Caffeine During Pregnancy and Lactation Shanae Teuscher Weber State University

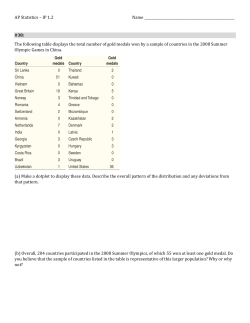

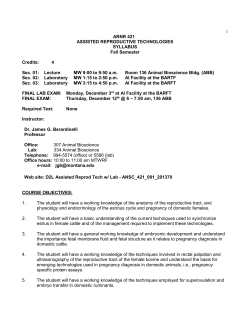

Caffeine During Pregnancy and Lactation Shanae Teuscher Weber State University Knowing and understanding the effects caffeine can and may have on the human body is important, but especially for women during times of pregnancy and lactation. Gaining an understanding of its possible effects on a mother and her baby will allow each woman to knowledgeably weigh out the potential risks and benefits, and then to choose for herself what she’d like to submit her body and baby to. Caffeine is a stimulant that is naturally produced in the leaves and seeds of many plants and it is also artificially produced and added to some foods (Black & Gavin, 2008). The following table shows several of the common beverages, foods, and supplements and the amount of caffeine that each contains: Drink/Food/Supplement SoBe No Fear Monster energy drink Rockstar energy drink Red Bull energy drink Jolt cola Mountain Dew Coca-Cola Diet Coke Pepsi 7-Up Brewed coffee (drip method) Iced tea Cocoa beverage Chocolate milk beverage Dark chocolate Milk chocolate Jolt gum Cold relief medication Vivarin Excedrin extra strength Source: Article by Black & Gavin, 2008 Amount of Drink/Food 8 ounces 16 ounces 8 ounces 8.3 ounces 12 ounces 12 ounces 12 ounces 12 ounces 12 ounces 12 ounces 5 ounces 12 ounces 5 ounces 8 ounces 1 ounce 1 ounce 1 stick 1 tablet 1 tablet 2 tablets *denotes average amount of caffeine Amount of Caffeine 83 mg 160 mg 80 mg 80 mg 72 mg 55 mg 34 mg 45 mg 38 mg 0 mg 115 mg* 70 mg* 4 mg* 5 mg* 20 mg* 6 mg* 33 mg 30 mg* 200 mg 130 mg As is indicated, many of the medicines used for pain relief, headaches, migraines, colds, and deferring sleep contain caffeine. Although caffeine is widely used and accepted, it is defined as a drug because of its effect on the nervous system (Black & Gavin, 2008). Generally, an intake of caffeine increases concentration and puts off feelings of tiredness for a period time (Mahan & Escott-Stump, 2008, p. 1277). Caffeine intake may also lead to unpleasant long-term effects such as increased body temperature, restlessness, nervousness, increased urination, insomnia, flushed face, stomach upsets, and muscle twitching (National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre [NDARC], 2005). American culture, combined with caffeine’s wide availability, easy access, placement in commonly consumed beverages and foods, and its possibility of addiction, allows and encourages millions of Americans to consume it on a regular basis. On average, an American adult consumes around 200 mg of caffeine a day (NDARC, 2005 and Mahan & Escott-Stump, 2008, p. 1277) and the average woman takes in over 30 gallons of caffeinated drinks a year (Somer, 2001). Although caffeine is widely accepted as a common ingredient in American’s everyday diets, one may want to take caution and explore its possible effects in the diet of mothers and infants, especially during times of pregnancy and lactation. Depending on the amount and form of caffeine consumed, health conditions, the size of ones body, and ones sensitivity to it, caffeine affects individual’s bodies differently and in varying time frames. Extensive research has shown that throughout pregnancy, women and infants consuming caffeine may be affected in a variety of ways. The likelihood of getting pregnant, fetal mortality rates and birth weight can all be affected by maternal caffeine ingestion. Breastfeeding infants may also be affected by caffeine absorbed into the breast milk. Studies give contradictory reports on the association between amounts of consumed caffeine and infertility in women. According to the March of Dimes, consuming small amounts of caffeine probably won’t reduce women’s chances of becoming pregnant; however, some studies have found that women who consume more than 300 mg of caffeine a day may have trouble conceiving (as cited by the Reproductive Toxicology Center, 2007). But upon the close of a clinical study done on 104 women who were trying to conceive, it was concluded that women who consumed more than 100 mg of caffeine (200 mg less then the previously sighted article) were half as likely to get pregnant as those who consumed little to no caffeine in their diets (Wilcox et al., 2008). However, there are also numerous studies concluding that caffeine doesn’t actually affect conception, one of which states that caffeine alone won’t affect the probability of conception (Hakim, Gray, & Zacur, 1998). Given these conflicting reports, if a woman is trying to conceive and isn’t successful, she may consider cutting back on the amount of caffeine she regularly consumes. The effect of caffeine on pregnancy has been thoroughly researched. During pregnancy, maternal consumption of caffeine, and everything else, reaches the fetus by crossing the placenta. Maternally ingested caffeine may influence cell development and decrease blood flow to the placenta, which can harm the baby, however, if the arteries are constricted, the amount of blood flow may be dramatically limited which can result in miscarriage (Weng, Odouli, & Li, 2008). The half life and elimination time of caffeine in the body both greatly increase compared to that of a woman who isn’t expecting a baby (Berger, 2008). Studies completed on caffeine’s affects on the fetus also vary but should all be taken seriously. One study, found in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, concludes that compared to women who don’t consume caffeine, women who consume it, in amounts equal to, or in excess of 200 mg a day, are twice as likely to miscarry (Weng et al., 2008). In a different study found in the American Journal of Epidemiology, over a period of 6 years, from 1996 to 2002, over 80,000 women were questioned about their coffee consumption during pregnancy. Their pregnancy information and medical records were also reviewed. Of those women being studied, it was discovered that over 1,000 of them miscarried. Upon the conclusion of the study, the authors found that the elevated levels of coffee consumption during pregnancy were linked with a higher risk of fetal death (Bech, Nohr, Vaeth, Henriksen, & Olsen, 2005). For years experts have wondered if consuming caffeine and low infant birth weight were related. Several studies have been conducted, but with differing results. Some say that smaller amounts of caffeine regularly consumed may affect birth weight, while others conclude that caffeine isn’t a factor in birth weight at all. Recent research conducted regarding the association of birth weight and caffeine in the maternal diet concludes that unless caffeine is consumed in amounts greater than 600 mg on a daily basis it probably isn’t linked to a light birth weight (Bracken, Triche, Belanger, Hellenbrand, & Leaderer, 2002). Research involving after-birth defects in infants and children whose mothers consumed caffeine show that the effects aren’t long-term. The Center for Addiction and Mental Health [CAMH] affirms that newborns of women who consume large amounts of caffeine (more than 500 mg/day) while pregnant may be more likely to have cardiac arrhythmias: faster or irregular heart rates, tachypnea: faster breathing, and may sleep less than normal in the first days of life (as cited in Hadeed & Siegel, 1993, p. 45-47). The CAMH also states that there aren’t reports of exposure to caffeine having lasting or life-long effects on children (CAMH, 2007). During lactation, consumption of caffeine results in it being excreted into the breast milk. The amount of actual caffeine released in the milk and that the baby consumes is generally minor and usually will not show significant effects. However, if an infant becomes fussy, irritable, or has difficulty sleeping the American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP] Committee on Drugs recommends moderating or discontinuing caffeine intake (AAP, 2001). While there aren’t any regulatory or definitive guidelines for caffeine amounts during pregnancy and lactation, and while effects may vary, it is wise to take these and other sources and studies into consideration when determining dietary intake. Limiting or discontinuing caffeine intake during pregnancy and lactation seems to be a wise step in creating a healthy environment and diet for both mother and child. When in doubt, one should ask their health care provider for advice. REFERENCES American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Drugs. Policy Statement: The Transfer of Drugs and Other Chemicals into Human Milk. Pediatrics, September 2001, volume 108, number 3, pages 776-789. Bech B.H., Nohr E.A., Vaeth M., Henriksen T.B., Olsen J. (2005) Coffee and fetal death: a cohort study with prospective data. American Journal of Epidemiology 162:983–990. Berger A: Effects of caffeine consumption during pregnancy. J Reprod Med 33:945-56, 1988. Retrieved May 24, 2008, from http://thomsonhc.com Black, J.D., Gavin, M.L. (2008). Caffeine. Retrieved May 23, 2008, from http://www.kidshealth.org Bracken M.B., Triche E.W., Belanger K., Hellenbrand K., Leaderer B.P., (2003) Association of maternal caffeine consumption with decrements in fetal growth. American Journal of Epidemiology 157:456-466 Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. (2007). Caffeine. Retrieved May 24, 2008, from http://www.camh.net Hadeed, A. & Siegel, S. (1993). Newborn cardiac arrhythmias associated with maternal caffeine use during pregnancy. Clinical Pediatrics, 32 (1), 45–47. Hakim R.B., Gray R.H., & Zacur H.: Alcohol and caffeine consumption and decreased fertility. Fertil Steril 1998; 70:632-637. Mahan, L.K. & Escott-Stump, S. (2004). Appendix 39: Nutritional Facts on Caffeine-Containing Products. Krause’s Food, Nutrition, and Diet Therapy (12 ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. March of Dimes. (Feb. 2008) Caffeine in pregnancy. Retrieved May 23, 2008, from http://www.marchofdimes.com National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre of the University of New South Wales. (2005) NDARC fact sheet [caffeine]. Retrieved May 23, 2008, from http://ndarc.med.unsw.edu.au Pollard I., Murray J.F., Hiller R., Scaramuzzi R.J., Wilson C.A.: Effects of Preconceptual Caffeine Exposure on Pregnancy and Progeny Viability. J Matern Fetal Med 1999; 8:220-4. Reproductive Toxicology Center. Caffeine. Updated 8/1/07, accessed by the March of Dimes 1/22/08. Somer, E. (October, 29, 2001) Jittery about caffeine during pregnancy. Is caffeine okay during pregnancy?. Retrieved May 23, 2008, from http://www.webmd.com Stanton C.K. & Gray R.H.: Effects of caffeine consumption on delayed conception. American Journal of Epidemiology 1995; 142:1322-1329. Weng, X., et al. Maternal Caffeine Consumption during Pregnancy and the Risk of Miscarriage: A Prospective Cohort Study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, published online, January 21, 2008. Wilcox A. et al: Caffeinated beverages and decreased fertility. Lancet 2:1453-6, 1988. Retrieved May 24, 2008, from http://www.thompsonhc.com NUTRITION SOURCE RATINGS Name of reference Author/ Credentials Source Purpose References Total Points AAP Bech, B.H. et al. Berger, A. Black, J.D. et al. Bracken, M.B. et al. CAMH Hadeed, A. et al. Hakim, et al. Mahan, L.K. et al. March of Dimes NDARC Pollard, I. et al. Reproductive Toxicology Center 0 2 2 2 2 0 1 2 2 0 0 2 0 2 2 2 1 2 1 2 2 2 1 1 2 2 2 2 2 1 2 1 2 2 2 1 2 2 1 2 2 2 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 0 2 2 6 8 8 5 8 4 7 8 8 4 3 8 5 Somer, E. Stanton, C.K. et al. Weng, X. et al. Wilcox, A. et al. 2 2 2 2 1 2 2 2 1 2 2 2 0 2 2 2 4 8 8 8

© Copyright 2025