003. All patients who presented with postpartum anemia (Hb ⬍8 g/dL) within 48 hours of delivery (n ⫽ 217, ie, 5% of all parturients), were included in the study. Two groups were distinguished based on the availability of intravenous iron sucrose in the institution at the time of delivery. The analysis comprised clinical and laboratory outcomes. Between April 2001 and March 2002, 103 patients received either blood transfusions (n ⫽ 15 [14.6%]) or oral iron (n ⫽ 88), whereas between April 2002 and March 2003, 114 patients received either blood transfusion (n ⫽ 5 [4.4%]), oral iron (n ⫽ 66), or intravenous iron sucrose (n ⫽ 43). The mean total dose of intravenous iron administered was 359 mg (range, 200 to 600 mg). The mean increase in Hb concentration over 7 days in patients who received iron sucrose was significantly higher compared to those who received oral iron exclusively (1.86 ⫾ 0.91 [0 to 3.8] v 0.87 ⫾ 0.65 [⫺0.4 to 1.8] g/dL; P ⫽ 3.9 ⫻ 10⫺8). The authors concluded that since the availability of intravenous iron sucrose in their institution, the number of transfused patients had been divided by three; the increase in Hb concentrations was significantly higher with iron sucrose than with oral iron in patients with postpartum anemia. Iron sucrose was well tolerated.25 In summary, iron sucrose improves postpartum anemia in a dose-dependent manner with a maximum increase for an 800-mg total dose. Iron status is improved in all patients; Intravenous iron sucrose in obstetric anemia however, a lasting (depot) effect over several weeks has not been shown. Blood transfusion frequency was reduced in one study.25 Two studies showed that iron sucrose is superior to oral iron already at day 7, again depending on the dosage.11 In contrast, a recent study by Dede et al showed no difference between iron sucrose and oral iron until 28 days after delivery with regard to hematological parameters, although the effect on iron status was greater with iron sucrose.26 The Cochrane Collaboration reports on several trials comparing different iron compounds (with or without rHuEPO) for the treatment of postpartum anemia. The authors conclude that a favorable outcome was seen in patients who were additionally treated with rHuEPO, and that further trials, focusing on iron administration, the role of dietary iron and blood transfusion, are needed.27 Conclusion With regard to the use of intravenous iron in obstetrics, there is increasing evidence that iron sucrose is safe for the mother and the fetus using the recommended dosages and therapy regimens. Iron sucrose is effective in pregnancy and in the postpartum period in patients who do not respond to oral iron, who are non-compliant to oral iron, or who are treated with rHuEPO (rHuEPO is not currently registered for use in pregnancy and postpartum). In both cases, according to the present data, the expected hemoglobin increase and time for therapy are predictable in responding patients. Whether it is reasonable to wait for a response to oral iron in moderate to severe anemia is therefore questionable. Indications for the use of iron sucrose complex are: preexisting (moderate–severe) anemia; no effect of oral iron; side effects of oral iron; refusal of blood transfusion (eg, Jehovah’s Witness patients); limited time until delivery; coexisting risks (eg, bowel disease, renal disease); and pre- and postoperative period and postpartum anemia. According to our experience, the effectiveness of iron sucrose is increased by the use of rHuEPO in patients with a profound postpartum inflammatory state such as anemic patients after cesarean section.19 Future fields of research are the evaluation of patient satisfaction and quality of life, impact on costs and hospital stay, impact on blood transfusion frequency and mortality rate, and finally impact on other factors such as breast feeding behavior and neonatal outcome such as birth weight, prematurity and neonatal iron stores. References 1. Allen LH: Pregnancy and iron deficiency: unresolved issues. Nutr Rev 55:91-101, 1997 2. Hercberg S, Galan P, Preziosi P: Consequences of iron deficiency in pregnant women: Current issues. Clin Drug Invest 19:1-7, 2000 (suppl 1) 3. Hercberg S, Preziosi P, Galan P: Iron deficiency in Europe. Public Health Nutr 4:537-545, 2001 4. Huch R, Breymann C: Anaemia in Pregnancy and Postpartum (ed 1). Bremen, Germany, Uni-Med Verlag, 2005 5. Milman N, Agger AO, Nielson OJ: Iron supplementation during pregnancy. Effect on iron status markers, serum erythropoietin and human placental lactogen. A placebo controlled study in 207 Danish women. Dan Med Bull 38:471-476, 1991 S31 6. Williamson L, Lowe S, Love E, Cohen H, Soldan K, McClelland DB, et al: Serious hazards of transfusion (SHOT) initiative: Analysis of the first two annual reports. BMJ 319:16-19, 1999 7. Bayoumeu F, Subiran-Buisset C, Baka NE, Legagneur H, MonnierBarbarino P, Laxenaire MC: Iron therapy in iron deficiency anemia in pregnancy: Intravenous route versus oral route. Am J Obstet Gynecol 186:518-522, 2002 8. Breymann C, Major A, Richter C, Huch R, Huch A: Recombinant human erythropoietin and parenteral iron in the treatment of pregnancy anemia: A pilot study. J Perinat Med 23:89-98, 1995 9. Breymann C, Visca E, Huch R, Huch A: Efficacy and safety of intravenously administered iron sucrose with and without adjuvant recombinant human erythropoietin for the treatment of resistant iron-deficiency anemia during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 184:662-667, 2000 10. Crichton R, Danielson B, Geisser P: Iron Therapy. Bremen, Germany, Uni-Med Verlag, 2005 11. Gravier A, Descargues G, Marpeau L: Comment éviter les transfusions dans le post-partum: intérêt d’une supplémentation martiale par voie intraveineuse. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) 28:77-78, 1999 12. Koenig HM, Levine EA, Resnick DJ, Meyer WJ: Use of recombinant human erythropoietin in a Jehovah’s Witness. J Clin Anesth 5:244-247, 1993 13. Krafft A, Breymann C, Huch R, Huch A: Intravenous iron sucrose in two pregnant women with inflammatory bowel disease and severe iron deficiency anemia. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 79:720-722, 2000 14. al-Momen AK, al-Meshari A, al-Nuaim L, Saddique A, Abotalib Z, Khashogji T, et al: Intravenous iron sucrose complex in the treatment of iron deficiency anemia during pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 69:121-124, 1996 15. Polatti F, Mandelli B: Treatment with intravenous iron of hypochromic anemia in pregnancy. Boll Soc Medico Chir Pavia 97:13-16, 1983 16. Hoigné R, Breymann C, Künzi U, Brunner F: Parenteral iron therapy: problems and possible solutions. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 128:528535, 1998 17. Cuervo L, Mahomed K: Treatments for iron deficiency anaemia in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2):CD003094, 2001 18. Breymann C: Modern therapy concepts for severe anaemia in pregnancy and post partum. In: Huch A, Huch R, Breymann C (eds): Prevention and Management of Anaemia in Pregnancy and Postpartum Haemorrhage. Zurich, Switzerland, Schellenberg Druck AG, 1998, pp 107-122 19. Breymann C, Richter C, Hüttner C, Huch R, Huch A: Effectiveness of recombinant erythropoietin and iron sucrose vs. iron therapy only, in patients with postpartum anaemia and blunted erythropoiesis. Eur J Clin Invest 30:154-161, 2000 20. Breymann C, Zimmermann R, Huch R, Huch A: Use of recombinant human erythropoietin in combination with parenteral iron in the treatment of postpartum anaemia. Eur J Clin Invest 23:123-126, 1996 21. Treatment of iron deficiency anemia in pregnancy and the immediate puerperium and other ferropenic conditions with saccharated iron administered intravenously in fractionated doses. XIVth International Congress of Haematology, Sao Paolo, Brazil, 1972 22. Zimmermann R, Breymann C, Huch R, Huch A: rHuEPO in the treatment of postpartum anemia: Subcutaneous versus intravenous administration. Clin Investig 72:S25-S30, 1994 (suppl) 23. Zimmermann R, Breymann C, Richter C, Huch R, Huch A: rhEPO treatment of postpartum anemia. J Perinat Med 23:111-116, 1995 24. Krafft A, Perewusnyk G, Hänseler E, Quack K, Huch R, Breymann C: Effect of postpartum iron supplementation on red cell and iron parameters in non-anaemic iron-deficient women: A randomised placebocontrolled study. BJOG 112:445-450, 2005 25. Broche DE, Gay C, Armand-Branger S, Grangeasse L, Terzibachian JJ: Anémies sévères du post-partum immédiat. Pratique clinique et intérêt du fer par voie intraveineuse. Gynecol Obstet Fertil 32:613-619, 2004 26. Dede A, Uygur D, Yilmaz B, Mungan T, Ugur M: Intravenous iron sucrose complex vs. oral ferrous sulfate for postpartum iron deficiency anemia. Int J Gynecol Obstet 90:238-239, 2005 27. Dodd J, Dare MR, Middleton P: Treatment for women with postpartum iron deficiency anaemia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4):CD004222, 2004

© Copyright 2025