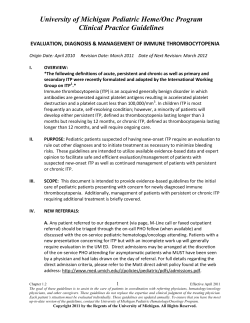

Management of Immune Thrombocytopenic Purpura in Adults Review R S