B3 (14) SELF-INDUCED VOMITING AND DENTAL EROSION â A

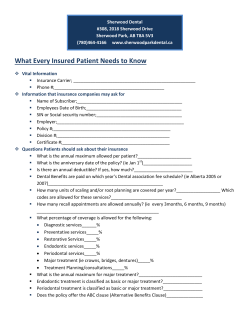

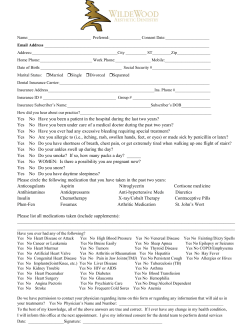

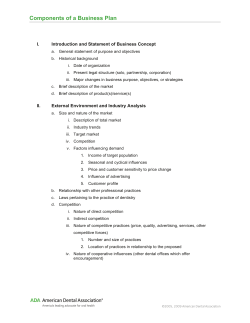

B3 (14) SELF-INDUCED VOMITING AND DENTAL EROSION – A CLINICAL STUDY & ASSOCIATION BETWEEN HARMFUL ALCOHOL USE AND PERIODONTAL STATUS ACCORDING TO GENDER AND SMOKING & EARLY CHILDHOOD CARIES AND ITS RELATIONSHIP WITH PERINATAL, SOCIOECONOMIC AND NUTRITIONAL RISKS Approved for 2 Continuing Educational Units. Uhlen et al. BMC Oral Health 2014, 14:92 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6831/14/92 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Self-induced vomiting and dental erosion – a clinical study Marte-Mari Uhlen*, Anne Bjørg Tveit, Kjersti Refsholt Stenhagen and Aida Mulic Abstract Background: In individuals suffering from eating disorders (ED) characterized by vomiting (e.g. bulimia nervosa), the gastric juice regularly reaches the oral cavity, causing a possible risk of dental erosion. This study aimed to assess the occurrence, distribution and severity of dental erosions in a group of Norwegian patients experiencing self-induced vomiting (SIV). Methods: The individuals included in the study were all undergoing treatment at clinics for eating disorders and were referred to a university dental clinic for examinations. One calibrated clinician registered erosions using the Visual Erosion Dental Examination (VEDE) system. Results: Of 72 referred patients, 66 (63 females and three males, mean age 27.7 years) were or had been experiencing SIV (mean duration 10.6 years; range: 3 – 32 years), and were therefore included in the study. Dental erosions were found in 46 individuals (69.7%), 19 had enamel lesions only, while 27 had both enamel and dentine lesions. Ten or more teeth were affected in 26.1% of those with erosions, and 9% had ≥10 teeth with dentine lesions. Of the erosions, 41.6% were found on palatal/lingual surfaces, 36.6% on occlusal surfaces and 21.8% on buccal surfaces. Dentine lesions were most often found on lower first molars, while upper central incisors showed enamel lesions most frequently. The majority of the erosive lesions (48.6%) were found in those with the longest illness period, and 71.7% of the lesions extending into dentine were also found in this group. However, despite suffering from SIV for up to 32 years, 30.3% of the individuals showed no lesions. Conclusions: Dental erosion commonly affects individuals with ED experiencing SIV, and is more often found on the palatal/lingual surfaces than on the buccal in these individuals, confirming a common clinical assumption. Keywords: Dental erosion, Eating disorders, Vomiting Background Eating disorders (ED) are conditions characterized by restricted food intake or binge eating, and often by selfinduced vomiting (SIV). In addition to having the potential to impair both physical health and psychosocial functioning [1], these disorders could also have an impact on oral health. Among oral complications is dental erosion, an irreversible loss of tooth substance as a consequence of exposure to acids that do not involve bacteria [2]. Such acids may enter the oral cavity from extrinsic (e.g. acidic foodstuff ), as well as from intrinsic sources (gastric acid). * Correspondence: m.m.n.uhlen@odont.uio.no Department of Cariology, Institute of Clinical Dentistry, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Oslo, PO Box 1109, Oslo N-0317, Norway The prevalence of ED has been studied in different countries. A nationally representative survey from the U.S. estimated that the lifetime prevalence of ED ranged from 0.6 – 4.5% among adults [3] and from 0.3 – 0.9% among adolescents [4]. According to questionnaire-based, epidemiological studies in Norway, the lifetime prevalence of any ED among adolescents was found to be 12.5% [5], and of anorexia nervosa (AN) and bulimia nervosa (BN) among adult females 0.4% and 1.6%, respectively [6]. A recent study in Finland reported that the lifetime prevalence of AN among young adults was 1.3% and of BN 1.1% [7], whereas a large German study found the prevalence of AN and BN among children and adolescents to be 0.14% and 0.11%, respectively [8]. Significant higher values of erosive tooth wear have been found in patients suffering from ED compared to © 2014 Uhlen et al.; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated. Uhlen et al. BMC Oral Health 2014, 14:92 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6831/14/92 control groups [9-15]. Johansson et al. [15] found that patients with ED had an 8.5-times increased risk of having dental erosion compared to healthy controls, and that individuals with a longer history of ED had lesions more frequently. An obvious risk factor considering dental health in individuals suffering from BN, certain forms of AN or other EDs, is repeated vomiting. The stomach content, which can have a pH close to 1 [16,17], repeatedly reach the mouth and may be destructive to the tooth substance [11]. Recent studies have shown more dental erosive wear among adolescents reporting vomiting [15,18], and that these individuals have a 5.5-times higher risk of dental erosions than those without such behaviour [15]. As emphasized by Hellstrom [19], eating disorders are serious and potentially fatal conditions, where the implications on dental health are reasonably not considered among the most important. However, although many of the physical manifestations of these disorders are reversible, those affecting the teeth’s hard tissue are not [20,21]. Dentists play a significant role in identifying, preventing and treating dental erosion, and it is therefore important to be aware of risk indicators associated with this condition. A common apprehension among clinicians is that dental erosions are typically localized on the palatal surfaces of the upper front teeth in patients with vomiting or regurgitation, while erosions on the buccal or facial surfaces may be a result from high consumption of highly acidic foods and drinks. Although there is some support for this in the literature, [9,10,17,19,22-25], several of these studies have limitations. Three of the studies have a low number of participants included [19,22,24], and calibration of examiners prior to onset of the studies was performed in only one study [23]. In addition, two of the studies did not distinguish between enamel and dentine lesions, making the severity assessment of the erosions difficult [10,25]. This complicates the examiners’ ability to monitor the progression of the lesions. It is often assumed by clinicians and researchers that ED patients have an increased risk of developing dental erosion. However, more information about dental erosions in this risk group is required in order to adequately prevent and treat them. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the occurrence, distribution and severity of dental erosions in patients suffering from eating disorders characterized by self-induced vomiting, and the possible association between dental erosions and the duration of the eating disorder. Methods Participants The individuals included in the study were all undergoing psychiatric and/or medical outpatient treatment at clinics for eating disorders during 2005 – 2013. Because Page 2 of 7 of the assumed relation between eating disorders and dental problems, all patients at these clinics were offered a referral for a dental examination. The patients who were interested were then offered a dental examination at a university dental clinic (University of Oslo, Norway). The eating disorder diagnoses were made by the professional team at the eating disorder clinics. Of 72 referred patients examined at the university dental clinic, 62 had been diagnosed with BN, eight with AN, one with bingeeating disorder (BED) and one with an unspecific eating disorder. Self-induced vomiting was, or had been, a part of the eating disorder for 67 patients, and only these individuals were further studied. After the examination, one additional individual was excluded from the study because of crowns and onlays on all lower molars and upper front teeth. Interview Prior to the dental examination, each patient was interviewed by one examiner. The standardized interview was based on questions from a previously tested questionnaire [26,27], and discussed the patient’s present medical condition, other diseases/diagnoses and medical history. In addition, the examiner asked each patient about their dietary habits, such as consumption of acidic beverages and foods. This consumption was assessed by frequency questions with five possible responses: several times daily, once daily, 3–5 times weekly, 1–2 times weekly and less than once weekly. The participants were also asked if they vomited after eating, and if so, how often (daily, several times weekly, monthly and occasionally) and how long time since the last episode of vomiting. The duration of self-induced vomiting was recorded during the interview, with three possible responses: 3–7 years, 8–10 years and more than 10 years duration of self-induced vomiting. Only a few participants specified the time of last episode of vomiting, and because this ranged from weeks to years, it was therefore not further considered in the study. The frequency of SIV was registered as times of vomiting per week, and ranged from two to 210 times per week. Calibration and clinical examination The intra-oral clinical examination was performed by one previously calibrated clinician (AM). The examiner was calibrated with four other clinicians (intra- and interexaminer agreement values of mean κw = 0.95 and mean κw = 0.73; range 0.71 – 0.76, respectively). For more details see Mulic et al. [28]. The clinical examination was performed in a dental clinic with standard lighting, using mirrors and probes. Access saliva was removed from the teeth with compressed air and cotton rolls. The lingual/palatal and buccal surfaces of all teeth, and the occlusal surface of Uhlen et al. BMC Oral Health 2014, 14:92 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6831/14/92 Page 3 of 7 premolars and molars, were examined. For severity grading of dental erosion, a well established scoring system with the ability to diagnose early stages, as well as more advanced stages of erosion, was required. Scoring of dental erosion was therefore performed according to the Visual Erosion Dental Examination (VEDE) system [27-29]: Score 0: No erosion; score 1: Initial loss of enamel, no dentine exposed; score 2: Pronounced loss of enamel, no dentine exposed; score 3: Exposure of dentine, < 1/3 of the surface involved; score 4: 1/3-2/3 of the dentine exposed; score 5: > 2/3 of dentine exposed. The number and distribution of affected teeth and surfaces were also registered. When surfaces were either filled, repaired with a crown or a veneer, affected by attrition or abrasion, or the tooth had been extracted, the surfaces and teeth were recorded as missing and excluded. Ethical considerations The study was approved by the local Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics and The Norwegian Social Science Data Services. Written, informed consent was obtained from all participants. Statistical analysis The statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA, version 20). Presence of dental erosive wear was used as the dependent variable. Frequency distributions, descriptive and bivariate analyses (Chi-square test) were conducted to provide summary statistics and preliminary assessment of the associations between independent variables and the outcome. The level of significance was set at 5%. Results Participants Of the 66 individuals included, 63 were female and three were male, with a mean age of 27.7 years (range: 20 – 48). Two participants did not answer the question regarding the duration of their eating disorder, but for the remaining 64 participants, the mean duration of the disorder was 10.6 years (range: 3 – 32 years). Prevalence, severity and distribution of dental erosions Of the 66 individuals included in the study, 20 (30.3%) showed no signs of dental erosions. The mean age of these individuals was 27.7 years (range: 20 – 48) and the duration of ED ranged from 3 to 32 years (mean: 10.6). Of the 46 individuals with dental erosion, only 43 answered the question of the duration of SIV. Dental erosions were found in 46 individuals (69.7%), 43 women and three men. Of these, 19 individuals had enamel lesions only, while 27 had both enamel and dentine lesions. Of the individuals with erosions, 35 participants (76.1%) had five or more teeth affected, while 12 (26.1%) had 10 or more teeth with erosive lesions. Four individuals (9%) had ≥10 teeth with dentine lesions. Erosions grade 4 or 5 (severe erosion) were found in only six of the individuals, three of these had been suffering from ED for 16, 21 and 28 years, while two had been diagnosed six and nine years ago. Dentine lesions appeared most frequently on occlusal surfaces (n = 66, 58.4%), followed by palatal surfaces on front teeth (n = 22, 19.5%). Of the 66 surfaces with dentine erosions on occlusal surfaces (Table 1), lower first molars had most often dentine involvement (n = 28), while enamel lesions were most frequently found on upper central incisors (n = 58). Duration of SIV and dental erosions The group of individuals (n = 16) with the longest duration of SIV (>10 years) had 71.7% of the dentine lesions and 40.4% of the enamel lesions (Table 1). Of the individuals included in the study, eight (17.4%) had five or more teeth with dentine lesions. Only seven of these individuals answered the question of the duration of SIV, and for those who did, the mean duration was 17.1 years (range: 6 – 28). Ten participants (21.7%) had Table 1 Distribution and severity of affected tooth surfaces according to duration of SIV Affected tooth surfaces Duration of SIV 3–7 years (n = 14) Duration of SIV 8–10 years (n = 14) Duration of SIV >10 years (n = 16) All individuals (n = 44) E D E+D E D E+D E D E+D E D E+D Front B (n = 79) 21 0 21 26 2 28 Front P (n = 147) 47 2 49 31 4 35 30 0 30 77 2 79 47 16 63 125 22 147 Lateral segments B (n = 15) 0 0 0 0 0 0 11 4 15 11 4 15 Lateral segments P (n = 33) 0 0 0 8 0 8 6 19 25 14 19 33 Lateral segments O (n = 158) 23 15 38 34 9 43 35 42 77 92 66 158 All surfaces 91 17 108 99 15 114 129 81 210 319 113 432 E = Enamel; D = Dentine; Front B = Buccal surfaces of canines and incisors in both upper and lower jaw; Front P = Palatal surfaces of canines and incisors in upper jaw; Lateral segments B = Buccal surfaces of premolars and molars in both upper and lower jaw; Lateral segments P = Palatal surfaces of premolars and molars in upper jaw; Lateral segments O = Occlusal surfaces of premolars and molars in both upper and lower jaw. Uhlen et al. BMC Oral Health 2014, 14:92 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6831/14/92 five or less surfaces with erosions (Figure 1). Seven of the individuals had lesions on occlusal surfaces only. Eight of those with five or less involved tooth surfaces had been suffering from ED for 5 – 10 years, while two patients reported duration of 26 and 28 years, respectively. The distribution of the total number of surfaces with erosive lesions (n = 432) according to the duration of SIV is presented in Table 1. The palatal surfaces were most frequently affected (41.6%), followed by occlusal surfaces (36.6%), regardless of the duration of SIV (Table 1). However, the longer the duration of SIV, the more lesions were recorded on the palatal surfaces of the front teeth and in the lateral segments (Table 1). The same was found on the buccal surfaces; though the prevalence was lower (Table 1). The individuals who had been suffering from ED for more than 10 years had significantly more buccal lesions in the lateral segments than those with a shorter duration of the disorder (p = 0.02). This group did also have significantly more palatal lesions in the lateral segments than those who had been suffering from ED for 3 – 7 years (p < 0.01) and 8 – 10 years (p = 0.04). Nine individuals who had induced vomiting for more than 10 years showed no signs of dental erosions, and in two individuals less than five teeth were affected. Consumption of acidic beverages Of the 54 individuals who answered the questionnaire, 24 reported a high daily intake of acidic beverages (≥0.5 liters per day), 30 participants reported a low consumption (<0.5 liters per day), and of these 17 (70.8%) and 23 persons (76.7%) showed dental erosions, respectively. The mean age in these groups was 28.4 (range: 21 – 48) Page 4 of 7 and 27.5 years (range 20 – 43), and the mean duration of SIV was 12.0 (range: 3 – 28) and 9.9 years (range: 3 – 21). The mean number of teeth with erosions was 4.3 in the high consumption group and 5.8 in the low consumption group. Only one person in the high consumption group showed erosions grade 4 and 5, and no more than 9 teeth were affected, while in the low consumption group 3 individuals showed erosions grade 4 or 5, and six participants had 10 or more teeth affected with dental erosions. Discussion In this study, dental erosions were found in 69.7% of the individuals having a history of self-induced vomiting (SIV). This is in the lower range of previously reported prevalence (47 – 93%) among bulimic patients [11,12,30]. Although all the individuals included in the current study had a history of SIV, and thereby were at risk of developing dental erosions, 30.3% of the participants did not display any signs of erosion lesions. Previous studies have reported different findings. All patients with ED in the study by Robb et al. [10] had significantly more abnormal tooth wear (erosion) than the healthy control group, this finding being most prominent in the SIV group. None of the 23 women with AN in the study by Shaughnessy et al. [31] showed dental erosions, even though 26% of the participants reported a history of binge-eating/purging activity. Rytomaa et al. [11] found that 13 of 35 bulimics did not suffer from dental erosions. The observation that not all bulimic patients show a pathological level of tooth wear has also been reported by Milosevic and Slade [9] and Touyz et al. [30]. Although vomiting has been related to Figure 1 Number of affected surfaces with erosive lesions in relation to duration of SIV. Uhlen et al. BMC Oral Health 2014, 14:92 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6831/14/92 the occurrence of erosive wear, the study by Robb et al. [10] showed that those who suffered from AN, but did not vomit, also showed more erosions than the control population. Dental erosions can be caused by acids from extrinsic (e.g. acidic foodstuff ) as well as from intrinsic sources (gastric acid). In the present study, one of the inclusion criteria was self-induced vomiting, a challenge to the enamel due to exposure to gastric acid. Nearly half (n = 24) of the participants who completed the questionnaire also reported a high daily intake of acidic beverages. It is likely that individuals who induce vomiting up to several times per day have a higher risk of developing dental erosion than those who never, or more seldom, practice this behaviour. It is reasonable to assume that individuals who, in addition to exposing their teeth to gastric acids several times per day, often consume acidic beverages, have a greater risk of developing dental erosion than those who do not. However, in the present study, there were more erosions and more severe lesions in the group with low consumption of acidic beverages than in the group with high consumption. Bartlett and Coward [16] compared the erosive potential of gastric juice and a carbonated beverage in vitro and found that gastric juice had greater potential to cause dental erosions in enamel and dentine than a carbonated drink. The authors pointed out that the result reflects the lower pH and titratable acidity of gastric juice. This could be a reason why more lesions were not found in those individuals who consumed large amounts of acidic beverages in addition to SIV. For patients with ED it is difficult to evaluate the risk of various dietary factors, vomiting and/or unfavourable saliva factors. Information about the frequency and duration of SIV is associated with uncertainties, because ED often are associated with shame and denial. It is often a general finding that these individuals are well-educated and well-informed about the condition. Many of them normally choose healthy diets devoid of sweets and sugary soft drinks. In contrast, when they have episodes of binge-eating they select “junk food”, which is high in fat, sugar, salt and calories [12]. The results from the present study showed that the participants who had been practicing SIV for more than 10 years showed more erosions and more severe lesions (with exposed dentine). Frequent acid exposures may have a detrimental effect on the teeth’s hard tissue, and particularly if the exposures continue over a long period of time. This finding is in accordance with results from Johansson et al. [15] and Altshuler et al. [25], who found a significant association between the duration of the ED and the prevalence of dental erosions. In addition, Dynesen et al. [14] showed that the duration of the ED had a significant influence on the severity grade of the erosive Page 5 of 7 lesions. However, other studies did not find any association between frequency, duration of vomiting and dental erosion [9,10]. In the present study nine individuals who had induced vomiting for more than 10 years showed surprisingly no signs of dental erosions, and in two individuals less than five teeth were affected. The different results from the studies mentioned, and the fact that one third of the individuals in the present study did not show any erosive lesions despite regular vomiting, might be explained by individual differences in the susceptibility to erosion. It is still not clear what factors are relevant for the development and progression of erosion in these patients. Saliva factors, salivary flow rate, the pellicle and the composition of the enamel may be as important as the frequency of acid exposures [10]. It has often been speculated that differences in the composition of saliva could be responsible for the rapidly progressing erosive substance loss in patients with vomiting-associated ED [32]. A lower salivary pH in ED patients than in healthy controls has been documented by Touyz et al. [30], but in contrast Milosevic et al. [33] did not find any differences between BN patients and controls. Schlueter et al. [34] suggested that enhanced proteolytic activity in the saliva of bulimic patients might contribute to an altered buffering capacity of the saliva, as well as development and progression of dental erosion through degradation of dentine and the pellicle. Levels of amylase, immunoglobulin and electrolytes have also been investigated, but the findings differ substantially [32]. Several studies have shown a significantly lower unstimulated salivary flow in bulimic patients than in controls [11,14,19]. Many ED patients are prescribed antidepressants or other psychopharmaceutical medication, that are known to reduce salivary flow, and Dynesen et al. [14] showed that xerogenic medication significantly lowered unstimulated flow rate in this patient group. The assumption that dental erosions caused by vomiting or regurgitations are typically localized on the palatal surfaces of the upper front teeth, and that erosions caused by high consumption of acidic foods and drinks are found on buccal surfaces, has led to efforts to relate the location of erosive lesions to the etiology of the condition [17,22,23]. From a clinical point of view, it is important to investigate whether it is possible to differentiate between erosions caused by SIV and erosions caused by consumption of acidic foodstuff. Hellstrom [19] reported that while lingual erosions were a frequent finding in individuals experiencing SIV, such lesions did not appear in individuals without this behaviour. Lussi et al. [23] found that chronic vomiting appeared to be the variable most indicative for lingual erosions. The present results showed that the majority of the lesions were found on the palatal surfaces and that the individuals with the longest duration of SIV had significantly Uhlen et al. BMC Oral Health 2014, 14:92 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6831/14/92 more buccal and palatal lesions in the lateral segments than those with a shorter duration of the disorder. The more severe lesions (with exposed dentine) appeared most frequently on the occlusal surfaces of the lower first molars, followed by the palatal surfaces on the upper incisors. These results were consistent with work previously reported by Mulic et al. [18] in a study of healthy adolescents, and can partly be explained by the position of these teeth in the mouth and partly by their early time of eruption. The lower first molars are the first permanent teeth to erupt, they have an important function concerning occlusion and chewing, and acidic liquids naturally gravitate towards the floor of the mouth. The upper incisors also erupt at an early age, and as the rough surface of the tongue serves as a short-time reservoir for acids from foodstuff and liquids, the movements of the tongue have the potential to cause both an abrasive and an erosive effect (perimylolysis) on the palatal surface of the upper front teeth [35]. The rinsing effect of saliva is weaker on the upper teeth than on the lower, and the saliva clearance and buffer capacity are even lower in individuals with reduced saliva secretion [17]. Vigorously and frequent tooth brushing is a common habit in ED patients, and in combination with the repeated exposure to stomach acid, this could also contribute to the increased erosive tooth wear in this group [15,19]. However, a study concerning oral hygiene habits did not ascertain why some of the vomiting bulimic patients suffered from severe erosions and others did not [36]. As expected, the prevalence of dental erosion in the individuals experiencing SIV was high. In addition, the duration of SIV seemed to influence the number of palatal and buccal lesions. However, the present study does have some limitations: The proportion of male participants versus females was small. This, however, reflects the gender distribution shown in the study by Jaite et al. [8], where as much as 92.7% of individuals with bulimia nervosa were female, and seems to reflect the population prevalence of ED. Information on e.g. the exact duration of disease, frequency of SIV, oral hygiene habits and eating habits is unfortunately difficult to obtain, as it is based exclusively on the participants’ subjective memory and their willingness to share. One might consider using standardized questionnaires instead of interviews, but these have approximately the same limitations in this matter. Another possible limitation of this study is that the participants were all undergoing treatment at clinics for eating disorders. Thus, the study does not include individuals who do not receive treatment for their disease, and the results might have been different if corresponding information from such individuals was obtained. Saliva secretion was not measured in this study. Considering that one third of the participants with EDs in a study by Rytomaa et al. [11] had decreased unstimulated Page 6 of 7 saliva secretion, and hence decreased protection against dental erosion, this might have been an interesting addition to the study. However, Dynesen et al. [14] found that although individuals with vomiting had a significantly lower unstimulated salivary flow rate compared to a control group, this did not significantly influence dental erosion. Conclusion In the present study, dental erosions frequently affected individuals with ED experiencing SIV, and erosions were more often found on the palatal than on the buccal surfaces in these individuals, supporting a common clinical assumption. However, an interesting finding was that nearly one third of the individuals who had been experiencing SIV presented no visual signs of dental erosion. This emphasizes the necessity of further investigation concerning the etiology of the condition, and of communicating the increasing knowledge of ED and dental erosion to clinical practitioners. Since dentists often are the first health care professionals to whom persons with previously undiagnosed ED may present [32], and as dental care is an important part of the overall treatment for these patients, it is of imperative importance that dentists have an adequate knowledge regarding such disorders and how to prevent and treat the resulting oral consequences. Competing interests The authors declare that they have no competing interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper. Authors’ contributions MMU and AM carried out the data collection; MMU did the data analysis and writing of the article. ABT initiated the idea and along with KRS and AM supervised the project and assisted in writing/editing of the article. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the participants for cooperation during the date collection. Received: 1 April 2014 Accepted: 21 July 2014 Published: 29 July 2014 References 1. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013:329–354. 2. Pindborg J: Pathology of the Dental Hard Tissues. Copenhagen: Munksgaard; 1970:445. 3. Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Kessler RC: The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry 2007, 61(3):348–358. 4. Swanson SA, Crow SJ, Daniel LG, Swendsen J, Merikangas KR: Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in adolescents. Results from the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011, 68(7):714–723. 5. Kjelsas E, Bjornstrom C, Gotestam KG: Prevalence of eating disorders in female and male adolescents (14–15 years). Eat Behav 2004, 5(1):13–25. 6. Gotestam KG, Agras WS: General population-based epidemiological study of eating disorders in Norway. Int J Eat Disord 1995, 18(2):119–126. BMC Oral Health This Provisional PDF corresponds to the article as it appeared upon acceptance. Fully formatted PDF and full text (HTML) versions will be made available soon. Association between harmful alcohol use and periodontal status according to gender and smoking BMC Oral Health 2014, 14:73 doi:10.1186/1472-6831-14-73 Hyang-Sun Kim (lightgoddess@hanmail.net) Ji-Hyun Son (rnldusdns@naver.com) Hee-Yong Yi (frontip@hanmail.net) Hae-Kyoung Hong (pearly705@hanmail.net) Hyoun-Jun Seo (willy0101@naver.com) Kwang-Hak Bae (baekh@snu.ac.kr) ISSN Article type 1472-6831 Research article Submission date 16 April 2014 Acceptance date 17 June 2014 Publication date 20 June 2014 Article URL http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6831/14/73 Like all articles in BMC journals, this peer-reviewed article can be downloaded, printed and distributed freely for any purposes (see copyright notice below). Articles in BMC journals are listed in PubMed and archived at PubMed Central. For information about publishing your research in BMC journals or any BioMed Central journal, go to http://www.biomedcentral.com/info/authors/ © 2014 Kim et al. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated. Association between harmful alcohol use and periodontal status according to gender and smoking Hyang-Sun Kim1,† Email: lightgoddess@hanmail.net Ji-Hyun Son2,† Email: rnldusdns@naver.com Hee-Yong Yi3 Email: frontip@hanmail.net Hae-Kyoung Hong4 Email: pearly705@hanmail.net Hyoun-Jun Seo5 Email: willy0101@naver.com Kwang-Hak Bae3,6,* Email: baekh@snu.ac.kr 1 Department of Physiology, College of Medicine, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea 2 Korean Minjok Leadership Academy, Hoengseong-gun, Wonju, Gangwon-do, Korea 3 Department of Preventive and Public Health Dentistry, School of Dentistry, Seoul National University, 28, Yeongeuon-dong, Jongno-gu, 110-749 Seoul, Republic of Korea 4 Department of Dental Hygiene, Kyungdong University, Wonju, Gangwon-do, Korea 5 Kyoung-ki Academy, Seoul, Korea 6 Dental Research Institute, School of Dentistry, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea † Equal contributors. Abstract Background The aim of this study is to assess the association of harmful alcohol use based on the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT) score with periodontal status according to gender and smoking in a representative sample of Korean adults. Methods This study analyzed 5,291 participants older than 19 years whose data of harmful alcohol use and periodontal status were available. Harmful alcohol use was defined by the WHO guidelines for the administration of AUDIT. The periodontal status was assessed by the Community Periodontal Index (CPI). Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed with adjustment for socio-demographic variables, oral and general health behavior, oral health status and systemic conditions. All analyses considered a complex sampling design, and multivariate analysis was also performed in the subgroups. Results Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed a marginal association between harmful alcohol use and higher CPI in the total sample. The adjusted odds ratio (OR) of harmful alcohol use was 1.16 (0.97 to 1.38) for higher CPI. Higher CPI was significantly associated with harmful alcohol use in men (OR: 1.28; 95% CI: 1.03-1.60) and non-smokers (OR: 1.29; 95% CI: 1.06-1.57). Conclusion Periodontal status is significantly associated with harmful alcohol use in men and nonsmokers in a representative sample of Korean adults. Keywords Harmful Alcohol use, Periodontal status, Association, Gender, Smoking Background Periodontitis is a chronic and long-lasting low-grade inflammatory disease that leads to a break-down of the connective tissue and bone that anchors the teeth to the jaws [1,2]. It is a highly prevalent disease worldwide contributing to the global burden of chronic diseases and represents a major public health problem in many countries [3,4]. In Korea, the prevalence of periodontitis is 29.4% among adults [5]. Periodontitis is also related to systemic alterations such as atherosclerotic vascular disease and metabolic syndrome [6,7]. Long-term and excessive alcohol consumption can influence host defenses causing toxic damage, which is implicated in a wide variety of diseases, disorders, and injuries such as oropharyngeal cancer, liver cirrhosis, pancreatitis, hypertension, gastritis, diabetes, some forms of stroke, and mental disorders such as depression [8-10]. As chronic and even acute, moderate alcohol use can increase host susceptibility to infections caused by bacterial pathogens and impaired host defense after alcohol exposure appears to be linked to a combination of decreased inflammatory response, altered cytokine production, and abnormal reactive oxygen intermediate generation [11], it may be related to periodontitis independently of other potential confounders. However, a recent systematic review reported that, among 14 studies, only 3 studies showed clear association, and 6 studies showed marginal or weak association of alcohol consumption or dependence with periodontitis, while the other 5 studies did not find significant association [10]. Moreover, there was much diversity in the way of measuring alcohol consumption, and most studies considered limited potential confounders or examined non-representative small samples [10,12,13]. Hence, further studies are needed to elucidate whether or not alcohol consumption is a risk factor for periodontitis. The Alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT) was developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) and validated by lots of studies as a simple method of screening for excessive drinking as the cause of the presenting illness, which is the only screening test specifically designed for international use, and in comparison to other screening tests, the AUDIT has been found to perform equally well or at a higher degree of accuracy across a wide variety of criterion measures [14]. When investigating the periodontitis-associated factors, effect modification needs to be considered in an appropriate manner in epidemiological studies because multivariate models with a single estimate require homogeneity of the effect across different levels of extraneous variables such as gender and smoking [15]. However, there are few studies on the association between alcohol consumption based on AUDIT score and periodontitis in a nationally representative sample considering effect modification. Therefore, the aim of this study is to assess the association of harmful alcohol use based on AUDIT score with periodontal status according to gender and smoking in a representative sample of Korean adults. Methods Study design and subject selection The data included a subset of the Fourth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) conducted in 2009 by the Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC). The sampling protocol for the KNHANES was designed to involve a complex, stratified, multistage, probability-cluster survey of a representative sample of the non-institutionalized civilian population in Korea. The survey was performed by the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare. The target population of the survey was all noninstitutionalized civilian Korean individuals aged 1 year or older. The survey employed stratified multistage probability sampling units based on geographic area, gender, and age, which were determined based on the household registries of the 2005 National Census Registry, the most recent 5-year national census in Korea. Using the 2005 census data, 200 primary sampling units (PSU) were selected across Korea. The final sample set for KNHANES included 4,600 households. Among 12,722 sampled individuals, the number of participants was 10,533. The response rate was 82.8%. A total of 7,893 individuals aged over 19 participated in KNHANES, but 5,291 of the participants, who received a periodontal examination, were examined for AUDIT. A detailed description of the sampling was described in the KNHANES report [5]. Clinical variables Periodontal status The WHO community periodontal index (CPI) was used to assess periodontal status. Higher CPI was defined as a CPI greater than or equal to ‘code 3’, which indicates that at least one site had a > 3.5 mm (code 4 > 5.5 mm) – probing pocket depth. The index tooth numbers were 11, 16, 17, 26, 27, 31, 36, 37, 46 and 47. A CPI probe that met the WHO guidelines was used [16]. The mouth was divided into sextants. An approximately 20 g probing force was used. In 2009 KNHANES, 27 trained dentists examined the periodontal status of the subjects. The inter-examiner mean of kappa value was 0.77 (0.53 to 0.94) [17]. Harmful alcohol use The AUDIT was administered as a self-report questionnaire composed of 10 questions including frequency of drinking, typical quantity, frequency of heavy drinking, impaired control over drinking, increased salience of drinking, morning drinking, guilt after drinking, blackouts, alcohol-related injuries, and others concerned about drinking (see Additional file 1: Table S1). Each of the questions has a response with a score ranging from 0 to 4. The participants with a total AUDIT score of 8 or higher were assessed as harmful alcohol use according to the WHO guidelines for the administration of AUDIT [14]. Covariates The socio-demographic variables included gender, age, household income, and educational level. Household income was the family income adjusting for the number of family members. The educational level was assessed by highest diploma. The oral health behaviors included daily frequency of toothbrushing and use of dental floss or interdental brush. As general health behavior, current smoking status was included. According to the current smoking status, the participants were divided to 3 groups (Nonsmokers: those who had never smoked or had smoked fewer than 100 cigarettes in their life, current smokers: those who were currently smoking and had smoked 100 cigarettes or more in their whole life, past smokers: those who had smoked in the past but they stopped smoking at that time). The oral health status included the number of decayed permanent teeth (DT), which was examined and summarized according to WHO criteria [18]. The systemic conditions included diabetes and obesity. Statistical analysis The individual weighted factors were used and the complex sampling design of the survey was considered to obtain the variances. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were applied to examine the relationships between harmful alcohol use and periodontal status. The odds ratios of harmful alcohol use for higher CPI were adjusted for above-mentioned covariates in logistic model. Because the interaction terms of periodontal status with gender and smoking was significant, subgroup analyses were performed to gain estimates stratified according to gender and smoking. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 19.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Results The prevalence of higher CPI defined as a CPI code ≥ 3 was 30.9% (code 4 was 5.9%). The mean age of the participants was 39.13 (38.35 to 39.90) in the participants with lower CPI and 50.30 (49.24 to 51.36) in those with higher CPI. The mean number of DT of the participants was 0.79 (0.71 to 0.86) in the participants with lower CPI and 0.90 (0.79 to 1.01) in those with higher CPI. Table 1 list the characteristics of the study participants categorized by the periodontal status. Table 1 Bivariate comparisons of the characteristics between the participants with lower and higher CPI n Gender (n = 5291) Male Female Highest diploma (n = 5283) Primary school Middle school High school ≥ University or College Household income† (n = 5247) < 25% 25 - 50% 50 - 75% > 75% Diabetes (n = 5291) No Yes Obesity‡ (n = 5251) Underweight Normal Obesity Oral health behaviors Daily frequency of toothbrushing (n = 5291) Once or less Twice Three times or more Use of floss or interdental brush (n = 5291) No Yes General health behaviors Harmful alcohol use§ (n = 5291) No Yes Present smoking status (n = 5282) Past smoker Current smoker Non-smoker Lower CPI %* (95% CI) n Higher CPI %* (95% CI) 1444 63.2 (60.5-65.8) 2176 77.6 (75.3-79.7) 965 706 36.8 (34.2-39.5) 22.4 (20.3-24.7) 666 362 1452 1134 52.0 (47.4-56.5) 58.9 (53.8-63.9) 73.5 (70.7-76.2) 76.4 (73.7-78.9) 497 260 559 353 48.0 (43.5-52.6) 41.1 (36.1-46.2) 26.5 (23.8-29.3) 23.8 (21.1-26.3) 581 786 1036 1182 63.1 (58.5-67.4) 66.6 (63.4-69.7) 69.0 (65.6-72.2) 75.1 (72.4-77.6) 366 424 467 405 36.9 (32.6-41.5) 33.4 (30.3-36.6) 31.0 (27.8-34.4) 24.9 (22.4-27.6) 3450 71.2 (69.1-73.2) 1483 28.8 (26.8-30.9) 170 45.6 (39.4-52.0) 188 54.4 (48.0-60.6) 179 77.8 (71.4-83.1) 55 22.2 (16.9-28.6) 2337 71.6 (69.3-73.8) 1024 28.4 (26.2-30.7) 1068 64.5 (61.4-67.4) 588 35.5 (32.6-38.6) 401 63.2 (58.7-67.6) 1381 66.8 (63.7-69.7) 1838 73.7 (71.3-76.1) 249 738 684 36.8 (32.4-41.3) 33.2 (30.3.-36.3) 26.3 (23.9-28.7) 2653 68.8 (66.4-71.2) 1316 31.2 (28.8-33.6) 967 72.7 (69.5-75.7) 355 27.3 (24.3-30.5) 2519 72.4 (70.0-74.6) 1048 27.6 (25.4-30.0) 1101 65.7 (62.8-68.5) 623 34.3 (31.5-37.2) 662 62.0 (58.5-65.5) 776 61.8 (58.1-65.4) 2213 78.0 (75.7-80.0) 450 515 719 38.0 (34.5-41.5) 38.2 (34.6-41.9) 22.0 (20.0-24.3) * Weighted percent and 95% confidence interval. Household income: monthly average family equivalent income. (=monthly average household income/√(the number of household members)). ‡ Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2); Normal (18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2); obese (≥25 kg/m2). § AUDIT score ≥ 8. † Table 2 showed the marginal association between harmful alcohol use and higher CPI in the multivariate logistic regression model in a total sample. Harmful alcohol use might be associated with higher CPI, but the strength of the association was marginal. The results of the subgroup analyses are also presented in Table 4. The association was different according to the strata of gender and smoking. While harmful alcohol use showed moderate association with higher CPI in males (OR: 1.28; 95% CI: 1.03-1.60) and non-smokers (OR: 1.29; 95% CI: 1.06-1.57), the significant association between harmful alcohol use and higher CPI was not found in females and current smokers. Table 2 Adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of harmful alcohol use (AUDIT score ≥ 8) for higher CPI in total sample and each subgroup Total Gender Male Female Current smoker No Yes OR 1.158 95% CI 0.969-1.383 1.284 0.803 1.028-1.604 0.565-1.139 1.291 1.003 1.058-1.575 0.717-1.403 The multivariate logistic regression model was adjusted for socio-demographic variables (age, gender, household income, educational level), oral health behaviors (daily frequency of toothbrushing, use of floss or interdental brush), general health behaviors (present smoking status), oral health status (active caries) and general health status (diabetes mellitus and obesity). In the subgroup, each effect modifier was excluded from its multivariate model. Discussion In this study, an association was found between harmful alcohol use and periodontal status after adjusting for the socio-demographic variables, oral and general health behaviors, and oral health status, especially in men and non-smokers. While alcohol consumption has been widely perceived as a risk factor of periodontitis due to the biological plausibility based on the relationship between alcohol use and impaired systemic conditions such as reduced resistance to infection and liver damage [19-21], several studies reported a negative correlation between alcohol consumption and periodontitis based on longitudinal and cross-sectional researches. For example, Jansson [22] conducted a longitudinal investigation of 513 individuals from the County of Stockholm in 1970 and 1990. He did not find any significant association between alcohol consumption and periodontitis. Even though the subjects with higher alcohol consumption had calculus more frequently than those with lower alcohol consumption, alcohol consumption was not associated with periodontitis. Torrungruang et al. [23] performed a cross-sectional survey targeting 2,005 people aged 50 to 73 years in Thailand, and also reported that alcohol consumption had no significant effect on the severity of periodontal disease severity in the multivariate model. This disparity might be due to differences in the potential confounders, assessment of alcohol consumption, criteria of periodontitis, and ethnical backgrounds. In addition, effect modification could be another reason for the variation. Most previous studies on the association between alcohol consumption and periodontitis did not consider effect modifiers. Ylöstalo et al. [15] reported that effect modification was not always treated in an appropriate manner in epidemiological studies although it was a basic concept in quantitative research. Based on the analysis of simulation data, they concluded that effect modification might explain the variation in the results of studies on the association between periodontitis and systemic disease. In this study, as we found significant interaction terms, subgroup analysis was performed with subgroups stratified by the levels of effect modifiers. The results of this study did not support the association between harmful alcohol use and periodontal status in the total sample. However, subgroup analysis showed that harmful alcohol use was significantly associated with higher CPI in men and non-smokers. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report gender and smoking as effect modifying factors of the association between alcohol consumption and periodontal status. Some studies reported that smoking and alcohol consumption are associated with increased risk of systemic diseases such as fatty liver disease and metabolic syndrome, especially when these two exposures occur together [24,25]. The result of this study is opposite to those previous results. However, considering that smoking is one of the strongest risk factors for periodontitis [26], it could be inferred that smoking may mask the effect of alcohol consumption on periodontal health in smokers. Briasoulis et al. [27] found that the association between light to moderate alcohol intake and the risk of developing hypertension differed between women and men. They explained that differences in the pattern of drinking, beverage choices, and smoking habits may contribute to the observed sex differences because the health effects of drinking may depend on drinking pattern, and failure to differentiate episodic from regular drinkers may obscure the real associations. It is consistent with the gender difference found in this study. Further studies will be needed to elucidate the association between alcohol consumption and periodontal status according to gender and smoking. The difference in the assessment of alcohol consumption is also suggested to be one of the explanations for the variation in the results of the studies on the association between alcohol consumption and periodontal status. Amaral Cda et al. [10] reported that alcohol consumption was assessed by various unvalidated questionnaires with different criteria varied according to researchers in lots of studies. Therefore, this study used the AUDIT to determine harmful alcohol use. The AUDIT was developed by the WHO and validated by lots of studies as a screening tool for excessive drinking [14]. Epidemiologic studies have used the AUDIT [28,29]. In order to evaluate the AUDIT against other common screening measures, Allen et al. [30] reviewed the studies in which the sensitivity and specificity of the AUDIT were contrasted with those of the alternative measures. They found that the AUDIT performed at a level at least comparable with and generally exceeding that of the alternate measures. However, there have been few studies on the association between periodontitis and alcohol consumption based on AUDIT [31]. This study had several limitations. The periodontal status was assessed by CPI. Although CPI is an easier way to assess the prevalence of periodontitis in a population survey and has been adopted as an index for periodontitis in epidemiologic studies on the association between systemic health and periodontal disease [32], the limitation of CPI should be deliberately considered since it can overestimate or underestimate the prevalence of periodontitis due to the use of representative teeth and pseudo pockets [33]. Therefore, the term of higher CPI was used instead of periodontitis to classify periodontal status. Another important limitation of this study is its cross-sectional design, which makes it impossible to determine the direction of the causal relationship of harmful alcohol use with periodontal status. As the association of subgroups found in this study was so weak, further studies will be needed to confirm the association between harmful alcohol use and periodontal status in men and nonsmokers. Nevertheless, this is the first epidemiologic study to report an effect modification of the association between harmful alcohol use and periodontal status by gender and smoking in a nationally representative sample of adults. Conclusion Periodontal status is significantly associated with harmful alcohol use defined using the AUDIT in men and non-smokers. The underlying mechanisms showing an effect modification of the association between harmful alcohol use and periodontal status by gender and smoking remain to be determined through prospective cohort studies. Human subjects approval statement The study was conducted in compliance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration. Ethical clearance of the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (IRB number. 2009-01CON-03-2C). Competing interests The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Authors’ contributions BK designed the study and, YH and HH performed the statistical analysis. KH, SJ, and SH interpreted the findings and drafted the manuscript. BK read and approved the final manuscript. All authors read and approve the final manuscript. Acknowledgements The study was self-supported, but the Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention provided the data of the Fourth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey to be used in the study. References 1. Li P, He L, Sha YQ, Luan QX: Relationship of metabolic syndrome to chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol 2009, 80:541–549. 2. Williams RC: Periodontal disease. N Engl J Med 1990, 323:373–382. dos Santos Junior et al. BMC Oral Health 2014, 14:47 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6831/14/47 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Early childhood caries and its relationship with perinatal, socioeconomic and nutritional risks: a cross-sectional study Valdeci Elias dos Santos Junior1,2*, Rebeca Maria Brasileiro de Sousa1, Maria Cecília Oliveira1, Arnaldo França de Caldas Junior1 and Aronita Rosenblatt1 Abstract Background: Socioeconomic, perinatal and other life cycle events can be important determinants of the health status of the individual and populations. This study aimed to assess the prevalence of early childhood caries (ECC), perinatal factors (gestational age, teenage pregnancy and birth weight), family income and nutritional risk in children. Methods: A cross-sectional study in which 320 children were examined according to the criteria established by the World Health Organization. A previously validated questionnaire was used to obtain information from parents and guardians about family income, gestational age and birth weight. To check the nutritional risk, we used the criteria provided by the CDC (Center for Disease Control). For Statistics, Pearson’s, chi-square and the multivariate Poisson analyses were used to determine the association among variables. Results: Approximately 20% of children had ECC, and the Poisson multivariate analyses indicated that family income (p = 0.009), birth weight (p < 0.001) and infant obesity (p < 0.001) were related to the increase of ECC, and gestational age was not significantly associated with ECC (p = 0.149). Pregnancy in adolescence was not included in the regression analyses model because it was not statistically significant in the chi-square test (p > 0.05). Conclusion: The prevalence of ECC was related to low family income, premature birth and infant obesity. Keywords: Dental caries, Child, Obesity, Teenage pregnancy, Birth weight, Prematurity Background Early childhood caries is a common public health problem in developing countries, where malnutrition is still an issue. This pattern of decay develops very rapidly in preschoolers, affecting tooth surfaces that are naturally caries-prone [1,2]. Whereas the disease is influenced by social context, this discussion goes beyond the boundaries of oral health issues to social equality [3]. Adverse perinatal factors result in poor oral health conditions, considering that low birth weight children tend to develop enamel and dentine defects, which facilitates the adhesion and colonization of cariogenic bacteria in poorly calcified dental tissue [2,4]. The current literature [3-5] indicates that there is a strong association between enamel defects, prematurity and low birth weight [6]. According to The World Health Organization [7], adolescent pregnancy is a health risk that affects mothers and newborns that also increases disadvantageous social and biological life events [7]. Prematurity and low birth weight is closely related to infant mortality, perinatal infections and the poor growth and development of children [8]. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the prevalence of early childhood caries and its association with perinatal factors, such as gestational age, pregnancy and birth weight, along with family income and nutritional risk, to produce incremental evidence-based knowledge to update the state of care in a fast-growing society. * Correspondence: valdeciodonto@gmail.com 1 Department of Paediatric Dentistry, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Pernambuco, Recife, Brazil 2 Rua São Sebastião, 417 #101 CEP 54410500, Jaboatão dos Guararapes, PE, Brazil © 2014 dos Santos Junior et al.; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated. dos Santos Junior et al. BMC Oral Health 2014, 14:47 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6831/14/47 Methods This is an epidemiological study conducted in Cabo de Santo Agostinho, in the southeastern part of Pernambuco, Brazil, which has a population of approximately 185,123 inhabitants [9]. The sample was comprised of 320 preschoolers aged from three to four years who were attending municipal kindergarten. The calculation of sample size considered that a previous pilot study on ECC indicated a prevalence of 22.3%, with a 95% confidence interval and a 5% standard error. This resulted in a sample of 266 children, and after adding 20% to avoid data loss, a sample size of 320 children was established. The pilot study was conducted with 10% of the sample in the yards of the schools, in a knee-to-knee position, with natural light and using a dental mirror and wooden spatula. Children received oral hygiene instruction and supervised tooth brushing before the exam. The children who took part in this trial were included in the final sampling. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Pernambuco. (Protocol No. 119/12). Consent for undertaking the research was obtained from the school principals, and consent to perform the examinations came from the parents or guardians. Only the children of those parents or guardians who returned the signed permission forms were included in the study. The examinations were performed by a calibrated examiner for visual exam following criteria established by the World Health Organization [10]. Kappa coefficients for intra-examiner agreement was K = 0.90. Cavitated carious lesions in children younger than 71 months were classified as ECC, according by Drury et al. [11]. The individuals with syndromes that impact the oral cavity were excluded from the sample to avoid confounding factors. In addition to the oral examination, children were measured and weighed to assess nutritional risk as proposed by the CDC (Center for Disease Control) [12], which analyses the BMI (Body Mass Index) curve by age and sex from 2–19 years of age. The child was considered to be underweight when the value was below the 5th percentile, normal weight when between the 5th (inclusive) and below the 85th, overweight when between the 85th (inclusive) and 95th and obese when above the 95th percentile. The measurement of body weight was recorded by the researcher, with the child standing with minimal clothing without shoes on a portable calibrated scale with a precision of 100 g, and the height was measured with a tape strip scale. The examiners administered a questionnaire, which was previously validated in a pilot study, to parents and guardians at the pick-up time at school in order Page 2 of 5 to obtain information on family income. To determine the gestational age and birth weight, we accessed the vaccination and the local maternity hospital records that followed the WHO criteria [13], indicating preterm to be less than 37 weeks. The WHO criteria [8] for adolescent pregnancy included girls from 10 to 19 years of age. The classification for birth weight included very low birth weight (less than 1500 g), low birth weight (less than 2500 g) and normal birth weight (equal to or greater than 2500 g). After data collection and the categorization of variables, we created a database for statistical analysis using SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) version 17. To test the association between two categorical variables, the chisquared test was used. To explain the prevalence of early childhood caries and its association with the other risk factors, we chose the Poisson regression test, which is similar to logistic regression, with the advantage that the prevalence ratio (PR) is more stable and the value for OR varies in a smaller range. The margin of error was 5%. Results Three hundred and twenty preschoolers were evaluated. There were no losses or drop-outs because the schools were not very far from each other and we could always return to see those that failed to attend school regularly. The mean age was 43.2 months. The presence of ECC was registered as yes/no and results showed that 20% of children had this type of dental disease. The prevalence of ECC was shown to be related to low family income, low birth weight, infant obesity and shorter gestational age (p < 0.05). There was a higher prevalence of ECC among children with low birth weight (80.4%) than those born with a normal weight (9.9%) and those born preterm (82.8%) compared with those born at term (13.7%) (Table 1). Twenty-five percent (80 cases) involved adolescent pregnancy. Table 2 shows the results for the multivariate Poisson regression analysis to explain the association of early childhood caries with the following variables: family income, birth weight, gestational age and nutritional risk. For significant variables, the probability of the presence of early childhood caries increased if the child was underweight at birth (p < 0.001), demonstrated infant obesity (p < 0.001) or exhibited a family income less than or equal to $ 282.00 (p = 0.009). Pregnancy in adolescence was not included in the statistical regression model because it did not show a statistically significant difference in the person's chi-squared test (p > 0.05). Discussion The present study is in accordance with previous reports [14-16] that describe the strength of the relationship between decreases in family income, the risk of children developing ECC and the impact of this social dos Santos Junior et al. BMC Oral Health 2014, 14:47 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6831/14/47 Page 3 of 5 Table 1 Early childhood caries, family income, adolescent pregnancy, birth weight, gestational age and nutritional risk Evaluation ECC Variable YES NO TOTAL P value PR (IC a 95%) p(1) = 0.01* 3.34 (1.71 to 6.51) N % n % N % 64 20.0 256 80.0 320 100.0 No Income 14 34.1 27 65.9 41 100.0 Less than or equal to minimum wage ($ 282.00) 37 24.3 115 75.7 152 100.0 2.38 (1.32 to 4.27) More than one minimum wage 13 10.2 114 89.8 127 100.0 1,00 Yes 15 18.7 65 81.3 80 100,0 No 38 16 204 84 240 100,0 Low 37 80.4 9 19.6 46 100.0 Normal 27 9.9 247 90.1 274 100,0 Premature 24 82.8 5 17.2 29 100.0 Term 40 13.7 251 86.3 291 100.0 Underweight 2 100,0 - - 2 10,0 Normal weight 57 18.4 253 81.6 310 100.0 Obesity 5 62.5 3 37.5 8 100.0 TOTAL • Family income • Adolescent pregnancy p(1) >0.18 1.16 (0,63 to 2,01) 1,00 • Birth weight p(1) < 0.01* 8.16 (5,55 to 12.00) 1.00 • Gestacional age p(1) < 0.01* 6.02 (4.32 to 8.39) 1.00 • Nutritional Risk p(1) = 0.01* ** (*)Significant association at 5.0%. (**)Unable to determine due to the occurrence of null frequencies. (1) By chi-square test. determinant of health. Lagreca [17] conducted a survey that reported the incidence of dental caries in relation to the socioeconomic status that indicated that in Brazil, children whose family income was in the range of the minimum wage, caries incidence was 57% higher than those whose family income was above four times the minimum wage. Then, with the speed of the production and the diffusion of new and advanced science, it would be anachronistic to continue to refer to the aetiology of dental caries exclusively by the Table 2 Results of multivariate poisson regression to the prevalence of early childhood caries PR and IC 95,0% Variables Univariate Adjusted P value No 3.58 (1.80 a 7.12) 2.42 (1.20 a 4.88) p = 0.009* Less than or equal to minimum wage ($ 282.00) 2.50 (1.36 a 4.61) 2.15 (1,30 a 3.54) 1,00 1,00 8.40 (5.66 a 12.46) 7.09 (3.91 a 12.86) 1,00 1,00 6.11 (4.35 a 8.58) 1.39 (0.89 a 2.19) 1.00 1.00 • Family income More than one minimum wage • Birth weight Low Normal p < 0.001* • Gestational age Premature Term p = 0.149 • Risk nutritional Normal weight Obesity (*):Significant at 5.0%. 1.00 1.00 3,40 (1.89 a 6.11) 6,24 (3.06 a 12.72) p < 0.001* dos Santos Junior et al. BMC Oral Health 2014, 14:47 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6831/14/47 intersection of primary factors, such as microbiota and host substrate. According to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics-IBGE [9], 53.9 million Brazilians live in extreme poverty, which accounts for 31.7% of the population. In the northeastern part of the country, 76.5% of the families earn less than the minimum wage, which is approximately that found in the present study: 60.3% of families living in poverty. From the perspective of health inequality, Marmot, Bell and Goldblatt [18] conceptualized that there is a convergence between unfavourable socioeconomic conditions and the presence of diseases. Corroborating this concept, the present study indicated that children from families that earn less than $ 282 are at a higher risk for ECC. It has been suggested that human life events can alter stable biological mechanisms and turn them into a genetic legacy process called incorporation of biologic features [19]. From this perspective, the traditional etiological factor for caries, which involves the association of high sugar intake [20,21], poor oral hygiene [22-24], lack of exposure to fluoride and perinatal disturbances related to enamel defects [21,24], which could influence genetic legacy. Currently, reports [25,26] show that prematurely born individuals have poor mineralization of the teeth and poorer oral health indicators, supporting the evidence of the role played by enamel defects in the development of ECC. Moreover, in a 7-year cohort study, Targino et al. (2011) [24] revealed that enamel defects constitute a risk factor for the development of early childhood caries. Thus, perinatal factors such as low birth weight and gestational prematurity are risk factors for the development of early childhood caries. Due to the worldwide increase in childhood obesity across populations and the polarization of dental caries, several studies [27,28] reported on the associations of obesity and infant caries; however, the results of these studies are still controversial. In 2006, a systematic review [29] found only one study that consistently showed a direct association between obesity and dental caries with a high level of evidence. The findings of this work show an association between childhood obesity and dental caries, as in some previous epidemiological and cohort studies [27,28]. The results of this study indicate that it is possible that the conflicting results could be related to variations in the way data were collected, the socioeconomic status of the sample, the parameters used to analyse nutritional status and caries diagnosis [29]. Although the present research indicated no significant association between adolescent pregnancy and ECC, perinatal complications arising from the lack of biological development of teenagers are themselves risk factors for Page 4 of 5 preterm and low birth weight children [25], which were identified as risk factors for ECC [29]. Conclusion The prevalence of ECC was shown to be related to low family income, premature birth and infant obesity. Thus, this study showed that socio-economic factors and perinatal events are important determinants for the status of oral health in children. Bullet points It is essential to monitor the prevalence of early childhood caries and its risk factors. Low family income, premature birth and infant obesity should be considered as risk factors for the development of ECC. Competing interest This study was funded by the Ministry of Education of Brazil. Thus, there is no conflict of interest, nor any such interference with the results of this article. Authors’ contributions VSJ participated in the study design and epidemiological data analysis and drafted the manuscript. CMC facilitated the field work and data collection. RMB was the main dentist who examined and diagnosed all of the children. AR and AFCJ were the main supervisors, and they guided the study design, performed statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Acknowledgements The authors would like to express their gratitude to the teachers, school staff and parents who participated in the survey. This study was supported by a grant from the Brazilian Ministry of Education (CAPES). Received: 2 January 2014 Accepted: 1 May 2014 Published: 6 May 2014 References 1. Suckling GW: Development defects of enamel – historical and present day perspectives of their pathogenesis. Adv Dent Res 1989, 3:87–94. 2. Horowitz HS: Research issues in early childhood caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1998, 26(Suppl 1):67–81. 3. Fearne JM, Bryan EM, Elliman AM, Brook AH, Wlliams DM: Enamel defects in the primary dentition of children born weighing less than 2000 g. Br Dent J 1990, 168:433–437. 4. Goodman AH, Martinez C, Chavez A: Nutritional supplementation and the development of linear enamel hypoplasias in children from Tezonteopan. Am J Clin Nutr 1991, 53:773–781. 5. Tesch C, Oliveira BH, Leão A: Measuring the impact of oral health problems on children’s quality of life: conceptual and methodological issues. Cad Saude Publica 2007, 23:2555–2564. 6. Lai PY, Seow WK, Tudehope DI, Rogers Y: Enamel hypoplasia and dental caries in very-low birthweight children: a case-controlled, longitudinal study. Pediatr Dent 1997, 19:42–49. 7. WHO: World Health Organization Health needs of adolescents. Report of a Committee of Experts from WHO. Geneva: WHO; 1997:55p. 8. Guimarães AAG, Velásquez-Meléndez G: Low birth weight determinants from the Born Alive National Surveillance System in Itaúna, Minas Gerais. Rev Bras Saúde Matern Infant 2002, 2:283–290. 9. IBGE: Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. Census 2010; 2013. http://www.censo2010.ibge.gov.br/resultados. 10. WHO: World Health Organization Basic Epidemiological survey of oral health. Manual. 4th edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1997. INSTRUCTIONS Read through the article and answer the multiple choice questions provided at the back of the article. Please note that some questions may have more than one answer; in the case of the latter please “tick” every correct answer. When done only fax through your answer sheet to the fax number given on the answer sheet. QUESTIONNAIRE B3 (14) SELF-INDUCED VOMITING(SIV) AND DENTAL EROSION – A CLINICAL STUDY Question 1: Which of the following are TRUE with regard to dental erosion? A It is a reversible loss of tooth substance B It occurs as a consequence of exposure to acids that do not involve bacteria C It is an irreversible loss of tooth substance D It occurs as a consequence of exposure to acids that involve bacteria E The acids may enter the oral cavity from extrinsic as well as from intrinsic sources Question 2: Is it TRUE or FALSE that significant higher values of erosive tooth wear have been found in patients suffering from eating disorders (ED) compared to control groups? A TRUE B FALSE Question 3: According to recent studies, adolescents reporting vomiting have a how many times higher risk of dental erosions than those without such behavior? A 2 times B 3.5 times C 4 times D 5.5 times E 7 times Question 4: According to this study, what percentage of the individuals having a history of self-induced vomiting was found to have dental erosion? A 47.7% B 53.6% C 69.7% D 93% Question 5: In this study, which group had more erosions and more severe lesions? A In the group with high consumption of acidic beverages B In the group with low consumption of acidic beverages Question 6: Which of the following are characteristic of patients with ED? A ED is often associated with shame and denial B Information about the frequency and duration of SIV is accurate C Patients with ED are generally not well educated and poorly informed about the condition D Many patients with ED choose healthy diets devoid of sweets and sugary soft drinks E When patients with ED have episodes of binge-eating they select “junk food”, which is high in fat, sugar, salt and calories Question 7: Is it TRUE that in all the studies it was found that there was an association between frequency, duration of vomiting and dental erosion? A YES B NO Question 8: Has it been established in several studies that there is a significantly lower unstimulated salivary flow in bulimic patients than in healthy controls? A YES B NO 1 Question 9: The tongue, as a short-time reservoir for acids from foodstuff and liquids, has the potential to cause which of the following on the palatal surface of the upper front teeth? A An abrasive effect B An erosive effect C Both an abrasive and an erosive effect Question 10: Is it TRUE or FALSE that according to Dynesen et al. individuals with vomiting had a significantly lower salivary flow rate compared to a control group and this had a significant influence on dental erosion? A TRUE B FALSE Question 11: Erosions of individuals with ED experiencing SIV, were more often found on which surface? A The palatal surface B Buccal surface C Both the palatal and buccal surfaces had equal erosion ASSOCIATION BETWEEN HARMFUL ALCOHOL USE AND PERIODONTAL STATUS ACCORDING TO GENDER AND SMOKING Question 12: Impaired host defense after alcohol exposure may be linked to which of the following? A Altered cytokine production only B Abnormal reactive oxygen intermediate regeneration C Decreased inflammatory response only D A combination of altered cytokine production, decreased inflammatory response and abnormal reactive oxygen intermediate generation E Periodontitis independently of other potential confounders Question 13: Is it TRUE or FALSE that all the studies, but one, found an association between alcohol use and periodontitis? Question 14: According to some studies smoking and alcohol consumption are associated with increased risk of which of the following systemic diseases? A Fatty liver disease only B Metabolic syndrome only C Fatty liver disease and metabolic syndrome, especially when these two exposures occur together Question 15: Is the AUDIT a validated screening measure to determine harmful alcohol use? A YES B NO A TRUE B FALSE 2 EARLY CHILDHOOD CARIES (ECC) AND ITS RELATIONSHIP WITH PERINATAL, SOCIOECONOMIC AND NUTRITIONAL RISKS Question 16: To which of the following is prematurity and low birth weight closely related? A Poor growth of children B Perinatal infections C Infant mortality D Poor development of children E All of the above Question 17: Is it TRUE or FALSE that low birth weight children tend to develop enamel and dentine defects, which facilitates the adhesion and colonization of cariogenic bacteria in poorly calcified tissue? A TRUE B FALSE Question 18: According to the results of the study which of the following was shown to be related to prevalence of ECC? A High income B Low birth weight C Infant obesity D Low family income E Shorter gestational age Question 19: In Brazil, children whose family income was in the range of the minimum wage, caries incidence was what percentage higher than those whose family income was above four times the minimum wage? A 75% B 5% C 70% D 57% E 50% Question 20: Is it TRUE that the results of several studies reporting on the association of obesity and infant caries are still controversial, and the findings of this study confirm this with no association between childhood obesity and dental caries? A YES B NO 3 PO Box 71 Wierda Park 0149 Tel: 012 653 2394 Fax: 086 614 4200 Cell: 082 566 6910 Website: www.safocus.co.za ANSWER FORM Postal address Professional Board HPCSA No Surname Initials ID Number FOH Number Time spent on activity E-mail Address Fax Number Contact Number Is this for an audit ______Hour ______Min How would you like to receive your IAR? SMS FAX YES NO EMAIL POST B3 (14) SELF-INDUCED VOMITING AND DENTAL EROSION – A CLINICAL STUDY ASSOCIATION BETWEEN HARMFUL ALCOHOL USE AND PERIODONTAL STATUS ACCORDING TO GENDER AND SMOKING EARLY CHILDHOOD CARIES AND ITS RELATIONSHIP WITH PERINATAL, SOCIOECONOMIC AND NUTRITIONAL RISKS A B C D E 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 A B C D E 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 I hereby declare that the completion of this document is my own effort without any assistance. Signed:_________________________________ Date:_____________________ Please rate the article: POOR 1 FAIR 2 AVERAGE 3 GOOD 4 EXCELLENT 5 FAX TO 0866144200 OR 012 653 2073 AFTER COMPLETION This article is accredited for TWO Clinical (2 CEU’s) Mark MODERATED BY: /20 PERCENTAGE % (PASS RATE 70%) PASSED FAILED DATE: 4

© Copyright 2025