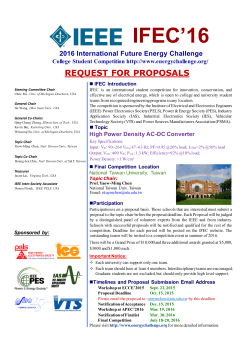

Paper Title: