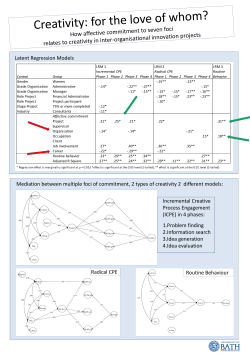

modelling of the creative economy sustainable development